Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Palabras clave: fungal keratitis, natamycin, voriconazole, Epistemonikos, GRADE.

INTRODUCTION

Infectious keratitis of fungal origin mainly affects people in tropical and subtropical countries, and is an important cause of preventable blindness. Topical antifungals, particularly natamycin and voriconazole, are considered effective, but it is not clear which one is the best treatment alternative.

METHODS

We searched in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others. We extracted data from the systematic reviews, reanalyzed data of primary studies, conducted a meta-analysis and generated a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

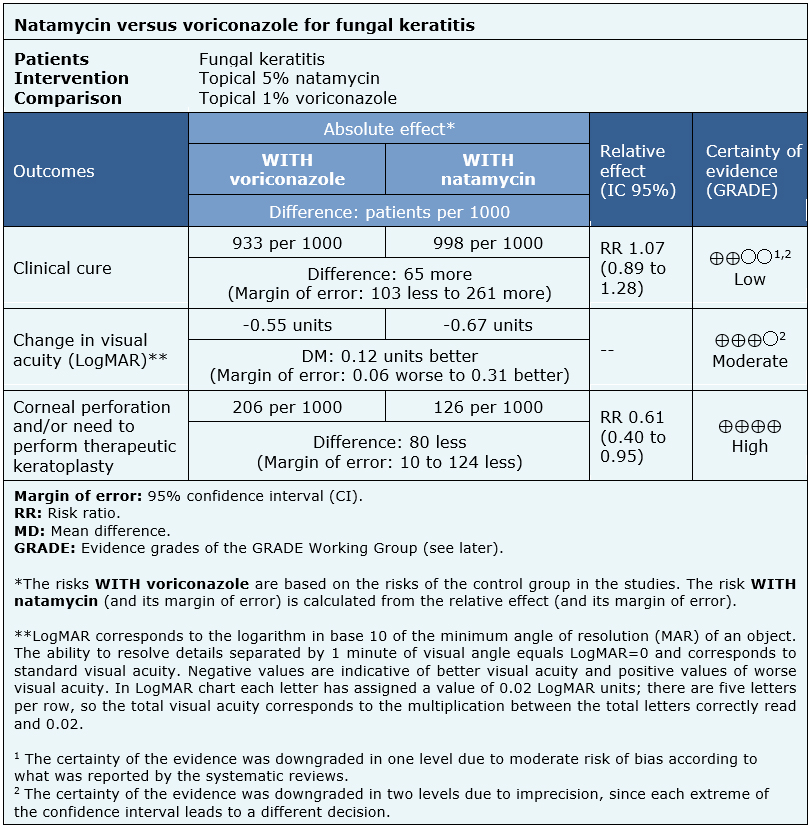

We identified three systematic reviews including three studies overall,all of which were randomized trials. We concluded natamycin probably is associated with better visual acuity after infection, and it prevents corneal perforation and/or need to perform therapeutic keratoplasty compared to voriconazole in fungal keratitis.

Fungal keratitis corresponds to a fungal infection of the cornea, mainly of the epithelium and stroma. The most frequent etiological agents correspond, firstly, to filamentous fungi of the Fusarium, Aspergillus and Curvularia genus, in descending order of frequency and, secondly, to yeasts. In tropical and subtropical countries it constitutes an important cause of preventable blindness, in contrast to what occurs in developed countries, where it scarcely affects the population. The main risk factor corresponds to ocular trauma associated to contamination with plant material, but it has also been associated with the use of corticosteroids, antibiotics, immunosuppressants, chemotherapeutic drugs and ocular prosthetic devices.

There are multiple topical antifungal agents for treatment, such as polyenes (natamycin, amphotericin B), imidazoles (ketoconazole, econazole) and triazoles (fluconazole, posaconazole). The treatment of choice has been for decades topical natamycin, the only antifungal approved by the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA), but the recent emergence of topical voriconazole, a second-generation broad spectrum triazole, has posed new questions, arising thus, the need to evaluate which of these topical antifungals is presented as the best therapeutic alternative.

We searched in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others, to identify systematic reviews and their included primary studies. We extracted data from the identified reviews and reanalyzed data from primary studies included in those reviews. With this information, we generated a structured summary denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos) using a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), meta-analysis of the total of studies when it is possible, a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach and a table of other considerations for decision-making.

|

Key messages

|

|

What is the evidence. |

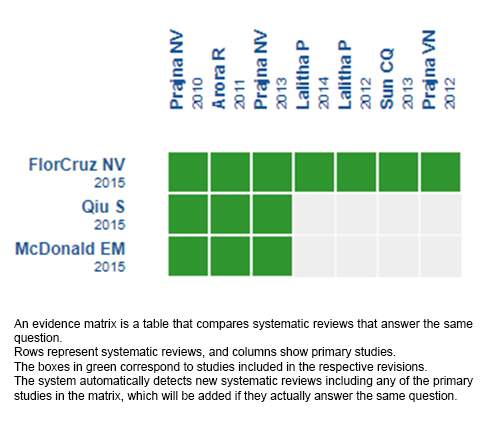

We found three systematic reviews [1], [2], [3] that included three primary studies reported in seven references [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], all corresponding to randomized controlled trials. |

|

What types of patients were included* |

All trials included male and female patients older than 16 years with an average age of 46.7 years, with microbiological evidence of fungal keratitis; direct visualization of hyphae in corneal scraping by smear with 10% KOH stain or Gram stain [5], smear with 10% KOH stain, Giemsa stain or Gram stain [4] and positive corneal ulcer smear for fungi in patients with visual acuity of 20/40 (0.3 logMAR units) at 20/400 (1.3 logMAR units) [8]. All trials excluded patients who had concomitant corneal coinfection (viral, bacterial or protozoal), signs of imminent corneal perforation or history of corneal perforation [4], [5], [8]. Two trials [4], [8] excluded patients with visual acuity worse than 20/200 (1.0 logMAR units) in the unaffected eye and with bilateral ulcers. Two trials excluded patients without light perception in the affected eye [4], [5], and one trial also excluded pregnant patients [4]. |

|

What types of interventions were included* |

All trials used topical 5% natamycin as intervention: two trials administered 1 drop every hour for 1 week and then 1 drop every 2 hours for 2 weeks (while the patient was awake) [4], [8] and one trial 1 drop every hour for 2 weeks [5]. As comparison, topical 1% voriconazole was used: in two trials 1 drop was administered every hour for 1 week and then every 2 hours for 2 weeks (while the patient was awake) [4], [8] and one trial administered 1 drop each hour for 2 weeks [5]. |

|

What types of outcomes |

The trials evaluated multiple outcomes, which were grouped by the systematic reviews as follows:

The average follow-up of the trials was 11.3 weeks, with a range between 10 and 12 weeks. |

* The information about primary studies is extracted from the systematic reviews identified, unless otherwise specified.

The information about the effects of topical 5% natamycin versus topical 1% voriconazole is based on three randomized trials including 473 patients [5], [6], [8].

One trial reported clinical cure (30 patients) [5], three trials reported changes in visual acuity (logMAR) and corneal perforation and/or need to perform therapeutic keratoplasty (434 patients) [5], [6], [8].

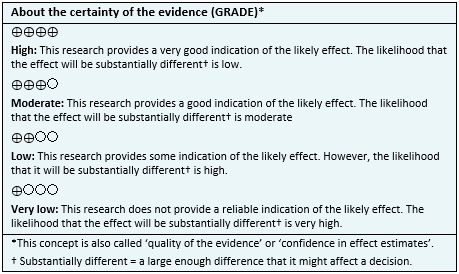

The summary of findings is as follows:

| Follow the link to access the interactive version of this table (Interactive Summary of Findings – iSoF) |

|

To whom this evidence does and does not apply |

|

| About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

| Balance between benefits and risks, and certainty of the evidence |

|

| Resource considerations |

|

| What would patients and their doctors think about this intervention |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

| Could this evidence change in the future? |

|

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Natamycin versus voriconazole for fungal keratitis.

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier.

After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrixes and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

This article is part of the Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis project. It is elaborated with a pre-established methodology, following rigorous methodological standards and internal peer review process. Each of these articles corresponds to a summary, denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos), whose main objective is to synthesize the body of evidence for a specific question, with a friendly format to clinical professionals. Its main resources are based on the evidence matrix of Epistemonikos and analysis of results using GRADE methodology. Further details of the methods for developing this FRISBEE are described here (http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997)

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database (www.epistemonikos.org).

Potential conflicts of interest

The authors do not have relevant interests to declare.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

INTRODUCTION

Infectious keratitis of fungal origin mainly affects people in tropical and subtropical countries, and is an important cause of preventable blindness. Topical antifungals, particularly natamycin and voriconazole, are considered effective, but it is not clear which one is the best treatment alternative.

METHODS

We searched in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others. We extracted data from the systematic reviews, reanalyzed data of primary studies, conducted a meta-analysis and generated a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

We identified three systematic reviews including three studies overall,all of which were randomized trials. We concluded natamycin probably is associated with better visual acuity after infection, and it prevents corneal perforation and/or need to perform therapeutic keratoplasty compared to voriconazole in fungal keratitis.

Autores:

José Retamal[1,2], Gonzalo Ordenes-Cavieres[1,2], Arturo Grau-Diez[2,3]

Autores:

José Retamal[1,2], Gonzalo Ordenes-Cavieres[1,2], Arturo Grau-Diez[2,3]

Citación: Retamal J, Ordenes-Cavieres G, Grau-Diez A. Natamycin versus voriconazole for fungal keratitis. Medwave 2018;18(8):e7387 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2018.08.7387

Fecha de envío: 26/11/2018

Fecha de aceptación: 11/12/2018

Fecha de publicación: 18/12/2018

Origen: Este artículo es producto del Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis Project de la Fundación Epistemonikos, en colaboración con Medwave para su publicación.

Tipo de revisión: Con revisión por pares sin ciego por parte del equipo metodológico del Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis Project.

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

FlorCruz NV, Evans JR. Medical interventions for fungal keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 9;(4):CD004241. | CrossRef | PubMed |

FlorCruz NV, Evans JR. Medical interventions for fungal keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 9;(4):CD004241. | CrossRef | PubMed | Qiu S, Zhao GQ, Lin J, Wang X, Hu LT, Du ZD, Wang Q, Zhu CC. Natamycin in the treatment of fungal keratitis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2015 Jun 18;8(3):597-602. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Qiu S, Zhao GQ, Lin J, Wang X, Hu LT, Du ZD, Wang Q, Zhu CC. Natamycin in the treatment of fungal keratitis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2015 Jun 18;8(3):597-602. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | McDonald EM, Ram FS, Patel DV, McGhee CN. Effectiveness of Topical Antifungal Drugs in the Management of Fungal Keratitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2014 Jan-Feb;3(1):41-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

McDonald EM, Ram FS, Patel DV, McGhee CN. Effectiveness of Topical Antifungal Drugs in the Management of Fungal Keratitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2014 Jan-Feb;3(1):41-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Prajna NV, Mascarenhas J, Krishnan T, Reddy PR, Prajna L, Srinivasan M, Vaitilingam CM, Hong KC, Lee SM, McLeod SD, Zegans ME, Porco TC, Lietman TM, Acharya NR. Comparison of natamycin and voriconazole for the treatment of fungal keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010 Jun;128(6):672-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Prajna NV, Mascarenhas J, Krishnan T, Reddy PR, Prajna L, Srinivasan M, Vaitilingam CM, Hong KC, Lee SM, McLeod SD, Zegans ME, Porco TC, Lietman TM, Acharya NR. Comparison of natamycin and voriconazole for the treatment of fungal keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010 Jun;128(6):672-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Arora R, Gupta D, Goyal J, Kaur R. Voriconazole versus natamycin as primary treatment in fungal corneal ulcers. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011 Jul;39(5):434-40. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Arora R, Gupta D, Goyal J, Kaur R. Voriconazole versus natamycin as primary treatment in fungal corneal ulcers. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011 Jul;39(5):434-40. | CrossRef | PubMed | Prajna VN, Lalitha PS, Mascarenhas J, Krishnan T, Srinivasan M, Vaitilingam CM, Oldenburg CE, Sy A, Keenan JD, Porco TC, Acharya NR, Lietman TM. Natamycin and voriconazole in Fusarium and Aspergillus keratitis: subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012 Nov;96(11):1440-1. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Prajna VN, Lalitha PS, Mascarenhas J, Krishnan T, Srinivasan M, Vaitilingam CM, Oldenburg CE, Sy A, Keenan JD, Porco TC, Acharya NR, Lietman TM. Natamycin and voriconazole in Fusarium and Aspergillus keratitis: subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012 Nov;96(11):1440-1. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Lalitha P, Prajna NV, Oldenburg CE, Srinivasan M, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, Vaitilingam CM, McLeod SD, Zegans ME, Porco TC, Acharya NR, Lietman TM. Organism, minimum inhibitory concentration, and outcome in a fungal corneal ulcer clinical trial. Cornea. 2012 Jun;31(6):662-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Lalitha P, Prajna NV, Oldenburg CE, Srinivasan M, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, Vaitilingam CM, McLeod SD, Zegans ME, Porco TC, Acharya NR, Lietman TM. Organism, minimum inhibitory concentration, and outcome in a fungal corneal ulcer clinical trial. Cornea. 2012 Jun;31(6):662-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, Prajna L, Srinivasan M, Raghavan A, Oldenburg CE, Ray KJ, Zegans ME, McLeod SD, Porco TC, Acharya NR, Lietman TM; Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial Group. The mycotic ulcer treatment trial: a randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazole. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013 Apr;131(4):422-9. | PubMed | PMC |

Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, Prajna L, Srinivasan M, Raghavan A, Oldenburg CE, Ray KJ, Zegans ME, McLeod SD, Porco TC, Acharya NR, Lietman TM; Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial Group. The mycotic ulcer treatment trial: a randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazole. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013 Apr;131(4):422-9. | PubMed | PMC | Sun CQ, Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, Srinivasan M, Raghavan A, O'Brien KS, Ray KJ, McLeod SD, Porco TC, Acharya NR, Lietman TM. Expert prior elicitation and Bayesian analysis of the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial I. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 Jun 14;54(6):4167-73. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Sun CQ, Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, Srinivasan M, Raghavan A, O'Brien KS, Ray KJ, McLeod SD, Porco TC, Acharya NR, Lietman TM. Expert prior elicitation and Bayesian analysis of the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial I. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 Jun 14;54(6):4167-73. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Lalitha P, Sun CQ, Prajna NV, Karpagam R, Geetha M, O'Brien KS, Cevallos V, McLeod SD, Acharya NR, Lietman TM; Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial Group. In vitro susceptibility of filamentous fungal isolates from a corneal ulcer clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Feb;157(2):318-26. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Lalitha P, Sun CQ, Prajna NV, Karpagam R, Geetha M, O'Brien KS, Cevallos V, McLeod SD, Acharya NR, Lietman TM; Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial Group. In vitro susceptibility of filamentous fungal isolates from a corneal ulcer clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Feb;157(2):318-26. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Joseph J., Sharma S. (2016) Antifungal Therapy in Eye Infections: New Drugs, New Trends. In: Basak A., Chakraborty R., Mandal S. (eds) Recent Trends in Antifungal Agents and Antifungal Therapy. Springer, New Delhi. | CrossRef |

Joseph J., Sharma S. (2016) Antifungal Therapy in Eye Infections: New Drugs, New Trends. In: Basak A., Chakraborty R., Mandal S. (eds) Recent Trends in Antifungal Agents and Antifungal Therapy. Springer, New Delhi. | CrossRef | Heralgi MM, Badami A, Vokuda H, Venkatachalam K. An Update On Voriconazole In Ophthalmology. Delhi J Ophthalmol 2016;27;9-15.

Heralgi MM, Badami A, Vokuda H, Venkatachalam K. An Update On Voriconazole In Ophthalmology. Delhi J Ophthalmol 2016;27;9-15.  Sharma S, Das S, Virdi A, Fernandes M, Sahu SK, Kumar Koday N, Ali MH, Garg P, Motukupally SR. Re-appraisal of topical 1% voriconazole and 5% natamycin in the treatment of fungal keratitis in a randomised trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Sep;99(9):1190-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sharma S, Das S, Virdi A, Fernandes M, Sahu SK, Kumar Koday N, Ali MH, Garg P, Motukupally SR. Re-appraisal of topical 1% voriconazole and 5% natamycin in the treatment of fungal keratitis in a randomised trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Sep;99(9):1190-5. | CrossRef | PubMed | World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2004). Guidelines for the management of corneal ulcer at primary, secondary and tertiary care health facilities in the South-East Asia region. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. | Link |

World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2004). Guidelines for the management of corneal ulcer at primary, secondary and tertiary care health facilities in the South-East Asia region. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. | Link | National Health Service (NHS). Joint Ophthalmology and Microbiology Microbial Keratitis Guidelines. 2016 Sept. | Link |

National Health Service (NHS). Joint Ophthalmology and Microbiology Microbial Keratitis Guidelines. 2016 Sept. | Link |