Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

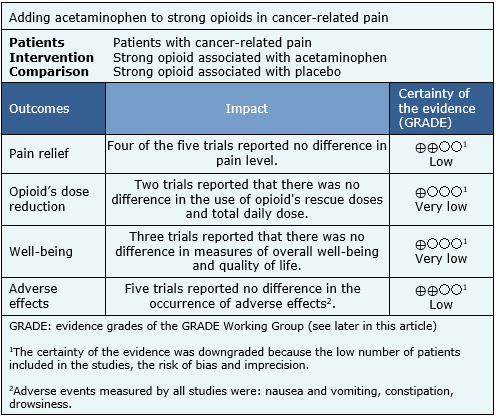

Pain is one of the most frequent and relevant symptoms in cancer patients. The World Health Organization's analgesic ladder proposes the use of strong opioids associated with adjuvants such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in step III. However, it is unclear whether adding acetaminophen to an analgesic regimen based on strong opioids has any benefit in cancer patients with moderate to severe pain. To answer this question we searched in Epistemonikos database, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources. We identified two systematic reviews including five randomized trials overall. We extracted data and generated a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach. We concluded that adding acetaminophen to strong opioids might make little or no difference in improving pain management in cancer patients.

The incidence of cancer has increased worldwide during the last decades. Pain is one of the most frequent complications in cancer patients, especially in advanced stages [1],[2]. In order to address this problem, the World Health Organization (WHO) presented its stepped analgesic strategy in 1986 [3],[4], which has been very effective in improving pain control in cancer patients[5],[6]. The WHO Analgesic Scale recommends that patients who suffer moderate to severe pain (steps II and III) should be managed with an opioid drug and adjuvants, such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

This scheme is justified on the basis of a possible additive or synergistic effect since they have different mechanisms of action: Opioids bind to opioid receptors and replicate the effects of endogenous opioids, inhibiting presynaptic release and the postsynaptic response of excitatory neurotransmitters from nociceptive neurons at different levels of the central and peripheral nervous system. On the other hand, acetaminophen has its analgesic effect through inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis at both the central and peripheral levels, where prostaglandins facilitates pain through the sensitization of nociceptive receptors. Moreover, acetaminophen has other characteristics that makes it easy to prescribe: it is effective for the management of pain of diverse etiologies, it has an excellent safety profile, it is widely available and it is relatively low cost.

However, in cancer patients receiving strong opioids (e.g. morphine or methadone), it is unclear whether adding acetaminophen has any benefit for patients, such as better analgesia, reduction in opioid requirements or decrease in opioid´s adverse effects.

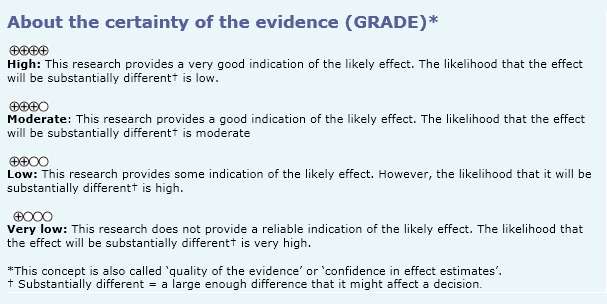

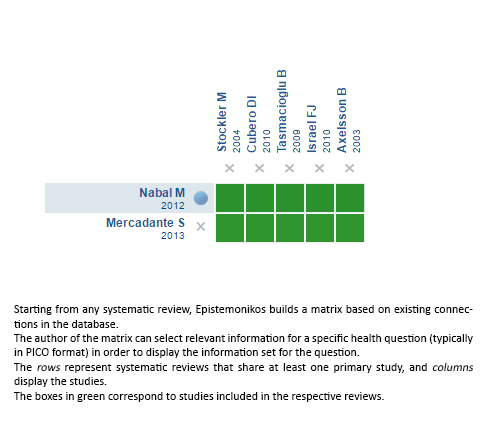

We used Epistemonikos database, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, to identify systematic reviews and their primary studies. With this information we generated a structured summary using a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), a meta-analysis of the total of studies, a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach and a table with other considerations for decision-making.

|

Key messages

|

|

What is the evidence. |

We found two systematic reviews [7],[8] including five randomized controlled trials with a length of follow-up between one and 14 days [9],[10],[11],[12],[13]. |

|

What types of patients were included |

All of the trials included female and male patients, age 18 years or older, with cancer-related pain. The trials included patients with varying degrees of pain: severe pain [9], mild and moderate [10], mild [11] and any intensity [12]; One trial did not specify it [13]. All included patients received a stable dose of a strong opioid, with no modification for at least 48 hours prior to study entry. Three trials accepted patients who were users of adjuvant treatment [10],[12],[13]. The origin of the cancer-related pain was diverse: visceral, somatic, neuropathic. Three trials included patients with solid and hematological cancers [9],[10],[13], one trial only included patients with solid cancer [11] and one trial did not provide this information [12]. Two trials described the presence of metastases in 97% and 100% of included patients [10],[12]. The trials were conducted in outpatients [10],[11],[12], inpatients [9] or both settings [13]. All trials excluded patients with liver disease, contraindications to acetaminophen or who had received radiation therapy within 48 hours prior to study entry. Three trials excluded patients with neuropathic pain [9],[10],[13]. In addition, two trials excluded patients using adjuvants [9],[11]. |

|

What types of interventions were included |

All trials compared the use of a strong opioid associated with acetaminophen versus the same opioid associated with placebo. The included strong opioids were: morphine [9],[11] morphine and hydromorphone [10], methadone [12] and one trial described the use of any strong opioid which dose was equivalent to 200 mg of oral morphine [13]. The dose of acetaminophen was variable: 3 g/day po [12], 4 g/day po [11],[13], 5 g/day po [10] and 4 g/day iv [9]. |

|

What types of outcomes |

Pain intensity was measured through an 11-point verbal scale (from 0 without pain to 10 maximum pain) and also at similar visual scales or facial expression scales. In addition, the trials reported the reduction of total opioid dose, overall well-being scales, patient preference and adverse effects (mainly drowsiness, constipation, nausea and vomiting). |

Problem

The incidence of cancer has increased worldwide during the last decades. Pain is one of the most frequent complications in cancer patients, especially in advanced stages [1], [2]. In order to address this problem, the World Health Organization (WHO) presented its stepped analgesic strategy in 1986 [3], [4], which has been very effective in improving pain control in cancer patients[5], [6]. The WHO Analgesic Scale recommends that patients who suffer moderate to severe pain (steps II and III) should be managed with an opioid drug and adjuvants, such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

This scheme is justified on the basis of a possible additive or synergistic effect since they have different mechanisms of action: Opioids bind to opioid receptors and replicate the effects of endogenous opioids, inhibiting presynaptic release and the postsynaptic response of excitatory neurotransmitters from nociceptive neurons at different levels of the central and peripheral nervous system. On the other hand, acetaminophen has its analgesic effect through inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis at both the central and peripheral levels, where prostaglandins facilitates pain through the sensitization of nociceptive receptors. Moreover, acetaminophen has other characteristics that makes it easy to prescribe: it is effective for the management of pain of diverse etiologies, it has an excellent safety profile, it is widely available and it is relatively low cost.

However, in cancer patients receiving strong opioids (eg, morphine or methadone), it is unclear whether or not adding acetaminophen has any benefit for patients, such as better analgesia, reduction in opioid requirements or decrease in opioid´s adverse effects.

Methods

We used Epistemonikos database, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, to identify systematic reviews and their primary studies. With this information we generated a structured summary using a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), a meta-analysis of the total of studies, a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach and a table with other considerations for decision-making.

Information on the effects of adding acetaminophen to strong opioids in patients with cancer-related pain is based on all of the trials included in this summary, which include 171 patients. All trials measured the reduction of pain with pain scales and the presence of adverse effects. However, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis of these results. The summary of the results is as follows:

|

To whom this evidence does and does not apply |

|

| About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

| Balance between benefits and risks, and certainty of the evidence |

|

| What would patients and their doctors think about this intervention |

|

| Resource considerations |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

| Could this evidence change in the future? |

|

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Addition of acetaminophen to strong opioids for cancer pain

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier. After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrixes and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

The details about the methods used to produce these summaries are described here http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997.

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database (www.epistemonikos.org).

These summaries follow a rigorous process of internal peer review.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have relevant interests to declare.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Pain is one of the most frequent and relevant symptoms in cancer patients. The World Health Organization's analgesic ladder proposes the use of strong opioids associated with adjuvants such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in step III. However, it is unclear whether adding acetaminophen to an analgesic regimen based on strong opioids has any benefit in cancer patients with moderate to severe pain. To answer this question we searched in Epistemonikos database, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources. We identified two systematic reviews including five randomized trials overall. We extracted data and generated a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach. We concluded that adding acetaminophen to strong opioids might make little or no difference in improving pain management in cancer patients.

Autores:

Oscar Corsi[1,2], Pedro E. Pérez-Cruz[1,2,3]

Autores:

Oscar Corsi[1,2], Pedro E. Pérez-Cruz[1,2,3]

Citación: Corsi O, Pérez-Cruz PE. Is it useful to add acetaminophen to high-potency opioids in cancer-related pain?. Medwave2017;17(Suppl2):e6944 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2017.6944

Fecha de envío: 13/4/2017

Fecha de aceptación: 20/4/2017

Fecha de publicación: 4/5/2017

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. High prevalence of pain in patients with cancer in a large population-based study in The Netherlands. Pain. 2007 Dec 5;132(3):312-20 | PubMed |

van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. High prevalence of pain in patients with cancer in a large population-based study in The Netherlands. Pain. 2007 Dec 5;132(3):312-20 | PubMed | Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, de Haes HC, Voest EE, de Graeff A. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007 Jul;34(1):94- | PubMed |

Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, de Haes HC, Voest EE, de Graeff A. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007 Jul;34(1):94- | PubMed | World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1986.

World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1986.  Jadad AR, Browman GP. The WHO analgesic ladder for cancer pain management. Stepping up the quality of its evaluation. JAMA. 1995 Dec 20;274(23):1870-3 | PubMed |

Jadad AR, Browman GP. The WHO analgesic ladder for cancer pain management. Stepping up the quality of its evaluation. JAMA. 1995 Dec 20;274(23):1870-3 | PubMed | Grond S, Zech D, Schug SA, Lynch J, Lehmann KA. Validation of World Health Organization guidelines for cancer pain relief during the last days and hours of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1991 Oct;6(7):411-22 | PubMed |

Grond S, Zech D, Schug SA, Lynch J, Lehmann KA. Validation of World Health Organization guidelines for cancer pain relief during the last days and hours of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1991 Oct;6(7):411-22 | PubMed | Nabal M, Librada S, Redondo MJ, Pigni A, Brunelli C, Caraceni A. The role of paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in addition to WHO Step III opioids in the control of pain in advanced cancer. A systematic review of the literature. Palliat Med. 2012 Jun;26(4):305-12 | CrossRef | PubMed |

Nabal M, Librada S, Redondo MJ, Pigni A, Brunelli C, Caraceni A. The role of paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in addition to WHO Step III opioids in the control of pain in advanced cancer. A systematic review of the literature. Palliat Med. 2012 Jun;26(4):305-12 | CrossRef | PubMed | Mercadante S, Giarratano A. The long and winding road of non steroidal antinflammatory drugs and paracetamol in cancer pain management: a critical review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013 Aug;87(2):140-5 | CrossRef | PubMed |

Mercadante S, Giarratano A. The long and winding road of non steroidal antinflammatory drugs and paracetamol in cancer pain management: a critical review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013 Aug;87(2):140-5 | CrossRef | PubMed | Tasmacioglu B, Aydinli I, Keskinbora K, Pekel AF, Salihoglu T, Sonsuz A. Effect of intravenous administration of paracetamol on morphine consumption in cancer pain control. Support Care Cancer. 2009 Dec;17(12):1475-81 | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tasmacioglu B, Aydinli I, Keskinbora K, Pekel AF, Salihoglu T, Sonsuz A. Effect of intravenous administration of paracetamol on morphine consumption in cancer pain control. Support Care Cancer. 2009 Dec;17(12):1475-81 | CrossRef | PubMed | Stockler M, Vardy J, Pillai A, Warr D. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) improves pain and well-being in people with advanced cancer already receiving a strong opioid regimen: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Aug 15;22(16):3389-94 | PubMed |

Stockler M, Vardy J, Pillai A, Warr D. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) improves pain and well-being in people with advanced cancer already receiving a strong opioid regimen: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Aug 15;22(16):3389-94 | PubMed | Axelsson B, Borup S. Is there an additive analgesic effect of paracetamol at step 3? A double-blind randomized controlled study. Palliat Med. 2003 Dec;17(8):724-5 | PubMed |

Axelsson B, Borup S. Is there an additive analgesic effect of paracetamol at step 3? A double-blind randomized controlled study. Palliat Med. 2003 Dec;17(8):724-5 | PubMed | Cubero DI, del Giglio A. Early switching from morphine to methadone is not improved by acetaminophen in the analgesia of oncologic patients: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Support Care Cancer. 2010 Feb;18(2):235-42 | CrossRef | PubMed |

Cubero DI, del Giglio A. Early switching from morphine to methadone is not improved by acetaminophen in the analgesia of oncologic patients: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Support Care Cancer. 2010 Feb;18(2):235-42 | CrossRef | PubMed | Israel FJ, Parker G, Charles M, Reymond L. Lack of benefit from paracetamol (acetaminophen) for palliative cancer patients requiring high-dose strong opioids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010 Mar;39(3):548-54. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Israel FJ, Parker G, Charles M, Reymond L. Lack of benefit from paracetamol (acetaminophen) for palliative cancer patients requiring high-dose strong opioids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010 Mar;39(3):548-54. | CrossRef | PubMed | Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001 Nov;94(2):149-58. | PubMed |

Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001 Nov;94(2):149-58. | PubMed | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Adult Cancer Pain 2016 [cited July 21, 2016]. | Link |

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Adult Cancer Pain 2016 [cited July 21, 2016]. | Link | Ripamonti CI, Santini D, Maranzano E, Berti M, Roila F; ESMO Guidelines Working Group..Management of cancer pain: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012 Oct;23 Suppl 7:vii139-54 | PubMed |

Ripamonti CI, Santini D, Maranzano E, Berti M, Roila F; ESMO Guidelines Working Group..Management of cancer pain: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012 Oct;23 Suppl 7:vii139-54 | PubMed | Yamaguchi T, Shima Y, Morita T, Hosoya M, Matoba M; Japanese Society of Palliative Medicine. Clinical guideline for pharmacological management of cancer pain: the Japanese Society of Palliative Medicine recommendations. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013 Sep;43(9):896-909 | CrossRef | PubMed |

Yamaguchi T, Shima Y, Morita T, Hosoya M, Matoba M; Japanese Society of Palliative Medicine. Clinical guideline for pharmacological management of cancer pain: the Japanese Society of Palliative Medicine recommendations. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013 Sep;43(9):896-909 | CrossRef | PubMed | Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, Bennett MI, Brunelli C, Cherny N, et al; European Palliative Care Research Collaborative (EPCRC); European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC). Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol. 2012 Feb;13(2):e58-68 | CrossRef | PubMed |

Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, Bennett MI, Brunelli C, Cherny N, et al; European Palliative Care Research Collaborative (EPCRC); European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC). Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol. 2012 Feb;13(2):e58-68 | CrossRef | PubMed |