Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

When three presidential commissions are held in less than five years to address an issue, it means two things: we are facing a real problem, and we have not been able to solve it. This is the case of private health insurance in Chile and its effects on overall health financing. Let us assume that the challenge is to integrate a dimension of equality in the healthcare system and that the whole of society demands health to be recognized as a social right and not a commodity; then the key factor to address these changes is a significant reform of health financing.

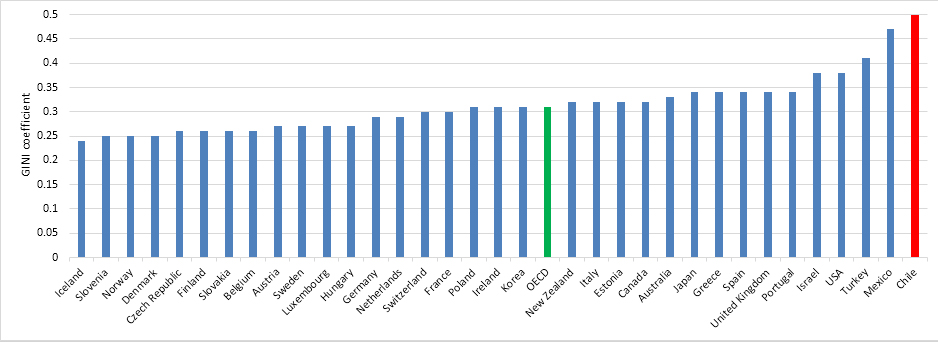

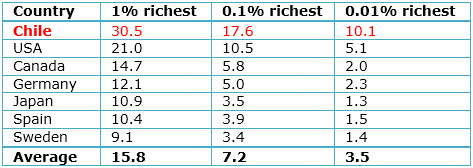

In recent years in Chile, we have repeatedly questioned whether the form of health organization installed after 1980--during Pinochet’s military dictatorship-- in its financing, insurance and delivery dimensions is the most appropriate for a country now ranked as a high-income economy by the World Bank, but also a country plagued by deep inequalities. The grim figures include, among others, a GINI index of 51 (World Bank, 2011), a ranking of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) that places Chile as the country with the worst income inequality (Figure 1) as well as estimates from the University of Chile about the involvement of the super-rich in the total income of the country (Table I).

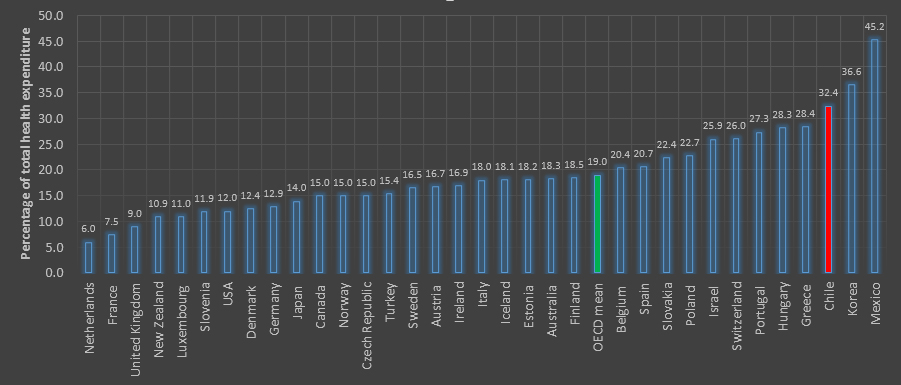

Health indicators do not present a promising picture either. According to the OECD, in 2012 Chile had a total health expenditure of 7.3% of its gross domestic product (GDP), less than half of which is public spending. Out-of-pocket expenditure climbs to 32.4%, among the highest in countries in the organization (Figure 2). Public expenditure was 3.8% of GDP, whereas private spending was 4.1% (OECD, 2010, last available figure), but this 3.8% finances the health needs of 80% of the population. This is why we speak of inequality in healthcare.

These are some of the reasons that led President Michelle Bachelet to convene a third presidential commission this year (the commission is named Cid Commission after the name of its executive secretary). The private health insurance system, besides constituting a problem of inequality in the country, suffers from inherent skimming-the-system-type injustices that have already been addressed in several articles in the Journal [2],[3],[4],[5].

Of the three presidential commissions that have so far completed their reports (Presidential Advisory Committee on Health, 2010; Committee of Experts for the development of a Guaranteed Health Plan in Isapres, 2011; Presidential Advisory Commission for the Study and Proposal for a New Model and Legal Framework for the Private Health System, 2014), the first two were unable to agree on a solution to the problem that motivated the presidential assignment. Likewise, they were not able to propose legal initiatives that could address the issues of constitutionality inherent to discrimination by age and sex, or the system’s unreasonable inequity.

The third commission, the focus of this editorial, did not deliver a consensus report either, but did achieve a strong majority position that set forth guiding principles for future legislation. Whether these principles will translate into structural reforms to healthcare financing in Chile is still to be seen. Deliberations were surrounded by controversy and a contrary offensive fueled by sectors close to the interests of private insurers, whose purpose was to restrict to scope of reforms. However, at the end of the day, the commission responded to the social mandate of changing the current system by providing a long-term vision, and not to limit their proposal to the problems of skimming and discrimination that affects the private health insurance system.

Is it possible to solve the problem of private health insurance without touching public insurance? According to the members of the committee that delivered its final report this October, it would not be possible. They argued that we must move towards building a social security system for the entire population, firmly placing solidarity as a basic social security principle. The committee identified minimum requirements to be met by the potential new system:

- Universality

- Solidarity-based financing

- Broad, universal, and comprehensive benefits, in which primary care is the basis of the care model and not just a gateway to the system

- Mechanisms of purchase that ensure efficiency and health effectiveness

- Open and non-discriminatory affiliation

- Long-term insurance for the entire life cycle

- Community-risk assessments for determining premiums

The task then was to identify how the current legislation can be reformed with a global view on financing, insurance and providers. The response of the commissioners was to propose a vision based on a single fund by the national health insurance plus optional, supplementary, government-regulated private insurance. The proposal includes establishing a unique and universal social security plan, accessible to all inhabitants of the country; and the creation of a universal common fund between the public and private insurance, with the aim of breaking segmentation and introducing solidarity into the system, allowing the financing of universal benefits, and other measures to correct the current system.

But not everyone agrees. Resistance to modify the structural basis of the model of health care in Chile runs very deep; this is also expressed in other areas now being subjected to structural reforms, including education, taxation, the labor code, as well as the Chilean National Constitution itself. Those who prefer the status quo argue that the proposal of the presidential commission will negatively impact everyone: public insurance beneficiaries and to private insurance buyers. They claim that there will be more inequality, less freedom to choose a healthcare provider and, finally, a global impoverishment of the entire system [6]. It is hard to understand the logic behind such conclusions; beyond the natural concern of losing the profits that the current model has gained a few closed financial groups (again, see Table I).

The World Health Organization has stated strongly and repeatedly that the way in which health systems are financed is a critical determinant for achieving universal coverage. Of course, this statement involves the understanding that universal coverage is a public good to promote. Health financing allows health services to exist, to be available, and to be accessible to people whenever there is a need.

Universal health coverage is defined as the right of all individuals to have access to promotion, prevention, curative, rehabilitation and palliative health care services, when they need them; these with a sufficient quality to be effective, and also ensuring that the use of these services does not result in financial hardship for those who use them. To achieve this goal the health system requires to be safe, efficient and well managed; and also to have a system for financing health services; with access to essential medicines and health technologies; and a competent and motivated health workforce, with adequate capacity.

Unfortunately, the fact that the World Health Organization is so determined to promote health as a social right, and continuously strives to deliver to countries concrete proposals on how to assure this right in practice, is the living testimony that countries are not doing it. Not only the poor countries suffer from injustice, and are only brought to the table when news like Ebola outbreaks occur; also, countries with medium or high income ... like Chile, are also constantly and stubbornly pushed to find answers to deeply felt social problems.

The presidential commission that submitted its report in October to President Michelle Bachelet, clearly makes a fundamental contribution to move in the direction of solving the crossroads of social injustice that face Chile at this stage of its human and economic development. It is to be hoped that their proposals are transformed into bills of legislation of short- and long-term range, so that the dedicated work of the commissioners will lead to civil-rights progress for our country.

Interests

The author states that she owns one stock in Isapre Masvida as a physician. Isapre Masvida is a privately owned health insurer owned by over 6,000 physicians, and a Medwave sponsor. The author also declares to be a militant of the Chilean Socialist Party, where she leads a committee on health policy studies.

Vivienne Bachelet can be followed in Twitter: @V_Bachelet

Figure 1. GINI coefficient for countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Source: OECD, 2011.

Figure 1. GINI coefficient for countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Source: OECD, 2011.

Table I. Percentage of country’s Gross National Income for the 1%, 0.1% and 0.01% richest, including capital gains, 2005-2010, Chile compared with other countries. Adapted from López, et al [1].

Table I. Percentage of country’s Gross National Income for the 1%, 0.1% and 0.01% richest, including capital gains, 2005-2010, Chile compared with other countries. Adapted from López, et al [1].

Figure 2. Out-of-pocket expenditure for 2012 (last available figure). Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

Figure 2. Out-of-pocket expenditure for 2012 (last available figure). Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Autora:

Vivienne C. Bachelet[1]

Autora:

Vivienne C. Bachelet[1]

Citación: Bachelet V. The long-term vision of the social security system in health: Chile at the crossroads. Medwave 2014;14(9):e6028 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2014.09.6028

Fecha de publicación: 28/10/2014

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

López RE, Figueroa E, Gutiérrez P. La “parte del león”: nuevas estimaciones de la participación de los súper ricos en el ingreso de Chile. Serie de documentos de Trabajo. Santiago de Chile: Universidad de Chile, Facultad de Economía y Negocios, 2013. | Link |

López RE, Figueroa E, Gutiérrez P. La “parte del león”: nuevas estimaciones de la participación de los súper ricos en el ingreso de Chile. Serie de documentos de Trabajo. Santiago de Chile: Universidad de Chile, Facultad de Economía y Negocios, 2013. | Link | Bachelet VC. Inequality in health – OECD statistics for Chile. Medwave. 2011 Sep;11(09):e5128. | CrossRef |

Bachelet VC. Inequality in health – OECD statistics for Chile. Medwave. 2011 Sep;11(09):e5128. | CrossRef | Cid C. The problems of private health insurance in Chile: Looking for a solution to a history of inefficiency and inequity. Medwave. 2011 Dic;11(12):e5264 | CrossRef |

Cid C. The problems of private health insurance in Chile: Looking for a solution to a history of inefficiency and inequity. Medwave. 2011 Dic;11(12):e5264 | CrossRef | Restovic G. Considerations regarding the proposed Guaranteed Health Plan in Chile. Medwave. 2011 Dic;11(12):e5261 | CrossRef |

Restovic G. Considerations regarding the proposed Guaranteed Health Plan in Chile. Medwave. 2011 Dic;11(12):e5261 | CrossRef | Herrera T. Challenges facing the finance reform of the health system in Chile. Medwave. 2014;14(4):e5958 | CrossRef |

Herrera T. Challenges facing the finance reform of the health system in Chile. Medwave. 2014;14(4):e5958 | CrossRef | Libertad y Desarrollo. Comisión asesora presidencial de salud: misión inadecuada. Santiago de Chile; 9 septiembre 2014. lyd.com [on line] | Link |

Libertad y Desarrollo. Comisión asesora presidencial de salud: misión inadecuada. Santiago de Chile; 9 septiembre 2014. lyd.com [on line] | Link |