Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

In 2013, we wrote about the harm, waste and deception stemming from conducts adopted by the pharmaceutical industry, by concealing raw data and Clinical Study Reports (CSRs) from the regulator’s view when requesting the marketing patent. We described the case of Tamiflu (Roche), a drug that has been widely used in our population and profusely prescribed by physicians. Health authorities, entailing a great cost for the countries in the region, have also purchased it. In this editorial, we will show how the idea of using antivirals for prophylaxis and treatment of influenza took hold, starting from the first enthusiastic recommendations up to the systematic review published last month in the BMJ.

In 2013, we wrote about the harm, waste and deception stemming from conducts adopted by the pharmaceutical industry, by concealing raw data and Clinical Study Reports (CSRs) from the regulator’s view when requesting the marketing patent [1]. We described the case of Tamiflu (Roche), a drug that has been widely used in our population and profusely prescribed by physicians. Health authorities, entailing a great cost for the countries in the region, have also purchased it.

In this editorial, we will show how the idea of using antivirals for prophylaxis and treatment of influenza took hold, starting from the first enthusiastic recommendations up to the systematic review published last month in the BMJ. The review was conducted on individual patient data, as submitted by Roche and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to the research team headed by Tom Jefferson. This systematic review closes the matter by concluding that oseltamivir is of no use for prophylaxis and treatment of influenza [2]. Additionally, we will address the effect this has on the evidence base on which patient-driven decisions are made. We will also refer to the new challenges arising on how systematic reviews are done.

The timeline is eloquent in showing how a therapeutic approach can be imbedded in healthcare practice, even when not founded on sound scientific evidence. After more than ten years of useless expenditure and risk, the recommendation to use neuraminidase inhibitors for prophylaxis (six to eight week cycles), and for treatment of symptomatic seasonal influenza (one week treatments), have been discredited. This story should serve to motivate us to think critically and to promote healthy skepticism, with a view to improving patient care, our guiding principle for medical practice. The financial statements of large pharmaceutical corporations should neither steer nor influence our therapeutic practice.

Tamiflu was developed during the nineties and was authorized by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1999. However, it was not until 2009 when its use became widespread on the heels of the H1N1 pandemic. Collective conviction regarding its alleged effectiveness in reducing the number of days ill from flu –as well as respiratory complications and days spent in hospital– rose to such a level that not prescribing Tamiflu or not taking Tamiflu for prophylaxis was considered almost negligent.

This is a brushstroke of the story, starting from where the now infamous Kaiser study left off [3]: a pooled analysis of ten clinical trials, of which only two had been published, and all financed by Roche. This study was the evidence base –distorted as we now know– for everything that followed.

In 2003, a systematic review was published on the use of oseltamivir and zanamivir [4]. The review concluded that treatment decreased the duration of symptoms from 0.4 to one day in the intention to treat population, and was linked to a relative decrease in the probability of complications with antibiotics from 29 to 43% if administered before the first 48 hours following clinical onset. No evidence of effectiveness was established in terms of major complications requiring hospitalization. In the “prevention” primary outcome for oseltamivir, the systematic review included nine randomized controlled trials, four were included for the “treatment” outcome, and it did not analyze publication bias (when more favorable than non-favorable studies are published), nor did it analyze the funding sources of the included trials. Among the authors is an infectology professor –with strong ties to the pharmaceutical industry, particularly to GlaxoSmithKline (manufacturers of Relenza, Zanamivir) and to Roche (manufacturers of Tamiflu).

Over the following years, a Swedish and another German consensus recommended the neuraminidase inhibitors as first line treatment for influenza [5],[6]. Then on, narrative review articles began to appear mentioning the recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the effectiveness of using these drugs for prophylaxis and treatment [7]. However, the economic analyses were contradictory [8], [9]. Despite the absence of published evidence at the time on the effectiveness of oseltamivir and zanamivir among the elderly as well as children, the recommendation for their use was included in different clinical guidelines and consensus documents in Europe and the United States [10], [11]. Within the context of H5N1 avian flu, some went so far as to say that antivirals would be “highly effective” [12], and thus the debate was pushed towards dosage and drug combinations [13], leaving out questions regarding effectiveness and safety, which were taken for granted.

On June 11, 2009, the World Health Organization issued a level six alert for flu from influenzavirus A subtype H1N1. That same year, a systematic review and economic evaluation on oseltamivir and zanamivir appeared in NICE [14], stating that the former is effective in preventing symptomatic influenza with laboratory confirmation, and particularly among elderly and high-risk groups (RR 0.08; CI 95%: 0.01-0.63). Six studies were included to sustain this conclusion. In terms of household post-exposure prophylaxis, it was also said to be effective (RR 0.19; CI 95%: 0.08-0.45). The study concluded that there was “limited evidence” for determining the effectiveness of this measure in preventing complications, hospitalization, and in shortening clinical duration. No conclusions were drawn regarding cost-effectiveness due to lack of good quality evidence.

Nevertheless, that was the year when major clinical guidelines were issued worldwide stating that oseltamivir should be included in the list of essential drugs. This led many governments to spend astronomical sums to stockpile Tamiflu, a drug whose supply suffered a shortage owing to the veritable mass hysteria triggered after the influenza A pandemic declaration.

Based on a highly questionable expert consensus methodology, the World Health Organization issued their guidelines for pharmacological management of the H1N1 influenza pandemic. Using GRADE criteria (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation), the guidelines stated that for the treatment of patients with suspected or confirmed infection by H1N1 influenza, and severe or progressive clinical presentation, it was recommended that they receive treatment with oseltamivir [15]. This recommendation was rated as strong, with low quality evidence. In light of this recommendation, clinical conduct should be to begin treatment as soon as possible. The guidelines indicated the recommendation should be applied to all patient groups, including pregnant women, children under the age of five, and newborns.

This was a categorical statement coming from the highest global health authority, with which it would be quite unlikely to disagree. More articles were published along those lines [16],[17],[18],[19] and clinical guidelines such as from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and others [20], [21] followed along, to a greater or lesser extent.

Within this context: who would dare contradict what literally the entire world was saying? Well, the Cochrane’s Acute Respiratory Infections Group. In 2006, the first systematic review appeared concluding that “due to its low rate of effectiveness, neuraminidase inhibitors should not be used for managing seasonal influenza, and in times of epidemics or pandemics, they should be associated with other public health measures” [22]. In 2009, these authors concluded that “neuraminidase inhibitors have modest effectiveness against the symptoms of influenza…” [16]. It was this study that triggered a process lasting five years up until the present day, in which this group of researchers led an incredible crusade to obtain the raw data of patients in the Roche trials, both published and unpublished.

What do current or most recent recommendations say?

There continues to be insistence on promptly putting patients on antiviral treatment to reduce morbidity and mortality [23]. Likewise, observational studies suggest that oseltamivir could reduce mortality, as well as hospitalization and symptom duration, more than any other treatment [24]. Until just a few days back, the Chilean Ministry of Health also declared that “antivirals may be used” for influenza, but the webpage where this recommendation was published is no longer available at the time of writing this editorial.

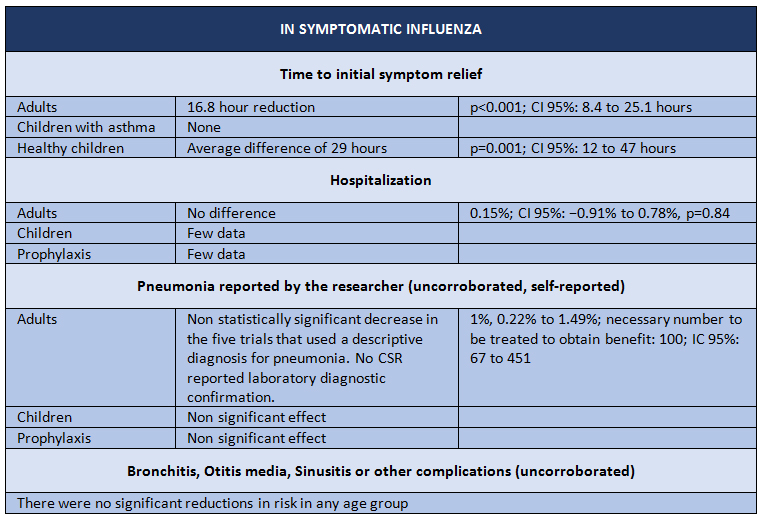

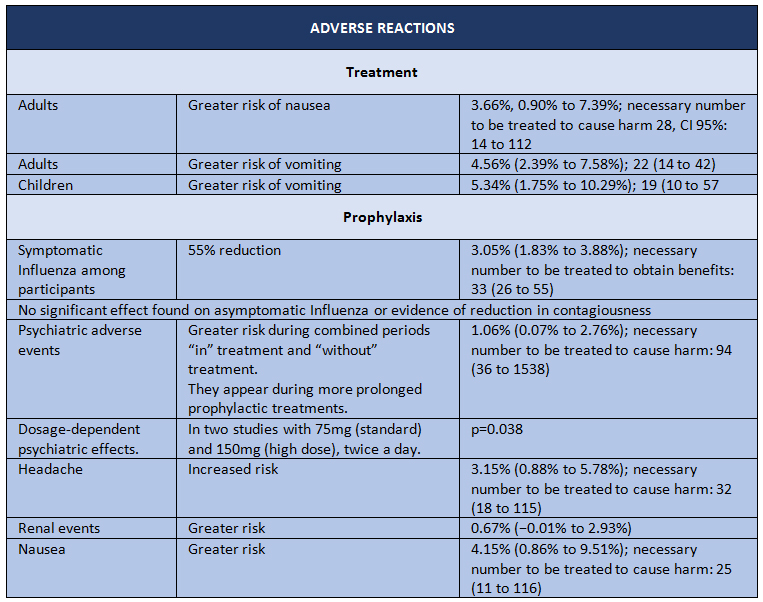

Thus, we come to April 2014, when the last Cochrane review on oseltamivir was published, yet this time based on raw data [2]. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the potential benefits or harms of oseltamivir based on a comprehensive review of all CSRs of randomized clinical trials and regulatory records. The design is a systematic review of regulatory data. The studied outcomes were as follows: time to symptom relief; outcomes pertaining to influenza; complications; hospital admissions; adverse events in the intent to treat population. The data sources consisted of information provided by Roche (after a long public dispute fully disclosed by the BMJ) and EMA, with which the researchers managed to obtain data on 83 clinical trials and more than 150,000 pages. The results are shown in Tables I and II.

The study concludes that oseltamivir reduces the proportion of symptomatic influenza in prophylaxis, but with the downside of a greater risk of psychiatric syndromes, among others. For treatment of symptomatic influenza, oseltamivir produces a modest reduction in time to first alleviation of symptoms, but accompanied by side effects such as nausea, vomiting, as well as renal and psychiatric syndromes.

Why the shift in what was said earlier compared to now? What went wrong along the way?

In the first place, the existence of publication bias. In 2003, when the Kaiser study was published, it referred to ten trials, two published and the rest not. Why weren´t all clinical trials performed by the manufacturer published? The answer is simple: because the manufacturer does not want to, and because it does not suit its interests. The data belongs to the companies that develop the pharmaceutical products, and they conduct the trials. It is legal, and no one can force them to disclose their data, although this is expected to soon change in Europe thanks to the enactment of legislation making compulsory the publication of all results of performed studies. As a result, the published literature does not reflect the research that is actually being done. This is why some people say that there is a 30% overestimation of benefit in industry-funded studies and 80% of harms not being reported.

In the second place, the multisystem failure of the American and European regulatory authorities. Regulators have reached different opinions on safety and efficacy of drugs like Tamiflu. This is because the submitted clinical trials systematically exaggerate efficacy while minimizing risks. Meanwhile, the regulators do not even require that one of the two pivotal studies needed for obtaining a marketing patent be independent. Two important agencies, such as the FDA and the EMA –whose decisions are copied without prior discussion by many other national drug agencies such as those in our own countries– do not communicate with each other, and to make things worse, they even openly disagree on occasion. One cannot ask the pharmaceutical industry to act in the best interests of the public since they are for-profit companies, but we can require this of governments and public agencies.

In the third place, what is known as evidence has changed. The understanding that “The King has no clothes!” resulted in profound self-questioning by the group led by Jefferson on the way in which Cochrane systematic reviews of antivirals for influenza were being done. Is it possible to base conclusions that impact public health decisions on a small group of studies which were funded and conducted by the manufacturers themselves? What lies beneath the tip of the iceberg represented by the published studies? Thus began a relentless process by this group of researchers who after five years have paved the way for this systematic review that is the most open and transparent ever performed. For the first time, there will be access to the raw data on individual patients contained in the CSRs. Twenty non-published trials and 9,623 participants were included. This is the first time the Cochrane Collaboration –in partnership with the BMJ– have performed a review of raw data instead of published articles.

We hope that this story prompts governments and legislators all around the world to reflect on the profound shortcomings of drug safety and efficacy assessment. The case of Tamiflu –wherein its efficacy was overestimated and where reports concerning its harms were left out– is by no means an isolated case. Those who conduct systematic reviews must now revise the methodology and the units of analysis they use, and reconsider what is understood as evidence base. Likewise, those who are involved in institutional and regulatory policy-making that apply to us all will have to begin a process of overhauling the policies that we have had on this issue. The time for reform has come.

Declaration of interests

VCB declares no conflicts of interest with the subject of the article. She states that the Journal has received advertisement funds from some pharmaceutical companies in the last five years.

Table 1. Results of trials with Oseltamivir intervention for symptomatic Influenza. Adapted from Tom Jefferson, et al. [2]

Table 1. Results of trials with Oseltamivir intervention for symptomatic Influenza. Adapted from Tom Jefferson, et al. [2]

Table 2. Adverse reactions in Oseltamivir intervention trials. Adapted from Tom Jefferson, et al. [2]

Table 2. Adverse reactions in Oseltamivir intervention trials. Adapted from Tom Jefferson, et al. [2]

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

In 2013, we wrote about the harm, waste and deception stemming from conducts adopted by the pharmaceutical industry, by concealing raw data and Clinical Study Reports (CSRs) from the regulator’s view when requesting the marketing patent. We described the case of Tamiflu (Roche), a drug that has been widely used in our population and profusely prescribed by physicians. Health authorities, entailing a great cost for the countries in the region, have also purchased it. In this editorial, we will show how the idea of using antivirals for prophylaxis and treatment of influenza took hold, starting from the first enthusiastic recommendations up to the systematic review published last month in the BMJ.

Autora:

Vivienne C. Bachelet[1]

Autora:

Vivienne C. Bachelet[1]

Citación: Bachelet VC. The Tamiflu saga continues: will our conduct change after the publication of the latest systematic review on benefits and harms of oseltamivir?. Medwave 2014;14(4)e:5953 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2014.04.5953

Fecha de publicación: 20/5/2014

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Nombre/name: roberto balassa

Fecha/date: 2014-06-08 22:18:39

Comentario/comment:

Leà su artÃculo con extremo interes pero también leà el artÃculo adjunto que contradice sus afirmaciones en algunos aspectos.

Le agradecerÃa su respuesta y sus comentarios, los cuales definen la conducta clinica a seguir

Atentamente,

Doctor Roberto Balassa

Pediatra

Pediatrics

Today

News

Reference

Education

Dr. R Balassa

Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) > Expert Commentaries

Oseltamivir and Influenza -- The Rush to Judgment

Stephen Y. Liang, MD

DisclosuresMay 23, 2014

1 comment

Print

Email

Editors < Recommendations

When to Give Antiviral Drugs for the Flu

Influenza: Fact or Fallacy?

Is It Influenza?

Topic Alert

Receive an email from Medscape whenever new articles on this topic are available.

Personal Alert Add Influenza to My Topic Alert

Drug & Reference Information

H1N1 Influenza (Swine Flu)

Influenza

Pediatric Influenza

Oseltamivir for Influenza in Adults and Children: Systematic Review of Clinical Study Reports and Summary of Regulatory Comments

Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Spencer EA, Onakpoya I, Heneghan CJ

BMJ. 2014;348:g2545

Study Summary

A recent systematic review by Jefferson and colleagues, conducted for the Cochrane Library and published in the British Medical Journal, takes aim at oseltamivir, one of the most widely stockpiled antiviral agents in our arsenal against seasonal and pandemic influenza. With unprecedented access to full clinical study reports generated from randomized, placebo-controlled trials sponsored by the drug < s manufacturer, Roche, the investigators found that treatment with oseltamivir hastened resolution of symptoms by 16.8 hours in adults but had no effect on rates of hospital admission or diagnostically confirmed pneumonia. Likewise, in children, oseltamivir reduced the time to alleviation of symptoms by 29 hours but had no effect on rates of hospital admission or risk for pneumonia.

Side effects, including nausea and vomiting, were seen more frequently in those who were treated with the drug. When it came to prophylaxis, oseltamivir reduced symptomatic influenza by 55% in participants but had no impact on asymptomatic influenza or interrupting the transmission of disease. Risks for headache as well as psychiatric and renal adverse events were found to be higher in those receiving oseltamivir prophylaxis. In total, 5 deaths were reported in the treatment and prophylaxis trials, all of which were attributed to causes other than influenza. The study authors concluded that although oseltamivir shortened the duration of symptoms, there was no evidence to support the claim that it reduced hospital admissions or serious complications associated with influenza.

Viewpoint

Much of the popular press has taken the message of this systematic review to imply that oseltamivir is no better than acetaminophen when it comes to treating or preventing influenza. The investigators have used their findings to call into question "the stockpiling of oseltamivir, its inclusion on the World Health Organization list of essential drugs, and its use in clinical practice as an anti-influenza drug."

Although many of the benefits of oseltamivir in the otherwise healthy adults and children recruited for the randomized controlled trials underpinning this review may indeed have been overestimated, studies of hospitalized patients paint a somewhat different picture. Treatment with oseltamivir in patients with either seasonal or pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza has demonstrated significant reductions in serious complications leading to intensive care unit admissions and death, optimally when treatment is started within 48 hours of symptom onset. Treatment as far out as 4-5 days after illness onset has been beneficial for some patients.

To this effect, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention continues to recommend[1] the early use of neuraminidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir in the treatment of suspected and confirmed influenza in patients who are hospitalized; those with severe, complicated, or progressive illness; and those at high risk for complications including pneumonia and respiratory failure.

The systematic review published by Jefferson and colleagues is a remarkable accomplishment not only in terms of its groundbreaking methodology but the championing of a higher level of transparency in the conduct and reporting of data from clinical trials, particularly those sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry. However, caution must be taken in generalizing their results to all influenza patients, particularly those who are severely ill and hospitalized, especially during pandemics. Although oseltamivir < s true role in treating influenza in these patients under such circumstances has yet to be clarified through a randomized controlled trial, to say that this agent has little or no role is likely premature.

References

1 comment

Comment

Post as:

Commenting is moderated. See our Terms of Use.

Latest in Infectious Diseases

Mosquito-Borne Chikungunya Virus Spreads in the Americas

Many Lyme Tests Unnecessary, Experts Say

Saudi MERS Data Review Shows Big Jump in Number of Deaths

Uptick in Worldwide Polio Cases in 2013 Continues Into 2014

Ultraviolet Disinfection Cuts Hospital-Acquired Infections

© 2014 WebMD, LLC

Cite this article: Stephen Y. Liang. Oseltamivir and Influenza -- The Rush to Judgment. Medscape. May 23, 2014.

advertisement

Most Popular Articles

According to PEDIATRICIANS

Hypoxia in Preemies: How Long Should Caffeine Be Used?

The Pediatrician < s Pay: A Slow Climb Toward Equity

Impact of Poor Sleep Equal to Binge Drinking, Marijuana Use

Early Repetitive Behaviors Reliably Predict Autism

Guidelines Could Lead to Missed Urine Reflux in Kids

View More

More from your Pediatrics MedPulse newsletter...

FeaturesThe Inevitable Loss

First Confirmed Cases of MERS-CoV Infection in the US

Oseltamivir and Influenza -- The Rush to Judgment

Surgical Innovations in Pediatric Ophthalmology

Infant Assessment and Reduction of Postnatal Collapse Risk

Top StoriesAssessing Recovery From Concussion

Hypoxia in Preemies: How Long Should Caffeine Be Used?

Doctors Are Talking: EHRs Destroy the Patient Encounter

An Infant in Acute Respiratory Distress: Case Challenge

Surgery for Children With Crohn < s Disease

Patient Contact: Shake Hands, Hug, Fist Bump, or Just Smile?

About Medscape

Privacy Policy

Terms of Use

WebMD

MedicineNet

eMedicineHealth

RxList

WebMD Corporate

Help

All material on this website is protected by copyright, Copyright © 1994-2014 by WebMD LLC. This website also contains material copyrighted by 3rd parties.

Nombre/name: Vivienne Bachelet

Fecha/date: 2014-06-09 11:14:24

Comentario/comment:

Muchas gracias por su comentario.

Me parece entender que pide que comente sobre el resumen del estudio, pero no me queda claro dónde se publicó este resumen. ¿Fue en el BMJ? Intenté acceder a un comentario en Medscape pero me pide contraseña, por lo que no me quedó clara su referencia.

En todo caso, cuando yo afirmo que no sirve Tamiflu es porque hay que sopesar los daños con los beneficios, tal como indico en el editorial. La revisión sistemática de Jefferson et al concluye que el beneficio es acortamiento de menos de 1 dÃa (en condiciones controladas, e indicado al inicio del cuadro), en influenza sintomática. Entonces, hay que poner sobre la balanza la mayor tasa de efectos secundarios que no se habÃan reportado anteriormente y que ahora aparecen reportados. Además, es necesario considerar el costo del medicamento. Estas últimas consideraciones aplican sobre todo en uso profiláctico de los antivirales.

Entonces, ¿vale la pena indicar Tamiflu si el beneficio no es el que se habÃa señalado cuando se recomendó a los gobiernos tener stock de oseltamivir e indicar como profilaxis? Lo que se habÃa dicho entonces es que Tamiflu reducÃa la frecuencia de hospitalizaciones y complicaciones secundarias, pero ahora, con esta última revisión sistemática realizada sobre los datos brutos de los ensayos clÃnicos, eso no se ha visto corroborado.

En el siguiente link figura quizás la opinión que usted considera contradictoria con mi editorial: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/821653. Pero es muy importante revisar las fechas de publicación. El comentario de Angela Campbell en el sitio de Medscape (que debemos recordar no es una revista biomédica revisada por pares) aparece el 17 de marzo, por lo que se basa en la información previamente existente sobre antivirales en influenza que, como sabemos, adolecÃa de fuerte sesgo de publicación. La revisión sistemática de Jefferson se publicó en el BMJ el 10 de abril de 2014. En Medwave consideramos de suma importancia esta revisión sistemática por lo que publicamos el editorial.

Nuevamente, gracias por expresar su opinión en la Revista.

Nombre/name: RAUL ERNESTO VARGAS

Fecha/date: 2014-11-09 18:11:10

Comentario/comment:

Excelente artÃculo Dra.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Bachelet V. A tale of harm, waste and deception: how big pharma has undermined public faith in trial data disclosure and what we can do about it. Medwave. 2013;13(4):e5671. | CrossRef |

Bachelet V. A tale of harm, waste and deception: how big pharma has undermined public faith in trial data disclosure and what we can do about it. Medwave. 2013;13(4):e5671. | CrossRef | Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Spencer EA, Onakpoya I, Heneghan CJ. Oseltamivir for influenza in adults and children: systematic review of clinical study reports and summary of regulatory comments. BMJ. 2014;348:g2545. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Spencer EA, Onakpoya I, Heneghan CJ. Oseltamivir for influenza in adults and children: systematic review of clinical study reports and summary of regulatory comments. BMJ. 2014;348:g2545. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kaiser L, Wat C, Mills T, Mahoney P, Ward P, Hayden F. Impact of oseltamivir treatment on influenza-related lower respiratory tract complications and hospitalizations. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(14):1667-72. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kaiser L, Wat C, Mills T, Mahoney P, Ward P, Hayden F. Impact of oseltamivir treatment on influenza-related lower respiratory tract complications and hospitalizations. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(14):1667-72. | CrossRef | PubMed | Cooper NJ1, Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Wailoo A, Turner D, Nicholson KG. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in treatment and prevention of influenza A and B: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2003;326(7401):1235. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Cooper NJ1, Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Wailoo A, Turner D, Nicholson KG. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in treatment and prevention of influenza A and B: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2003;326(7401):1235. | CrossRef | PubMed | Uhnoo I, Linde A, Pauksens K, Lindberg A, Eriksson M, Norrby R. Treatment and prevention of influenza: Swedish recommendations. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35(1):3–11. | PubMed |

Uhnoo I, Linde A, Pauksens K, Lindberg A, Eriksson M, Norrby R. Treatment and prevention of influenza: Swedish recommendations. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35(1):3–11. | PubMed | Wutzler P, Kossow K-D, Lode H, Ruf BR, Scholz H, Vogel GE. Antiviral treatment and prophylaxis of influenza in primary care: German recommendations. J Clin Virol. 2004;31(2):84–91. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wutzler P, Kossow K-D, Lode H, Ruf BR, Scholz H, Vogel GE. Antiviral treatment and prophylaxis of influenza in primary care: German recommendations. J Clin Virol. 2004;31(2):84–91. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kirkbride HA, Watson J. Review of the use of neuraminidase inhibitors for prophylaxis of influenza. Commun Dis Public Health. 2003;6(2):123–7. | PubMed |

Kirkbride HA, Watson J. Review of the use of neuraminidase inhibitors for prophylaxis of influenza. Commun Dis Public Health. 2003;6(2):123–7. | PubMed | Schmidt AC. Antiviral therapy for influenza : a clinical and economic comparative review. Drugs. 2004;64(18):2031–46. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Schmidt AC. Antiviral therapy for influenza : a clinical and economic comparative review. Drugs. 2004;64(18):2031–46. | CrossRef | PubMed | Reisinger K, Greene G, Aultman R, Sander B, Gyldmark M. Effect of influenza treatment with oseltamivir on health outcome and costs in otherwise healthy children. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24(7):395–407. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Reisinger K, Greene G, Aultman R, Sander B, Gyldmark M. Effect of influenza treatment with oseltamivir on health outcome and costs in otherwise healthy children. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24(7):395–407. | CrossRef | PubMed | Cools HJM, van Essen GA. Practice guideline “Influenza prevention in nursing homes and care homes”, issued by the Dutch Society of Nursing Home Specialists; division of tasks between nursing home specialist, general practitioner and company doctor. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2005;149(3):119–24; discussion 116–8. | PubMed |

Cools HJM, van Essen GA. Practice guideline “Influenza prevention in nursing homes and care homes”, issued by the Dutch Society of Nursing Home Specialists; division of tasks between nursing home specialist, general practitioner and company doctor. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2005;149(3):119–24; discussion 116–8. | PubMed | Lynch JP, Walsh EE. Influenza: evolving strategies in treatment and prevention. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28(2):144–58. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Lynch JP, Walsh EE. Influenza: evolving strategies in treatment and prevention. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28(2):144–58. | CrossRef | PubMed | Moscona A. Medical management of influenza infection. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:397–413. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Moscona A. Medical management of influenza infection. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:397–413. | CrossRef | PubMed | White NJ, Webster RG, Govorkova EA, Uyeki TM. What is the optimal therapy for patients with H5N1 influenza? PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000091. | CrossRef | PubMed |

White NJ, Webster RG, Govorkova EA, Uyeki TM. What is the optimal therapy for patients with H5N1 influenza? PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000091. | CrossRef | PubMed | Tappenden P, Jackson R, Cooper K, Rees A, Simpson E, Read R, et al. Amantadine, oseltamivir and zanamivir for the prophylaxis of influenza (including a review of existing guidance no. 67): a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(11):iii, ix–xii, 1–246. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tappenden P, Jackson R, Cooper K, Rees A, Simpson E, Read R, et al. Amantadine, oseltamivir and zanamivir for the prophylaxis of influenza (including a review of existing guidance no. 67): a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(11):iii, ix–xii, 1–246. | CrossRef | PubMed | WHO guidelines for pharmacological management of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza and other influenza viruses. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO), 2009:83. [on line] | Link |

WHO guidelines for pharmacological management of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza and other influenza viruses. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO), 2009:83. [on line] | Link | Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Del Mar C. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b5106. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Del Mar C. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b5106. | CrossRef | PubMed | Smith JR, Ariano RE, Toovey S. The use of antiviral agents for the management of severe influenza. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):e43–51. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Smith JR, Ariano RE, Toovey S. The use of antiviral agents for the management of severe influenza. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):e43–51. | CrossRef | PubMed | Reddy D. Responding to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza: the role of oseltamivir.J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(Suppl 2):ii35–ii40. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Reddy D. Responding to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza: the role of oseltamivir.J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(Suppl 2):ii35–ii40. | CrossRef | PubMed | Smith JR, Rayner CR, Donner B, Wollenhaupt M, Klumpp K, Dutkowski R. Oseltamivir in seasonal, pandemic, and avian influenza: a comprehensive review of 10-years clinical experience. Adv Ther. 2011;28(11):927–59. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Smith JR, Rayner CR, Donner B, Wollenhaupt M, Klumpp K, Dutkowski R. Oseltamivir in seasonal, pandemic, and avian influenza: a comprehensive review of 10-years clinical experience. Adv Ther. 2011;28(11):927–59. | CrossRef | PubMed | Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D, Gubareva L, Bresee JS, Uyeki TM. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza --- recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(1):1–24. | PubMed | Link |

Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D, Gubareva L, Bresee JS, Uyeki TM. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza --- recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(1):1–24. | PubMed | Link | Rodríguez A, Alvarez-Rocha L, Sirvent JM, Zaragoza R, Nieto M, Arenzana A, et al. Recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Work Group (GTEI) of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC) and the Infections in Critically Ill Patients Study Group (GEIPC) of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) for the diagnosis and treatment of influenza A/H1N1 in seriously ill adults admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. Med Intensiva. 2012;36(2):103–37. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Rodríguez A, Alvarez-Rocha L, Sirvent JM, Zaragoza R, Nieto M, Arenzana A, et al. Recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Work Group (GTEI) of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC) and the Infections in Critically Ill Patients Study Group (GEIPC) of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) for the diagnosis and treatment of influenza A/H1N1 in seriously ill adults admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. Med Intensiva. 2012;36(2):103–37. | CrossRef | PubMed | Jefferson TO, Demicheli V, Di Pietrantonj C, Jones M, Rivetti D. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD001265. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Jefferson TO, Demicheli V, Di Pietrantonj C, Jones M, Rivetti D. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD001265. | CrossRef | PubMed | Committee on infectious diseases. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2013-2014. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):e1089–104. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Committee on infectious diseases. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2013-2014. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):e1089–104. | CrossRef | PubMed | Santesso N, Hsu J, Mustafa R, Brozek J, Chen YL, Hopkins JP, et al. Antivirals for influenza: a summary of a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2013;7 Suppl 2:76–81. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Santesso N, Hsu J, Mustafa R, Brozek J, Chen YL, Hopkins JP, et al. Antivirals for influenza: a summary of a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2013;7 Suppl 2:76–81. | CrossRef | PubMed | Una historia de perjuicio, desperdicio y engaño: cómo la gran industria farmacéutica ha socavado la fe pública en los datos de sus ensayos clínicos y qué podemos hacer al respecto

Una historia de perjuicio, desperdicio y engaño: cómo la gran industria farmacéutica ha socavado la fe pública en los datos de sus ensayos clínicos y qué podemos hacer al respecto