Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Palabras clave: adolescent behavior, suicide, adolescent health

Introduction

Adolescence is one of the stages in life most affected by suicide. In Peru, 22% of suicides occur in people 10 to 19 years old. However, mental health overall and factors associated with suicidal behaviors have not been well studied.

Objective

To determine the prevalence of suicidal behaviors (ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning) and associated factors in Peruvian adolescent students.

Methods

A cross-sectional study analyzing data from the Global School-based Student Health Survey for Peru in 2010 was conducted to measure the prevalence of suicidal behaviors (ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning) and associated factors in Peruvian adolescent students.

Results

Of the 2521 students evaluated, 19.9% (95% CI: 17.8 to 22.2) presented suicidal ideation and 12.7% (95% CI: 11.1 to 14.5) presented suicidal planning in the last 12 months. Females had a higher prevalence of both ideation (27.5%, 95% CI: 24.9 to 30.4) and ideation plus suicidal planning (18.5%, 95% CI: 16.4 to 20.7). Multivariate analysis found that being female, having little parental support, having felt loneliness, having suffered from physical aggression, having been bullied, and alcohol consumption, were associated with ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning in adolescent students.

Conclusion

Ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning is a problem in the Peruvian adolescent population and is associated with several factors. Strategies are needed to identify and register suicide in adolescents in Peru and to develop prevention programs.

|

Key ideas

|

Suicide is a global public health problem that generates a high economic, social, and psychological burden. In 2012, about 800 000 deaths worldwide were reported as suicides; in terms of standardized mortality, this translates to 11.4 per 100 000 people (15.0 in men and 8.0 in women), making suicide the 15th leading cause of death, comprising 56% of all violent deaths and 1.4% of all deaths worldwide[1]. The actual number of deaths from suicide may be even higher, as sensitivity regarding the subject of suicide in various cultures can lead to under-reporting[1]. To help address the problem, during the 66th World Health Assembly in 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the WHO Mental Health Action Plan 2013 to 2020, which aims to reduce the suicide rate by 10% among all member states by 2020[2].

Suicide from self-inflicted injuries in the adolescent population is one of the most significant health problems in this age group worldwide, causing 6% of adolescent deaths and a high number of potential years of life lost[3]. In 2012, suicide was the second leading cause of death in people 15 to 29 years old, causing 8.5% of total deaths, with higher prevalence in males[1]. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), prevalence of suicidal ideation (thinking about committing suicide, common in adolescents) and suicidal planning (formulating a specific method for suicide) is 16.9% and 17.0% respectively[4] and is associated with traumatic experiences, attempted suicide, and suicide[1],[5],[6].

For the period January 2017 to June 2018, Peru’s National Institute of Mental Health reported 64 cases of attempted suicide in children 8 to 17 years old, a higher number of cases than in previous years[7]. A previous study of mortality data by the Ministry of Health of Peru (MINSA) found that 22% of suicides in the period 2004-2013 occurred in young people 10 to 19 years old[8]. While MINSA has collected information on mental health in Peruvian schoolchildren, to date, only descriptive information about suicidal behaviors has been reported[8]; factors associated with suicidal behavior in Peruvian adolescents (including ideation and planning) have not been described. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning and associated factors in Peruvian adolescent students.

Design and scope

An analytical cross-sectional study of the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) was carried out in Peru by MINSA in coordination with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Data sources

The GSHS is a national survey administered to public school students in the second, third, and fourth years of secondary education. The most recent survey was carried out between November and December 2010. To obtain a representative sample of second-, third-, and fourth-grade students in public high schools in Peru, the GSHS 2010 used a two-stage sampling method (first stage: identification of all schools with second, third, and/or fourth-year students; second stage: random selection of class participants from each school). The survey consisted of 12 modules with a total of 71 questions on preventive factors and behaviors, including risk behaviors linked to the health of second, third, and fourth-year students. A total of 2882 students at 50 public education institutions participated in the study, which translates to the following response rates: school level, 100%; student level, 85%; total, 85%. Details on the design, data collection, study instrument, and other aspects of the survey can be found in the GSHS report[9].

The study variables were defined using the method described in McKinnon et al.[10]. The most relevant dependent variables were suicidal ideation (probed with the question: "During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?) and suicidal planning (probed with the question: "During the last 12 months, did you make a plan about how you would attempt suicide?) in the last 12 months. Independent variables were sex; age; support from parents in the last 30 days (“frequently/always,” “sometimes,” “never/rarely”); feeling of loneliness in last 12 months (“never,” “sometimes/rarely,” “frequently/always”); food insecurity in the last 30 days (“never,” “sometimes/rarely,” “frequently/always”); number of good friends (“three or more,” “one or two,” “none”); number of physical attacks in the last 12 months (“none,” “one,” “two or more”); number of days of bullying in the last 30 days (“none,” “one to two,” “three or more”); number of days of smoking in the last 30 days (“none,” “one to two,” “three or more”); and number of days that alcohol was consumed in the last 30 days (“none,” “one to five,” “six or more”).

Statistical analysis

The GSHS databases are available to the public and can be accessed through the WHO web portal11. The database for GSHS 2010 was processed and analyzed using statistical software Stata v14.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). In the first stage of the survey, the categorical variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages. In the second stage, bivariate and multivariate analyses were carried out for each independent variable to determine any associations with suicidal ideation and suicidal ideation plus suicidal planning, using generalized linear models with Poisson distribution and log link function, as well as weighting factors, to address the complex sample design. For the multivariate analysis, we included independent variables with a p-value < 0.2 in the bivariate analysis and reported prevalence ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). In all of the analyses, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics

This study did not require approval from an ethics committee as it is based on an analysis of secondary data freely accessible in the public domain without information that could identify the adolescents surveyed.

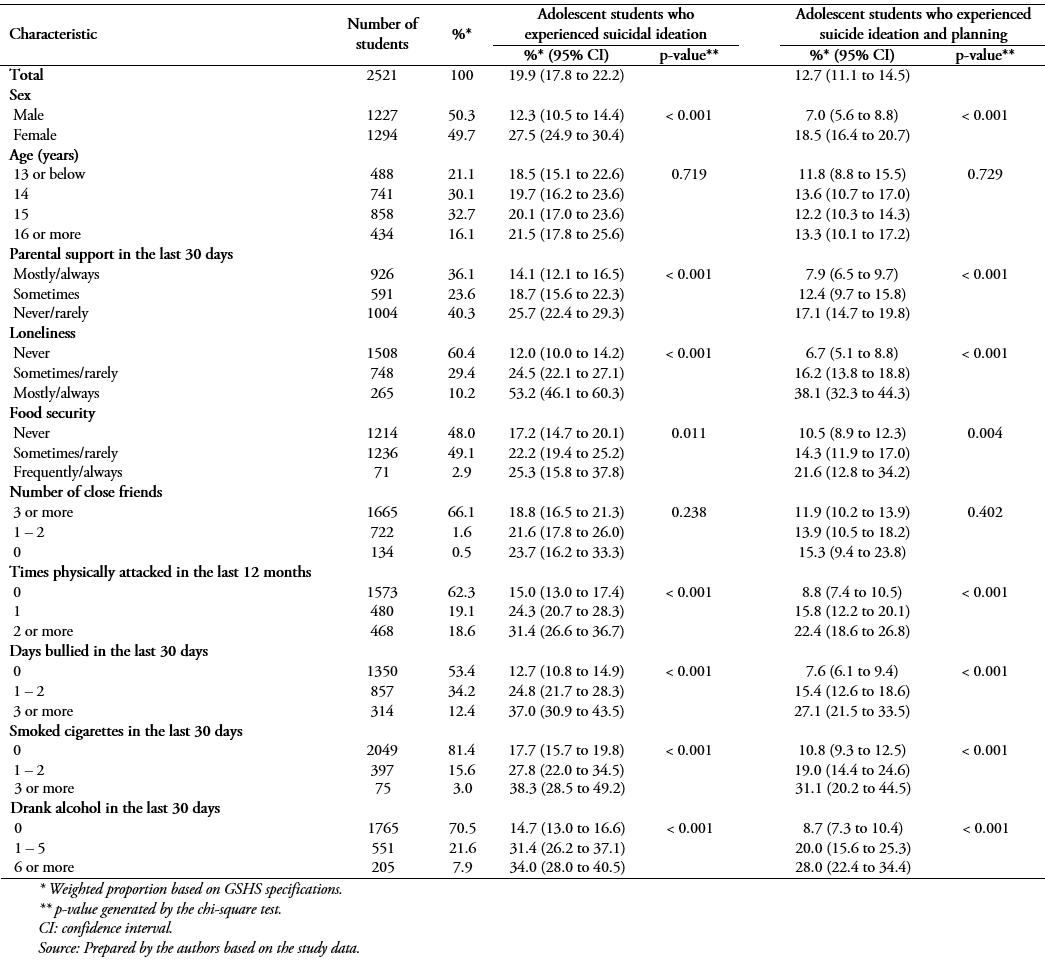

The GSHS 2010 obtained data for a total of 2521 schoolchildren, providing a complete data set for the study variables (suicidal behaviors and associated risk factors). The majority of the students surveyed were female, and the most common age was 15 years (32.7%).

Of the adolescents studied, 40.3% said they had not received parental support in the last 30 days; 39.6% said they had felt lonely in the last 12 months; 48% reported adequate food supply in last 30 days; 66.1% reporting having three or more good friends; 37.7% said they had experienced one or more physical attacks in the last 12 months; 46.6% reported being bullied at least once in the last 30 days. In response to the questions about behavior in the last 30 days, 18.6% said they had smoked, and 7.9% said they had consumed alcohol six or more times.

A total of 19.9% of the study sample (95% CI: 17.8 to 22.2) reported suicidal ideation in the last 12 months, and 12.7% (95% CI: 11.1 to 14.5) reported ideation plus suicidal planning. Females had a higher prevalence of ideation (27.5%, 95% CI: 24.9 to 30.4) and ideation plus suicidal planning (18.5%, 95% CI: 16.4 to 20.7) than males, who reported these behaviors 50% less frequently than females (Table 1). Adolescent students who said they had little or no support from their parents in the last 30 days had a higher prevalence of ideation (25.7%, 95% CI: 22.4 to 29.3) and ideation plus planning (17.1%, 95% CI: 14.7 to 19.8) than students who reported receiving parental support sometimes or frequently. Similarly, students who said they had frequent feelings of loneliness in the last 12 months had a higher prevalence of ideation (53.2%, 95% CI: 46.1 to 60.3) and ideation plus planning (38.1%, 95% CI: 32.3 to 44.3) than students who reported rarely or never feeling lonely. Adolescent students who reported frequent or prevalent food insecurity had a higher prevalence of ideation (25.3%, 95% CI: 15.8 to 37.8) and ideation plus planning (21.6%, 95% CI: 12.8 to 34.2) than those who did not report an inadequate food supply. Likewise, ideation and planning were more prevalent in students who had experienced two or more episodes of physical aggression in the last 12 months (31.4% and 22.4% respectively) and in those who had experienced more days of bullying in the last 30 days (37.0% and 27.1% respectively). A higher prevalence of ideation and ideation plus suicide planning was found in students who said they had smoked three or more days in the last 30 days (38.3% and 31.1% respectively) and in those who said they had consumed alcohol on six or more days in the same period (34.0% and 28.0% respectively).

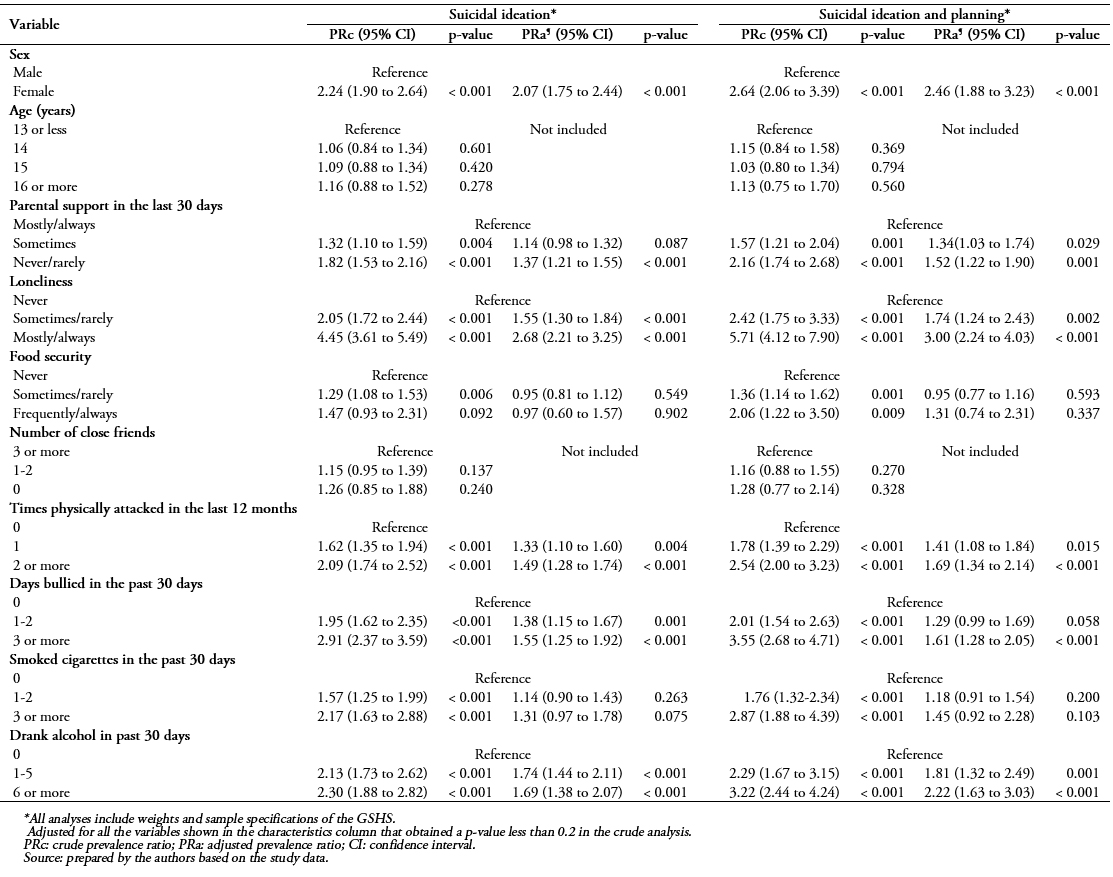

The bivariate model (Table 2) showed that the following variables were associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal ideation plus planning: sex, parental support in the last 30 days, feelings of loneliness in the last 12 months, food insecurity in the last 30 days, number of episodes of physical aggression in the last 12 months, number of days experiencing bullying in the last 30 days, number of days in which they smoked cigarettes in the last 30 days, and number of days in which they consumed alcohol in the last 30 days. In the adjusted model, it was found that being female (prevalence ratio [PR] = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.75 to 2.44); rarely or never having parental support (PR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.21 to 1.55); feeling lonely in the last 12 months (“sometimes/rarely”: PR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.30 to 1.84, “frequently/always”: PR = 2.68, 95% CI: 2.21 to 3.25); experiencing physical aggression in the last 12 months (“once” [PR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.10 to 1.60], “two or more times” [PR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.28 to 1.74]); experiencing bullying in the last 30 days ( “1-2 days” [PR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.15 to 1.67], “3 or more days” [PR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.25 to 1.92]); and consuming alcohol in the last 30 days (“one to five days” [PR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.44 to 2.11] or “six days or more” [PR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.38 to 2.07]) were associated with suicidal ideation.

The following variables were related to the presence of ideation plus suicidal planning: being female (PR = 2.46, 95% CI: 1.88 to 3.23); receiving some parental support in the last 30 days (PR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.03 to 1.74) or rarely or never receiving parental support (PR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.22 to 1.90); having felt loneliness in the last 12 months (“sometimes/rarely” [PR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.24 to 2.43], “frequently/always” [PR = 3.00, 95% CI: 2.24 to 4.03]); having experienced physical aggression in the last 12 months (“once” [PR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.84], “two or more times” [PR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.34 to 2.14]); having experienced bullying three or more days in the last 30 days (PR = 1.61, 95% CI: 1.28 to 2.05); and having drunk alcohol in the last 30 days (“one to five days” [PR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.32 to 2.49], “six days or more” [PR = 2.22, 95% CI: 1.63 to 3.03]).

This work sought to measure the prevalence of ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning and associated factors in Peruvian adolescent students using a national database. The study results showed that 2 out of 10 adolescent students presented suicidal ideation, and at least 1 in 10 presented ideation plus suicidal planning in the last 12 months. The prevalence of both factors was more than double for females versus males. In addition to sex, rarely or never having parental support in the previous 30 days, experiencing physical aggression or feeling lonely in the last 12 months, and experiencing bullying or drinking alcohol in the last 30 days were associated with presenting ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning.

The prevalence of suicidal ideation in adolescent students in Peru was close to the overall prevalence (16.9%) reported in the 59 low and middle-income countries (LMICs) where the GSHS 2010 (which includes data collected between 2003 and 2015) has been carried out[4]. Analysis of the GSHS in the 59 LMICs showed a global prevalence of suicide planning of 17.0%[4]. This last value indicates that the prevalence of suicidal planning in Peruvian adolescent students was lower than the mean reported in LMICs. The results on suicidal ideation and planning were similar to those reported by a pre-university studies center in the capital of Peru attended by students from different regions of the country[12] and by a study based on the GSHS conducted at two sites in the Peruvian capital[13]. Given that almost one-quarter of suicides in Peru occur in people 10 to 19 years old, suicidal behaviors seem to be prevalent in the Peruvian adolescent population.

The prevalence of ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning was higher in adolescent female students. This finding is consistent with the results of studies on the prevalence of ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning carried out by the GSHS and in cohort studies conducted in adolescents[4],[10]. A higher prevalence of suicidal behavior in adolescent females may be caused by a higher prevalence of conditions such as anxiety, depression, and psychosocial problems based on gender[14],[15],[16],[17],[18]. The female/male ratio for the presence of ideation or ideation plus suicidal planning in Peruvian adolescent students was higher than 2:1. The multi-country GSHS study of 59 LMICs, which included data up to 2015, reported differences by sex in the prevalence of ideation (18.5% in women and 15.1% in men), with female prevalence in the Americas almost double that for males (22.1% in women and 12.8% in men)—the most significant difference by sex[4]. Similarly, the prevalence of suicidal ideation in LMICs was higher in women (18.2% in women and 15.6% in men), and the most considerable difference by sex was in the Americas region (19.9% for women and 12.1% for men)[4]. Thus, the prevalence of ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning in Peruvian adolescent students in this study was in line with what has been reported elsewhere for the Americas region showing that female students had a higher prevalence of suicidal behaviors, such as ideation or planning, compared to their male counterparts.

Factors such as having experienced bullying and physical aggression were associated with a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and planning in adolescent students in Peru. Regarding bullying, it has been reported that in 2015, 75.3% of girls and boys 9 to 11 years old had been victims of violence by their peers in educational institutions at some point in their lives, with 51.5% of cases female and an increase in case frequency of 0.9 percentage points compared to 2013[19]. Furthermore, 75% of Peruvian students said they had been victims of verbal or physical aggression by their classmates[19]. Half of the students do not seek help, and those with physical limitations were more prone to experiencing physical attacks[19]. Harassment, bullying, and physical aggression have been associated with suicidal behavior in the literature[4],[10],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24]. Hence, social support strategies must include school-level programs that support students who suffer from these problems, and training for professional staff at educational centers to help detect them.

Adolescent students who reported not receiving any or receiving very little parental support had a higher prevalence of ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning compared to students without this characteristic, as did students who reported feeling lonely. Feeling lonely and not receiving parental support has been described as being associated with suicidal behavior[4],[10],[25]. Regarding social support, although having close friends has been reported in the literature as a social support factor that can help prevent suicide, this factor was not found to be associated with suicide ideation or planning in Peruvian schoolchildren[26],[27]. Another potential source of social support is school support, provided by the educational institutions themselves[26],[28]. This factor was not studied in the GSHS survey, so we could not study its relationship with suicidal ideation or planning in Peruvian adolescent students. Taking all of these results into account, it seems essential to emphasize parental support in strategies for prevention and control of suicide in adolescents.

Alcohol consumption is associated with suicidal behavior in Peruvian adolescent students. Although smoking, abuse of substances such as cannabis or other illicit drugs, and exposure to self-inflicted personal injuries have been widely reported as being associated with suicide[29],[30],[31],[32], smoking was not found to be associated with suicidal behavior in the population studied. Exposure to many of these factors by groups with other risky behaviors, such as adolescents who suffer from physical self-harm or behaviors that reflect poor social adaptation, induces an increased risk of suicide[33]. Therefore, it is important to detect people with suicidal ideation or planning in higher-risk groups and, in the Peruvian context, highlight the consumption of alcohol as a factor associated with suicidal behavior in adolescent students[32].

Deaths due to suicide can be prevented. Given that suicide is one of the main causes of mortality in adolescents, ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning are associated with suicide, and the prevalence of these suicidal behaviors is significant in the adolescent school population of Peru, interventions that seek to reduce suicide attempts should be able to identify adolescents who present suicidal behaviors. In line with the WHO proposal to reduce suicide mortality by 10% by 2020, in April 2019 the Government of Peru enacted the "Mental Health Law," which guarantees every citizen the right to enjoy the highest possible level of mental health, without any discrimination; the right to free and voluntary access to public and private mental health services; and the right to receive timely attention for any mental health problems they present[34]. Furthermore, the Peruvian Ministry of Health has included mental health as one of its national research priorities for 2019-2023 in order to promote the generation and transfer of scientific and technical knowledge[35].

The limitations of this study include its cross-sectional design, which precluded the identification of relationships between the socio-demographic factors studied and suicidal ideation or planning. The data source was another potential limitation; GSHS data is self-reported whereby recall bias and social desirability bias could be present. Likewise, GSHS in Peru does not collect information on suicide attempts, which would have been useful in determining the degree of association between suicide ideation and planning. It also does not collect data on adolescents who do not attend public school. Hence, the results are representative only of Peruvian adolescents attending public schools. Finally, the most recent GSHS data for Peru are from 2010, so risk factors associated with suicidal behaviors could have changed, and comparability of the results with more recent studies about suicide and suicidal behaviors in Peruvian adolescents is limited. Despite these limitations, the GSHS is a multi-country survey that has provided data on mental health since 2003 using a nationally representative sample of public school students, allowing for not only the study of suicide in various LMICs but also comparisons between countries. These data may be useful in understanding the state of suicidal behavior in the countries where the questionnaire was carried out, including Peru.

In conclusion, ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning is a problem in the Peruvian adolescent population, with females presenting the highest prevalence of suicidal behaviors. Strategies against suicide in the adolescent student population should take into account the identification of suicidal behaviors and contributing factors such as the lack of social support (parental), harassment (bullying and physical abuse), and alcohol consumption to prioritize interventions in groups with higher risk.

Authorship contributions

AHV: conceptualization, supervision, methodology, data preservation, and project management. GBQ: supervision and project management. GBQ, AHV, RVF, ETL, and DDS: writing, review, and editing.

Acknowledgments

To the Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática in Peru for making public the necessary databases for the conduct of this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding sources

This study was self-funded.

Data source

Microdatos INEI: http://iinei.inei.gob.pe/microdatos/

Table 1. Prevalence of suicidal behaviors in public school adolescent students in the last 12 months by selected socio-demographic factors. GSHS Peru, 2010.

Table 1. Prevalence of suicidal behaviors in public school adolescent students in the last 12 months by selected socio-demographic factors. GSHS Peru, 2010.

Table 2. Factors associated with suicidal behavior in public school adolescent students in the last 12 months. GSHS Peru (2010).

Table 2. Factors associated with suicidal behavior in public school adolescent students in the last 12 months. GSHS Peru (2010).

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Introduction

Adolescence is one of the stages in life most affected by suicide. In Peru, 22% of suicides occur in people 10 to 19 years old. However, mental health overall and factors associated with suicidal behaviors have not been well studied.

Objective

To determine the prevalence of suicidal behaviors (ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning) and associated factors in Peruvian adolescent students.

Methods

A cross-sectional study analyzing data from the Global School-based Student Health Survey for Peru in 2010 was conducted to measure the prevalence of suicidal behaviors (ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning) and associated factors in Peruvian adolescent students.

Results

Of the 2521 students evaluated, 19.9% (95% CI: 17.8 to 22.2) presented suicidal ideation and 12.7% (95% CI: 11.1 to 14.5) presented suicidal planning in the last 12 months. Females had a higher prevalence of both ideation (27.5%, 95% CI: 24.9 to 30.4) and ideation plus suicidal planning (18.5%, 95% CI: 16.4 to 20.7). Multivariate analysis found that being female, having little parental support, having felt loneliness, having suffered from physical aggression, having been bullied, and alcohol consumption, were associated with ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning in adolescent students.

Conclusion

Ideation and ideation plus suicidal planning is a problem in the Peruvian adolescent population and is associated with several factors. Strategies are needed to identify and register suicide in adolescents in Peru and to develop prevention programs.

Autores:

Akram Hernández-Vásquez[1], Rodrigo Vargas-Fernández[2], Deysi Díaz-Seijas[3,4], Elena Tapia-López[5], Guido Bendezu-Quispe[6]

Autores:

Akram Hernández-Vásquez[1], Rodrigo Vargas-Fernández[2], Deysi Díaz-Seijas[3,4], Elena Tapia-López[5], Guido Bendezu-Quispe[6]

Citación: Hernández-Vásquez A, Vargas-Fernández R, Díaz-Seijas D, Tapia-López E, Bendezu-Quispe G. Prevalence of suicidal behaviors and associated factors among Peruvian adolescent students: an analysis of a 2010 survey. Medwave 2019;19(11):e7753 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2019.11.7753

Fecha de envío: 5/9/2019

Fecha de aceptación: 20/11/2019

Fecha de publicación: 26/12/2019

Origen: No solicitado

Tipo de revisión: Revisado por cuatro pares revisores externos a doble ciego

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Viner RM, Haller DM, Bose K, et al. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2009 Sep 12;374(9693):881-92. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Viner RM, Haller DM, Bose K, et al. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2009 Sep 12;374(9693):881-92. | CrossRef | PubMed | Uddin R, Burton NW, Maple M, Khan SR, Khan A. Suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts among adolescents in 59 low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019 Apr;3(4):223-233. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Uddin R, Burton NW, Maple M, Khan SR, Khan A. Suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts among adolescents in 59 low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019 Apr;3(4):223-233. | CrossRef | PubMed | Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, et al. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2016 Jan;46(2):225-36. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, et al. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2016 Jan;46(2):225-36. | CrossRef | PubMed | Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. | CrossRef | PubMed | Instituto Nacional de Salud Mental Honorio Delgado – Hideyo Noguchi. 64 casos de intentos de suicidio entre escolares. Lima 2018. [on line] | Link |

Instituto Nacional de Salud Mental Honorio Delgado – Hideyo Noguchi. 64 casos de intentos de suicidio entre escolares. Lima 2018. [on line] | Link | Hernández-Vásquez A, Azañedo D, Rubilar-González J, Huarez B, Grendas L. [Evolution and regional differences in mortality due to suicide in Peru, 2004-2013]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2016 Oct-Dec;33(4):751-757. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hernández-Vásquez A, Azañedo D, Rubilar-González J, Huarez B, Grendas L. [Evolution and regional differences in mortality due to suicide in Peru, 2004-2013]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2016 Oct-Dec;33(4):751-757. | CrossRef | PubMed | Ministerio de Salud. Encuesta Global de Salud Escolar. Resultados – Perú 2010. 2010. [on line]. | Link |

Ministerio de Salud. Encuesta Global de Salud Escolar. Resultados – Perú 2010. 2010. [on line]. | Link | McKinnon B, Gariépy G, Sentenac M, Elgar FJ. Adolescent suicidal behaviours in 32 low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 May 1;94(5):340-350F. | CrossRef | PubMed |

McKinnon B, Gariépy G, Sentenac M, Elgar FJ. Adolescent suicidal behaviours in 32 low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 May 1;94(5):340-350F. | CrossRef | PubMed | World Health Organization. Global school-based student health survey (GSHS) 2019. [on line] | Link |

World Health Organization. Global school-based student health survey (GSHS) 2019. [on line] | Link | Muñoz J, Pinto V, Callata H, Napa N, Perales A. Ideación suicida y cohesión familiar en estudiantes preuniversitarios entre 15 y 24 años, Lima 2005. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2006;23(4):239-46. | Link |

Muñoz J, Pinto V, Callata H, Napa N, Perales A. Ideación suicida y cohesión familiar en estudiantes preuniversitarios entre 15 y 24 años, Lima 2005. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2006;23(4):239-46. | Link | Sharma B, Nam EW, Kim HY, Kim JK. Factors Associated with Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt among School-Going Urban Adolescents in Peru. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015 Nov 20;12(11):14842-56. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sharma B, Nam EW, Kim HY, Kim JK. Factors Associated with Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt among School-Going Urban Adolescents in Peru. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015 Nov 20;12(11):14842-56. | CrossRef | PubMed | Breslau J, Gilman SE, Stein BD, Ruder T, Gmelin T, Miller E. Sex differences in recent first-onset depression in an epidemiological sample of adolescents. Transl Psychiatry. 2017 May 30;7(5):e1139. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Breslau J, Gilman SE, Stein BD, Ruder T, Gmelin T, Miller E. Sex differences in recent first-onset depression in an epidemiological sample of adolescents. Transl Psychiatry. 2017 May 30;7(5):e1139. | CrossRef | PubMed | Brezo J, Paris J, Turecki G. Personality traits as correlates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006 Mar;113(3):180-206. | PubMed |

Brezo J, Paris J, Turecki G. Personality traits as correlates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006 Mar;113(3):180-206. | PubMed | Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017 Aug;143(8):783-822. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017 Aug;143(8):783-822. | CrossRef | PubMed | Mallon S, Galway K, Hughes L, Rondón-Sulbarán J, Leavey G. An exploration of integrated data on the social dynamics of suicide among women. Sociol Health Illn. 2016 May;38(4):662-75. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Mallon S, Galway K, Hughes L, Rondón-Sulbarán J, Leavey G. An exploration of integrated data on the social dynamics of suicide among women. Sociol Health Illn. 2016 May;38(4):662-75. | CrossRef | PubMed | Vijayakumar L. Suicide in women. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015 Jul;57(Suppl 2):S233-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Vijayakumar L. Suicide in women. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015 Jul;57(Suppl 2):S233-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Instituto Nacional Estadística Informática. Encuesta Nacional sobre Relaciones Sociales ENARES 2013 y 2015 (Principales Resultados) 2016 [on line]. | Link |

Instituto Nacional Estadística Informática. Encuesta Nacional sobre Relaciones Sociales ENARES 2013 y 2015 (Principales Resultados) 2016 [on line]. | Link | Sigurdson JF, Undheim AM, Wallander JL, Lydersen S, Sund AM. The Longitudinal Association of Being Bullied and Gender with Suicide Ideations, Self-Harm, and Suicide Attempts from Adolescence to Young Adulthood: A Cohort Study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018 Apr;48(2):169-182. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sigurdson JF, Undheim AM, Wallander JL, Lydersen S, Sund AM. The Longitudinal Association of Being Bullied and Gender with Suicide Ideations, Self-Harm, and Suicide Attempts from Adolescence to Young Adulthood: A Cohort Study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018 Apr;48(2):169-182. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bauman S, Toomey RB, Walker JL. Associations among bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide in high school students. J Adolesc. 2013 Apr;36(2):341-50. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bauman S, Toomey RB, Walker JL. Associations among bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide in high school students. J Adolesc. 2013 Apr;36(2):341-50. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kim YS, Koh YJ, Leventhal B. School bullying and suicidal risk in Korean middle school students. Pediatrics. 2005 Feb;115(2):357-63. | PubMed |

Kim YS, Koh YJ, Leventhal B. School bullying and suicidal risk in Korean middle school students. Pediatrics. 2005 Feb;115(2):357-63. | PubMed | Pranjić N, Bajraktarević A. Depression and suicide ideation among secondary school adolescents involved in school bullying. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2010;11(4):349-62. | CrossRef |

Pranjić N, Bajraktarević A. Depression and suicide ideation among secondary school adolescents involved in school bullying. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2010;11(4):349-62. | CrossRef | Geoffroy MC, Boivin M, Arseneault L, Turecki G, Vitaro F, Brendgen M, et al. Associations Between Peer Victimization and Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt During Adolescence: Results From a Prospective Population-Based Birth Cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Feb;55(2):99-105. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Geoffroy MC, Boivin M, Arseneault L, Turecki G, Vitaro F, Brendgen M, et al. Associations Between Peer Victimization and Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt During Adolescence: Results From a Prospective Population-Based Birth Cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Feb;55(2):99-105. | CrossRef | PubMed | Sharma B, Lee TH, Nam EW. Loneliness, Insomnia and Suicidal Behavior among School-Going Adolescents in Western Pacific Island Countries: Role of Violence and Injury. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Jul 15;14(7). pii: E791. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sharma B, Lee TH, Nam EW. Loneliness, Insomnia and Suicidal Behavior among School-Going Adolescents in Western Pacific Island Countries: Role of Violence and Injury. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Jul 15;14(7). pii: E791. | CrossRef | PubMed | Miller AB, Esposito-Smythers C, Leichtweis RN. Role of social support in adolescent suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. J Adolesc Health. 2015 Mar;56(3):286-92. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Miller AB, Esposito-Smythers C, Leichtweis RN. Role of social support in adolescent suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. J Adolesc Health. 2015 Mar;56(3):286-92. | CrossRef | PubMed | Chang EC, Chang OD, Martos T, Sallay V, Lee J, Stam KR, et al. Family support as a moderator of the relationship between loneliness and suicide risk in college students: having a supportive family matters!. The Family Journal. 2017;25(3):257-63. | CrossRef |

Chang EC, Chang OD, Martos T, Sallay V, Lee J, Stam KR, et al. Family support as a moderator of the relationship between loneliness and suicide risk in college students: having a supportive family matters!. The Family Journal. 2017;25(3):257-63. | CrossRef | Robinson J, Cox G, Malone A, Williamson M, Baldwin G, Fletcher K, et al. A systematic review of school-based interventions aimed at preventing, treating, and responding to suicide- related behavior in young people. Crisis. 2013;34(3):164-82. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Robinson J, Cox G, Malone A, Williamson M, Baldwin G, Fletcher K, et al. A systematic review of school-based interventions aimed at preventing, treating, and responding to suicide- related behavior in young people. Crisis. 2013;34(3):164-82. | CrossRef | PubMed | Schilling EA, Aseltine RH Jr, Glanovsky JL, James A, Jacobs D. Adolescent alcohol use, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. J Adolesc Health. 2009 Apr;44(4):335-41. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Schilling EA, Aseltine RH Jr, Glanovsky JL, James A, Jacobs D. Adolescent alcohol use, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. J Adolesc Health. 2009 Apr;44(4):335-41. | CrossRef | PubMed | Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Sullivent EE 3rd. Age of alcohol use initiation, suicidal behavior, and peer and dating violence victimization and perpetration among high-risk, seventh-grade adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008 Feb;121(2):297-305. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Sullivent EE 3rd. Age of alcohol use initiation, suicidal behavior, and peer and dating violence victimization and perpetration among high-risk, seventh-grade adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008 Feb;121(2):297-305. | CrossRef | PubMed | Sher L, Zalsman G. Alcohol and adolescent suicide. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2005 Jul-Sep;17(3):197-203. | PubMed |

Sher L, Zalsman G. Alcohol and adolescent suicide. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2005 Jul-Sep;17(3):197-203. | PubMed | Mars B, Heron J, Klonsky ED, Moran P, O'Connor RC, Tilling K, et al. Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non-suicidal self-harm: a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Apr;6(4):327-337. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Mars B, Heron J, Klonsky ED, Moran P, O'Connor RC, Tilling K, et al. Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non-suicidal self-harm: a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Apr;6(4):327-337. | CrossRef | PubMed | Thullen MJ, Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ. Suicide Ideation and Attempts Among Adolescents Engaged in Risk Behaviors: A Latent Class Analysis. J Res Adolesc. 2016 Sep;26(3):587-594. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Thullen MJ, Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ. Suicide Ideation and Attempts Among Adolescents Engaged in Risk Behaviors: A Latent Class Analysis. J Res Adolesc. 2016 Sep;26(3):587-594. | CrossRef | PubMed | Republica del Perú, Presidente de la República, Congreso de la República. LEY Nº 30947. Ley de Salud Mental 2019. [on line]. | Link |

Republica del Perú, Presidente de la República, Congreso de la República. LEY Nº 30947. Ley de Salud Mental 2019. [on line]. | Link | Republica del Perú, Ministerio de Salud. Resolución Ministerial Nº 658-2019/MINSA: Prioridades nacionales de investigación en salud en Perú 2019 – 2023. MINSA; 2019. [on line]. | Link |

Republica del Perú, Ministerio de Salud. Resolución Ministerial Nº 658-2019/MINSA: Prioridades nacionales de investigación en salud en Perú 2019 – 2023. MINSA; 2019. [on line]. | Link |