Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Case-control study design has come as a significant contribution to scientific research, insofar as it has been the expression of the strengths and weaknesses present in observational epidemiology [1]. This type of study has been used for exploring a wide array of associations. An example of this was the first research devoted to the understanding of acquired immune deficiency syndrome [2]. The first research on this topic made it possible to detect a series of factors which were linked to disease transmission, such as: promiscuity, intravenous drug use, and transfusions, among others. This identification process in turn allowed for implementing various security measures, reducing the transmission speed of the virus, even before the virus itself had been identified [1],[2].

In this article, a brief description of the characteristics of case-control studies will be given, along with their strengths and main weaknesses, with a view to providing clinical professionals with the right way to interpret their findings.

Case-control design is a longitudinal, analytic, and observational type of study, wherein a search for history of exposure to a given factor is conducted based on the presence or absence of an event [1],[3],[4].

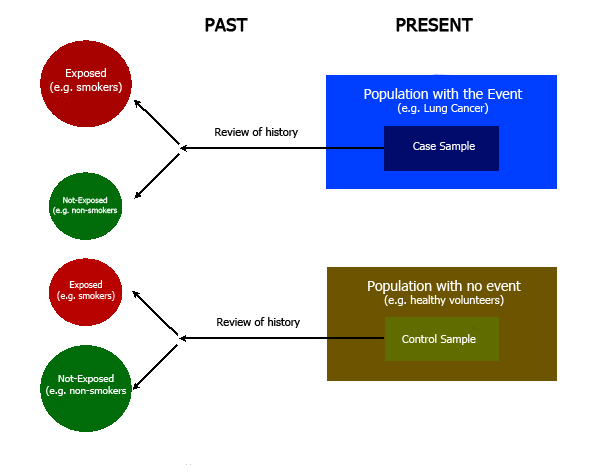

For example, in order to study the link between smoking and lung cancer, we can take a group of people who suffer from lung cancer (case group) along with a group of people who do not have lung cancer (control group). Then, we can look for smoking habits among the study participants. In this example, the latter is the exposure factor which will be assessed. Given that the event has already occurred, this means that we are dealing with an inherently retrospective study [1],[3],[4]. (Figure 1); the frequency of exposure within the control group can then be compared to that of the control group, thereby making it possible to calculate an association measurement [4],[5],[6].

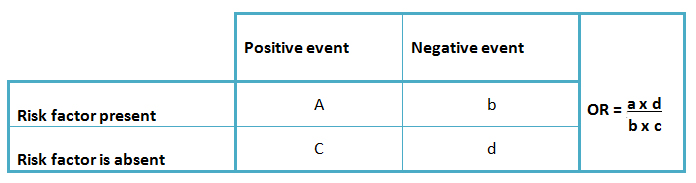

Due to the characteristics of this design, it is not possible to estimate incidence rates, relative risks, or attributable risks. Thus, for these studies the odds ratio is used as a statistic estimator (3), associated with its corresponding confidence intervals. This provides a quantification of the link between the exposed and the non-exposed group. However, due to their estimation characteristics, they are not expressed as risks or probabilities [1],[2],[5]. (Table 1).

Table I. Odds ratio calculation

The final key point in this type of design is that the control group must be representative of the at-risk population with the potential to become a case [7]. Ideally, the participants should be randomly selected [5],[7].

Regarding the amount of controls that should be taken into account for every case, clinical professionals intuitively expect similar groups [8]. Nevertheless, sometimes the number of cases is small and cannot be increased. In this situation, an equally small number of controls would we weak in its ability to establish links [8],[9]. Thus, by increasing the number taking part in the control group to a roughly 4:1 ratio, the strength of the study will improve [9].

Compared to other types of studies, the case-control variety can provide significant results in a relatively short period of time, and requiring little resources [1],[10]. However this type of study tends to be more susceptible to design and analytical bias [1],[7],[10].

Case-control studies are useful when the incidence rate of an event is low, given that a cohort would have to provide follow-up on many people in order to identify one with the expected result [1],[3]. This design is also efficient in long latency disease research, in which case a cohort study would take many years of follow-up before any results come to light [1],[3],[10].

However, there are many methodological aspects affecting the validity of the results in case-control studies. It is of the utmost importance that a proper control group be selected [10]. In order to illustrate this concept, let us suppose that a certain study aims to assess whether non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prevent colorectal cancer [1]. If the control group was to be comprised of patients who are being hospitalized for digestive tract bleeding secondary to peptic ulcer disease, it would be unlikely that the latter used this type of drug. This would induce that notion that exposure (aspirin use) is more frequent among patients with colorectal cancer vis-à-vis the control group, solely based on the characteristics of the latter. This could lead to a greater disparity in terms of event occurrence. On the other hand, if patients with rheumatoid arthritis were used as the control group, among whom the use of this type of medication is more frequent, non-steroidal anti—inflammatory drugs could turn up as a protecting factor with regard to the occurrence of the event. The use of 95% confidence intervals could also offer an estimator for the precision of the finding, as well as determine the existence of statistical significance [11].

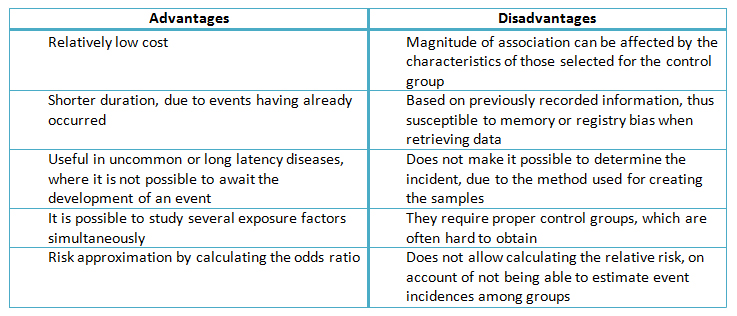

Another difficulty that arises with these designs is the retrospective nature of the exposure estimation, which is susceptible to the quality of the clinical records and memory problems [7]. Consequently, researchers who conduct case-control studies need to be aware of the possibility of an information bias, which is why it needs to be accounted for in the design, along with a description of the methods used to avoid it. An example of this practice would be to include photographs, journals and calendars, all of which can aid the participants in recalling the instances of exposure [7]. These and other characteristics are summarized in Table II.

Table II. Summary of advantages and disadvantages in case-control studies

Another important aspect are the confusion factors. This type of bias can be managed in the design through matching. This procedure makes it possible to take control over the associated variables. Nevertheless, it is generally preferred to manage it in the analysis phase through techniques such as logistic regression or stratified analysis [12].

Case-control studies that are well designed and carefully performed can provide useful and reliable results. However, a lot of attention must be devoted to selecting the control groups, as well as to measuring data on exposure in order to avoid potential biases that can diminish the strength of the study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Figure 1. Case-control design

Figure 1. Case-control design

Table I. Odds ratio calculation

Table I. Odds ratio calculation

Table II. Summary of advantages and disadvantages in case-control studies

Table II. Summary of advantages and disadvantages in case-control studies

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Autores:

Cristian Papuzinski Aguayo[1], Felipe Martínez Lomakin[2,3]

Autores:

Cristian Papuzinski Aguayo[1], Felipe Martínez Lomakin[2,3]

Citación: Papuzinski C, Martínez F. Case-control studies - the retrospective perspective. Medwave 2014;14(2):e5925 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2014.02.5925

Fecha de envío: 28/2/2014

Fecha de aceptación: 23/3/2014

Fecha de publicación: 27/3/2014

Origen: solicitado

Tipo de revisión: con revisión por cuatro pares revisores externos, a doble ciego

Citaciones asociadas

1. Editores. Masthead Mar;14(2). Medwave 2014;14(2):5932 | Link |

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Nombre/name: Soledad Briceño

Fecha/date: 2014-04-03 13:47:16

Comentario/comment:

Muy bien enfocado y presentado

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Case-control studies: research in reverse. Lancet. 2002 Feb 2;359(9304):431-4. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Case-control studies: research in reverse. Lancet. 2002 Feb 2;359(9304):431-4. | CrossRef | PubMed | Moss AR, Osmond D, Bacchetti P, Chermann JC, Barre-Sinoussi F, Carlson J. Risk factors for AIDS and HIV seropositivity in homosexual men. Am J Epidemiol. 1987 Jun;125(6):1035-47. | PubMed |

Moss AR, Osmond D, Bacchetti P, Chermann JC, Barre-Sinoussi F, Carlson J. Risk factors for AIDS and HIV seropositivity in homosexual men. Am J Epidemiol. 1987 Jun;125(6):1035-47. | PubMed | Grimes DA, Schulz KF. An overview of clinical research: the lay of the land. Lancet. 2002 Jan 5;359(9300):57-61. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Grimes DA, Schulz KF. An overview of clinical research: the lay of the land. Lancet. 2002 Jan 5;359(9300):57-61. | CrossRef | PubMed | Aschengrau A, Seage G. Essential of epidemiology in public health, 2nd. Ed. Mississauga, Canáda: Jones and Barlett Publishers, 2007.

Aschengrau A, Seage G. Essential of epidemiology in public health, 2nd. Ed. Mississauga, Canáda: Jones and Barlett Publishers, 2007.  Kelsey JL, Whittemore AS, Evans AS, Thompson WD. Methods in observational epidemiology. New York, United States: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Kelsey JL, Whittemore AS, Evans AS, Thompson WD. Methods in observational epidemiology. New York, United States: Oxford University Press, 1996.  Schlesselman J. Case-control studies: design, conduct, analysis. New York, United States: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Schlesselman J. Case-control studies: design, conduct, analysis. New York, United States: Oxford University Press, 1982.  Rothman KJ. Modern epidemiology. Boston, United States: Little, Brown and Company, 1986.

Rothman KJ. Modern epidemiology. Boston, United States: Little, Brown and Company, 1986.  Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Unequal group sizes in randomised trials: guarding against guessing. Lancet. 2002 Mar 16;359(9310):966-70. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Unequal group sizes in randomised trials: guarding against guessing. Lancet. 2002 Mar 16;359(9310):966-70. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wiebe DJ. Firearms in US homes as a risk factor for unintentional gunshot fatality. Accid Anal Prev. 2003 Sep;35(5):711-6. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wiebe DJ. Firearms in US homes as a risk factor for unintentional gunshot fatality. Accid Anal Prev. 2003 Sep;35(5):711-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Compared to what? Finding controls for case-control studies. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Compared to what? Finding controls for case-control studies. | CrossRef | PubMed | Madrid E, Martínez F. Statistics for the faint of heart – how to interpret confidence intervals and p values. Medwave 2014;14(1):5892. | CrossRef |

Madrid E, Martínez F. Statistics for the faint of heart – how to interpret confidence intervals and p values. Medwave 2014;14(1):5892. | CrossRef | Katz MH. Multivariable analysis: a practical guide for clinicians and public health researchers. Third edition. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Katz MH. Multivariable analysis: a practical guide for clinicians and public health researchers. Third edition. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2011.  Estadística para aterrorizados: interpretando intervalos de confianza y valores p

Estadística para aterrorizados: interpretando intervalos de confianza y valores p