Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Palabras clave: suicide, risk assessment, suicide attempted, psychiatric status rating scales

According to the World Health Organization, suicide has become a public health problem of global dimensions. Forty-five percent of suicide fatalities had consulted with a primary care doctor in the month preceding the event, but no suicide risk assessment had been conducted. Although suicide is an avoidable event, there is no standardized scale for assessment of suicide risk in the primary health care setting, where mental health care competencies vary and decisions are often guided by clinical judgment. A search and review of the best available evidence was carried out to identify scales for assessment of suicide risk for the nonspecialist doctor (i.e., ideally, brief, predictive, and validated). We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane, Epistemonikos, and Scholar Google. We also contacted national and international experts on the subject. We retrieved 3 092 documents, of which 2 097 were screened by abstract, resulting in 70 eligible articles. After screening by full text, 20 articles were selected from which four scales were ultimately extracted and analyzed. Our review concludes that there are no suicide risk assessment scales accurate and predictive enough to justify interventions based on their results. Positive predictive values range from 1 to 19%. Of the patients classified as "high risk," only 5% will die by suicide. Half of the patients who commit suicide come from "low-risk" groups. We also discuss 1) the importance of evaluating a patient with suicidal behavior according to socio-demographic variables, history of mental health problems, and stratification within a scale, and 2) possible initial actions in the challenging context of primary care.

|

Key ideas

|

Suicide is a complex problem caused by multiple factors. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), each year 800 000–1 000 000 people worldwide commit suicide, making it one of the five leading causes of death[1]. In Chile, there has been a progressive increase in general mortality rates due to suicide, which rose from 9.6 in the year 2000 to 11.8 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2011[2].

According to research, almost half of those who die from suicide consulted with a primary care physician in the month preceding the event, but medical records for these cases do not show an evaluation of suicide risk[3]. The “gold standard” for this type of evaluation is an interview by a psychiatrist[4], which is rarely available at the primary care level. Moreover, there is no standardized assessment for suicide risk applicable in the primary care setting (i.e., predictive and brief), where interventions are based on clinical judgment and expert recommendations[5].

To address the gaps described above, we conducted a search for systematic and nonsystematic reviews and primary research to identify standardized scales for evaluating suicide risk in adults in the primary care setting. We also evaluate the need to stratify patients according to suicide risk.

We carried out a bibliographic search in PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and Epistemonikos databases, using the keywords suicide, attempted suicide, risk assessment, psychiatric status rating scales, suicide risk scales, and suicide risk assessment to identify the available material, and selecting the research that met the search criteria (search strategy available in Supplementary Material). The inclusion criteria were: systematic or nonsystematic review, or primary research, that examined the validity and predictive capacity of scales for assessing suicide risk in adults in outpatient settings. The exclusion criteria were: research focused on populations with specific mental health diagnoses (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia); scales used to determine drug efficacy; scales used to evaluate specific populations (e.g., older adults, military, prisoners, pregnant women); scales designed for hospital use only, including emergency services; scales that evaluated suicide risk to predict readmission; letter-type reviews; opinions; clinical case studies; anecdotal material; and studies published more than 20 years ago (i.e., before 1999). International guidelines on suicide[6],[7],[8] the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5[9], and Chilean guidelines from the Ministry of Health were also consulted[10].

We also consulted with experts. In the international realm, we contacted members of The Columbia Lighthouse Project, creators of the Columbia scale (C-SSRS), who provided information regarding the use of this scale as a method of assessing suicide risk in the Latin American population. At the national level, we spoke with nurse Irma Rojas Moreno, author of the "National Program for Suicide Prevention of Suicide: Guidelines for its Implementation"[10], and with child and youth psychiatrist Dr. Vania Martínez N., an academic at the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the University of Chile’s School of Medicine.

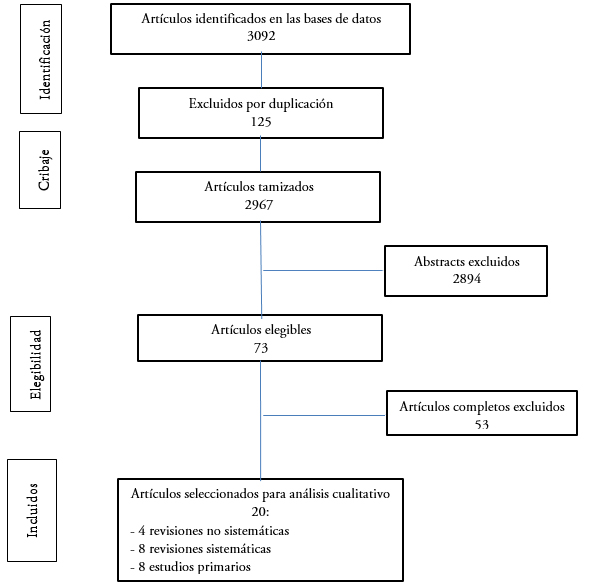

We identified 3092 articles and screened 2971. Screening by title and abstract eliminated 2894 articles, resulting in 73 eligible articles for full-text review. Of these, we eliminated 53 more based on the exclusion criteria (including “evaluated different outcomes”) (see Supplementary Material for a list of excluded studies and explanation of the exclusions). A total of 20 articles—four non-systematic reviews[5],[11],[12],[13] (Table 1); eight systematic reviews[14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21] (Table 2); and eight primary studies[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29] (Figure 1 flowchart)—were selected for our comparative and summary analysis

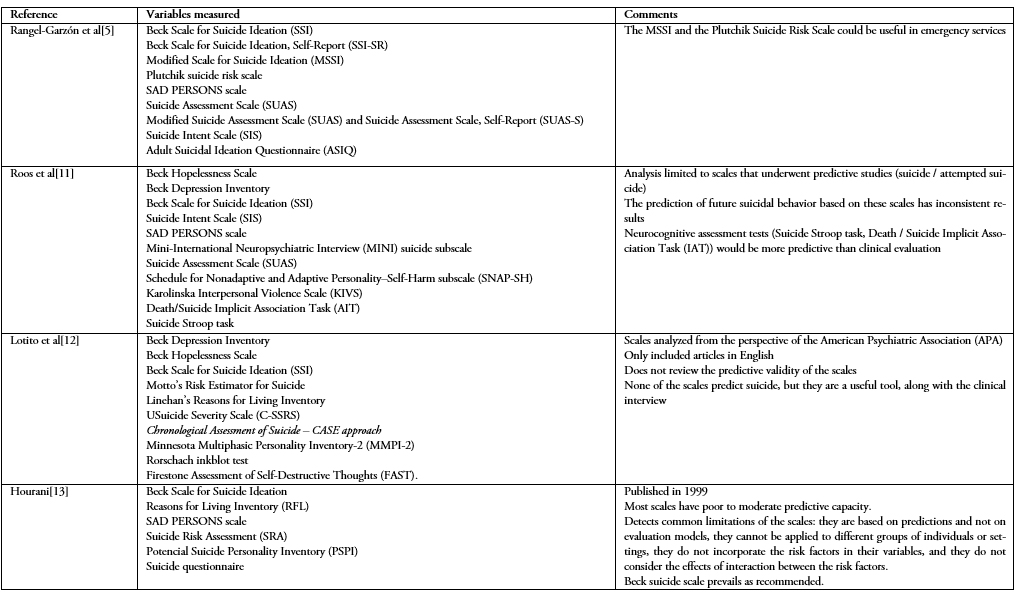

Table 1. Summary of results reported by the non-systematic reviews.

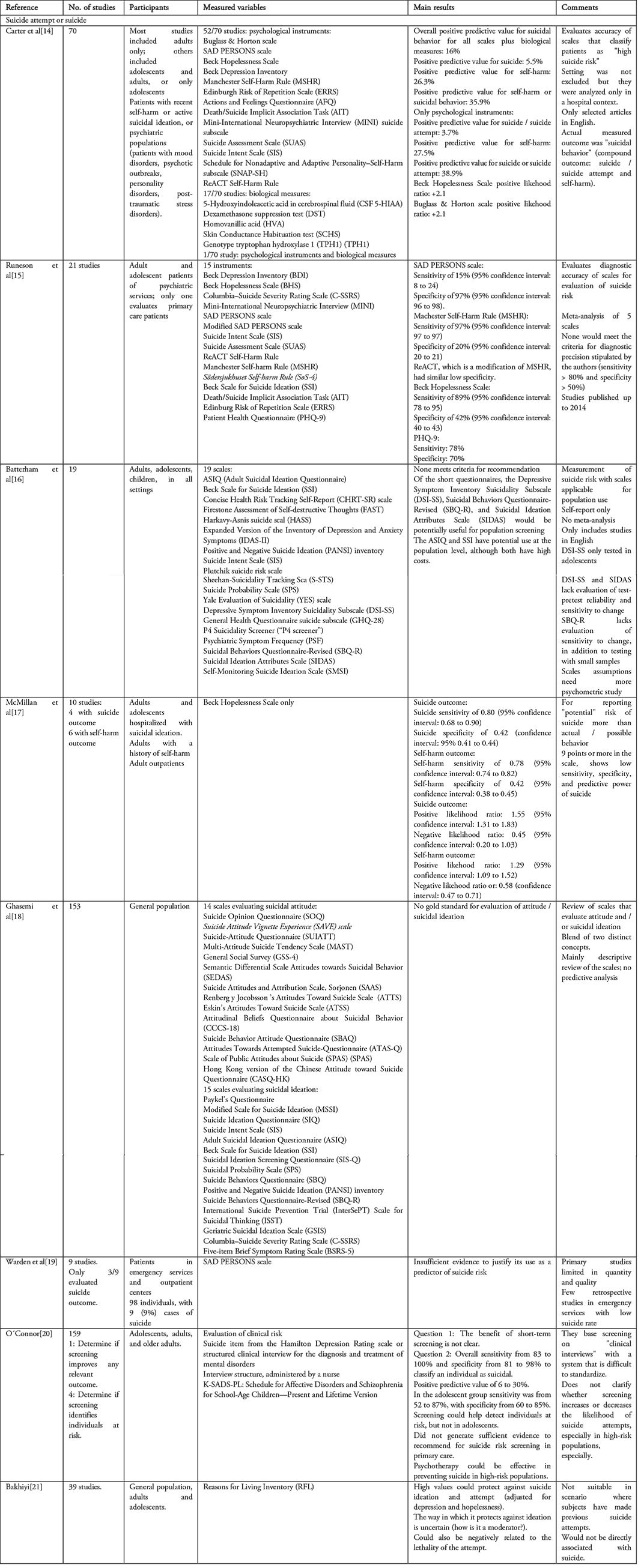

Table 2. Summary of results reported by the systematic reviews.

Figure 1. Flowchart of article selection process.

Scales for assessing suicide risk

The Suicide Assessment Scale (SUAS) includes 20 items scored from 0 to 4, has an estimated application time of 20 to 30 minutes, and (like the modified, interview version of the SUAS, and the self-report version, SUAS-S) must be administered by trained health personnel[5]. The scale measures 20 areas: sadness / despondency, hostility, energy, hypersensitivity, emotional loss/withdrawal, initiative, loss of perceived control, tension, anxiety, somatic concern, impulsiveness, loss of self-esteem, hopelessness, inability to feel (depersonalization), poor tolerance of frustration, suicidal thoughts, suicide intention, desire to die, lack of reasons to live, suicidal actions. In his study Niméus provides a cutoff of 39 as a predictor of suicide, with a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 86.3%, and positive predictive value of 19.4%[26].

The SUAS has the following disadvantages: it must be administered by personnel trained in mental health, it has low sensitivity and low positive predictive value, and it has only been tested in subjects who have previously attempted suicide. One review describes it as a scale that assesses changes in patients who are suicidal and those who have attempted suicide[13].

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a self-report scale that includes 21 items assessing depression severity. Each item is scored from 0 to 3, for a total possible score of 0 to 63, with defined cutoffs for different levels of severity (0 to 9, “symptoms”; 10 to 16, “mild depression”; 17 to 29, “moderate depression”; and 30 to 63, “severe depression”). Studies show the scale has 63 to 77% sensitivity and 64 to 80% specificity, for hospital and outpatient settings respectively, and takes approximately 20 minutes to administer[11],[12],[14],[22]. A 20-year prospective study evaluates the predictive capacity of the scale’s suicide item ("I have no thoughts of suicide” / “sometimes I think of committing suicide, but I would not commit suicide” / “suicide” / “I would commit suicide if I had the chance”) with regard to suicide deaths and suicide attempts and shows that a score of 1 for suicide and 2 for attempted suicide would be predictive within one year of follow-up. The authors emphasize that these values should serve as indicators for more in-depth evaluation, but do not rule out the same course of action for a score of 0, especially if a patient has previously attempted suicide. Despite the results of the prospective study, use of this scale’s suicide item for suicide risk screening has been strongly criticized because stratification is based on self-report for a single scale item[29].

Another self-report scale is the Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (ASIQ), in which 25 items scored at 0 to 7 measure cognitions underpinning suicide ideation and frequency of suicide ideation in past month. This scale has generated results that are strongly associated with those from the Beck Hopelessness Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory, but it has only been used in young populations (people ≤ 24 years old) and has not been included in any predictive studies. This scale has shown potential for use in population studies[5],[16],[18].

The Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) includes 15 items designed to measure the subject’s actual expectation of dying from a suicide attempt. The first eight questions are objective, gathering data about any recent suicide attempt, and the remaining seven questions are subjective. This scale is criticized for the incongruity of these two sets of items, as patients tend to overstate their answers to the subjective questions in seeking social gain or justification for their actions. This scale is not suitable in scenarios where few subjects have previously attempted suicide and/or most suicides occur in the first attempt[5],[11],[28].

The five-item Brief Symptom Rating Scale (BSRS-5) is a short screening test for psychiatric morbidity in diverse contexts and is mainly administered in Asia (to hospitalized patients and community subjects). It includes five questions scored on a Likert scale (0 to 4) that measure anxiety, depression, hostility, interpersonal hypersensitivity, and insomnia. Its broader, revised version, the BSRS-5R, has an additional, sixth question (“Do you have any suicide ideation?”) for evaluating suicidal ideation[28]. In a cross-sectional study the BSRS-5R showed sensitivity of 89%, specificity of 85%, a negative predictive value of 99%, and a positive predictive value of 11%, with an optimal cutoff point of tres for detecting suicide ideation in community subjects[28]. The revised scale had good internal consistency, showing that subjects with a high level of emotional stress have the highest positive response rate to the sixth question. The revised scale is brief and easy to apply but is not designed to predict suicide attempt; it is more suitable as an indicator for more indepth evaluation of suicidal tendancies, and for detecting severity of psychopathology, reaffirming the idea that people with suicidal ideation tend to have axis I and / or axis II diagnoses. It has not been tested in prospective cohort studies[28].

The Reasons for Living Inventory is a self-administered instrument that measures factors protective against suicide through 48 items rated on a Likert scale of 0 (“not important”) to 6 (“extremely important”). The six groups of variables measured are: survival and coping beliefs, moral objections to suicide, responsibility to the family, issues related to children, fear of suicide, and fear of social disapproval. It does not have a standardized cutoff point; the higher the score, the greater the reasons to live. A systematic review showed a consistent negative association between the score on this scale and suicidal ideation, suggesting a protective factor for suicide attempt. However, this would not be the case for individuals with a history of previous suicide attempts, especially adolescents, and there would not be any direct association with suicide[13],[21]. While not overly relevant for primary care settings, high scores for these six groups of variables (especially survival and coping beliefs, and moral objections to suicide) may moderate suicide risk factors (through a buffering effect), and correlate with resilience.

The three-part Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (ITS) has recently been promoted for use in predicting suicide risk. This theory explains / evaluates risk for suicide based on three fundamental areas: affection / behavior / cognition. One study used this theory to create the Suicidal Affect-Behavior-Cognition Scale (SABCS), which uses six self-administered questions to classify an individual as “non-suicidal” / “low suicide risk” / “moderate suicide risk” / “high suicide risk,” based on the answers he / she provides (i.e., without standardized scoring). Results from this scale are highly consistent with those from other scales such as the Beck Hopelessness Scale and the Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (ASIQ). While its theoretical foundations are interesting, it was validated in an online response study and has not been tested in any prospective studies[27].

Due to their quick application times and relatively consistent results in the 20 studies that were analyzed, four scales were reviewed for their potential use in the primary care setting: the SAD PERSONS scale, the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI), and the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).

1. SAD PERSONS scale

The name of this scale is an acronym for Sex, Age, Depression, Previous attempt, Excess alcohol or substance use, Rational thinking loss, Social supports lacking, Organized plan for suicide, No spouse, Sickness, which correspond to 10 risk factors for suicide (male sex, age < 20 or > 45 years, active diagnosis of depression, previous suicide attempt, alcohol / drug abuse, lack of rational thinking, inadequate social support, organized suicide plan, no partner, presence of health problems). For each risk factor present, one point is added, and the total score is used to determine patient management (0 to 2, “discharge and outpatient follow-up”; 3 to 4, “intensive outpatient follow-up; consider hospitalization; 5 to 6, hospitalization is suggested; 7 to 10, “forced hospitalization”)[14],[22].

The SAD PERSONS scale is used worldwide as a tool for evaluating suicide risk, and in Chile has been included in protocols for managing patients who have attempted suicide in various health centers[30],[31], but research shows it overestimates suicide risk and the need for hospitalization and does not predict suicide risk better than chance (sensitivity for current suicide / suicide attempt = 24 / 41%, future suicide / suicide attempt = 19.6 / 40% respectively). For example, Runeson’s systematic review of good methodological quality reports the scale’s sensitivity as 15%[15], and the Bolton study shows the scale’s profiles for moderate and severe suicide risk were significantly associated with low suicidal ideation, with half the cases presenting a low score on the scale[11],[19],[23].

2. Beck’s Hopelessness Scale

The Beck Hopelessness Scale is a self-applied instrument designed to generate dichotomous answers (True / False) to its 20 questions. Administering this scale takes 20 to 30 minutes. A score ≥ 9 indicates a considerable degree of hopelessness (negative expectation of the future), which would correlate with suicidal ideation. While hopelessness is linked to severe depression in current mental health practice, its value as a predictor of suicide is not evident in the literature[12],[14],[17],[22]. A meta-analysis shows the scale has low predictive values for suicide, with sensitivity of 29 to 54% and specificity of 60 to 84% (positive likelihood ratio: 1.55, 95% confidence interval: 1.31 to 1.83, and negative positive ratio: 0.45, 95% confidence interval: 0.20 to 1.03)[11].

A good-quality systematic review shows the scale has 89% sensitivity (95% confidence interval: 78 to 95%) and 42% specificity (95% confidence interval: 40 to 43%), based on moderate-quality evidence[15]. The reviewers rely on the fact that the scale identifies potential high-risk groups rather than potential behavior (in his initial study (in 1990), Beck estimated the group that scored positive for the scale criteria had 11 times higher risk than those that did not). A study that followed patients with depression (unipolar or bipolar) for one year showed that severity of depression measured by Beck's Depression Inventory predicted suicide attempt, but Beck's Hopelessness Scale did not[32]. Various websites provide access to this scale[33].

3. Beck’s Scale for Suicide Ideation

The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation investigates severity of suicidal ideation through 19 questions scored from 0 and 3, for a total score of 0 to 38. Two additional questions (20 and 21) collect descriptive data. Administering this scale takes approximately 10 to 15 minutes scale and must be done by specialized personnel[5]. It has been used in adolescents, adults, inpatients, and outpatients. In Beck's initial study, only the hopelessness item (not the total score) correlated predictively to some degree of suicidal ideation. The scale does not have cutoff points for classifying patients as high risk, or as indicators for a specific intervention, but it does show ideation gradients. It has a high internal consistency (Cronbach's coefficient of 0.89 to 0.96 and an interim reliability of 0.83) and good correlation with the Beck's Hopelessness Scale and Hamilton's Rating Scale for Depression. Brown's 20-year follow-up prospective study shows this scale has a positive predictive value of 3% and a hazard ratio of 6.56 for a cutoff point ≥ 2 (i.e., those with scores ≥ 2 would have almost seven times greater risk of suicide ideation than those with a score < 2[11],[12],[16],[18],[22]. Various websites provide tools for applying this scale[34].

4. Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

This scale is designed to 1) assess severity of suicidal ideation and behavior in the past month in patients 12 years and older, and 2) link the degree of severity to the level of immediate support the person would need. It evaluates four main items: severity of suicide ideation (passive ideation / active ideation / intention without planning / with planning / with specific method / with the intention of executing it), intensity of the ideation, suicidal behavior, and degree of lethality of the attempt, assigning a specific score for each item. There are multiple versions of the scale, designed for various contexts (initial assessment in emergency services, screening for primary care, military institutions, control in patients with a history of suicide risk, and initial evaluation in schools, among others).

The creators of the scale, the Columbia Lighthouse Project team, provide different versions of the C-SSRS on their website, available for free download, by context (general use, health care, military, and schools); target population (adults & adolescents, very young children, and individuals with cognitive impairments); and language (English or Spanish)[35].

The Columbia scale is recognized for clinical use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) because it is easy to use, can be applied in all settings, and effective[36]. It was validated in a study that included three specific population groups: adolescents that had attempted suicide (N = 124), depressed adolescents under treatment (N = 312) and adults who presented to an emergency service for psychiatric reasons (N = 237). The study, which had good methodological quality, showed good convergent validity with respect to other scales and divergent validity in the areas of suicidal ideation and behavior in adults and adolescents. In group 1, it showed significant predictive capacity for suicide attempt during treatment (i.e., a repeat attempt) (odds ratio: 1.45, 95% confidence interval: 1.07 to 1.98, p = 0.02) and at week 24 of the study (odds ratio: 1.34, 95% confidence interval: 1.05 to 1.70, p = 0.02), increasing the baseline risk by 45% and 34% respectively[25]. In addition to the complete version, a short (screening) version is available for use in primary care. Both versions are available both for patients who have never had suicidal ideation and for those who have a history of it[37],[38]. In addition to primary care use, the screening version has been applied extensively in health service networks where it has shown positive screening results ranging from 6.3% (in emergency services) to 2.1% (in outpatient clinics, and in hospitalization units)[39].

The C-SSRS has been linguistically validated in 45 languages, including Spanish, and has been psychometrically validated in the Spanish-speaking population[40],[41],[42]. It has a sensitivity of 94%, specificity of 97.9%, a positive predictive value 75.3% and a negative predictive value 94.7% for prediction of suicide attempt in adolescents and young Spanish-speaking adults[42]. The Greist study examined the ability of the scale to prospectively predict suicidal ideation and behavior in psychiatric and nonpsychiatric patients in 33 countries, using the baseline electronic C-SSRS (eC-SSRS). A meta-analysis of 54 406 eC-SSRS evaluations (8 837 baseline and 45 619 prospective) was conducted between 2009 and 2012.

This analysis shows that in psychiatric patients a positive eC-SSRS evaluation for only ideation predicts four times more risk of suicidal behavior than a negative result for both suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior (odds ratio: 4.66, 95% confidence interval: 2.6 to 8.3). In the same patients, those with a positive result for both ideation and suicidal behavior in their baseline eC-SSRS evaluation had nine times more risk of maintaining this behavior prospectively (odds ratio: 9.33, confidence interval 95%: 7.1 to 12.3). The scale is also predictive in nonpsychiatric patients, with those who have a positive baseline eC-SSRS result for suicidal behavior showing a 12-fold higher risk of maintaining it at the end of the follow-up period (odds ratio: 12.55, 95% confidence interval: 2.5 to 62.1). In those who present both suicidal ideation and behavior in their baseline assessment, the risk rises to 17 times higher (odds ratio: 17.11, 95% confidence interval: 3.4 to 85.5)[24].

Given these data, critics of the scale have asserted that it does not address the full spectrum of suicidal ideation or behavior, and has conceptual and psychometric errors[43]. Another disadvantage that has been cited is that its predictive capacity has only been tested 1) in adolescents, 2) for a brief period (9 months), and 3) electronically (online). No prospective studies have been conducted to validate it.

No version of the scale has been validated for Chile to date, but a revised version is being validated by Dr. Vania Martínez Nahuel, whom we contacted for this study[44].

The short version of the C-SSRS, which is used as a screening tool for primary health care, is limited to only one item—severity of suicidal ideation—through six direct questions classifying patients with suicidal ideation into three color-coded risk categories: red (high risk / requires immediate prevention measures); orange (moderate risk / requires evaluation by the mental health team as soon as possible for selection of precautionary measures); and yellow (slight risk / deferred referral of patients to mental health team) (Table 3). Although it is a simple tool—easy to apply and with logical theoretical thinking—the short version has not been validated prospectively, and the accuracy of the patient categorization and adequacy of the corresponding interventions are not clear. Although no prospective studies have validated this scale it is seen as a promising tool.

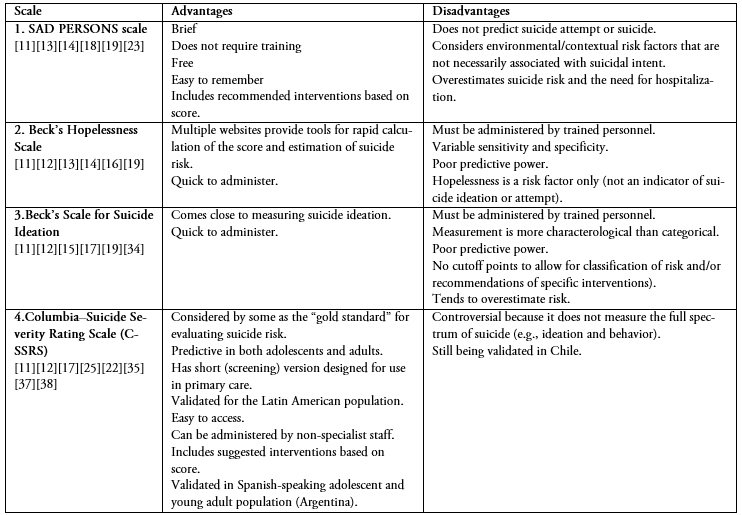

Table 4 lists the scales included in this review and summarizes their advantages and disadvantages.

Table 3. Screening version of the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).

WHO estimates that 800 000 people die worldwide each year from suicide—the second leading cause of death in those 15 to 29 years old. The impact of this number is magnified by the fact that for each person who commits suicide 10 to 20 others try to[6]. The impact of a suicide is profound—it is both a transgenerational family tragedy and proof that public policies have failed in the face of a preventable event.

Why try to identify individuals at risk of suicide? In its systematic review for 2004, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concludes that screening tools could help identify individuals at risk, and psychotherapy can reduce suicide attempts in those with high risk[20]. Thus, identifying individuals at risk is the first major step in preventing suicide. Positive feedback has also been shown to have a positive effect, with the exercise of identifying people at risk improving systematic use of mental health services, developing trust in doctor / patient relationships, and encouraging the clinician to use evidence-based interventions to reduce the risk[45].

But, how do we identify who is really at risk? We know that suicide is a complex problem involving multiple factors—experiential, psychosocial, and even cultural factors—as well as mental health status (e.g., history of a psychiatric illness such as major depressive disorder, bipolar depressive disorder, and/or substance use dependence, among others)[9].

A comprehensive patient evaluation that collects information on medical history, socio-demographic / biographical factors, psychiatric history, presence of suicidal ideation, family context, and support networks is essential. In the 20 studies we reviewed, some of the scales that were analyzed evaluated the same variables (previous suicidal behavior, thoughts and current plans of suicide, hopelessness, impulsiveness, self-control, and protective factors). However, this review found that studies that evaluate instruments used to assess suicide risk have limited methodological quality. For example, many of them measure composite outcomes (suicide and self-harm) and show low discrimination capacity for suicide, with sensitivities that do not surpass 90%, and specificity between 40 and 50%.

For the Beck Hopelessness Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, and Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation, positive predictive values (the proportion of individuals who will actually die by suicide among those with a positive screening result) have been as low as 1, 2, and 3% respectively. In the Suicide Intent Scale, a positive predictive value of 17% has been seen, but only in those who have previously attempted suicide. For the Suicide Assessment Scale (SUAS) and the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale, the positive predictive values were 19% and 14% respectively (with the latter measure corresponding to 9-week follow-up)[46]. There is also consistent evidence that some scales are not useful in predicting suicide risk (e.g., the SAD PERSONS scale does not predict suicide risk better than chance).

How good are the scales to predict suicide risk then? Not very good. Therefore, we do not consider or recommend the use of a suicide risk assessment scale as a single tool, in accordance with the recommendations of the World Health Organization[6], the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)[7], and the US Preventive Services Task Force (US-PSTF)[8].

Another disadvantage of using scales as predictors of suicide risk is that the cognitive, affective, and behavioral factors that they measure do not interact with the modifiable or demographic risk factors of the patient (e.g., age, sex, axis I diagnoses). For example, Chile’s national suicide prevention program bases its evaluation of suicide risk on multiple, classic risk factors that contribute to patient risk[10]. If we integrate these risk factors with the assessment scales for screening, does detection improve? A meta-analysis of cohort studies found that of patients categorized as "high suicide risk" (based on a combination of demographic factors, and assessment scales,) only 5% (overall positive predictive value) died from this cause, and half of those who died from suicide were classified as "low suicide risk" using the same method. Hence, some authors completely reject the idea of stratifying the suicidal patient by risk[47].

Some interesting alternatives for assessment of suicide risk have been suggested, including one from Roos, who proposes a unique instrument—a neuropsychological evaluation that generates a suicide risk profile. Administering this assessment would undoubtedly require specialized personnel, and there is thus far insufficent research to validate it[11]. In his review Carter rejects the idea of stratifying patients based on the results of assessment scales and proposes exhaustive clinical evaluation (especially of modifiable risk factors) and aggressive treatment for specific subpopulations (such as people with borderline personality disorder) instead[14]. We believe this method is plausible in hospitals and outpatient centers with specialized health personnel but unrealistic for primary care practice.

The limitations of primary care are an ongoing issue for suicide risk assessment in this setting, where most people seeking care enter the health system—many with a high burden of psychiatric morbidity that is often associated with specific psychosocial contexts and traumatic, adverse life histories. One study shows a prevalence of 2 to 3% for suicidal ideation in people seeking care in primary settings in the past month[8]. These patients are evaluated by health personnel with diverse mental health competencies and abilities, a situation that raises the question of how effectively suicidal ideation in the primary care setting is being managed.

How do we address the gaps in this scenario? By considering suicide risk scales as 1) a means of identifying suicide risk factors and not as predictors of attempted suicide, 2) tools for developing therapeutic alliances, and communicating with patients who may have intense psychic pain that impedes their ability to express themselves clearly, 3) support for calibrating interventions, and in epidemiological research. The focus should be on identifying and treating modifiable factors that allow patients with suicidal behavior to negotiate a plan based on their own needs (for example, treating addictions, managing mood disorders with antidepressants, increasing the perception of family support, and strengthening protective factors that could moderate risk factors), as well as restricting access to lethal elements, increasing patient supervision, and referring the patient for support services when existing supervision is not sufficient[47]. There is a lack of studies showing how to evaluate individuals for suicide risk, beyond intuition, especially in the primary care setting, where for the most part this type of assessment has been limited. The question remains whether or not the wrong factors are being measured—and if the relevant factors are interacting with any discernable pattern.

Given these gaps, the focus and efforts in this area could be directed toward aspects of suicide prevention, such as the development of public, community, and social policies that could, collectively, improve mental health and quality of life.

Evidence indicates currently available suicide risk assessment scales have limited value and low effectiveness in predicting suicide or suicidal intent. Therefore, these tools are most useful for descriptive evaluations, such as those that focus on developing communication or improving relationships with the patient. We envision the increased use of new methods to fill current gaps, such as integrated risk factor modeling, cognition testing, and interventions in specific mental health populations, as a reliable, predictive, brief, standardized tool for assessing risk for this cause of death in the primary care setting remains to be found.

Author contributions

CA: Conceptualization, Investigacion, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing (original draft preparation), Writing (review and editing). CG: Conceptualization, Investigacion, Methodology, Supervision, Writing (original draft preparation). CC: Conceptualization, Investigacion, Methodology, Supervision, Writing (original draft preparation). BE: Conceptualization, Investigacion, Methodology, Supervision, Writing (original draft preparation).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the guidance and quick response of The Columbia Lighthouse Project team and the collaboration and cooperative spirit/enthusiasm of Dr. Vania Martínez Nahuel (Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Chile).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have completed the ICMJE Conflict of Interest declaration form, and declare that they have not received funding for the report; have no financial relationships with organizations that might have an interest in the published article in the last three years; and have no other relationships or activities that could influence the published article. Forms can be requested by contacting the author responsible or the editorial management of the Journal.

Funding

The authors declare that there were no external sources of funding.

Table 1. Summary of results reported by the non-systematic reviews.

Table 1. Summary of results reported by the non-systematic reviews.

Table 2. Summary of results reported by the systematic reviews.

Table 2. Summary of results reported by the systematic reviews.

Figure 1. Flowchart of article selection process.

Figure 1. Flowchart of article selection process.

Table 3. Screening version of the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).

Table 3. Screening version of the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).

Table 4. Suicide risk assessment scales that may be suitable for primary care settings: advantages and disadvantages.

Table 4. Suicide risk assessment scales that may be suitable for primary care settings: advantages and disadvantages.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

According to the World Health Organization, suicide has become a public health problem of global dimensions. Forty-five percent of suicide fatalities had consulted with a primary care doctor in the month preceding the event, but no suicide risk assessment had been conducted. Although suicide is an avoidable event, there is no standardized scale for assessment of suicide risk in the primary health care setting, where mental health care competencies vary and decisions are often guided by clinical judgment. A search and review of the best available evidence was carried out to identify scales for assessment of suicide risk for the nonspecialist doctor (i.e., ideally, brief, predictive, and validated). We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane, Epistemonikos, and Scholar Google. We also contacted national and international experts on the subject. We retrieved 3 092 documents, of which 2 097 were screened by abstract, resulting in 70 eligible articles. After screening by full text, 20 articles were selected from which four scales were ultimately extracted and analyzed. Our review concludes that there are no suicide risk assessment scales accurate and predictive enough to justify interventions based on their results. Positive predictive values range from 1 to 19%. Of the patients classified as "high risk," only 5% will die by suicide. Half of the patients who commit suicide come from "low-risk" groups. We also discuss 1) the importance of evaluating a patient with suicidal behavior according to socio-demographic variables, history of mental health problems, and stratification within a scale, and 2) possible initial actions in the challenging context of primary care.

Autores:

Carolina Abarca[1,2], Cecilia Gheza[2], Constanza Coda[2], Bernardita Elicer[2]

Autores:

Carolina Abarca[1,2], Cecilia Gheza[2], Constanza Coda[2], Bernardita Elicer[2]

Citación:

Abarca C, Gheza C, Coda C, Elicer B.

Literature review to identify standardized scales for assessing adult suicide risk in the primary health care setting.

Fecha de envío: 27/6/2018

Fecha de aceptación: 30/8/2018

Fecha de publicación: 20/9/2018

Origen: no solicitado

Tipo de revisión: con revisión por cinco pares revisores externos, a doble ciego

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Prevención del suicidio un instrumento para trabajadores de Atención Primaria de Salud. Trastornos Mentales y Cerebrales Departamento de Salud Mental y Toxicomanías. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Ginebra. 2000. Disponible en [on line]. | Link |

Prevención del suicidio un instrumento para trabajadores de Atención Primaria de Salud. Trastornos Mentales y Cerebrales Departamento de Salud Mental y Toxicomanías. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Ginebra. 2000. Disponible en [on line]. | Link | Departamento de estadísticas e información en Salud (DEIS). Defunciones y mortalidad por causas. Chile. [on line]. | Link |

Departamento de estadísticas e información en Salud (DEIS). Defunciones y mortalidad por causas. Chile. [on line]. | Link | Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, Beck A, Waitzfelder BE, Rossom R, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med. 2014 Jun;29(6):870-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, Beck A, Waitzfelder BE, Rossom R, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med. 2014 Jun;29(6):870-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Links PS, Hoffman B. Preventing suicidal behaviour in a general hospital psychiatric service: priorities for programming. Can J Psychiatry. 2005 Jul;50(8):490-6.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Links PS, Hoffman B. Preventing suicidal behaviour in a general hospital psychiatric service: priorities for programming. Can J Psychiatry. 2005 Jul;50(8):490-6.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Rangel-Garzón C, Suárez MF, Escobar F. Escalas de evaluación de riesgo suicida en atención primaria.Revista de la Facultad de Medicina. 2015;63(4):707-716. | Link |

Rangel-Garzón C, Suárez MF, Escobar F. Escalas de evaluación de riesgo suicida en atención primaria.Revista de la Facultad de Medicina. 2015;63(4):707-716. | Link | National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Self-Harm: Longer-Term Management. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society; 2012. | PubMed |

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Self-Harm: Longer-Term Management. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society; 2012. | PubMed | Gaynes BN, West SL, Ford CA, Frame P, Klein J, Lohr KN. Screening for suicide risk in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. nn Intern Med. 2004 May 18;140(10):822-35. | PubMed |

Gaynes BN, West SL, Ford CA, Frame P, Klein J, Lohr KN. Screening for suicide risk in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. nn Intern Med. 2004 May 18;140(10):822-35. | PubMed | American Psychiatric Association. Guía de consulta de los criterios diagnósticos del DSM-5. DSM Library. [on line]. | Link |

American Psychiatric Association. Guía de consulta de los criterios diagnósticos del DSM-5. DSM Library. [on line]. | Link | Departamento de Salud Mental, División de Prevención y control de Enfermedades, Subsecretaría de Salud Pública, Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno de Chile. Programa Nacional de Prevención del Suicidio: Orientaciones para su implementación. 2013. [on line]. | Link |

Departamento de Salud Mental, División de Prevención y control de Enfermedades, Subsecretaría de Salud Pública, Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno de Chile. Programa Nacional de Prevención del Suicidio: Orientaciones para su implementación. 2013. [on line]. | Link | Roos L, Sareen J, Bolton J. Suicide risk assessment tools, predictive validity findings and utility today: time for a revamp? Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3(5):483-495. | Link |

Roos L, Sareen J, Bolton J. Suicide risk assessment tools, predictive validity findings and utility today: time for a revamp? Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3(5):483-495. | Link | Lotito M, Cook E. A review of suicide risk assessment instruments and approaches. Ment Health Clin. 2015;5(5):216-23. | CrossRef |

Lotito M, Cook E. A review of suicide risk assessment instruments and approaches. Ment Health Clin. 2015;5(5):216-23. | CrossRef | Hourani L, Jones D, Kennedy K, Hirsch K. Update on suicide assessment and instruments and methodologies. Naval health research center. Report No. 99-31. | Link |

Hourani L, Jones D, Kennedy K, Hirsch K. Update on suicide assessment and instruments and methodologies. Naval health research center. Report No. 99-31. | Link | Carter G, Milner A, McGill K, Pirkis J, Kapur N, Spittal MJ. Predicting suicidal behaviours using clinical instruments: systematic review and meta-analysis of positive redictive values for risk scales. Br J Psychiatry. 2017 Jun;210(6):387-395. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Carter G, Milner A, McGill K, Pirkis J, Kapur N, Spittal MJ. Predicting suicidal behaviours using clinical instruments: systematic review and meta-analysis of positive redictive values for risk scales. Br J Psychiatry. 2017 Jun;210(6):387-395. | CrossRef | PubMed | Runeson B, Odeberg J, Pettersson A, Edbom T, Jildevik Adamsson I, Waern M. Instruments for the assessment of suicide risk: A systematic review evaluating the certainty of the evidence. PLoS One. 2017 Jul 19;12(7):e0180292. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Runeson B, Odeberg J, Pettersson A, Edbom T, Jildevik Adamsson I, Waern M. Instruments for the assessment of suicide risk: A systematic review evaluating the certainty of the evidence. PLoS One. 2017 Jul 19;12(7):e0180292. | CrossRef | PubMed | Batterham PJ, Ftanou M, Pirkis J, Brewer JL, Mackinnon AJ, Beautrais A, et al. A systematic review and evaluation of measures for suicidal ideation and behaviors in population-based research. Psychol Assess. 2015 Jun;27(2):501-512. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Batterham PJ, Ftanou M, Pirkis J, Brewer JL, Mackinnon AJ, Beautrais A, et al. A systematic review and evaluation of measures for suicidal ideation and behaviors in population-based research. Psychol Assess. 2015 Jun;27(2):501-512. | CrossRef | PubMed | McMillan D, Gilbody S, Beresford E, Neilly L. Can we predict suicide and non-fatal self-harm with the Beck Hopelessness Scale? A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2007 Jun;37(6):769-78. | PubMed |

McMillan D, Gilbody S, Beresford E, Neilly L. Can we predict suicide and non-fatal self-harm with the Beck Hopelessness Scale? A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2007 Jun;37(6):769-78. | PubMed | Ghasemi P, Shaghaghi A, Allahverdipour H. Measurement Scales of Suicidal Ideation and Attitudes: A Systematic Review Article. Health Promot Perspect. 2015 Oct 25;5(3):156-68. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ghasemi P, Shaghaghi A, Allahverdipour H. Measurement Scales of Suicidal Ideation and Attitudes: A Systematic Review Article. Health Promot Perspect. 2015 Oct 25;5(3):156-68. | CrossRef | PubMed | Warden S, Spiwak R, Sareen J, Bolton JM. The SAD PERSONS scale for suicide risk assessment: a systematic review. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18(4):313-26. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Warden S, Spiwak R, Sareen J, Bolton JM. The SAD PERSONS scale for suicide risk assessment: a systematic review. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18(4):313-26. | CrossRef | PubMed | O'Connor E, Gaynes BN, Burda BU, Soh C, Whitlock EP. Screening for and treatment of suicide risk relevant to primary care: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013 May 21;158(10):741-54. | CrossRef | PubMed |

O'Connor E, Gaynes BN, Burda BU, Soh C, Whitlock EP. Screening for and treatment of suicide risk relevant to primary care: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013 May 21;158(10):741-54. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bakhiyi CL, Calati R, Guillaume S, Courtet P. Do reasons for living protect against suicidal thoughts and behaviors? A systematic review of the literature. J Psychiatr Res. 2016 Jun;77:92-108. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bakhiyi CL, Calati R, Guillaume S, Courtet P. Do reasons for living protect against suicidal thoughts and behaviors? A systematic review of the literature. J Psychiatr Res. 2016 Jun;77:92-108. | CrossRef | PubMed | Cochrane-Brink KA, Lofchy JS, Sakinofsky I. Clinical rating scales in suicide risk assessment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000 Nov-Dec;22(6):445-51. | PubMed |

Cochrane-Brink KA, Lofchy JS, Sakinofsky I. Clinical rating scales in suicide risk assessment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000 Nov-Dec;22(6):445-51. | PubMed | Bolton JM, Spiwak R, Sareen J. Predicting suicide attempts with the SAD PERSONS scale: a longitudinal analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012 Jun;73(6):e735-41. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bolton JM, Spiwak R, Sareen J. Predicting suicide attempts with the SAD PERSONS scale: a longitudinal analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012 Jun;73(6):e735-41. | CrossRef | PubMed | Greist JH, Mundt JC, Gwaltney CJ, Jefferson JW, Posner K. Predictive Value of Baseline Electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (eC-SSRS) Assessments for Identifying Risk of Prospective Reports of Suicidal Behavior During Research Participation. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014 Sep;11(9-10):23-31. | PubMed |

Greist JH, Mundt JC, Gwaltney CJ, Jefferson JW, Posner K. Predictive Value of Baseline Electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (eC-SSRS) Assessments for Identifying Risk of Prospective Reports of Suicidal Behavior During Research Participation. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014 Sep;11(9-10):23-31. | PubMed | Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011 Dec;168(12):1266-77. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011 Dec;168(12):1266-77. | CrossRef | PubMed | Niméus A, Alsén M, Träskman-Bendz L. The suicide assessment scale: an instrument assessing suicide risk of suicide attempters. Eur Psychiatry. 2000 Nov;15(7):416-23. | PubMed |

Niméus A, Alsén M, Träskman-Bendz L. The suicide assessment scale: an instrument assessing suicide risk of suicide attempters. Eur Psychiatry. 2000 Nov;15(7):416-23. | PubMed | Harris KM, Syu JJ, Lello OD, Chew YL, Willcox CH, Ho RH. The ABC's of Suicide Risk Assessment: Applying a Tripartite Approach to Individual Evaluations. PLoS One. 2015 Jun 1;10(6):e0127442. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Harris KM, Syu JJ, Lello OD, Chew YL, Willcox CH, Ho RH. The ABC's of Suicide Risk Assessment: Applying a Tripartite Approach to Individual Evaluations. PLoS One. 2015 Jun 1;10(6):e0127442. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wu CY, Lee JI, Lee MB, Liao SC, Chang CM, Chen HC, et al. Predictive validity of a five-item symptom checklist to screen psychiatric morbidity and suicide ideation in general population and psychiatric settings. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016 Jun;115(6):395-403. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wu CY, Lee JI, Lee MB, Liao SC, Chang CM, Chen HC, et al. Predictive validity of a five-item symptom checklist to screen psychiatric morbidity and suicide ideation in general population and psychiatric settings. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016 Jun;115(6):395-403. | CrossRef | PubMed | Green KL, Brown GK, Jager-Hyman S, Cha J, Steer RA, Beck AT. The Predictive Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory Suicide Item. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;76(12):1683-6.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Green KL, Brown GK, Jager-Hyman S, Cha J, Steer RA, Beck AT. The Predictive Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory Suicide Item. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;76(12):1683-6.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Ortiz M. Protocolo de ingreso, egreso y derivación de paciente con intento de suicidio. Hospital de Linares (Región del Maule, Chile). 2014. [on line]. | Link |

Ortiz M. Protocolo de ingreso, egreso y derivación de paciente con intento de suicidio. Hospital de Linares (Región del Maule, Chile). 2014. [on line]. | Link | Alarcón G. Protocolo Manejo del Intento Suicida en Servicios de Urgencia y Medicina. Hospital de Cauquenes (Región del Maule, Chile). 2012. [on line]. | Link |

Alarcón G. Protocolo Manejo del Intento Suicida en Servicios de Urgencia y Medicina. Hospital de Cauquenes (Región del Maule, Chile). 2012. [on line]. | Link | Oquendo MA, Galfalvy H, Russo S, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, Burke A, et al. Prospective study of clinical predictors of suicidal acts after a major depressive episode in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Aug;161(8):1433-41. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Oquendo MA, Galfalvy H, Russo S, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, Burke A, et al. Prospective study of clinical predictors of suicidal acts after a major depressive episode in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Aug;161(8):1433-41. | CrossRef | PubMed | Cálculo de riesgo de suicidio según Escala de Desesperanza de Beck. depresion.psicomag.com [on line]. | Link |

Cálculo de riesgo de suicidio según Escala de Desesperanza de Beck. depresion.psicomag.com [on line]. | Link | Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, Gould M, Stanley B, Brown G, et al. COLUMBIA-SUICIDE SEVERITY RATING SCALE (C-SSRS). cssrs.columbia.edu. [on line]. | Link |

Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, Gould M, Stanley B, Brown G, et al. COLUMBIA-SUICIDE SEVERITY RATING SCALE (C-SSRS). cssrs.columbia.edu. [on line]. | Link | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Guidance for Industry: Suicidal Ideation and Behavior: Prospective Assessment of Occurrence in Clinical Trials. August 2012, Clinical/Medical, Revision 1. [on line]. | Link |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Guidance for Industry: Suicidal Ideation and Behavior: Prospective Assessment of Occurrence in Clinical Trials. August 2012, Clinical/Medical, Revision 1. [on line]. | Link | Posner K., Brent D., Lucas C., Gould M., Stanley B., Brown G., et al. Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS) Baseline/Screening Version. 2008. The Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc.[on line]. | Link |

Posner K., Brent D., Lucas C., Gould M., Stanley B., Brown G., et al. Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS) Baseline/Screening Version. 2008. The Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc.[on line]. | Link | Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, Gould M, Stanley B, Brown G, et al. Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). Screener with triage for primary health settings. 2008. The Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene. [on line]. | Link |

Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, Gould M, Stanley B, Brown G, et al. Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). Screener with triage for primary health settings. 2008. The Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene. [on line]. | Link | Roaten K, Johnson C, Genzel R, Khan F, North CS. Development and Implementation of a Universal Suicide Risk Screening Program in a Safety-Net Hospital System. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018 Jan;44(1):4-11. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Roaten K, Johnson C, Genzel R, Khan F, North CS. Development and Implementation of a Universal Suicide Risk Screening Program in a Safety-Net Hospital System. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018 Jan;44(1):4-11. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gratalup G., Fernander N., Fuller D.S., Posner K. Translation of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale for Use in 33 Countries. International Society for CNS Clinical Trial Methodology, 9th Annual Scientific Meeting, Washington, D.C. 2013. [on line] | Link |

Gratalup G., Fernander N., Fuller D.S., Posner K. Translation of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale for Use in 33 Countries. International Society for CNS Clinical Trial Methodology, 9th Annual Scientific Meeting, Washington, D.C. 2013. [on line] | Link | Al-Halabí S, Sáiz PA, Burón P, Garrido M, Benabarre A, Jiménez E, et al. Validation of a Spanish version of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016 Jul-Sep;9(3):134-42. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Al-Halabí S, Sáiz PA, Burón P, Garrido M, Benabarre A, Jiménez E, et al. Validation of a Spanish version of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016 Jul-Sep;9(3):134-42. | CrossRef | PubMed | Serrani Azcurra D. Psychometric validation of the Columbia-Suicide Severity rating scale in Spanish-speaking adolescents. Colomb Med (Cali). 2017 Dec 30;48(4):174-182. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Serrani Azcurra D. Psychometric validation of the Columbia-Suicide Severity rating scale in Spanish-speaking adolescents. Colomb Med (Cali). 2017 Dec 30;48(4):174-182. | CrossRef | PubMed | Giddens JM, Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS): Has the "Gold Standard" Become a Liability?. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014 Sep;11(9-10):66-80. | PubMed |

Giddens JM, Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS): Has the "Gold Standard" Become a Liability?. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014 Sep;11(9-10):66-80. | PubMed | Posner K. Columbia escala de severidad suicida (C-SSRS) Versión para Chile – Pesquisa con puntos para Triage. Revisada para Chile por Dra. Vania Martínez. 2017. Datos no publicados.

Posner K. Columbia escala de severidad suicida (C-SSRS) Versión para Chile – Pesquisa con puntos para Triage. Revisada para Chile por Dra. Vania Martínez. 2017. Datos no publicados.  Green KL, Brown GK, Jager-Hyman S. Dr Green and Colleagues Reply. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Aug;77(8):1087-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Green KL, Brown GK, Jager-Hyman S. Dr Green and Colleagues Reply. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Aug;77(8):1087-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |