Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Este texto completo es la transcripción editada y revisada de una conferencia dictada en las Jornadas Latinoamericanas de Cáncer de Mama 2002, organizadas por la Escuela Latinoamericana de Mastología, Federación Latinoamericana de Mastología y Sociedad Chilena de Mastología.

Editor Científico: Dr. Hernando Paredes.

En las últimas décadas se ha obtenido un considerable progreso en el tratamiento del cáncer de mama. Los dos aspectos más relevantes en este avance han sido los siguientes:

La selección del tratamiento adyuvante para el carcinoma de mama en estadíos poco avanzados se basa en los Factores Pronósticos y Predictivos.

Los factores pronósticos son medidas o determinaciones disponibles en el momento del diagnóstico lo que, en ausencia de un tratamiento adyuvante sistémico, se asocia con una mayor frecuencia de recidivas y recurrencias tumorales así como con una mayor mortalidad. Los factores pronósticos ayudan a predecir la historia natural del tumor.

Los factores predictivos son mediciones que se asocian con la respuesta o ausencia de respuesta a un tratamiento específico.

Los factores pronósticos (1,2,3) habitualmente utilizados para seleccionar el tratamiento adyuvante sistémico en el carcinoma de mama son:

El tamaño tumoral es un predictor significativo de la recurrencia del carcinoma de mama. Cálculos del San Antonio Data Base señalan que el riesgo de recurrencia en el cáncer de mama con ganglios negativos aumenta con el tamaño tumoral creciente (5). El estudio comparativo del tamaño tumoral con otras variables, tales como grado histológico, p53, c-erb-B2, receptores de estrógenos y receptores de progesterona, ratificó el valor que el tamaño del tumor tiene por sí solo (6,7).

Los grados histológico y nuclear constituyen un factor pronóstico independiente en el cáncer de mama con ganglios negativos. La objeción que se les hace es que el sistema que establece los grados es, generalmente, subjetivo, con un factor limitante que es la ausencia de reproducibilidad y variabilidad entre los observadores.

Diversos factores expresan la proliferación celular y se pueden emplear para medir directamente la proliferación de las células tumorales. Ellos son Ki 67 (anticuerpo monoclonal específico para un antígeno nuclear expresado en células proliferentes), índice mitótico, fracción de fase S (por citometría de flujo) y el índice de marcación con timidina (8). La incorporación de timidina es un factor predictivo de la utilidad de la quimioterapia adyuvante; se ha comprobado una mayor sobrevida libre de enfermedad en pacientes tratadas con quimioterapia, quienes tenían tumores con alto índice proliferativo (13,14).

El estado menopáusico predice para la respuesta terapéutica a la ooforectomía (9). También el estado menopáusico predice para la eficacia de la quimioterapia adyuvante, pero no predice para la eficacia del tamoxifeno. El estado menopáusico se correlaciona, habitualmente, con el estado del receptor hormonal, pero ello no significa que permita presumir su positividad para seleccionar el tratamiento adyuvante sistémico.

De los nuevos marcadores biológicos y moleculares no existen aún estudios definitivos. Persisten dificultades técnicas que impiden validar el significado pronóstico de p53 y de cuantificar la pérdida de la función apoptótica celular (6,11,12).

En relación al valor de Her2neu como factor pronóstico, un metaanálisis reciente no logró avalar su uso como factor pronóstico puro (15). Hayes et al. (16) señalan que en pacientes no tratados, HER 2 tiene un valor, como factor pronóstico, entre débil y moderadamente fuerte. Además de ser HER 2 un blanco para tratamiento específico, es probablemente un predictor de respuesta a la quimioterapia y hormonoterapia. La sobreexpresión o amplificación de HER 2 se traduce en un menor beneficio con el uso de tamoxifeno adyuvante (16,17). Asimismo, los tumores que sobreexpresan HER 2 tienen mayor sensibilidad a la quimioterapia adyuvante con esquemas que contengan antraciclínicos (18). Andrulis et al. (19) han señalado que la amplificación de HER 2 en cáncer de mama con ganglios negativos es un factor pronóstico adverso e independiente para el riesgo de recurrencia.

La extensión de la microvascularización tumoral es un factor determinante para el desarrollo de posibles micrometástasis. Se han podido identificar marcadores anticipados de la invasión microvascular. Dentro de éstos tenemos el factor de crecimiento del endotelio vascular (VEGF), el activador del plasminógeno tipo urokinasa (uPA) y el activador del inhibidor tipo I del plasminógeno (PAI-1). Además de lo señalado previamente, la medida de la invasión linfática y vascular a nivel del tumor aporta información pronóstica significativa, tal como se señaló años atrás (20). El VEFG tiene un impacto pronóstico propio, que se puede incrementar significativamente combinándolo con uPA (21). La uPA, proteasa del tejido tumoral, y su inhibidor PAI-1 son marcadores biológicos asociados a las células tumorales, que participan en el proceso de invasión, migración celular, adhesión, angiogénesis y producción de metástasis. Ambas moléculas son poderosos factores pronósticos independientes de recurrencia tumoral y de muerte, en portadoras de cáncer de mama con ganglios negativos o positivos (22,23,24). Thomssen, en Alemania (25), evaluó prospectivamente ambos marcadores y señaló que el grado tumoral y uPA/PAI-1 son los factores pronósticos independientes más significativos en pacientes no tratadas con cáncer de mama con ganglios negativos.

La detección de micrometástasis ganglionares o en la médula ósea puede llegar a constituirse en otro factor de relevancia. En pacientes con ganglios negativos por microscopía convencional se han comprobado micrometástasis hasta en 10% a 20% de los casos, según diferentes series. Para convalidarlas se esperan resultados definitivos que surjan de ensayos prospectivos. Por su parte, la detección de micrometástasis en la médula ósea mantiene aún dudas conceptuales sobre si constituye o no un factor pronóstico independiente. Braun et al. (26) han señalado que la detección de micrometástasis en médula ósea tiene evidente correlación con la mala evolución clínica de las pacientes.

Por último, la aplicación de nuevos procedimientos tecnológicos, que dan lugar a los métodos conocidos como microarrays y proteomics, podrán aportar, en un futuro a mediano plazo, elementos pronósticos nuevos y más precisos de seleccionar el tratamiento adyuvante.

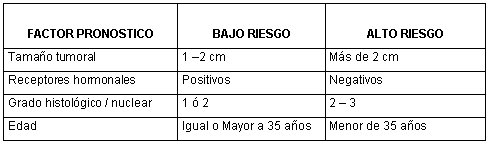

Las categorías de riesgo constituyen una manera útil de establecer en cada paciente el tratamiento adyuvante más adecuado. Estas categorías se correlacionan con la sobrevida que cada grupo alcanza al cabo de 5 y 10 años de seguimiento, luego de tratamiento locorregional, así como con las mejorías obtenidas con el tratamiento adyuvante sistémico. En la Séptima Conferencia Internacional sobre Tratamiento Adyuvante del Cáncer de Mama, St. Gallen 2001 (3), se establecieron dos categorías: bajo riesgo y alto riesgo. La presencia de metástasis ganglionares define el alto riesgo de las pacientes. Para las portadoras de cáncer de mama sin metástasis ganglionares, las características del tumor o de la paciente que se señalan permiten definir los subgrupos de bajo y alto riesgo (Tabla No. 1).

Tabla 1. Cáncer de Mama sin Metástasis Ganglionares. Grupos de Riesgo.

El NIH/NCI realizó la Conferencia de Consenso en el Tratamiento Adyuvante para el Cáncer de Mama en noviembre de 2000 (27). En ella se estableció que los factores pronósticos de valor crítico para determinar el riesgo de recurrencia son: edad; estado de los ganglios axilares; tamaño tumoral; tipo histológico / grado nuclear; receptores hormonales.

El objetivo del tratamiento hormonal adyuvante es el de impedir que las células del carcinoma de mama reciban el estímulo estrogénico. Esta situación ocurre en los tumores que presentan receptores hormonales positivos. El reducido subgrupo de pacientes que no tienen receptores de estrógenos, pero contienen el receptor de progesterona, también se beneficia del tratamiento hormonal adyuvante.

La deprivación estrogénica se puede obtener:

Múltiples ensayos clínicos han demostrado el beneficio del uso de tamoxifeno en las pacientes con cáncer de mama que expresen receptores hormonales positivos, en forma independiente de la edad, estado menopáusico, presencia o ausencia de metástasis ganglionares, tamaño del tumor y tratamiento con quimioterapia.

Las únicas excepciones que se señalan son: tumores muy pequeños, de 1 cm de diámetro o menos; premenopáusicas que quieran evitar los síntomas de la deprivación estrogénica; postmenopáusicas que tengan historia clínica de episodios de trombosis venosas y de tromboembolismo pulmonar.

El beneficio observado significó una prolongación de la sobrevida global, así como en la sobrevida libre de enfermedad con sustanciales reducciones en la posibilidad de recurrencia tumoral, de segundo cáncer primitivo de mama y descenso de la mortalidad hasta los 15 años de seguimiento. Estas conclusiones han sido señaladas por el EBCTCG (28,29,30) y recientemente, en la Séptima Reunión Internacional de St. Gallen (3).

En mujeres portadoras de cáncer de mama con receptores hormonales positivos se observó que el tamoxifeno reduce la muerte por cáncer de mama en 9% ± 1,5% a 15 años, sin aumentar significativamente las muertes producidas por causas diferentes al cáncer de mama.

Sólo las pacientes con tumores con receptores hormonales positivos se beneficiaron del tratamiento con tamoxifeno. Por ello, se recomienda no utilizar tamoxifeno en las portadoras de tumores con receptores hormonales negativos (31). Esa recomendación se ve reforzada por los resultados del estudio del NSABP B-23 (32) y del Intergrupo (33), los que señalaron la no reducción de la incidencia de cáncer de mama contralateral o mejoría en la sobrevida global en pacientes con tumores receptores hormonales negativos.

El metaanálisis del EBCTCG del año 2000 estableció la duración óptima del tratamiento adyuvante con tamoxifeno y demostró que 5 años de tratamiento (34,35,36), comparados con 1-2 años, produjeron un incremento adicional en la sobrevida de 3,2% ± 1%, a los 10 años, con sólo un aumento del 0,1% en los efectos colaterales graves, como el embolismo pulmonar y cáncer de endometrio.

Por tanto se debe recomendar de rutina la duración de 5 años de tratamiento. La prolongación del tratamiento con tamoxifeno adyuvante durante más de 5 años no ha revelado aún un claro beneficio terapéutico (37,38). Se continúa con la agrupación de pacientes en 2 ensayos clínicos importantes: aTTomb (39) y ATLAS (40). La dosis diaria clásicamente establecida es de 20 mg por día y por vía oral.

El valor de la quimioterapia asociada al tamoxifeno se evalúa en diversos estudios (41). En las pacientes postmenopáusicas, tanto los regímenes que contienen CMF en las dosis adecuadas (42) como los que contienen antraciclinas, tales como AC y FAC, mejoran la sobrevida libre de enfermedad (32,43), y probablemente la sobrevida global; se utilizan habitualmente en combinación con tamoxifeno en mujeres con receptores de estrógeno y de progesterona positivos.

Se ha demostrado que se debe administrar el tamoxifeno de manera secuencial y no concurrente con la quimioterapia (43,44,45), a continuación de esa adyuvancia.

Los inhibidores de la aromatasa de tercera generación, como anastrozole (Arimidex), letrozole (Femara) y exemestano (Aromasin), han demostrado su valor terapéutico en el cáncer de mama metastásico, en mujeres post menopáusicas. Esos resultados han determinado un notorio interés por utilizarlos en el tratamiento adyuvante, lo que ha dado origen a ensayos aleatorios, como ATAC, en el que se compara anastrazol (A) con tamoxifeno (T) y con la combinación de ambos (AT), en pacientes postmenopáusicas con receptores positivos o desconocidos. Se ha completado el grupo de pacientes, pero hay que aguardar los resultados con un seguimiento prolongado. Otros ensayos en curso comparan exemestano versus tamoxifeno, letrozole versus placebo después de 5 años de tamoxifeno adyuvante en pacientes postmenopáusicas, o tamoxifeno versus exemestano como primera opción en hormonoterapia adyuvante, o faslodex versus tamoxifeno.

La ablación ovárica es un tratamiento hormonal de alternativa para las pacientes premenopáusicas (46,47). En el metaanálisis del EBCTCG de 2000, (9,48,49), se señala que la ablación ovárica efectuada por diferentes procedimientos (cirugía, radioterapia o farmacológica) prolonga la sobrevida global absoluta, a 15 años, en 10,4% +/- 3,1%, en pacientes menores de 50 años, en las que se comparó la ablación ovárica con un grupo control sin tratamiento. En los ensayos clínicos en los que se cotejó la ablación ovárica con diversos regímenes de quimioterapia adyuvante convencional: CMF (50,51,52,53); FAC (54); FEC (55), no se evidenciaron diferencias en la sobrevida.

La asociación de quimioterapia y ablación ovárica versus quimioterapia no ha establecido aún una ventaja en la sobrevida a favor del tratamiento combinado (56). Por el momento, se debe considerar que la ablación ovárica es un tratamiento adyuvante aceptable en mujeres premenopáusicas con cáncer de mama hormonorrespondedor. Hacen falta nuevos estudios prospectivos que establezcan si la ablación ovárica es aditiva cuando se la combina con tamoxifeno o con quimioterapia.

El desarrollo de los análogos LHRH ha despertado creciente interés. La goserelina (Zoladex) en cáncer de mama metastásico mostró eficacia terapéutica comparable a la castración quirúrgica (57). La asociación con tamoxifeno más un análogo LHRH fue superior al análogo LHRH empleado solo (58). Esos resultados han motivado su uso como tratamiento adyuvante (59). El más empleado fue la goserelina (Zoladex). Se la ha comparado con tamoxifeno o goserelina más tamoxifeno o quimioterapia, o a ésta más tamoxifeno o más goserelina versus goserelina más tamoxifeno más quimioterapia (60).

El ensayo ZIPP (61), en premenopáusicas, observó, con 4,3 años de seguimiento, 20% menos de recurrencia en las pacientes que recibieron goserelina, independiente del uso concurrente de tamoxifeno o quimioterapia.

El estudio ECOG (56), en que se comparó CAF con CAF/goserelina con CAF/goserelina/tamoxifeno en premenopáusicas con ganglios positivos, demostró que la triple combinación fue superior en sobrevida libre de enfermedad, pero sin diferencia en la sobrevida global.

El Zoladex Early Breast Cancer Research Association (ZEBRA) (62), en premenopáusicas con ganglios positivos, comparó CMF con 2 años de goserelina. En este estudio, luego de 6 años de seguimiento, en el grupo de pacientes con receptores de estrógeno positivos, la goserelina fue equivalente a CMF en sobrevida libre de enfermedad; en cambio, en el subgrupo de receptores negativos, CMF fue superior a goserelina. La sobrevida global fue similar en ambos grupos.

Del conjunto de los resultados conocidos se puede estimar que la goserelina se asocia con una reducción significativa en las recurrencias; en mortalidad, el efecto es sólo marginal.

La quimioterapia es el tratamiento adyuvante de elección para la mayoría de las pacientes con receptores hormonales negativos. En el metaanálisis del EBCTCG de 1998 (63) y en su actualización de 2000 (48), todos los subgrupos de pacientes, ganglios negativos o ganglios positivos, pre o postmenopáusicas, con receptores hormonales negativos o positivos, se benefician significativamente en la sobrevida global, con rangos de 3% a 12%. El beneficio es mayor en las mujeres con mayor riesgo de recidiva.

Los datos del Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) (64) señalan que aquellos tumores menores de 1 cm de diámetro y con ganglios negativos presentan una sobrevida a 8 años de 95%, con pronóstico excelente e independiente del grado tumoral, por lo que no necesitarían quimioterapia adyuvante. Por el contrario, una revisión de protocolos del NSABP en pacientes con ganglios negativos, aleatorios, frente a un grupo control con quimioterapia adyuvante, demostró que los tumores de 1 cm de diámetro o menos, con receptores hormonales negativos, tenían peor pronóstico cuando no recibían quimioterapia adyuvante (sobrevida libre de enfermedad a 8 años: 90% versus 81%; p=0,06) (65).

En función de estos datos, la Conferencia de Consenso del NHI/NCI (27) , estima que esa terapia adyuvante tal vez no sea necesaria en tumores menores de 1 cm con ganglios negativos, con histología favorable (tipo tubular o mucinoso) y en pacientes mayores de 70 años.

En los restantes grupos de tumores, con diámetro mayor de 1 cm (27) o mayor de 2 cm (2,3), la reducción de la recidiva se comprueba en los 5 primeros años y persiste luego de ese lapso, pero sin incrementarse. La mejoría en la sobrevida global se constata en los 5 primeros años, pero con un beneficio adicional en los 6 años subsiguientes. Las reducciones significativas de las recurrencias y de la mortalidad se comprueban en pacientes tanto jóvenes como mayores, aunque la reducción es proporcionalmente menor en las pacientes de más edad.

En las menores de 50 años, el beneficio que se obtiene con la quimioterapia adyuvante es similar en quienes presentan receptores hormonales positivos o negativos. En el grupo etario de 50 a 69 años, se comprobó una significativa reducción en las recurrencias y en la mortalidad con quimioterapia adyuvante, tanto en portadoras de tumores receptores hormonales positivos como negativos (43,69,70,71,72). En ellas, el descenso en las recurrencias fue el doble en receptores hormonales negativos y la diferencia frente a las pacientes con receptores hormonales positivos fue significativa.

Con relación a las pacientes que presentaron metástasis en los ganglios, la reducción proporcional en recurrencias y mortalidad fue similar en las pacientes con receptores hormonales positivos y con receptores negativos. En pacientes menores de 50 años, el beneficio terapéutico fue mayor en quienes presentaron metástasis ganglionares (11%) contra 7% en quienes no las presentaron. En las mujeres de 50 a 69 años de edad, el beneficio alcanzado en la reducción de las recurrencias a 10 años fue parecido: 2% en ganglios negativos y 3% en ganglios positivos. En este mismo subgrupo, en cambio, la reducción de la mortalidad fue mayor en las pacientes con metástasis ganglionares.

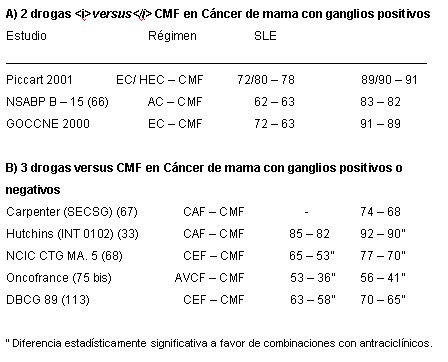

La comparación entre los regímenes de quimioterapia que contienen antraciclínicos y los de tipo CMF mostró una reducción proporcional de las recurrencias, de 12% y de 11% en la mortalidad a favor del uso de las antraciclinas (63). El riesgo absoluto de recidiva se redujo en 3,2% y el de mortalidad, en 2,7%. Al respecto, el estudio comparativo de la eficacia de combinaciones de antraciclínicos versus CMF en portadoras de cáncer de mama con metástasis ganglionares (3,32,33,66,68,69,75,76,77) da resultados equivalentes en regímenes antraciclínicos de 2 drogas, pero mejores en regímenes triples (Tabla No. 2).

Tabla 2. Analisis Comparativo de Regímenes con Antraciclinicos versus Cmf.

La importancia terapéutica de las dosis óptimas de la quimioterapia adyuvante, con miras a lograr el mejor beneficio terapéutico, se ha reiterado recientemente en Lohrisch et al. (78) y Basser (79).

En la conferencia de consenso de NHI/NCI (1) se ratifica una serie de aspectos íntimamente relacionados con la elección de la quimioterapia adyuvante, tales como la recomendación de elegir un régimen con dos o más drogas y no esquemas de monodroga. La duración que se propone es 4 a 6 ciclos de quimioterapia durante 3 a 6 meses (80). Los esquemas que se recomiendan son AC, CEF/ FEC, CAF/ FAC, A – CMF. Se debe considerar siempre el uso de tamoxifeno adyuvante en las pacientes con tumores con receptores hormonales positivos que tengan indicación de quimioterapia adyuvante.

En cuanto al concepto de intensidad de dosis o cantidad de droga suministrada por unidad de tiempo, está correlacionado con la respuesta al tratamiento (81). En el estudio CALGB 8541 se evaluó tres niveles de dosis y se demostró efectos significativos en términos de sobreviva sólo con los niveles intermedios y altos (82). Bonneterre et al. (83) evaluaron la eficacia de FEC con epirrubicina 50 mg/m2 versus 100 mg/m2, y se comprobó un efecto claramente significativo con la dosis mayor. El análisis minucioso de esta información permite afirmar que hay niveles críticos de dosificación de los citostáticos por debajo de los cuales éstos serían ineficaces.

El estudio CALGB 9344, en mujeres con metástasis ganglionares, asignó aleatoriamente a tres niveles diferentes de doxorrubicina: 60, 75 y 90 mg/m2 (84), y demostró ausencia de beneficio terapéutico con el aumento de dosis por sobre 60 mg/m2 de doxorrubicina. El estudio NSABP B-22 tampoco logró demostrar mayor acuvidad con el escalamiento de las dosis de ciclofosfamida (85). El estudio NSABP B-25 exploró el incremento en la intensidad de dosis y en la dosis acumulativa de ciclofosfamida, sin obtener beneficio terapéutico (86).

El concepto de densidad de dosis también se ha ensayado (87). Bonadonna et al. (88), en pacientes con más de tres ganglios con metástasis, compararon A y CMF en esquema alternante o secuencial. Al décimo año, esta última combinación, que era más intensa en cuanto a densidad de dosis, demostró que era superior.

La sobreexpresión de Her-2 neu (c-erb B-2) está señalada en estudios retrospectivos como predictor de respuesta a la quimioterapia con antraciclínicos (89), aunque estudios posteriores (90) no lograron confirmar esa correlación. Otros estudios clínicos aportan resultados parciales beneficiosos en relación al uso de antraciclínicos, en tumores con estas características, tales como el NSABP B – 11 (91), el CALGB 8082 (92) y el NSABP B – 15 (93). Si bien todos los estudios mencionados no tienen resultados con significación estadística, los autores estiman que hay una clara tendencia en el beneficio terapéutico que aporta la doxorrubicina en las pacientes con tumores HER 2 positivos.

Como contrapartida, la interacción entre la sobreexpresión de HER 2 y la quimioterapia con CMF demostró que el beneficio terapéutico se comprobó en pacientes HER 2 negativas (94,95).

El valor terapéutico del trastuzumab (Herceptin) en cáncer de mama metastásico HER 2 positivo ha sido la base de su incorporación en ensayos prospectivos para el tratamiento adyuvante en los tumores que sobreexpresan el gen, tales como son NSABP B-31 (96), BCIRG 006 (97), HERA (98), NCIC-CTG y E 2198, actualmente en marcha. Mientras no se disponga de sus resultados, el trastuzumab se deberá emplear en el contexto de estudios clínicos de investigación (99).

Si bien los taxanos son agentes tan activos como la doxorrubicina, en el tratamiento de la enfermedad metastásica, su papel en el tratamiento adyuvante no está definitivamente establecido (100). El ensayo clínico CALGB 9344 (84), comunicado en el Consenso NIH/NCI (101), comprobó que, a 52 meses de seguimiento, la mejoría en la sobreviva global informada anteriormente en las pacientes tratadas con AC/Paclitaxel versus AC, sólo tenía significación estadística en el límite de su valor (1,27,102). En el estudio NSABP B – 28 (103), que compara AC/Paclitaxel con AC, no se demostraron diferencias a 34 meses de seguimiento. El estudio del M D Anderson, (104) que compara FAC con Paclitaxel/FAC, tampoco comprobó diferencias a 36 meses de seguimiento. Hay a la fecha otros 12 estudios cooperativos en marcha, por lo que la incorporación de los taxanos a la quimioterapia adyuvante no se puede considerar aún una terapéutica estándar (106).

En pacientes con numerosos linfonodos axilares positivos, en las cuales hay un mal pronóstico con la quimioterapia adyuvante tradicional, algunos autores plantean el uso de esquemas que incluyan taxanos.

La quimioterapia de altas dosis, con rescate con células progenitoras, se encuentra también en fase de evaluación. La última comunicación de Peters no logró demostrar beneficio con su utilización (107); lo mismo ocurrió con una serie de otras publicaciones, incluso el estudio escandinavo SBG 9401 (100), el Dutch Nacional Study (109,110), el del Netherlands Cancer Institute (109,110) y el de M D Anderson (112), por lo que se debe estimar que es una tecnología absolutamente experimental.

Por último, debemos considerar en el desarrollo futuro de la quimioterapia adyuvante la incorporación de otros agentes citostáticos de alta efectividad en el terreno de la enfermedad metastásica, como la vinorelbina y otras, que permitirán ampliar las espectativas terapéuticas actuales en el manejo de esta enfermedad.

Los datos aportados por las sucesivas revisiones del EBCTCG (9,28,29,30,46,47,48,49,63), así como las recomendaciones terapéuticas propuestas en St. Gallen (2,3) y por la Conferencia de Consenso del NIH/NCI (1,27,102), permiten delinear las recomendaciones para los estadios I y II, incluyendo algunos casos del estadio III A:

1.- Cáncer de Mama con Metástasis Ganglionares

Para las pacientes receptores hormonales positivos, menores de 35 años, se recomienda el uso de tamoxifeno, además de la quimioterapia, dados los resultados poco satisfactorios obtenidos con el empleo único de quimioterapia.

El esquema CMF se puede utilizar cuando haya contraindicación para el uso de antraciclínicos. El empleo del esquema AC por 4 ciclos no es el tratamiento apropiado para el grupo con ganglios metastásicos. Las recomendaciones se centran en esquemas que incluyan antraciclínicos: FAC o CAF; FEC; A-CMF secuencial; AC-Paclitaxel secuencial. El número de ciclos variará entre 6 y 8, según la combinación elegida.

2. Cáncer de Mama sin Metástasis Ganglionares

Se debe definir, en primer lugar, las categorías de riesgo, de acuerdo a las recomendaciones más recientes (1,3):

Las recomendaciones terapéuticas para este grupo son:

Pacientes de bajo riesgo. Tumores con receptores hormonales positivos, pre o post menopáusicas: Tamoxifeno o nada.

Para las pacientes portadoras de tumores pequeños sin metástasis ganglionares y con histología favorable, tubular o mucinoso, no se recomienda adyuvancia.

Pacientes de alto riesgo.

Tumores con Receptores Hormonales Positivos

Premenopáusicas:

Postmenopáusicas:

Tumores con Receptores Hormonales Negativos pre o postmenopáusicas: quimioterapia

Los regímenes que contienen antraciclínicos son los de elección para el tratamiento adyuvante en pacientes de alto riesgo con ganglios negativos. Se debe tener presente que 4 ciclos de AC equivalen a 6 ciclos de CMF, como quimioterapia adyuvante en pacientes de alto riesgo sin metástasis ganglionares (32).

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Este texto completo es la transcripción editada y revisada de una conferencia dictada en las Jornadas Latinoamericanas de Cáncer de Mama 2002, organizadas por la Escuela Latinoamericana de Mastología, Federación Latinoamericana de Mastología y Sociedad Chilena de Mastología.

Editor Científico: Dr. Hernando Paredes.

Expositor:

Carlos Garbino[1]

Expositor:

Carlos Garbino[1]

Citación: Garbino C. Systemic adjuvant treatment of breast cancer: stages I and II. Medwave 2003 Sep;3(8):e3333 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2003.08.3333

Fecha de publicación: 1/9/2003

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Eifel P, Axelson JA, Costa J, Crowley J, Curran WJ Jr, Deshler A, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus Development Panel. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Adjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer, November 1-3, 2000. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001 Jul 4;93(13):979-89. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Eifel P, Axelson JA, Costa J, Crowley J, Curran WJ Jr, Deshler A, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus Development Panel. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Adjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer, November 1-3, 2000. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001 Jul 4;93(13):979-89. | CrossRef | PubMed | Goldhirsch A, Glick JH, Gelber RD, Senn HJ. Goldhiresh A, Glick JH, Gelber RD, Senn HJ : “Meeting highlights: International Consensus Panel on the Treatment of Primary Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Nov 4;90(21):1601-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Goldhirsch A, Glick JH, Gelber RD, Senn HJ. Goldhiresh A, Glick JH, Gelber RD, Senn HJ : “Meeting highlights: International Consensus Panel on the Treatment of Primary Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Nov 4;90(21):1601-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | St. Gallen 2001 News. Ed. Phillips Group Oncology Communications Co. PO Box 4024. Philadelphia, PA. USA, Decatron Digital Vision, Decatron Media AG | Link |

St. Gallen 2001 News. Ed. Phillips Group Oncology Communications Co. PO Box 4024. Philadelphia, PA. USA, Decatron Digital Vision, Decatron Media AG | Link | Fitzgibbons PL, Page DL, Weaver D, Thor AD, Allred DC, Clark GM, et al. Prognostic Factors in Breast Cancer: College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000 Jul;124(7):966-78. | PubMed |

Fitzgibbons PL, Page DL, Weaver D, Thor AD, Allred DC, Clark GM, et al. Prognostic Factors in Breast Cancer: College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000 Jul;124(7):966-78. | PubMed | Clark GM. Prognostic and predictive factors. En: Diseases of the breast. Philadelphia. PA. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2000, 489–514.

Clark GM. Prognostic and predictive factors. En: Diseases of the breast. Philadelphia. PA. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2000, 489–514.  Reed W, Hannisdal E, Boehler PJ, Gundersen S, Host H, Marthin J. The prognostic value of p53 and c – erb – B2 immunostaining is overrated for patients with lymph node negative breast carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in 613 patients with a follow -up of 14 – 30 years. Cancer. 2000 Feb 15;88(4):804-13. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Reed W, Hannisdal E, Boehler PJ, Gundersen S, Host H, Marthin J. The prognostic value of p53 and c – erb – B2 immunostaining is overrated for patients with lymph node negative breast carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in 613 patients with a follow -up of 14 – 30 years. Cancer. 2000 Feb 15;88(4):804-13. | CrossRef | PubMed | Volpi A, De Paola F, Nanni O, Granato AM, Bajorko P, Becciolini A, et al. Prognostic significance of biologic mar–Kers in node–negative breast cancer patients: a prospective study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000 Oct;63(3):181-92. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Volpi A, De Paola F, Nanni O, Granato AM, Bajorko P, Becciolini A, et al. Prognostic significance of biologic mar–Kers in node–negative breast cancer patients: a prospective study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000 Oct;63(3):181-92. | CrossRef | PubMed | Rudolph P, Olsson H, Bonatz G, Ratjen V, Bolte H, Baldetorp B, et al. Correlation between p53, c–erb–B2 and topoisomerasa II alpha expression, DNA ploidy, hormonal receptor status and proliferation in 356 node–negative breast carcinomas: prognostic implications. J Pathol. 1999 Jan;187(2):207-16. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Rudolph P, Olsson H, Bonatz G, Ratjen V, Bolte H, Baldetorp B, et al. Correlation between p53, c–erb–B2 and topoisomerasa II alpha expression, DNA ploidy, hormonal receptor status and proliferation in 356 node–negative breast carcinomas: prognostic implications. J Pathol. 1999 Jan;187(2):207-16. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kroman N, Jensen MB, Wohlfahrt J, Mouridsen HT, Andersen PK, Melbye M. Factors influencing the effect of age on prognosis in breast cancer: Population based study. BMJ. 2000 Feb 19;320(7233):474-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Kroman N, Jensen MB, Wohlfahrt J, Mouridsen HT, Andersen PK, Melbye M. Factors influencing the effect of age on prognosis in breast cancer: Population based study. BMJ. 2000 Feb 19;320(7233):474-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Ferrero JM, Ramaioli A, Formento JL, Francoual M, Etienne MC, Peyrottes I, et al. P53 determination alongside classical prognostic factors in node–negative breast cancer: an evaluation at more than 10 year follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2000 Apr;11(4):393-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ferrero JM, Ramaioli A, Formento JL, Francoual M, Etienne MC, Peyrottes I, et al. P53 determination alongside classical prognostic factors in node–negative breast cancer: an evaluation at more than 10 year follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2000 Apr;11(4):393-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Hamilton A, Piccart M. The contribution of molecular markers to the prediction of response in the treatment of breast cancer: a review of the literature on Her–2, p 53 and BCL–2. Ann Oncol. 2000 Jun;11(6):647-63. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hamilton A, Piccart M. The contribution of molecular markers to the prediction of response in the treatment of breast cancer: a review of the literature on Her–2, p 53 and BCL–2. Ann Oncol. 2000 Jun;11(6):647-63. | CrossRef | PubMed | Amadori D, Nanni O, Marangolo M, Pacini P, Ravaioli A, Rossi A, et al. Disease–free survival advantage of adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil in patients with node–negative, rapidly proliferating breast cancer: a randomized multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Sep;18(17):3125-34. | PubMed |

Amadori D, Nanni O, Marangolo M, Pacini P, Ravaioli A, Rossi A, et al. Disease–free survival advantage of adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil in patients with node–negative, rapidly proliferating breast cancer: a randomized multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Sep;18(17):3125-34. | PubMed | Jones S, Clark G, Koleszar S, Ethington G, Mennel R, Paulson S, et al. Low proliferative rate of invasive node- negative breast cancer predicts for a favourable outcome without adjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2001 Jan;1(4):310-4; discussion 315-7.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3816/CBC.2001.n.005 | PubMed |

Jones S, Clark G, Koleszar S, Ethington G, Mennel R, Paulson S, et al. Low proliferative rate of invasive node- negative breast cancer predicts for a favourable outcome without adjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2001 Jan;1(4):310-4; discussion 315-7.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3816/CBC.2001.n.005 | PubMed | Trock BJ, Yamauchi H, Brotzman M et al. c–erb–B2 as a prognostic factor in breast cancer (BC): a meta-analysis. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000; 19:7

Trock BJ, Yamauchi H, Brotzman M et al. c–erb–B2 as a prognostic factor in breast cancer (BC): a meta-analysis. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000; 19:7  Hayes DF, Yamauchi H, Stearns V et al.Should all breast cancers be tested for c–erb–B2? En: American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 36 th Annual Meeting. Alexandria, VA. USA. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2000, 257–265.

Hayes DF, Yamauchi H, Stearns V et al.Should all breast cancers be tested for c–erb–B2? En: American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 36 th Annual Meeting. Alexandria, VA. USA. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2000, 257–265.  Stål O, Borg A, Fernö M, Källström AC, Malmström P, Nordenskjöld B, et al. Erb B2 status and benefit from two or five years of adjuvant tamoxifen in post-menopausal early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2000 Dec;11(12):1545-50. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Stål O, Borg A, Fernö M, Källström AC, Malmström P, Nordenskjöld B, et al. Erb B2 status and benefit from two or five years of adjuvant tamoxifen in post-menopausal early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2000 Dec;11(12):1545-50. | CrossRef | PubMed | Paik S, Bryant J, Tan-Chiu E, Yothers G, Park C, Wickerham DL, et al. Her 2 and choice of adjuvant chemotherapy for invasive breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocol B-15. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000 Dec 20;92(24):1991-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Paik S, Bryant J, Tan-Chiu E, Yothers G, Park C, Wickerham DL, et al. Her 2 and choice of adjuvant chemotherapy for invasive breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocol B-15. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000 Dec 20;92(24):1991-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Andrulis IL, Bull SB, Blackstein ME, Sutherland D, Mak C, Sidlofsky S, et al. neu/erb B–2 amplification identifies a poor–prognosis group of women with node negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Apr;16(4):1340-9. | PubMed |

Andrulis IL, Bull SB, Blackstein ME, Sutherland D, Mak C, Sidlofsky S, et al. neu/erb B–2 amplification identifies a poor–prognosis group of women with node negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Apr;16(4):1340-9. | PubMed | Rosen PP, Groshen S, Kinne DW, Norton L. Factors influencing prognosis in node-negative breast carcinoma; analysis of 767 T1N0M0/ T2N0M0 patients with long-term follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 1993 Nov;11(11):2090-100. | PubMed |

Rosen PP, Groshen S, Kinne DW, Norton L. Factors influencing prognosis in node-negative breast carcinoma; analysis of 767 T1N0M0/ T2N0M0 patients with long-term follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 1993 Nov;11(11):2090-100. | PubMed | Eppenberger U, Kueng W, Schlaeppi JM, Roesel JL, Benz C, Mueller H, et al. Markers of tumor angiogenesis and proteolysis independently define high- and low-risk subsets of node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Sep;16(9):3129-36. | PubMed |

Eppenberger U, Kueng W, Schlaeppi JM, Roesel JL, Benz C, Mueller H, et al. Markers of tumor angiogenesis and proteolysis independently define high- and low-risk subsets of node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Sep;16(9):3129-36. | PubMed | Foekens JA, Peters HA, Look MP, Portengen H, Schmitt M, Kramer MD, et al. The urokinase system of plasminogen activation and prognosis in 2780 breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2000 Feb 1;60(3):636-43. | PubMed |

Foekens JA, Peters HA, Look MP, Portengen H, Schmitt M, Kramer MD, et al. The urokinase system of plasminogen activation and prognosis in 2780 breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2000 Feb 1;60(3):636-43. | PubMed | Harbeck N, Thomssen C, Berger U, Ulm K, Kates RE, Höfler H, et al. Invasion marker PAI–1 remains a strong prognostic factor after long-term follow-up both for primary breast cancer and following first relapse. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999 Mar;54(2):147-57.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Harbeck N, Thomssen C, Berger U, Ulm K, Kates RE, Höfler H, et al. Invasion marker PAI–1 remains a strong prognostic factor after long-term follow-up both for primary breast cancer and following first relapse. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999 Mar;54(2):147-57.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Prechtl A, Harbeck N, Thomssen C, Meisner C, Braun M, Untch M, et al. Tumor-biological factors uPA and PAI–1 as stratification criteria of a multicenter adjuvant chemotherapy trial in node-negative breast cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2000 Jan-Mar;15(1):73-8. | PubMed |

Prechtl A, Harbeck N, Thomssen C, Meisner C, Braun M, Untch M, et al. Tumor-biological factors uPA and PAI–1 as stratification criteria of a multicenter adjuvant chemotherapy trial in node-negative breast cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2000 Jan-Mar;15(1):73-8. | PubMed | Thomssen C, Prechtl A, Meisner C, et al. Efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in node-negative breast cancer patients with elevated uPA and PAI–1. tumor S67, Abstract 133.

Thomssen C, Prechtl A, Meisner C, et al. Efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in node-negative breast cancer patients with elevated uPA and PAI–1. tumor S67, Abstract 133.  Braun S, Pantel K, Müller P, Janni W, Hepp F, Kentenich CR, et al. Cytokeratin-positive cells in the bone marrow and survival of patients with stage I, II or III breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 24;342(8):525-33. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Braun S, Pantel K, Müller P, Janni W, Hepp F, Kentenich CR, et al. Cytokeratin-positive cells in the bone marrow and survival of patients with stage I, II or III breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 24;342(8):525-33. | CrossRef | PubMed | Abrams JS. Overview of the US consensus conference on adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. The Breast 2001; 10 (supplement 3): 139 – 146.

Abrams JS. Overview of the US consensus conference on adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. The Breast 2001; 10 (supplement 3): 139 – 146.  Effects of adjuvant tamoxifen and cytotoxic therapy on mortalitv early breast cancer: an overview of 61 randomized trials among 28.896 women. N Engl J Med. 1988 Dec 29;319(26):1681-92. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Effects of adjuvant tamoxifen and cytotoxic therapy on mortalitv early breast cancer: an overview of 61 randomized trials among 28.896 women. N Engl J Med. 1988 Dec 29;319(26):1681-92. | CrossRef | PubMed | Systemic treatment of early breast cancer by hormonal, cytotoxic or immune therapy: 133 randomized trials involving 31.000 recurrences and 24.000 deaths among 75.000 women. Lancet. 1992 Jan 11;339(8785):71-85. | PubMed |

Systemic treatment of early breast cancer by hormonal, cytotoxic or immune therapy: 133 randomized trials involving 31.000 recurrences and 24.000 deaths among 75.000 women. Lancet. 1992 Jan 11;339(8785):71-85. | PubMed | Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomized trials. Lancet. 1998 May 16;351(9114):1451-67. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomized trials. Lancet. 1998 May 16;351(9114):1451-67. | CrossRef | PubMed | Fisher B, Digman J, Wiensd S, Wolmark N, wickerham DL. Duration of tamoxifent (TAM) therapy for primary breast cancer: 5 years versus 10 years (NSAPP) P-14. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1996; 15:113 (Abstract).

Fisher B, Digman J, Wiensd S, Wolmark N, wickerham DL. Duration of tamoxifent (TAM) therapy for primary breast cancer: 5 years versus 10 years (NSAPP) P-14. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1996; 15:113 (Abstract).  Fischer B., Anderson s, Wolmark N, Tan-Chiu E. Chemoterapy with or without tamoxifen for patients with ER-negative breast cancer and negative nodes: Results from NSABP B-23. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000; 19:72. (Abstract).

Fischer B., Anderson s, Wolmark N, Tan-Chiu E. Chemoterapy with or without tamoxifen for patients with ER-negative breast cancer and negative nodes: Results from NSABP B-23. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000; 19:72. (Abstract).  Hutchins L, Green S, Ravdin P. CMF versus CAF with and without tamoxifen in high-risk node-negative breast cancer patients and a natural history fallow-up study in low-risk node-negative patients: first results of intergroup trial INT 0102. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998; 17:1. (Abstract).

Hutchins L, Green S, Ravdin P. CMF versus CAF with and without tamoxifen in high-risk node-negative breast cancer patients and a natural history fallow-up study in low-risk node-negative patients: first results of intergroup trial INT 0102. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998; 17:1. (Abstract).  Delozier T, Spielmann M, Mace-Lesech J et al.Short-term versus lifelong adjuvant tamoxifen in early breast cancer (EBC): A randomized trial (TAM-01). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 1289.

Delozier T, Spielmann M, Mace-Lesech J et al.Short-term versus lifelong adjuvant tamoxifen in early breast cancer (EBC): A randomized trial (TAM-01). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 1289.  Gallen M, Alonso MC, Ojeda B et al. “Randomized multicentre trial comparing two different time-spans of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy (ATT) in women with operable node positive breast cancer”, Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1994; 13: 76(abst).

Gallen M, Alonso MC, Ojeda B et al. “Randomized multicentre trial comparing two different time-spans of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy (ATT) in women with operable node positive breast cancer”, Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1994; 13: 76(abst).  Randomized trial of twa versus five years of adjuvant tamoxifen for postmenopausal early sta~e breast oancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996 Nov 6;88(21):1543-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Randomized trial of twa versus five years of adjuvant tamoxifen for postmenopausal early sta~e breast oancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996 Nov 6;88(21):1543-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Stewart HJ, Forrest AP, Everington D, McDonald CC, Dewar JA, Hawkins RA, et al. Randomized comparison of 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen with continuous therapy for operable breast. Br J Cancer. 1996 Jul;74(2):297-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Stewart HJ, Forrest AP, Everington D, McDonald CC, Dewar JA, Hawkins RA, et al. Randomized comparison of 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen with continuous therapy for operable breast. Br J Cancer. 1996 Jul;74(2):297-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Tormey DC, Gray R, Falkson HC. Postchemotherapy adjuvant tamoxifen beyond five years in patients with lymph node-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996 Dec 18;88(24):1828-33. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tormey DC, Gray R, Falkson HC. Postchemotherapy adjuvant tamoxifen beyond five years in patients with lymph node-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996 Dec 18;88(24):1828-33. | CrossRef | PubMed | CRC Trials Unit Birmingham. Adjuvant tamoxifen treatment offer more?(aTTom) Protocol. Birmingham: CRC Trials Unit.Clinical Research Block. Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

CRC Trials Unit Birmingham. Adjuvant tamoxifen treatment offer more?(aTTom) Protocol. Birmingham: CRC Trials Unit.Clinical Research Block. Queen Elizabeth Hospital.  Clinical Trial Service Unit, Radcliffe Infirmary, 0xford. Adjuvant tamoxifen longer against shorter (ATLAS). Protocol. April 1995. ATLAS Office,Clinical Trial Service Unit, Radcliffe lnfirmary,Oxford.(UK)

Clinical Trial Service Unit, Radcliffe Infirmary, 0xford. Adjuvant tamoxifen longer against shorter (ATLAS). Protocol. April 1995. ATLAS Office,Clinical Trial Service Unit, Radcliffe lnfirmary,Oxford.(UK)  Pritchard KI. Optimal endocrine therapy. The Breast 2001;10(Suppl 3):114—122

Pritchard KI. Optimal endocrine therapy. The Breast 2001;10(Suppl 3):114—122  Goldhirsch A, Coates AS, Colleoni M, Castiglione-Gertsoh M,Gelber RD. Adjuvant Chemoendocrine therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer:cyclophosphamide, metothrexate and fluorouracil dose and schedule may make a difference. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Apr;16(4):1358-62. | PubMed |

Goldhirsch A, Coates AS, Colleoni M, Castiglione-Gertsoh M,Gelber RD. Adjuvant Chemoendocrine therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer:cyclophosphamide, metothrexate and fluorouracil dose and schedule may make a difference. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Apr;16(4):1358-62. | PubMed | Albain K,Green S,Osborne K. et al.Tamoxifen (T) versus cyclophosphamide adriamycin and 5-Fu plus either concurrent or sequential T in postmenopausal receptor (positive) or node (positive) breast cancer: A Southwest Onoology Group phase III intergroup trial (SWOG-8814,INT-0100) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol l997;16:128a. (Abstract).

Albain K,Green S,Osborne K. et al.Tamoxifen (T) versus cyclophosphamide adriamycin and 5-Fu plus either concurrent or sequential T in postmenopausal receptor (positive) or node (positive) breast cancer: A Southwest Onoology Group phase III intergroup trial (SWOG-8814,INT-0100) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol l997;16:128a. (Abstract).  Osborne CK :Effects of estrogen and antiestrogens on cell proliferation. Implications for treatment of breast cancer. Endocrine treatment in breast and prostate cancer. OWSBORNE ck, ED. Kluwer, Boston, Massachussets, USA 1988: 11-129.

Osborne CK :Effects of estrogen and antiestrogens on cell proliferation. Implications for treatment of breast cancer. Endocrine treatment in breast and prostate cancer. OWSBORNE ck, ED. Kluwer, Boston, Massachussets, USA 1988: 11-129.  Ovarian ablation in early breast cancer: An overview of randomized. Trials. Lancet. 1996 Nov 2;348(9036):1189-96. | CrossRef |

Ovarian ablation in early breast cancer: An overview of randomized. Trials. Lancet. 1996 Nov 2;348(9036):1189-96. | CrossRef | Ovarian ablation for early breast cancer (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database Syst Rey 2000; 3:CD 000485.

Ovarian ablation for early breast cancer (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database Syst Rey 2000; 3:CD 000485.  Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EPCTCG) 2000 analysis overvlew results. Fifth Meeting of the Early Breast Canoer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. 2000 Oxford

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EPCTCG) 2000 analysis overvlew results. Fifth Meeting of the Early Breast Canoer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. 2000 Oxford  Peto R: Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Meeting. Oxford, October 2000.

Peto R: Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Meeting. Oxford, October 2000.  Adjuvant ovarian ablation CMF chemotherapy in premenopausal women with pathological stage II breast carcinoma: the Scottish trial. Lancet. 1993 May 22;341(8856):1293-8. | PubMed |

Adjuvant ovarian ablation CMF chemotherapy in premenopausal women with pathological stage II breast carcinoma: the Scottish trial. Lancet. 1993 May 22;341(8856):1293-8. | PubMed | Ejlertsen B,Dombernowsky P, Mouridsen H. et al. Comparable effect of ovarian (OA) and CNF chemotherapy in premenopausal hormonal receptor positive breast cancer patients (prp) Proc Am Sao Clin Oncol l999; 18: 66a (Abstract)

Ejlertsen B,Dombernowsky P, Mouridsen H. et al. Comparable effect of ovarian (OA) and CNF chemotherapy in premenopausal hormonal receptor positive breast cancer patients (prp) Proc Am Sao Clin Oncol l999; 18: 66a (Abstract)  Jonat W. Zoladex (Goserelin) vs CMF as adjuvant therapy in pre/perimenopausal early node-positive breast oancer:preliminary efficacy, COL,and PMD results from the ZEBRA Study. Breast Can Res Treat 2000;1:20 (Abstract)

Jonat W. Zoladex (Goserelin) vs CMF as adjuvant therapy in pre/perimenopausal early node-positive breast oancer:preliminary efficacy, COL,and PMD results from the ZEBRA Study. Breast Can Res Treat 2000;1:20 (Abstract)  Jakesz R, Gnant M,Hausmaninger H et al. Combination goserelin and tamoxifen is more effective than CMF in premenopausal patients with hormone-responsive tumors in a multicentre trial of the Austrian Breast Cancer Study Group (APCSG) Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999; 57:25.

Jakesz R, Gnant M,Hausmaninger H et al. Combination goserelin and tamoxifen is more effective than CMF in premenopausal patients with hormone-responsive tumors in a multicentre trial of the Austrian Breast Cancer Study Group (APCSG) Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999; 57:25.  Roche H,Mihura J,de Cafontan B et al. Castration and tamoxifen versus chemotherapy. (FAC) for premenopausal, node and receptor-positive breast cancer patients: a randomized trial with a 7 years median follow-up. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996;15:117 (Abstract)

Roche H,Mihura J,de Cafontan B et al. Castration and tamoxifen versus chemotherapy. (FAC) for premenopausal, node and receptor-positive breast cancer patients: a randomized trial with a 7 years median follow-up. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996;15:117 (Abstract)  Roche H,Keibrat P, Bonneterre J et al. Complete hormonal blockade versus chemotherapy in premenopausal early stage breast cancer patients (Pts) with positive hormone-reoeptors (HR+, ) and 1-3 node-positive (N+) tumor, results of the FASG 06 trial. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2000;19:72a (Abstract).

Roche H,Keibrat P, Bonneterre J et al. Complete hormonal blockade versus chemotherapy in premenopausal early stage breast cancer patients (Pts) with positive hormone-reoeptors (HR+, ) and 1-3 node-positive (N+) tumor, results of the FASG 06 trial. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2000;19:72a (Abstract).  Davidson N,O’Neill A,Vukov A et al.Effect of chemo-hormonal therapy in premenopausal node (positive) receptor (positive) breast cancer: an Eastern Cooperative 0ncology Group Phase III Intergroup Trial (E 5128,INT-0101)Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1999; l8:67a (Abstract).

Davidson N,O’Neill A,Vukov A et al.Effect of chemo-hormonal therapy in premenopausal node (positive) receptor (positive) breast cancer: an Eastern Cooperative 0ncology Group Phase III Intergroup Trial (E 5128,INT-0101)Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1999; l8:67a (Abstract).  Taylor CW, Green S, Dalton WS, Martino S, Rector D, Ingle JN, et al. Multicentre randomized clinical trial of goserelin versus surgical ovariectomy in premenopausal patients with receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: An Intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Mar;16(3):994-9. | PubMed |

Taylor CW, Green S, Dalton WS, Martino S, Rector D, Ingle JN, et al. Multicentre randomized clinical trial of goserelin versus surgical ovariectomy in premenopausal patients with receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: An Intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Mar;16(3):994-9. | PubMed | Boccardo F,Blamey R,Klijn J,Tominaga T,Duchateau L,Sylvester R. HRH-Agonist (LHRH-A) plus tamoxifen (TAM) versus LHRH-A alone in premenopausal women with advanced breast cancer (ABC) :Results of a meta-analysis of four trials#. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1999;18:110a (Abstract).

Boccardo F,Blamey R,Klijn J,Tominaga T,Duchateau L,Sylvester R. HRH-Agonist (LHRH-A) plus tamoxifen (TAM) versus LHRH-A alone in premenopausal women with advanced breast cancer (ABC) :Results of a meta-analysis of four trials#. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1999;18:110a (Abstract).  Kaufmann M,von Minckwitz G, for the German Adjuvant Breast Cancer Study Group (GABG). The emerging role of hormonal ablation as adjuvant therapy in node positive and node negative pre/perimenopausal patients. The Breast 2001; 10 (Suppl 3): 123-129.

Kaufmann M,von Minckwitz G, for the German Adjuvant Breast Cancer Study Group (GABG). The emerging role of hormonal ablation as adjuvant therapy in node positive and node negative pre/perimenopausal patients. The Breast 2001; 10 (Suppl 3): 123-129.  Randomized controlled trial of ovarian function supression plus tamoxifen versus the same endocrine the rapy plus chemotherapy: is chemotherapy necessary for premenopausal women with node-positive, endocrine-responsive breast cancer? First results of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 11-93. The Breast 2001;10 (Suppl 3): 130-138.

Randomized controlled trial of ovarian function supression plus tamoxifen versus the same endocrine the rapy plus chemotherapy: is chemotherapy necessary for premenopausal women with node-positive, endocrine-responsive breast cancer? First results of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 11-93. The Breast 2001;10 (Suppl 3): 130-138.  Rutqvist LE. Zoladex and tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy in premenopausal breast cancer: A raridomized trial by the Cancer Research Campaign (CRC) Breast Cancer Trials Group, the Stockholm Breast Cancer Study Group, the South-East Sweden Breast Group and the Gruppo Interdisciplinaire Valutazione Interventi in 0ncologia (GIVIO). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1999;18:67a (Abstract)

Rutqvist LE. Zoladex and tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy in premenopausal breast cancer: A raridomized trial by the Cancer Research Campaign (CRC) Breast Cancer Trials Group, the Stockholm Breast Cancer Study Group, the South-East Sweden Breast Group and the Gruppo Interdisciplinaire Valutazione Interventi in 0ncologia (GIVIO). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1999;18:67a (Abstract)  Zoladex (Goserelin) Vs CMF as adjuvant therapy in pre/perimenopausa1, node-positive,early breast cancer: Preliminary efficacy results from the ZEBRA study. Breast 2001;10:S30.

Zoladex (Goserelin) Vs CMF as adjuvant therapy in pre/perimenopausa1, node-positive,early breast cancer: Preliminary efficacy results from the ZEBRA study. Breast 2001;10:S30.  Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomized trials. Lancet. 1998 Sep 19;352(9132):930-42. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomized trials. Lancet. 1998 Sep 19;352(9132):930-42. | CrossRef | PubMed | Carter CL, Allen C,Henson DE. Relation of tumour size, lymph node status and survival in 24,750 breast cancer cases. Cancer. 1989 Jan 1;63(1):181-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Carter CL, Allen C,Henson DE. Relation of tumour size, lymph node status and survival in 24,750 breast cancer cases. Cancer. 1989 Jan 1;63(1):181-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Fisher B, Dignam J, Tan-Chiu E, Anderson S, Fisher ER, Wittliff JL, et al. Prognosis and treatment of patients with breast turnors of one centimeter or less and negative axillary nodes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001 Jan 17;93(2):112-20. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Fisher B, Dignam J, Tan-Chiu E, Anderson S, Fisher ER, Wittliff JL, et al. Prognosis and treatment of patients with breast turnors of one centimeter or less and negative axillary nodes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001 Jan 17;93(2):112-20. | CrossRef | PubMed | Fisher B, Brown AM, Dimitrov NV et al. Two months of doxorrubicin-cyclo phosphamide with and without interval reinduction therapy compared with 6 months of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil in node-positive breast cancer patients with tamoxifen-nonresponsive tumors: results from :the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-15 J Clin Oncol 1990 8:1483—1496. | PubMed |

Fisher B, Brown AM, Dimitrov NV et al. Two months of doxorrubicin-cyclo phosphamide with and without interval reinduction therapy compared with 6 months of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil in node-positive breast cancer patients with tamoxifen-nonresponsive tumors: results from :the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-15 J Clin Oncol 1990 8:1483—1496. | PubMed | Carpenter JT, Velwz-Garcia E, Aron BS et al. Five years results of a randomized comparison of cyclophospharnide, doxorrubicin and fluorouracil for node-positive breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1994;13:68 (Abstraet 20s).

Carpenter JT, Velwz-Garcia E, Aron BS et al. Five years results of a randomized comparison of cyclophospharnide, doxorrubicin and fluorouracil for node-positive breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1994;13:68 (Abstraet 20s).  Levine MN, Bramwell VH, Pritchard KI, Norris BD, Shepherd LE, Abu-Zahra H, et al. Randomized tríal of intensive cyclophosphamide, epirubicin and fluorouracil chemotherapy compared with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil in premenopausal wotnen with node positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Aug;16(8):2651-8. | PubMed |

Levine MN, Bramwell VH, Pritchard KI, Norris BD, Shepherd LE, Abu-Zahra H, et al. Randomized tríal of intensive cyclophosphamide, epirubicin and fluorouracil chemotherapy compared with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil in premenopausal wotnen with node positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Aug;16(8):2651-8. | PubMed | Fisher B, Redmond C, Legault-Poisson S, Dimitrov NV, Brown AM, Wickerham DL, et al. Postoperative chemotherapy and tamoxifen compared with tamoxifen alone in the treatment of positive-node breast cancer patients aged 50 years and. older with tumors responsive to tamoxifen: Results from the Nationa1 Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-16. J Clin Oncol. 1990 Jun;8(6):1005-18. | PubMed |

Fisher B, Redmond C, Legault-Poisson S, Dimitrov NV, Brown AM, Wickerham DL, et al. Postoperative chemotherapy and tamoxifen compared with tamoxifen alone in the treatment of positive-node breast cancer patients aged 50 years and. older with tumors responsive to tamoxifen: Results from the Nationa1 Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-16. J Clin Oncol. 1990 Jun;8(6):1005-18. | PubMed | International Breast Cancer Study Group. Effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy in combination with tamoxifen for node-positive postmenopausal treast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1997 Apr;15(4):1385-94 | PubMed |

International Breast Cancer Study Group. Effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy in combination with tamoxifen for node-positive postmenopausal treast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1997 Apr;15(4):1385-94 | PubMed | Crivellari D, Bonetti M, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Gelber RD, Rudenstam CM, Thürlimann B, et al. Burdens and benefits of adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil and tamoxifen for elderly patients with breast cancer. The International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial VII. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Apr;18(7):1412-22. | PubMed |

Crivellari D, Bonetti M, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Gelber RD, Rudenstam CM, Thürlimann B, et al. Burdens and benefits of adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil and tamoxifen for elderly patients with breast cancer. The International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial VII. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Apr;18(7):1412-22. | PubMed | Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, DeCillis A, Emir B, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen and cheinotherapy for lymph node-negative,estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997 Nov 19;89(22):1673-82. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, DeCillis A, Emir B, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen and cheinotherapy for lymph node-negative,estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997 Nov 19;89(22):1673-82. | CrossRef | PubMed | Pritchard KI, Paterson AH, Fine S, Paul NA, Zee B, Shepherd LE, et al. Randomized trial of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil chemotherapy added to tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy in postmenopausal women with node positive, estrogen and/or progesterone receptor positive breast cancer: A report of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Breast Cancer Site Group. J Clin Oncol. 1997 Jun;15(6):2302-11. | PubMed |

Pritchard KI, Paterson AH, Fine S, Paul NA, Zee B, Shepherd LE, et al. Randomized trial of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil chemotherapy added to tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy in postmenopausal women with node positive, estrogen and/or progesterone receptor positive breast cancer: A report of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Breast Cancer Site Group. J Clin Oncol. 1997 Jun;15(6):2302-11. | PubMed | Castiglione-Gertsch M, Price KN, Nasi ML, et al. Is the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy always necessary in node negative postmenopausal breast cancer patients who receive tamoxifen? First results of IBCSG trial IX. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2000; 19: 73a (abst.281).

Castiglione-Gertsch M, Price KN, Nasi ML, et al. Is the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy always necessary in node negative postmenopausal breast cancer patients who receive tamoxifen? First results of IBCSG trial IX. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2000; 19: 73a (abst.281).  Fisher B, Redmond C, Wickerham DL, Bowman D, Schipper H, Wolmark N, et al. Doxorubicin containing regimens for the treatment of Stage II breast cancer. The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project experience. J Clin Oncol. 1989 May;7(5):572-82. | PubMed |

Fisher B, Redmond C, Wickerham DL, Bowman D, Schipper H, Wolmark N, et al. Doxorubicin containing regimens for the treatment of Stage II breast cancer. The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project experience. J Clin Oncol. 1989 May;7(5):572-82. | PubMed | Misset JL, di Palma M, Delgado M, Plagne R, Chollet P, Fumoleau P, et al. Adjuvant treatment of node-positive breast cancer with oyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, fluorouracil and vincristine versus cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil. Final report after a 16 year median follow-up duration. J Clin Oncol. 1996 Apr;14(4):1136-45. | PubMed |

Misset JL, di Palma M, Delgado M, Plagne R, Chollet P, Fumoleau P, et al. Adjuvant treatment of node-positive breast cancer with oyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, fluorouracil and vincristine versus cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil. Final report after a 16 year median follow-up duration. J Clin Oncol. 1996 Apr;14(4):1136-45. | PubMed | Tormey DC, Gray R, Abeloff MD, Roseman DL, Gilchrist KW, Barylak EJ, et al. Adjuvant therapy with a doxorubicin regimen and long-term tamoxifen in premenopausal breast cancer patients. An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 1992 Dec;10(12):1848-56. | PubMed |

Tormey DC, Gray R, Abeloff MD, Roseman DL, Gilchrist KW, Barylak EJ, et al. Adjuvant therapy with a doxorubicin regimen and long-term tamoxifen in premenopausal breast cancer patients. An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 1992 Dec;10(12):1848-56. | PubMed | Coombes RC, Bliss JM, Wils J, Morvan F, Espié M, Amadori D, et al. Adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil versus fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy in premenopausal woman with axillary node-positive operable breast cancer: Results of a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1996 Jan;14(1):35-45. | PubMed |

Coombes RC, Bliss JM, Wils J, Morvan F, Espié M, Amadori D, et al. Adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil versus fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy in premenopausal woman with axillary node-positive operable breast cancer: Results of a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1996 Jan;14(1):35-45. | PubMed | Lohrisch C, Di Leo A, Piccart MJ. Optimal adjuvant cytotoxic therapy for breast cancer. The Breast 2001;10 (Suppl 3):106-113.

Lohrisch C, Di Leo A, Piccart MJ. Optimal adjuvant cytotoxic therapy for breast cancer. The Breast 2001;10 (Suppl 3):106-113.  Basser RL. Optimal dose of chemotherapy in adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. The Breast 2001; 10 (Suppl 3): 96—100.

Basser RL. Optimal dose of chemotherapy in adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. The Breast 2001; 10 (Suppl 3): 96—100.  Colleoni M,Gelber RD, Gelber S,Castiglione-Gertsoh M,Coates AS,Goldhirsch A: “How to improve timing and duration of adjuvant chemotherapy. The Breast 2001;10 (Suppl 3):101-105.

Colleoni M,Gelber RD, Gelber S,Castiglione-Gertsoh M,Coates AS,Goldhirsch A: “How to improve timing and duration of adjuvant chemotherapy. The Breast 2001;10 (Suppl 3):101-105.  Hryniuk W, Levine MN. Analysis of dose Intensity for adjuvant chemotherapy trials in Stage II breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986 Aug;4(8):1162-70. | PubMed |

Hryniuk W, Levine MN. Analysis of dose Intensity for adjuvant chemotherapy trials in Stage II breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986 Aug;4(8):1162-70. | PubMed | Budman DR, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, Henderson IC, Wood WC, Weiss RB, et al. Dose and dose intensity as determinants of outcome in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Aug 19;90(16):1205-11. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Budman DR, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, Henderson IC, Wood WC, Weiss RB, et al. Dose and dose intensity as determinants of outcome in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Aug 19;90(16):1205-11. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bonneterre J, Roche H,Bremond A et al. Results of a randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with FEC 50 vs FEC 100 in high risk node-positive breast cancer patients. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998; 17:124a (abst 473).

Bonneterre J, Roche H,Bremond A et al. Results of a randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with FEC 50 vs FEC 100 in high risk node-positive breast cancer patients. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998; 17:124a (abst 473).  Henderson IC, Beny D, Demetri G et al. Improved disease-free and overall sur vival from the addition of sequential paclitaxel but not from the escalation of doxorubicin dose level in the adjuvant chemotherapy of patients with node positive primary breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998; 17:101a (abst 390ª)

Henderson IC, Beny D, Demetri G et al. Improved disease-free and overall sur vival from the addition of sequential paclitaxel but not from the escalation of doxorubicin dose level in the adjuvant chemotherapy of patients with node positive primary breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998; 17:101a (abst 390ª)  Fisher B, Anderson S, Wickerham DL, DeCillis A, Dimitrov N, Mamounas E, et al. Increased intensification and total dose of cyclophosphamide in a doxorubicin-cyclophosphamicle regimen for the treatment of primary breast cancer. Findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-22. J Clin Oncol. 1997 May;15(5):1858-69. | PubMed |

Fisher B, Anderson S, Wickerham DL, DeCillis A, Dimitrov N, Mamounas E, et al. Increased intensification and total dose of cyclophosphamide in a doxorubicin-cyclophosphamicle regimen for the treatment of primary breast cancer. Findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-22. J Clin Oncol. 1997 May;15(5):1858-69. | PubMed | Fisher B, Anderson S, DeCillis A, Dimitrov N, Atkins JN, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Further evaluation of intensified and increased total dose of cyclophosphamide for the treatment of primary breast cancer: Findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-25. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Nov;17(11):3374-88. | PubMed |

Fisher B, Anderson S, DeCillis A, Dimitrov N, Atkins JN, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Further evaluation of intensified and increased total dose of cyclophosphamide for the treatment of primary breast cancer: Findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-25. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Nov;17(11):3374-88. | PubMed | Hudis C, Seidman A, Baselga J, Raptis G, Lebwohl D, Gilewski T, et al. Sequential dose-dense doxorubicin, paclitaxel and cyclophosphamide for resectable high-risk breast cancer: Feasibility and efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Jan;17(1):93-100. | PubMed |

Hudis C, Seidman A, Baselga J, Raptis G, Lebwohl D, Gilewski T, et al. Sequential dose-dense doxorubicin, paclitaxel and cyclophosphamide for resectable high-risk breast cancer: Feasibility and efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Jan;17(1):93-100. | PubMed | Bonadonna G,Zambetti M,Valagusa P. Sequential or alternating doxorubicin and CMF regimens in breast cancer with more than three positive nodes. Ten-years’ results. JAMA. 1995 Feb 15;273(7):542-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bonadonna G,Zambetti M,Valagusa P. Sequential or alternating doxorubicin and CMF regimens in breast cancer with more than three positive nodes. Ten-years’ results. JAMA. 1995 Feb 15;273(7):542-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Muss HB, Thor AD, Berry DA, Kute T, Liu ET, Koerner F, et al. c-erb B-2 expression and response to adjuvant chernotherapy in women with node-positive early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994 May 5;330(18):1260-6. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Muss HB, Thor AD, Berry DA, Kute T, Liu ET, Koerner F, et al. c-erb B-2 expression and response to adjuvant chernotherapy in women with node-positive early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994 May 5;330(18):1260-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | Thor AD, Berry DA, Budman DR, Muss HB, Kute T, Henderson IC, et al. erb B-2, p53 and efficacy of adjuvant therapy in lymph node positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Sep 16;90(18):1346-60. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Thor AD, Berry DA, Budman DR, Muss HB, Kute T, Henderson IC, et al. erb B-2, p53 and efficacy of adjuvant therapy in lymph node positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Sep 16;90(18):1346-60. | CrossRef | PubMed | Paik S, Bryant J, Park C, Fisher B, Tan-Chiu E, Hyams D, et al. erb B-2 and response to doxoruticin in pacients with axillary lymph node-positive, hormone receptor-negative breast cancer J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Sep 16;90(18):1361-70. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Paik S, Bryant J, Park C, Fisher B, Tan-Chiu E, Hyams D, et al. erb B-2 and response to doxoruticin in pacients with axillary lymph node-positive, hormone receptor-negative breast cancer J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Sep 16;90(18):1361-70. | CrossRef | PubMed | Berry DA, Thor A, Cirrincione C, et al. Scientific inference and predictions; multiplicities and convincing stories: A case study in breast cancer therapy En: Statistics 5, Oxford UK. Oxford University Press. 1996, p 45—67.

Berry DA, Thor A, Cirrincione C, et al. Scientific inference and predictions; multiplicities and convincing stories: A case study in breast cancer therapy En: Statistics 5, Oxford UK. Oxford University Press. 1996, p 45—67.  Paik S, Bryant J,Tan-Chiu E, et al. HER 2 and choice of adjuvant chemotherapy for invasive breast cancer. National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Powel Project Protocol B-15 J Nat Cancer Inst 2000;92: 1991-1998.

Paik S, Bryant J,Tan-Chiu E, et al. HER 2 and choice of adjuvant chemotherapy for invasive breast cancer. National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Powel Project Protocol B-15 J Nat Cancer Inst 2000;92: 1991-1998.  Gusterson BA, Gelber RD, Goldhirsch A, Price KN, Säve-Söderborgh J, Anbazhagan R, et al. Prognostic importance of c-erb B-2 expression in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992 Jul;10(7):1049-56. | PubMed |

Gusterson BA, Gelber RD, Goldhirsch A, Price KN, Säve-Söderborgh J, Anbazhagan R, et al. Prognostic importance of c-erb B-2 expression in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992 Jul;10(7):1049-56. | PubMed | Barnes DM, Smith S, Rubens RD. The relationship between outcome following adjuvant CMF and the presence of estrogen receptor and c-erb B-2 protein in 277 women with primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1997;46:65 (abst 257).

Barnes DM, Smith S, Rubens RD. The relationship between outcome following adjuvant CMF and the presence of estrogen receptor and c-erb B-2 protein in 277 women with primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1997;46:65 (abst 257).  Phase III randomized study of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel with or without trastuzuinab (Herceptin) in women with node positive breast cancer that overexpresses HER 2. National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-31.

Phase III randomized study of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel with or without trastuzuinab (Herceptin) in women with node positive breast cancer that overexpresses HER 2. National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-31.  BCIRG 006: A multicenter phase III randomized trial comparing docetaxel in combination with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (TAC) versus doxorubiciri and cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel and Herceptin (AC--TH) versus doce- taxel and platinum salt and Herceptin (TCH) in the treatment of node positive and high risk node negative adjuvant patients with operable breast cancer who overexpress HER 2 NEU. Breast Cancer International Research Group 006.

BCIRG 006: A multicenter phase III randomized trial comparing docetaxel in combination with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (TAC) versus doxorubiciri and cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel and Herceptin (AC--TH) versus doce- taxel and platinum salt and Herceptin (TCH) in the treatment of node positive and high risk node negative adjuvant patients with operable breast cancer who overexpress HER 2 NEU. Breast Cancer International Research Group 006.  Perez EA. Adjuvant anti-HER 2 monoclonal antibody therapy - ready for breast cancer? The Breast 2001; 10 (Suppl 3 ):161—163.

Perez EA. Adjuvant anti-HER 2 monoclonal antibody therapy - ready for breast cancer? The Breast 2001; 10 (Suppl 3 ):161—163.  Davidson NE,Wolff AC. The use of anthracyclines and taxanes for adjuvant therapy of breast cancer. The Breast 2001:10 (Suppl 3): 90-95.

Davidson NE,Wolff AC. The use of anthracyclines and taxanes for adjuvant therapy of breast cancer. The Breast 2001:10 (Suppl 3): 90-95.  Henderson IC: CALGB ria l9344NIH Dc an Adjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer 2000 ; Bethesda,MD.USA.

Henderson IC: CALGB ria l9344NIH Dc an Adjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer 2000 ; Bethesda,MD.USA.  Adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. NIH Consens Statement. 2000 Nov 1-3;17(4):1-35.

11512506

Adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. NIH Consens Statement. 2000 Nov 1-3;17(4):1-35.

11512506  Mamounas EF. Evaluating the use of paclitaxel following doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide in patients with breast cancer and positive axillary rodes NSABP B-28 protocol. NIH CDC on adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, 2000; Bethesda, MD.USA.

Mamounas EF. Evaluating the use of paclitaxel following doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide in patients with breast cancer and positive axillary rodes NSABP B-28 protocol. NIH CDC on adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, 2000; Bethesda, MD.USA.  Thomas E, Buzdar A, Theriault R et al. Role of paclitaxel in adjuvant therapy of operable breast cancer: Preliminary results of prospective randomized clinical trial. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;19:74 A (abst 285)

Thomas E, Buzdar A, Theriault R et al. Role of paclitaxel in adjuvant therapy of operable breast cancer: Preliminary results of prospective randomized clinical trial. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;19:74 A (abst 285)  BCIRG 001/TAX 316: A multicenter phase III randomized trial comparing docetaxel in combination with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (TAC) versus 5-Fluorouracil in combination with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (FAC) as adjuvant treatment of operable breast cancer patients with positive axillary Lymph nodes. Breast Cancer International Research Group TAX 316 protocol.

BCIRG 001/TAX 316: A multicenter phase III randomized trial comparing docetaxel in combination with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (TAC) versus 5-Fluorouracil in combination with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (FAC) as adjuvant treatment of operable breast cancer patients with positive axillary Lymph nodes. Breast Cancer International Research Group TAX 316 protocol.  Faculty members: “Ongoing trials of polychemotherapy for node—negative disease. En: Prognosis and treatment of node negative breast cancer. . Philadelphia, PA. USA, Ed.CE Gilmore, Phillips Group Oncology Comunications Co, 2001:p 18-19.

Faculty members: “Ongoing trials of polychemotherapy for node—negative disease. En: Prognosis and treatment of node negative breast cancer. . Philadelphia, PA. USA, Ed.CE Gilmore, Phillips Group Oncology Comunications Co, 2001:p 18-19.  Peters WP, Roaner G,Vredenburgh J et al. A prospective randomized camparison of two doses of combination alkylating agents as consolidation after CAF in high-risk primary breast cancer involving ten or more axillary lymph nodes: preliminary results of CALGB 9082/SWOG 9114/NCIC NA-13. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1999:18: 1ª. (abstr).