Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

The so-called and known "randomized controlled clinical trial", is the leading type of research design in the arsenal of biomedical research, particularly epidemiological research. The reason is simple: it stands as the only research design considered truly experimental and the experiment represents the fastest and most effective way of development of scientific knowledge.

In the language of clinical and epidemiological research, the clinical randomized controlled trial is the research design with less risk of bias. Bias is the nightmare of all epidemiological research and has been and remains the subject of articles, reflections and essays on methodology of epidemiological studies [1],[2],[3]. Unfortunately, clinical randomized controlled trials are used only in research that assesses therapeutic or preventive procedures because these are the only objects of research that have overcome the strong barrier of ethics in research involving human beings. For ethical reasons, the experiment is banned except when it comes to conduct a clinical trial to evaluate a therapeutic or preventive action after being approved by the competent authorities, i.e. the ethics committees for research [4].

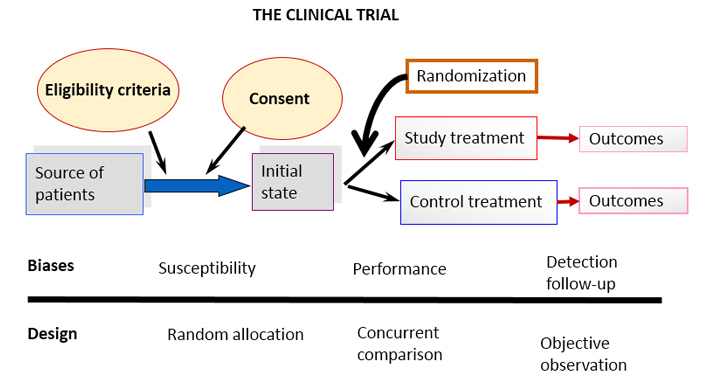

The purpose of the clinical trial design –as an experiment- is to isolate the study of all influence other than the objective of evaluating differences between treatments. The fundamental goal is to have equal groups in every way except for the therapeutic or preventive procedure assessed, so that whatever the outcome, can be attributed only to the procedure under consideration. On this basis we can formulate the so-called three golden rules of the design of a clinical trial which are aimed at confronting the most important biases in this type of research, since they directly threaten the chimerically desired similarity between groups [5].

Figure 1 provides a schematic of the design of a clinical trial, illustrating the most important biases and the three rules above mentioned.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of a basic clinical trial and potential sources of the most common biases.

All design elements, which have been introduced over time and shape modern clinical trials, are related to the effective implementation of these three golden rules. Consider, for example, intention to treat analysis [6] This rule forces researchers to include in the analysis of the results, paradoxically, those participants who were unable to complete the trial. The confusion generated in research-beginners (usually honest, so we think) is very high. The question is how to include in the results someone who withdrew or someone who had an accident and could not attend scheduled appointments. Well, the way to do it has already been conceived -that is what both the "last value carried forward, (LVCF)" and the “worst scenario” are for. The reason for doing it is related to possible "convenient" dissimilarities between groups, deliberately introduced by unscrupulous researchers prompted by the –yet more unscrupulous multinational pharmaceutical companies- as has already been reported in various scientific forums and in particular discussed in our journal [7].

More elaborate methodological elements of clinical trials in the narrow framework of an editorial in the Journal is impossible; methodological literature on clinical trials currently includes thousands or perhaps hundreds of thousands of articles, books, monographs and other scientific media.

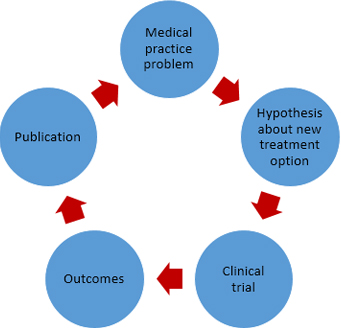

The cycle that links research with the application of its results in social practice inevitably passes by its publication (Figure 2).

Figura 2. Simplified schematic of relationship between medical practice, therapeutic research and publishing results.

Publication of the results of a clinical trial is a requirement of good clinical practice (the name given to the "international ethical and scientific quality standard for designing, conducting, recording and reporting trials that involve the participation of human subjects" [8]). It is also a requirement for research ethics and researchers (see Articles 35 and 36 of the Declaration of Helsinki, the latest version, October 2013) [9] and a former editorial in Medwave [10]. Furthermore, it is undoubtedly a rule of common sense. How not to publish the results of a study that has consumed considerable human and material resources? How to deprive the scientific community of a research result on this scale? How to deprive society of such a result? Even more, why contribute to unnecessary repetition of studies already carried out, leaving results unpublished?

Strangely enough, the fact is that the non-publication of research results (particularly from clinical trials) is a relatively common problem that worries today all of us who advocate a research practice born of ethics and honesty- and results in a bias not mentioned before that, this time, is not linked to research design itself [11]. A bias that leaves us helpless to fight for a medical practice that stems from scientific evidence and against which the weapons we have today are not enough. This is the so-called publication bias, i.e. the distorted idea that may be generated in the scientific community (and in the nonprofessional public); because some research results (in this case of clinical trials), are not published.

Unfortunately, there is proof that non-publication occurs not by chance and the tendency is not to publish results unfavorable to the hypotheses. The consequence of this bias is a false magnification of the goodness of therapeutic or preventive measures that can undoubtedly have a negative impact on society. Publication bias is today under study and discussion in scientific fields of various kinds [12],[13],[14].

Let us go on with the reporting of clinical trials. The first is to emphasize that the report should reflect in detail the trial design, in short, how the three aforementioned golden rules were met and all other issues added to them: eligibility criteria, treatment details, definition and operationalization of primary and secondary variables and even the way in which data is processed and analyzed.

An introduction is also necessary, i.e. substantiate the clinical trial (which must be from the initial project of course). Regardless of the barrier of going through an ethics committee, the investigator must bear in mind that experiment on humans is permissible only if it is supported by a strong scientific rationale.

Without overwhelming the reader, the results of clinical trials should be clear and transparent; a synthesis that allows the corresponding generalization is necessary; and confidence intervals for the effects are essential. Without them, readers will not have an accurate picture of the magnitude of the effect achieved, whether or not significant differences arise. Much has already been discussed about the ineffectiveness of p values and the difference between statistical significance and clinical significance [15],[16],[17].

Discussion of results is the weakest point but also necessary in the report of an investigation, particularly a clinical trial. The reader not only has the right to identify the results but to participate in the authors´ reflections about them and distinguish their place in in what is already known.

Having outlined the above, we come to what is probably of most interest to our readers / authors / researchers. How you can definitely make a good report of the results of a clinical trial that allows a decent publication? The answer could be complicated because writing in summary, without avoiding important questions on the foundation, the method and the results of a study that has spent time, resources, and in particular, knowledge and skills, is not a simple task.

Fortunately, in 1994 –as a consequence of the repeated allusions to reports of poor quality of clinical trials in medical journals and various disquisitions about this topic that worried publishers, medical scientists and health authorities- two articles proposing a structured way to report clinical trials were published. One of these was a special communication of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) [17] and the other a position paper of the Annals of Internal Medicine [18]. Both articles reported the ideas of two groups that worked independently in the search for a systematic and structured way to publish results of clinical trials: the Standards of Reporting Trials Group and the Working Group on Recommendations for Reporting of Clinical Trials in the Biomedical Literature.

In 1995, an editorial in JAMA [19] made a call for the union of these two groups in order to achieve a properly combined proposal. Both groups were receptive to this call and in 1996 came out the first version of a guide for reporting the results of clinical trials which was the product of the conjoined work of the first two groups [20]. It was first published in JAMA and the BMJ reported almost immediately adherence to the newly published guides and basically reproduced their statements [21].

The new guide took the title of CONSORT, which is the acronym of its name in English: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials. In 2001, the first major revision of the initial guidelines was published simultaneously in three prestigious medical journals: Annals of Internal Medicine [22], JAMA [23] and Lancet [24].

In 2010, a third revised CONSORT statement appeared. This time published by eight medical journals, some of them open access like PLoS Medicine [25], and BMC Medicine [26].

In addition to the initial guides and their two subsequent revisions directed to the basic design of a parallel trial, some extensions have been published for clinical trials with different specificities until today. We may distinguish CONSORT for non-inferiority studies [27]; CONSORT for cluster trials [28]; CONSORT for pragmatic trials [29]; and the one referred to studies of non-pharmacological treatments where trials for assessing surgical procedures, and rehabilitation therapies among others would be included [30].

The argument behind a good report of a clinical trial can be summarized in the words of Douglas G. Altman [21]:

Like all studies, randomised trials are open to bias if done badly. It is thus essential that randomised trials are done well and reported adequately. Readers should not have to infer what was probably done, they should be told explicitly. Proper methodology should be used and be seen to have been used.

The guide contains the basic CONSORT 2010 checklist with 25 items, some with sub-items, which actually gives 37 aspects that must be reported. The guide also suggests that the author include a patient flow diagram, which clearly displays the number of eligible participants, and the number that was lost in each subsequent stage; it contains a concrete proposal illustrated with a picture of how to do this flowchart. CONSORT is not limited to aspects of the method used to conduct the clinical trial but also includes elements of the introduction, the reporting of results and the discussion about them.

The author is thus committed not to forget the report of all aspects included in the guide or ultimately explain why some of the aspects, if any, was not completed. What we can call "good news" in this context is that researchers should identify and consider the CONSORT guide items not only when reporting their results, but also, since the planning of the trial.

As announced in the CONSORT website (http://www.consort-statement.org/about-consort/endorsers), over 600 biomedical journals and several publishers’ organizations such as the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME), support CONSORT today. A systematic review published in 2012 suggested that the use of CONSORT effectively improves the reporting of clinical trials [31].

Our Journal supports the CONSORT initiative and promotes its use by including the CONSORT guidelines among the documents that authors of clinical trials reports should review before submitting a manuscript to the journal evaluation. There is also a strong recommendation in the instructions to authors to "follow the standards recommended by the international initiative known as the Equator Network (Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research)" where CONSORT appears.

Clinical trials are the most efficient and effective way to evaluate the adequacy of a new therapeutic or preventive measure. Their use for this purpose contributes decisively to provide society of new treatments that ultimately really improve the quality of life of human beings. For this reason, it is not enough to conduct a clinical trial with the utmost rigor but its results should be published in the spaces aimed for this purpose and at the right time. CONSORT guidelines in its different variants are today the best pattern or model to produce an optimal report on the foundation, the methods and the results of a clinical trial.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with the subject of this article.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Autores:

Rosa Jiménez Paneque[1], Vivienne C. Bachelet[2]

Autores:

Rosa Jiménez Paneque[1], Vivienne C. Bachelet[2]

Citación: Jiménez Paneque R, Bachelet VC. Clinical trials and study reporting - CONSORT guidelines at the forefront. Medwave 2015 Sep;15(8):e6273 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2015.08.6273

Fecha de publicación: 30/9/2015

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2008:187-241. | CrossRef |

Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2008:187-241. | CrossRef | Rosenbaum L. Understanding bias--the case for careful study. N Engl J Med. 2015 May 14;372(20):1959-63. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Rosenbaum L. Understanding bias--the case for careful study. N Engl J Med. 2015 May 14;372(20):1959-63. | CrossRef | PubMed | Yordanov Y, Dechartres A, Porcher R, Boutron I, Altman DG, Ravaud P. Avoidable waste of research related to inadequate methods in clinical trials. BMJ. 2015 Mar 24;350:h809. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Yordanov Y, Dechartres A, Porcher R, Boutron I, Altman DG, Ravaud P. Avoidable waste of research related to inadequate methods in clinical trials. BMJ. 2015 Mar 24;350:h809. | CrossRef | PubMed | Standards and Operational Guidance for Ethics Review of Health-Related Research with Human Participants. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. | PubMed |

Standards and Operational Guidance for Ethics Review of Health-Related Research with Human Participants. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. | PubMed | Pocock SJ. Clinical Trials. Clinical Trials. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012: 2012. | Link |

Pocock SJ. Clinical Trials. Clinical Trials. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012: 2012. | Link | Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1999 Sep 11;319(7211):670-4. | PubMed |

Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1999 Sep 11;319(7211):670-4. | PubMed | Rada G. The requirement to disclose individual patient data in clinical studies will bring down the wall behind which the pharmaceutical industry hides the truth: the Kerkoporta is ajar. Medwave. 2013 Jun; 13(05):e5735. | Link |

Rada G. The requirement to disclose individual patient data in clinical studies will bring down the wall behind which the pharmaceutical industry hides the truth: the Kerkoporta is ajar. Medwave. 2013 Jun; 13(05):e5735. | Link | ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Guideline for good clinical practice E6(R1). ICH Harmon Tripart Guidel. 1996;1996(4):i – 53.

ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Guideline for good clinical practice E6(R1). ICH Harmon Tripart Guidel. 1996;1996(4):i – 53.  Assembly G. WMA Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 2013;(June 1964):1–8.

Assembly G. WMA Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 2013;(June 1964):1–8.  Bachelet VC, Rada G. Why the Helsinki Declaration now encourages trial registration, and publication and dissemination of the results of research. Medwave. 2013 Nov 15;13(10):e5846. | Link |

Bachelet VC, Rada G. Why the Helsinki Declaration now encourages trial registration, and publication and dissemination of the results of research. Medwave. 2013 Nov 15;13(10):e5846. | Link | Bachelet VC. Missing clinical trial data, but also missing publicly-funded health studies. Medwave. 2013. Jul;13(06):e5740. | CrossRef |

Bachelet VC. Missing clinical trial data, but also missing publicly-funded health studies. Medwave. 2013. Jul;13(06):e5740. | CrossRef | Ghersi D, Clarke M, Berlin J, Gülmezoglu A, Kush R, Lumbiganon P, et al. Reporting the findings of clinical trials: a discussion paper. Bull World Health Organ. 2008 Jun;86(6):492-3. | PubMed |

Ghersi D, Clarke M, Berlin J, Gülmezoglu A, Kush R, Lumbiganon P, et al. Reporting the findings of clinical trials: a discussion paper. Bull World Health Organ. 2008 Jun;86(6):492-3. | PubMed | Steinbrook R. Public registration of clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2004 Jul 22;351(4):315-7. | PubMed |

Steinbrook R. Public registration of clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2004 Jul 22;351(4):315-7. | PubMed | Gardner MJ, Altman DG. Confidence intervals rather than P values: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986 Mar 15;292(6522):746-50.

| PubMed |

Gardner MJ, Altman DG. Confidence intervals rather than P values: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986 Mar 15;292(6522):746-50.

| PubMed | Wolterbeek R. One and two sided tests of significance. Statistical hypothesis should be brought into line with clinical hypothesis. BMJ. 1994 Oct 1;309(6958):873-4. | PubMed |

Wolterbeek R. One and two sided tests of significance. Statistical hypothesis should be brought into line with clinical hypothesis. BMJ. 1994 Oct 1;309(6958):873-4. | PubMed | A proposal for structured reporting of randomized controlled trials. The Standards of Reporting Trials Group. JAMA. 1994 Dec 28;272(24):1926-31. Erratum in: JAMA 1995 Mar 8;273(10):776. | PubMed |

A proposal for structured reporting of randomized controlled trials. The Standards of Reporting Trials Group. JAMA. 1994 Dec 28;272(24):1926-31. Erratum in: JAMA 1995 Mar 8;273(10):776. | PubMed | Call for comments on a proposal to improve reporting of clinical trials in the biomedical literature. Working Group on Recommendations for Reporting of Clinical Trials in the Biomedical Literature. Ann Intern Med. 1994 Dec 1;121(11):894-5. | PubMed |

Call for comments on a proposal to improve reporting of clinical trials in the biomedical literature. Working Group on Recommendations for Reporting of Clinical Trials in the Biomedical Literature. Ann Intern Med. 1994 Dec 1;121(11):894-5. | PubMed | Rennie D. Reporting randomized controlled trials. An experiment and a call for responses from readers. JAMA. 1995 Apr 5;273(13):1054-5. | PubMed |

Rennie D. Reporting randomized controlled trials. An experiment and a call for responses from readers. JAMA. 1995 Apr 5;273(13):1054-5. | PubMed | Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996 Aug 28;276(8):637-9. | PubMed |

Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996 Aug 28;276(8):637-9. | PubMed | Altman DG. Better reporting of randomised controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 1996 Sep 7;313(7057):570-1. | PubMed |

Altman DG. Better reporting of randomised controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 1996 Sep 7;313(7057):570-1. | PubMed | Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG; CONSORT GROUP (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2001

Apr 17;134(8):657-62. | PubMed |

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG; CONSORT GROUP (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2001

Apr 17;134(8):657-62. | PubMed | Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001 Apr 18;285(15):1987-91. | PubMed |

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001 Apr 18;285(15):1987-91. | PubMed | Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001 Apr 14;357(9263):1191-4. | PubMed |

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001 Apr 14;357(9263):1191-4. | PubMed | Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2010 Mar 24;7(3):e1000251. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2010 Mar 24;7(3):e1000251. | CrossRef | PubMed | Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010 Mar 24;8:18. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010 Mar 24;8:18. | CrossRef | PubMed | Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Altman DG; CONSORT Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012 Dec 26;308(24):2594-604. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Altman DG; CONSORT Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012 Dec 26;308(24):2594-604. | CrossRef | PubMed | Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG; CONSORT Group. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012 Sep 4;345:e5661. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG; CONSORT Group. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012 Sep 4;345:e5661. | CrossRef | PubMed | Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008 Nov 11;337:a2390. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008 Nov 11;337:a2390. | CrossRef | PubMed | Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P; CONSORT Group. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Feb 19;148(4):295-309. | PubMed |

Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P; CONSORT Group. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Feb 19;148(4):295-309. | PubMed |