Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Palabras clave: gastric cancer, retrospective study, observational study, Argentina, treatment patterns, treatment costs

Aim

To assess patient and disease characteristics, treatment patterns and associated costs in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer in Argentina, in the public and private sectors.

Methods

A historic cohort of patients who had received first-line chemotherapy treatment (platinum analog and/or a fluoropyrimidine) and were followed-up for at least three months after the last administration of a first-line cytotoxic agent were eligible. Case-report forms were prepared based on medical records from four Argentinian hospitals. Estimates of treatment costs were also calculated using the unit costs of the participating hospitals.

Results

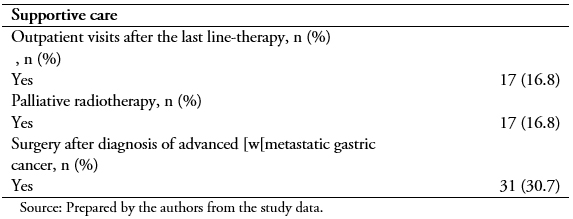

Of 101 patients, more than three quarters (79.2%) were male, 41.6% were diagnosed with metastatic stage IV disease (mean age, 57.7years), and 27.7 % had a smoking history. Before locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer diagnosis, 42.4% of the patients had received total gastrectomy. Ninety-seven percent of the patients received a doublet or triplet therapy, of which epirubicin in combination with oxaliplatin and capecitabine was the most common treatment (38%), followed by capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (29%). Around 36% of the patients responded to first-line treatment (complete and partial response). Out of the 76.2% of the patients who followed a second-line treatment, 37.7% were still administered a platinum analog and/or fluoropyrimidine. During the reported follow-up period, 50% of the patients progressed, and 32.8% had stable disease. The best supportive care consisted mostly of outpatient visits after last-line therapy (16.8%), palliative radiotherapy (16.8%), and surgery (30.7%). We observed significant differences between public and private hospital costs.

Conclusions

Understanding treatment patterns in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer may help address unmet medical needs for better patient management and improvement of their clinical outcome in Argentina.

Stomach or gastric cancer is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide, with an estimate of 951,000 new cases every year[1]. The incidence of gastric cancer has decreased in recent decades due to a reduction of dietary and environmental risk factors (e.g., availability of fresh fruit and vegetables, and decrease of salt intake, Helicobacter pylori infection and tobacco use, among others); however, it remains the third leading cause of cancer mortality[1],[2],[3]. In Argentina, gastric cancer was the fifth most common cause of cancer deaths in males and the seventh in females during 2011-2015, with rates of 7.4 and 3.1 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively[4]. Data from the Global Burden of Disease initiative show that mortality from gastric cancer in Argentina has increased slightly during the last 25 years; the largest number of deaths occur in older patients (≥ 65 years)[5]. Recent migrations from other Latin American countries may be associated with a further increase in the incidence[6].

Patients with gastric cancer have a favorable outcome when diagnosed at early stages (5-year survival rate: 85-100%); however, most patients with gastric cancer are only diagnosed at advanced stages of the disease, when survival rates decrease dramatically (5-20%)[2],[3],[7]. Gastric cancer management and treatment patterns for patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer differ considerably between countries, and there is no global consensus about the best therapeutic approach, particularly for second-and further-line treatments[7],[8],[9]. Peri- or post-operative chemotherapy improves survival and quality of life compared with best supportive care alone in patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer[8],[10],[11]. Doublet therapies consisting of a combination of platinum and fluoropyrimidines are the most commonly used first-line treatments; second-line treatment options include a variety of monotherapy and doublet combinations[12],[13],[14]. Palliative/best supportive care is common in patients with non-resectable or metastatic gastric cancer combinations[12],[13],[14], and best supportive care alone is administered when chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery are no longer helpful[3],[12],[13],[14].

In spite of being one of the main causes of cancer deaths in Argentina, and one whose impact has not decreased[4], there is very little information on the patterns of care and treatment of patients with gastric cancer. The most recent paper that we have been able to identify regarding the characteristics of patients with gastric cancer in Argentina is more than twenty years old[15]. Moreover, the degree of compliance with clinical guidelines and the cost of treatment is unknown[13],[14],[16]. Thus, the study aims to report patient and disease characteristics, first- and second-line treatment patterns and associated costs of patients with metastatic gastric cancer in Argentina, using information collected through a chart review approach from a sample of private and public hospitals in the country.

Study design

This observational, descriptive and prospective analysis of retrospectively collected data (historic cohort) was conducted in four tertiary centers in Argentina: three private health care institutions, namely Fundación Favaloro, Hospital Alemán Asociación Civil, and Instituto Alexander Fleming, and one public center, the Hospital de Gastroenterología Dr. Carlos Bonorino Udaondo. Data were collected from medical records. The patient inclusion criteria were: confirmed diagnosis of locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer (including gastroesophageal junction) between 1 January 2009 and 1 June 2016; completion of chemotherapy course as first-line treatment (i.e., completion of the cycles or finalization due to disease progression or toxicity), with platinum analogues (cisplatin, oxaliplatin, carboplatin) and/or a fluoropyrimidine (5-FU, capecitabine, S-1) with or without any other adjuvant medication, followed by either second-line treatment or best supportive care; age ≥ 18 at diagnosis; and availability of medical records including a follow-up of at least 3 months after the last administration of first-line treatment (except in case of death) to analyse the second-line treatment. Patients who were simultaneously participating or had participated in a controlled clinical study, and patients with other malignancies before or after metastatic gastric cancer diagnosis, were excluded from the study.

Data collection

Sociodemographic and clinical data and information regarding treatment and treatment patterns were collected from medical charts. Data collection included the retrospective review of patient medical records and data analysis. All participating hospitals selected researchers responsible for case report file filing. To warrant the validity and reliability of data, quality assurance of data collection was monitored in control visits. Data processing was performed to ensure data privacy and to safeguard sensitive information. Patient data were handled in compliance with national laws and regulations. This study was funded by Eli Lilly, and all participating institutions signed an agreement of collaboration with the promoter before the start of the study. All procedures were performed after presentation of the protocol and approval from the ethics committee and/or investigation committee of the participating hospitals (Ethics codes: Fundación Favaloro, n°601/16, acta number 549; Hospital Alemán Asociación Civil, 24/11/2015; Instituto Alexander Fleming, Res. 527; Hospital de Gastroenterología Dr. Carlos Bonorino Udaondo 30/11/2016).

Statistical analysis

The results of the descriptive statistical analysis for categorical variables are expressed as frequency and proportion; continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation or median where indicated. Estimation of overall costs and direct costs for first-line and second-line treatment was performed using 2017 unit costs from the Hospital de Gastroenterología ‘Dr. Carlos Bonorino Udaondo’ (public hospital) and Fundación Favaloro (private hospital) (see Annex I for unit costs). Treatment costs were computed taking into account the actual number of cycles received by each patient. In two cases of missing unit costs in one type of hospital (public/private), the figure was estimated from the information on the other type of hospital. The analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.4). At the time of cost calculation, one US$ was equivalent to 15.9 Argentinian pesos (January 31st, 2017). This conversion rate was used in the analyses.

Patients, disease and tumor characteristics

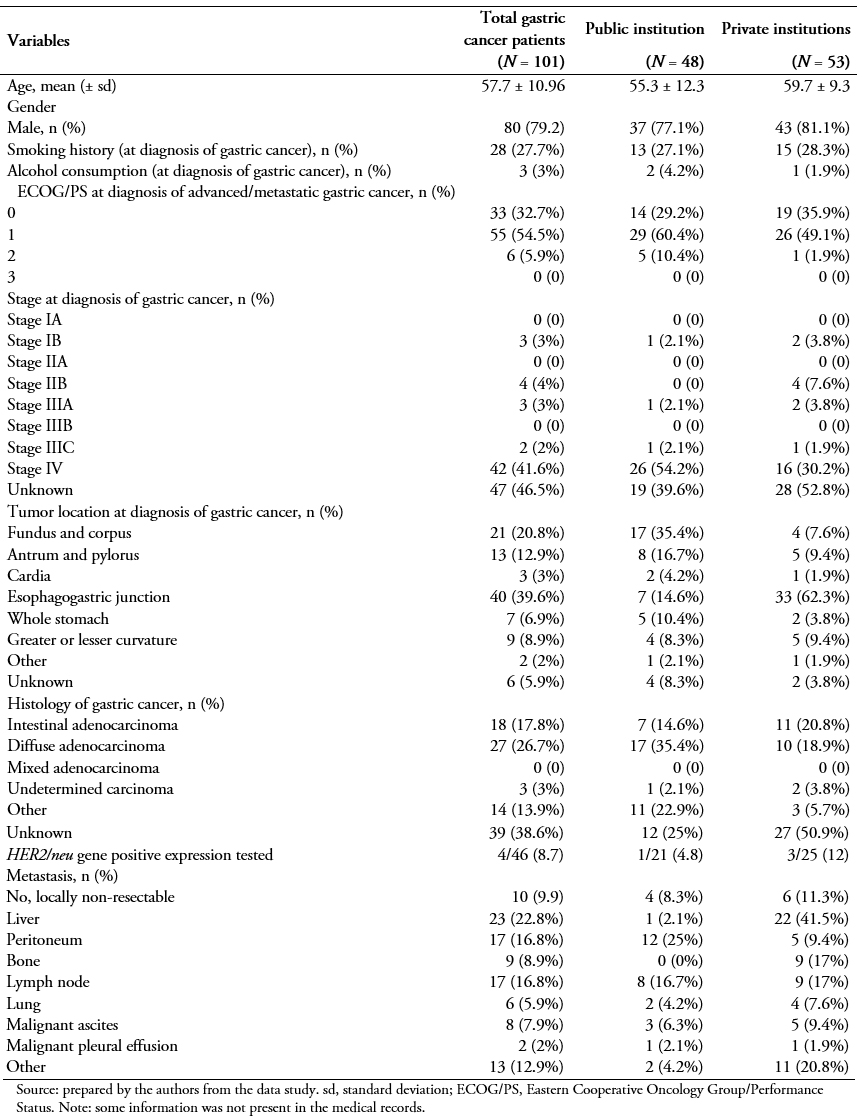

A total of 101 patients were included in this study after applying all inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). Forty-eight were recruited from the public hospital (Hospital Udaondo) and 53 from the private Hospitals (Fundación Favaloro, N = 42; Instituto Alexander Fleming N = 5; Hospital Alemán, N = 6). At diagnosis of metastatic gastric cancer, the mean patient age was 57.7 (standard deviation, 10.96) years and 79.2% of them were male. Of the overall study population, 27.7% had a smoking history, and a rather small proportion (3%) reported a history of alcohol abuse or dependence. At the index date (date of entry into the study), the majority of patients (54.5%) were symptomatic but completely ambulatory (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ECOG PS of 1), and yet approximately 6% of them were already unable to carry out any work activity (ECOG PS, 2; 5.9.%).

Upon initial diagnosis of gastric cancer, a large proportion of patients had already reached metastatic stage IV disease (41.6%) (Table 1). The second most frequently represented stage was stage III (5%). The most frequent primary tumor location was the gastroesophageal junction (39.6%), followed by the fundus and corpus (20.8%), and antrum and pylorus of the stomach (12.9%). According to the Lauren classification system, diffuse was the most frequently reported type (26.7%). Among the 46 patients tested for HER2 positivity, only 4 of them (8.7%) had positive status; 9.9% of the patients carried locally non-resectable tumours, and for those that had metastasized, the peritoneum (16.8%), nodes (16.8%), and liver (22.8.%) were the most commonly affected locations (Table 1).

Treatment patterns

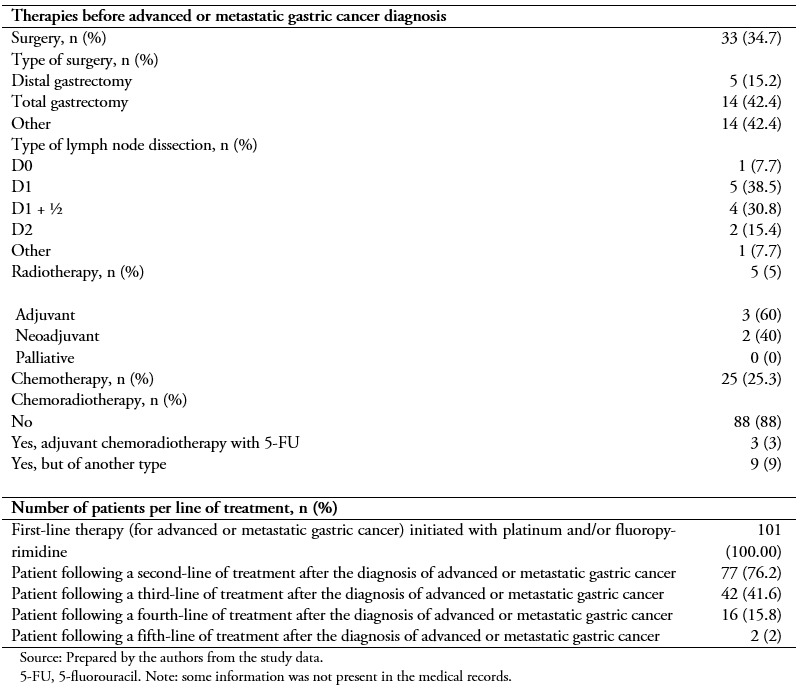

Patients had received different types of treatment before being diagnosed with locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer (Table 2). About one third (34.7%) of the study population had undergone surgery, and about one out of four (42.4%) had undergone total gastrectomy. Less commonly, patients had followed chemotherapy (25.3%), radiotherapy (5%), or adjuvant chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (3%) or another type (7.7%).

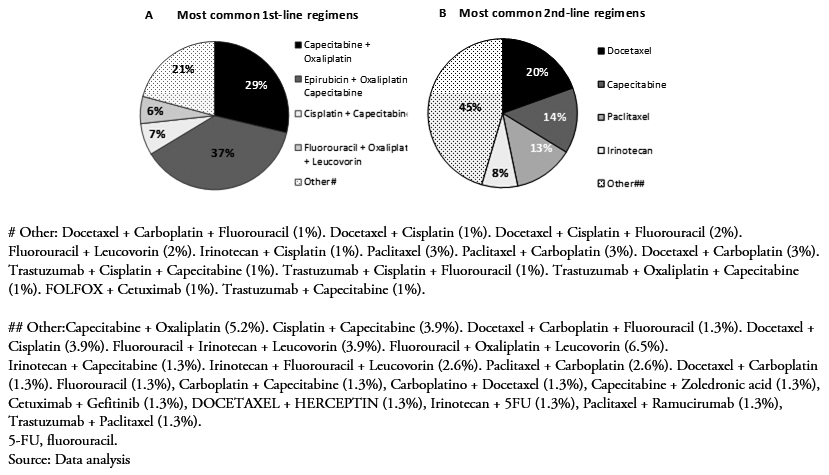

Upon diagnosis of advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, and following the inclusion criteria, all patients initiated first-line therapy with a platinum analog and/or a fluoropyrimidine. More than half of them (76.2%) followed a second-line of treatment, and fewer underwent a third- (41.6%) or fourth-line (15.8%) treatment (Table 2). Figure 1 presents all first- and second-line treatment combinations followed by the 101 and 77 patients, respectively.

Table 1. Patient and disease characteristics.

First-line treatment

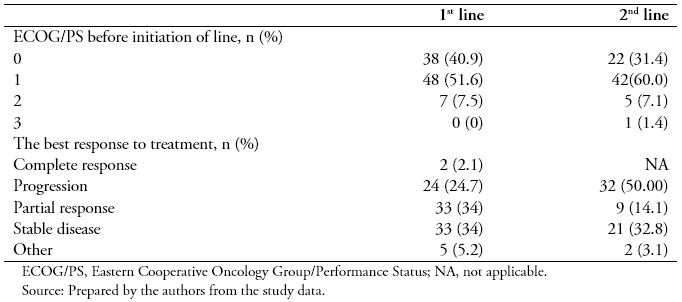

At the start of the therapy, more than half of the patients (51.6%) had an ECOG PS rating of 1, a few of them had a rating of 2 (7.5%), and 40.9% had a perfect performance status (ECOG PS, 0). There were no patients with an ECOG PS of 3 (Table 3).

Of the 101 patients enrolled in this retrospective study, 48 of them (47.5%) received a two-drug combination (doublet therapy), 50 of them (49.5%) a three-drug combination (triplet therapy), and only 3 of them (3%) a single drug treatment (monotherapy). Epirubicin + oxaliplatin + capecitabine was the most common treatment (38%), followed by capecitabine + oxaliplatin(29%), capecitabine + cisplatin (7%), and 5FU + oxaliplatin + leucovorin (6%) (Figure 1A). Other mono, double and triple therapies are shown in Figure 1A. Approximately 36% of the patients responded to treatment, either completely (2.1%) or partially (34%). The majority of them presented progressive (24.7%) and stable (34%) disease (Table 3).

Second-line treatment

In the second-line setting, a lower percentage of patients had an ECOG PS rating of 0, compared to first-line (Table 3). Second-line initiators mostly received monotherapy (56%) with docetaxel (19.5%), capecitabine(14.3%), paclitaxel (13%), or irinotecan (8%) (Figure 1B). Overall, treatment regimens based on a platinum analog and/or a fluoropyrimidine were still administered to 29 of them (37.7%). Targeted therapies (trastuzumab in combination with other agents only indicated for HER2 positive) accounted for as little as 3% of all second-line treatment patients (Figure 1B). There were no second-line chemotherapy total responders during the reported follow-up period, whereas 14% of them responded partially. Half of them (50%) progressed, and 32.8% of them stabilized (Table 3).

Supportive care and treatment-related costs

After the diagnosis of advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, best supportive care most frequently consisted of outpatient visits after the last line-therapy (16.8%) (Table 4).

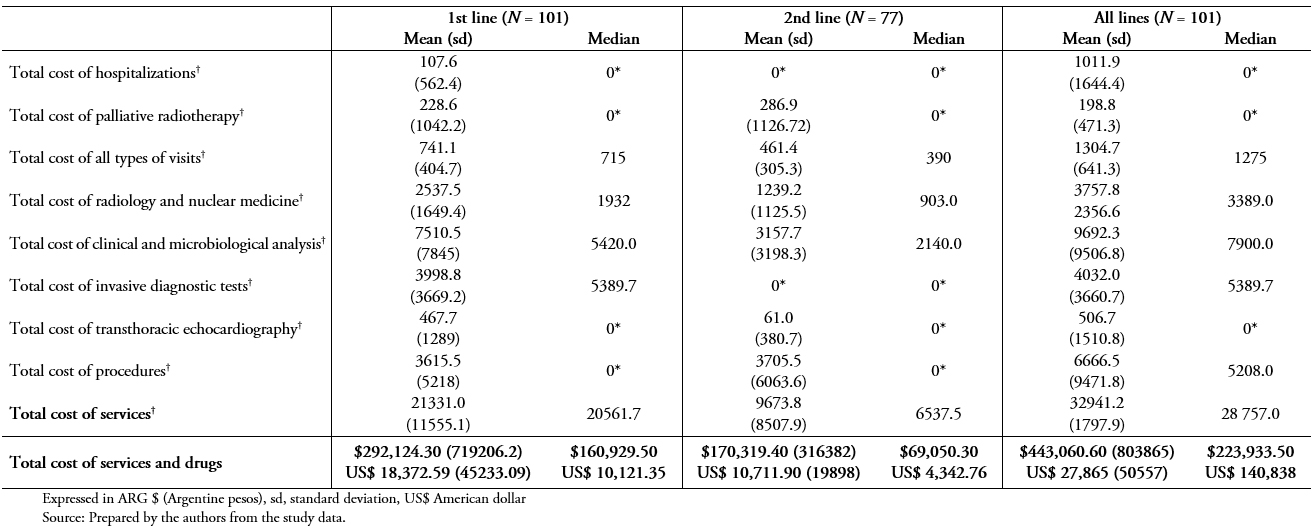

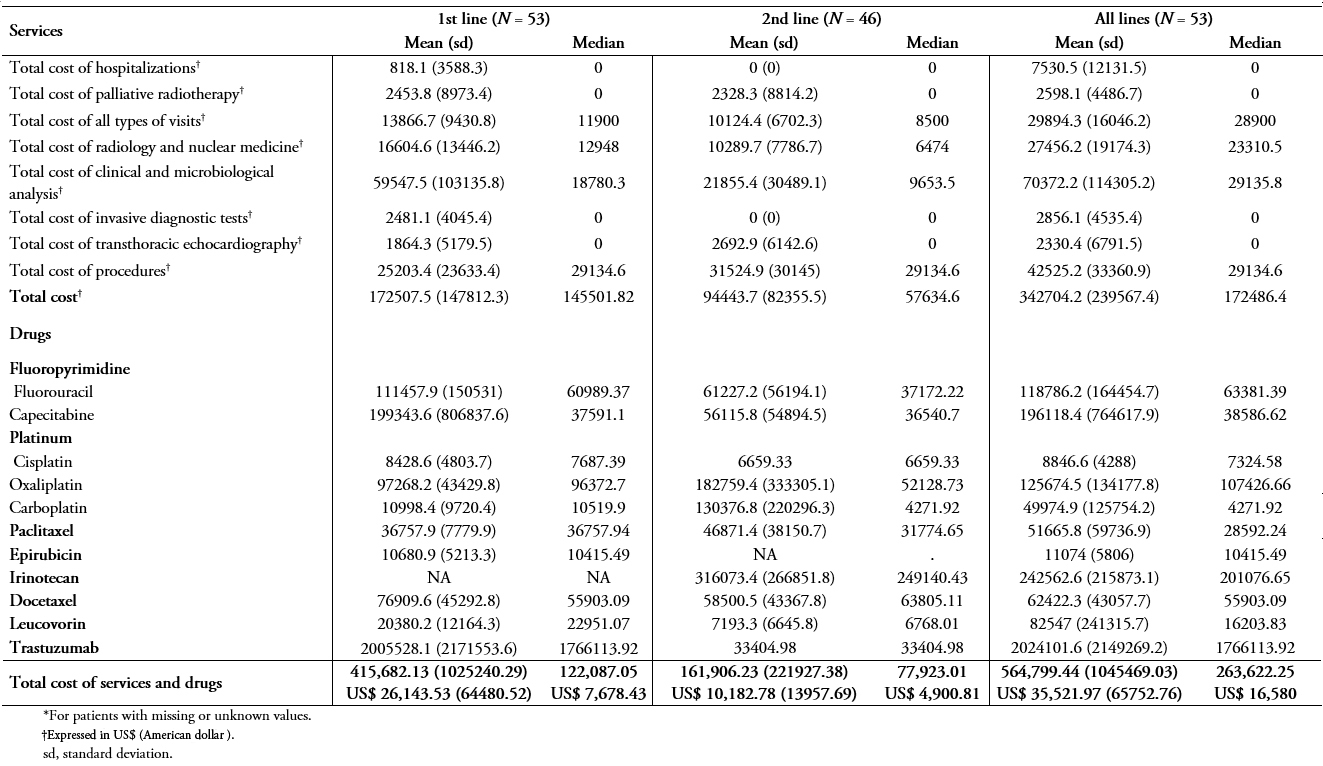

Table 5A shows the mean and median patient treatment costs in all patients using the public system unit costs. The total mean cost, including all services and specific treatments during the study period (from the 1st line to the last line therapy), was ARG $ 443,060.60 (standard deviation, 803865) (US$ 27,865.40; standard deviation, 50557.54).

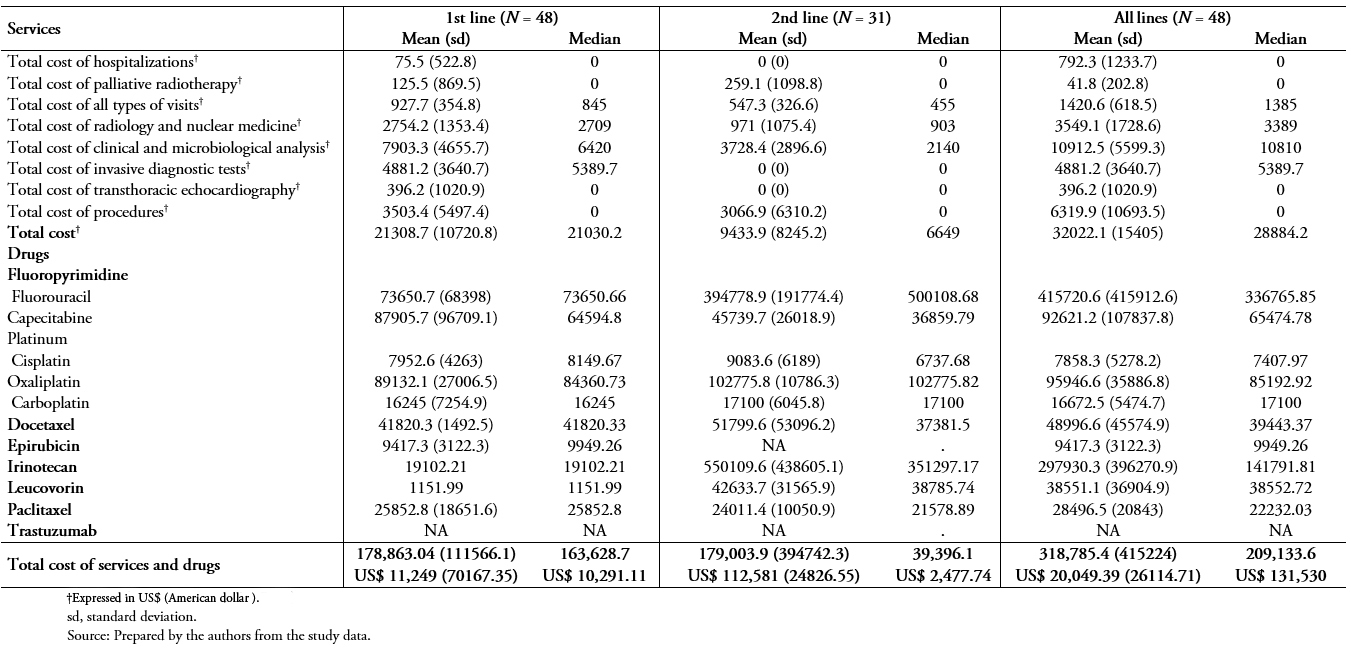

Table 5B shows the mean and median of patient treatment costs in patients being treated in public hospitals using the public system unit costs. The mean cost for all services (i.e., radiology and nuclear medicine; clinical and microbiological analyses; invasive diagnostic tests; transthoracic echocardiography; procedures; all types of visits; surgeries; hospitalizations; and palliative radiotherapy) and drug treatment per patient during the study period was ARG $ 318,785.40 (standard deviation, 415224) (US$ 20,049.39; standard deviation, 26114.72 ) of which ARG $ 10,912.5 (standard deviation, 5599.3) (US$ 6,863.20; standard deviation, 352.157) and ARG$ 6,319.90 (standard deviation, 10693.5) (US$ =3,974.77; standard deviation, 672.54) was invested in clinical and microbiological analysis and overall procedures, respectively.

Figure 1. Most common treatment regimens in first- (A) (N = 101) and second-line (N = 77) (B).

Table 4. Supportive care and other treatments received.

Table 5A. Treatment costs (using public unit costs), all patients (N = 101)

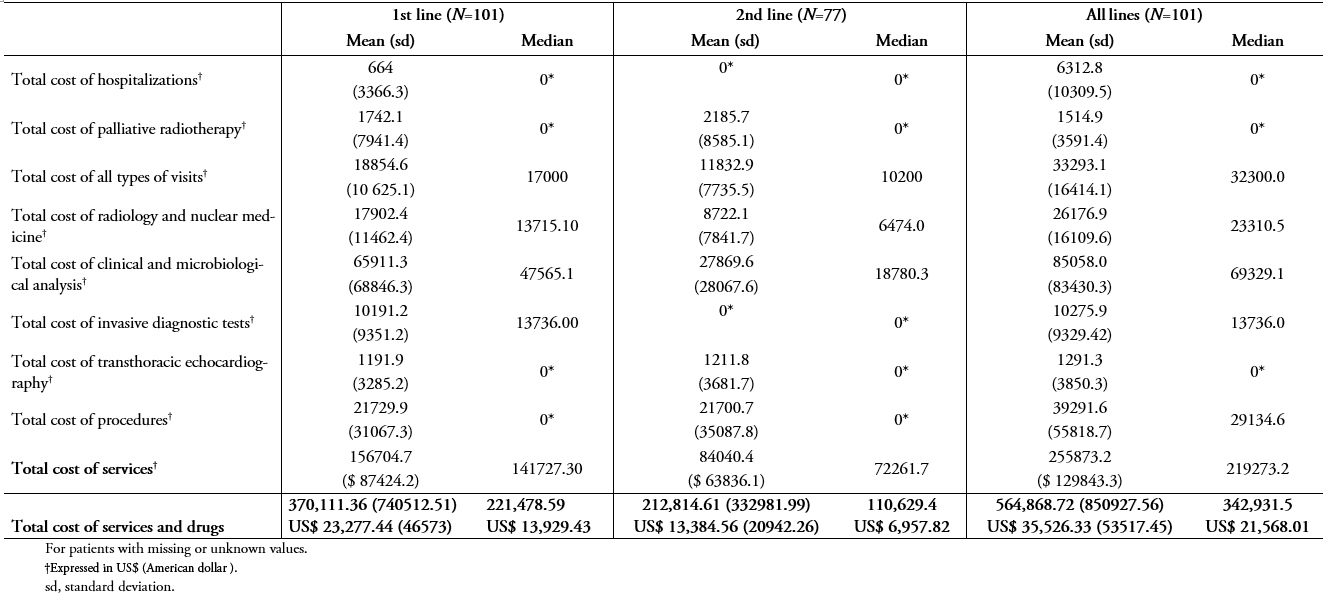

Table 6A and 6B show the same results as in Table 5A and B, but using private unit costs and patients being treated in private institutions. Considering all patients included in the study, the total costs of services and drug treatments in the 1st, 2nd, and all lines were greater in private than public institutions (n = 101, table 6A vs 5A). While the median costs of services and drug treatments during the study period in public institutions was ARG $ 223,933.50 (US$ 14,083.86), the median in private institutions was ARG $ 342,931.50 (US$ 21,568.01).

Table 6A. Treatment costs (using private unit costs) for all patients (N=101)

This study was designed to determine patient and disease characteristics, treatment patterns, supportive care, and treatment-related costs for locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer in Argentina. We found treatment patterns for patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer in Argentina to be highly heterogeneous, both in first- and second-line treatments. Triplet epirubicin + oxaliplatin + capecitabine (38%) and doublet capecitabine + oxaliplatin (29%) were the most frequent first-line treatments. Second-line treatments mainly included monotherapy (56%) with different agents: docetaxel (19.5%), capecitabine (14.3%), paclitaxel (13%), or irinotecan (8%). A significant proportion of patients (41.6%) continued with third-line treatment. Overall, the response rate to treatment was poor; during the follow-up period no second-line chemotherapy total responders were observed, and only 14.1% reported partial response.

Although gastric cancer is a global concern, clinical data available for patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer are still scarce, and national and international guidelines differ in their recommendations for the management of these patients[9],[12],[13],[14]. Recently, Bauer et al. compared the guidelines from Germany, UK, EU, USA, Canada, and Japan[9], and found significant discrepancies between recommendations, even when these were based on the same clinical studies[9].

Radical gastrectomy and perioperative therapy are indicated for stage IB–III gastric cancer[12],[13],[14], but guidelines differ on recommendations for accompanying chemotherapy. On the one hand, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical guidelines recommend pre- and postoperative chemotherapy with platinum plus fluoropyrimidine[13], while the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) indicates surgery followed by adjuvant chemoradiotherapy[12]. The Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment guidelines, on the other hand, recommend postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy[14]. Also, the extent of nodal dissection accompanying radical gastrectomy is likewise controversial[13]. In Western countries, only medically fit patients undergo D2 dissection (i.e., removal of perigastric lymph nodes plus those along the left gastric, common hepatic, and splenic arteries and coeliac axis), as trials have failed to prove any survival advantage with this procedure[13]. In contrast, several studies in Asia have shown that D2 resection is superior to D1 resection (removal of the perigastric lymph nodes)[14].

We observed great variability in the first-line treatments in our study, which included doublet and triplet regimens with platinum and fluoropyrimidines, and combinations with taxanes and/or anthracyclines. In our cohort, 47.5% of the patients received doublet therapy. Systemic treatment (chemotherapy) is more effective in terms of survival and quality of life than best supportive care alone for patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer[11],[17],[18],[19]. The gold standard in the first-line setting is platinum-based agents in combination with fluoropyrimidines[10],[12],[13]; 5-FU is the most frequently administered fluoropyrimidine[9]. However, oral capecitabine and S-1 are considered at least equivalent to intravenous 5-FU in terms of overall survival[8],[20],[21]. In our study, the most frequently administered doublet combination was capecitabine + oxaliplatin (29%), which was the second most frequent option for first-line treatment.

Around 50% of patients in our study received triplet therapy as first-line treatment. The use of triplets in first-line therapy is controversial[10],[13]; however, a meta-analysis has shown significant benefit from the addition of an anthracycline to a platinum/fluoropyrimidine doublet in first-line treatment[22]. Oxaliplatin is not inferior to cisplatin in combination with epirubicin and a fluoropyrimidine, and it is a good alternative to replace cisplatin in this setting[23],[24],[25]. Among triplets containing an anthracycline, the combination epirubicin + oxaliplatin + capecitabine was associated with longer overall survival than epirubicin + cisplatin + 5-FU[26]. In agreement with these studies, the most frequently administered triplet in our cohort was epirubicin + oxaliplatin + capecitabine (38%).

Only one patient received irinotecan as first-line treatment in our study population (doublet irinotecan + cisplatin). Irinotecan is recommended with 5-FU in first-line treatment[12], or in combination with leucovorin and 5-FU (FOLFIRI) as an alternative to platinum-based therapy[13]. Irinotecan + 5-FU is not superior to cisplatin + 5-FU, but it is better tolerated[27],[28], and in combination with leucovorin and 5-FU, it is an acceptable first-line regimen for advanced and metastatic gastric cancer patients[29].

The majority of taxane-containing first-line therapies in our study were doublets with either cisplatin or oxaliplatin. The use of taxanes in a first-line setting is recommended by several guidelines[12],[13],[14], as they significantly improve overall survival[30]. Nevertheless, adverse events associated with taxanes need to be considered when prescribing these therapies. For this reason, different variation regimes of docetaxel + epirubicin + 5-FU have been developed to reduce the associated severe adverse effects[10].

Finally, most patients with HER2 positivity were treated with trastuzumab in combination as first-line treatment, following the recommendations of several guidelines[12],[13]. Trastuzumab (which targets HER2) and ramucirumab (which targets VEGFR2) are the only targeted therapy drugs approved for gastric cancer treatment[31]. Ramucirumab is recommended as a preferred regimen for the treatment of gastric cancer after recurrence or progression, either in combination with paclitaxel or as monotherapy (at the same level as paclitaxel, docetaxel, and irinotecan) in the latest update of the NCCN guidelines[12]. In our study, doublet paclitaxel + ramucirumab was only used in one patient as second-line treatment.

About 76% of patients in our cohort initiated a second-line treatment, in line with values from European and Asian trials (up to 50% and 80% of gastric cancer patients)[10]. In patients with sufficient performance status, second-line treatment is recommended[12],[13],[14], as it improves overall survival and quality of life compared with best supportive care[32],[33],[34],[35]. Based on the development of recent medications, guidelines have included ramucirumab, single agent or in combination with paclitaxel, as an option for second-line therapy. Irinotecan, paclitaxel, and docetaxel are also included as options for second-line therapy if they have not been used before[10],[12],[13]. Our results are in line with these recommendations; 56% of patients in our cohort undergoing second-line treatment received monotherapy. Of these, 20%, 13%, and 8% received docetaxel, paclitaxel, and irinotecan, respectively. However, second-line therapies in our study also included combinations with platinum agents and fluoropyrimidines.

Response rates of patients in the study were poor and in line with the literature. Response to treatment in advanced gastric cancer or advanced or metastatic gastric cancer ranges between 28% and 54%[25],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40]. Although novel chemotherapy combinations show good response rates, complete response is not often observed[41],[42],[43]. After first-line treatment in our cohort, 2.1% of patients showed complete response and 34% partial response; after second-line treatment, only 14% of patients showed partial response, and half of the patients still presented disease progression. Finally, even though there is no clear evidence to supports the benefit of further treatment after second-line therapy[16], 41.6% of the patients in our study continued with a third-line treatment, while around 16% initiated fourth or fifth-line treatment.

Given the poor prognosis of gastric cancer, interventions that reduce the incidence of gastric cancer such as dietary modifications, stopping smoking, and eradication of H. pylori need to be considered as potentially valuable tools. A recent review[44] reported that the use of antibiotic treatment for the eradication of H. pylori could reduce the risk of gastric cancer in Latin America. Moreover, measures to detect diagnosis gastric cancer early may help limit the mortality of the disease. Gastric photo-fluoroscopy is the screening test for GC in Japan, as well as in some countries in Latin America, such as Venezuela[45].

Even though gastric cancer is an important health problem worldwide, information related to the economic burden of the disease is scarce. There have been, however, recent publications which sought to estimate the treatment patterns and costs of gastric cancer. Hess et al.[46], using electronic medical records and administrative data, estimated the chemotherapy treatment patterns, costs, and outcomes of patients with gastric cancer in the US. They observed similar patterns for first and second-line therapy.

In our study, we compared the treatment costs of public and private institutions. We observed significant differences between them, primarily in clinical and microbiological analyses.

The findings from this study need to be considered in the context of the following limitations. First, it is based on the retrospective collection of data from clinical charts. Some information may be missing if not properly recorded in those records. Second, survival analysis was not included in the study since information was not reliable, given that patients could change hospital during follow-up. Finally, to have a good representation of second-line treatments, we only included those patients with at least three months follow-up after the first-line treatment (except in case of death).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no recent studies describing the management of patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer in Argentina. Our results provide new information regarding disease characteristics, treatment types, and treatment patterns for advanced or metastatic gastric cancer patients in Argentina. Our data show high heterogeneity among treatments administered, both at first- and second-line settings, and overall poor patient response to treatment, particularly at second-line treatment. Future research should expand upon these data to better estimate treatment patterns, efficacies, and costs, and help inform individual and institutional therapeutic decisions on management of advanced and metastatic gastric cancer, so as to improve gastric cancer progression and quality of life in patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer.

Funding

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Co.

Author contributions

DN, LKPED, and SS contributed to the study design.

GM, MC, MR, JMO, JC, SS, DR collected the data.

MVM, JMH, and DN conducted the statistical analyses.

DN and SS wrote the first version of the manuscript. The remaining authors reviewed the manuscript for significant scientific content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

Lilly employees (DN, LKPED) were involved in the study design, and, as co-authors, of the preparation and revision of the manuscript. JMH has received honoraria for participating in Eli Lilly and Co., Roche and Lundbeck advisory boards.

Table 1. Patient and disease characteristics.

Table 1. Patient and disease characteristics.

Table 2. Therapies before locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer diagnosis and number of patients per line of treatment.

Table 2. Therapies before locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer diagnosis and number of patients per line of treatment.

Figure 1. Most common treatment regimens in first- (A) (N = 101) and second-line (N = 77) (B).

Figure 1. Most common treatment regimens in first- (A) (N = 101) and second-line (N = 77) (B).

Table 3. Patient characteristics before initiation of first- and second-line treatments and best response to treatment.

Table 3. Patient characteristics before initiation of first- and second-line treatments and best response to treatment.

Table 4. Supportive care and other treatments received.

Table 4. Supportive care and other treatments received.

Table 5A. Treatment costs (using public unit costs), all patients (N = 101)

Table 5A. Treatment costs (using public unit costs), all patients (N = 101)

Table 5B. Treatment costs (using public unit costs) for patients treated in public hospitals (N = 48).

Table 5B. Treatment costs (using public unit costs) for patients treated in public hospitals (N = 48).

Table 6A. Treatment costs (using private unit costs) for all patients (N=101)

Table 6A. Treatment costs (using private unit costs) for all patients (N=101)

Table 6B. Treatment costs (using private unit costs) for patients treated in private hospitals (N=53).

Table 6B. Treatment costs (using private unit costs) for patients treated in private hospitals (N=53).

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Aim

To assess patient and disease characteristics, treatment patterns and associated costs in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer in Argentina, in the public and private sectors.

Methods

A historic cohort of patients who had received first-line chemotherapy treatment (platinum analog and/or a fluoropyrimidine) and were followed-up for at least three months after the last administration of a first-line cytotoxic agent were eligible. Case-report forms were prepared based on medical records from four Argentinian hospitals. Estimates of treatment costs were also calculated using the unit costs of the participating hospitals.

Results

Of 101 patients, more than three quarters (79.2%) were male, 41.6% were diagnosed with metastatic stage IV disease (mean age, 57.7years), and 27.7 % had a smoking history. Before locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer diagnosis, 42.4% of the patients had received total gastrectomy. Ninety-seven percent of the patients received a doublet or triplet therapy, of which epirubicin in combination with oxaliplatin and capecitabine was the most common treatment (38%), followed by capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (29%). Around 36% of the patients responded to first-line treatment (complete and partial response). Out of the 76.2% of the patients who followed a second-line treatment, 37.7% were still administered a platinum analog and/or fluoropyrimidine. During the reported follow-up period, 50% of the patients progressed, and 32.8% had stable disease. The best supportive care consisted mostly of outpatient visits after last-line therapy (16.8%), palliative radiotherapy (16.8%), and surgery (30.7%). We observed significant differences between public and private hospital costs.

Conclusions

Understanding treatment patterns in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer may help address unmet medical needs for better patient management and improvement of their clinical outcome in Argentina.

Autores:

Diego Novick[1], Guillermo Mendez[2], Marcela Carballido[3], Mariela Rizzo[3], Juan Manuel O'Connor [4], Javier Castillo[5], Daniel Lee Kay Pen[6], Sara Siddi[7], Demian Rodante[8], Maria Victoria Moneta[7], Josep Maria Haro[7]

Autores:

Diego Novick[1], Guillermo Mendez[2], Marcela Carballido[3], Mariela Rizzo[3], Juan Manuel O'Connor [4], Javier Castillo[5], Daniel Lee Kay Pen[6], Sara Siddi[7], Demian Rodante[8], Maria Victoria Moneta[7], Josep Maria Haro[7]

Citación: Novick D, Mendez G, Carballido M, Rizzo M, O'Connor JM, Castillo J, et al. Retrospective analysis of patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer in Argentina. Medwave 2019;19(8):e7692 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2019.08.7692

Fecha de envío: 12/12/2018

Fecha de aceptación: 22/7/2019

Fecha de publicación: 24/9/2019

Origen: no solicitado

Tipo de revisión: Con revisión por pares externa con cuatro revisores, a doble ciego.

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015 Mar 1;136(5):E359-86. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015 Mar 1;136(5):E359-86. | CrossRef | PubMed | Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM. JAMA patient page. Stomach cancer. JAMA. 2010 May 5;303(17):1771. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM. JAMA patient page. Stomach cancer. JAMA. 2010 May 5;303(17):1771. | CrossRef | PubMed | Atlas de mortalidad por cáncer. Argentina 2011-2015 – Instituto Nacional del Cáncer [on line]. | Link |

Atlas de mortalidad por cáncer. Argentina 2011-2015 – Instituto Nacional del Cáncer [on line]. | Link | International Organization for Migration. Migration trends in South America, South American Migration Reports No. 1, 2017. The UN Migration Agency. [on line]. | Link |

International Organization for Migration. Migration trends in South America, South American Migration Reports No. 1, 2017. The UN Migration Agency. [on line]. | Link | Bang YJ, Yalcin S, Roth A, Hitier S, Ter-Ovanesov M, Wu CW, et al. Registry of gastric cancer treatment evaluation (REGATE): I baseline disease characteristics. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014 Mar;10(1):38-52. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bang YJ, Yalcin S, Roth A, Hitier S, Ter-Ovanesov M, Wu CW, et al. Registry of gastric cancer treatment evaluation (REGATE): I baseline disease characteristics. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014 Mar;10(1):38-52. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kim R, Tan A, Choi M, El-Rayes BF. Geographic differences in approach to advanced gastric cancer: Is there a standard approach? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013 Nov;88 2):416-26. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kim R, Tan A, Choi M, El-Rayes BF. Geographic differences in approach to advanced gastric cancer: Is there a standard approach? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013 Nov;88 2):416-26. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bauer K, Schroeder M, Porzsolt F, Henne-Bruns D. Comparison of international guidelines on the accompanying therapy for advanced gastric cancer: reasons for the differences. J Gastric Cancer. 2015 Mar;15(1):10-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bauer K, Schroeder M, Porzsolt F, Henne-Bruns D. Comparison of international guidelines on the accompanying therapy for advanced gastric cancer: reasons for the differences. J Gastric Cancer. 2015 Mar;15(1):10-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Digklia A, Wagner AD. Advanced gastric cancer: Current treatment landscape and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Feb 28;22(8):2403-14. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Digklia A, Wagner AD. Advanced gastric cancer: Current treatment landscape and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Feb 28;22(8):2403-14. | CrossRef | PubMed | Janowitz T, Thuss-Patience P, Marshall A, Kang JH, Connell C, Cook N, et al. Chemotherapy vs supportive care alone for relapsed gastric, gastroesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis of patient-level data. Br J Cancer. 2016 Feb 16;114(4):381-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Janowitz T, Thuss-Patience P, Marshall A, Kang JH, Connell C, Cook N, et al. Chemotherapy vs supportive care alone for relapsed gastric, gastroesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis of patient-level data. Br J Cancer. 2016 Feb 16;114(4):381-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Almhanna K, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Das P, et al. Gastric Cancer, Version 3.2016; Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. JNCCN Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 14(10), 1286-1312. | CrossRef |

Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Almhanna K, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Das P, et al. Gastric Cancer, Version 3.2016; Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. JNCCN Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 14(10), 1286-1312. | CrossRef | Smyth EC, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A, Arnold D, et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016 Sep;27(suppl 5):v38-v49. | PubMed |

Smyth EC, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A, Arnold D, et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016 Sep;27(suppl 5):v38-v49. | PubMed | Kodera Y, Sano T. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. | CrossRef | Link |

Kodera Y, Sano T. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. | CrossRef | Link | Speroni A, Fantana M, Boffi-Boggero H, García C, Foglia V. Epidemiología descriptiva del cáncer digestivo en 708 casos. Argentina 1992. Boletín la Acad Nac Med Buenos Aires. 1993;71: 517-29.

Speroni A, Fantana M, Boffi-Boggero H, García C, Foglia V. Epidemiología descriptiva del cáncer digestivo en 708 casos. Argentina 1992. Boletín la Acad Nac Med Buenos Aires. 1993;71: 517-29.  López-Moncayo H, Ospina-Nieto J, Rubiano-Vinueza J, Rey-Ferro M. Gastric Cancer. Surgical Management Guidelines 2009.Guia de manejo en Cirugia; 2009. | Link |

López-Moncayo H, Ospina-Nieto J, Rubiano-Vinueza J, Rey-Ferro M. Gastric Cancer. Surgical Management Guidelines 2009.Guia de manejo en Cirugia; 2009. | Link | Wagner AD, Grothe W, Haerting J, Kleber G, Grothey A, Fleig WE. Chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on aggregate data. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24: 2903-2909. | CrossRef |

Wagner AD, Grothe W, Haerting J, Kleber G, Grothey A, Fleig WE. Chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on aggregate data. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24: 2903-2909. | CrossRef | Glimelius B, Ekström K, Hoffman K, Graf W, Sjödén PO, Haglund U, et al. Randomized comparison between chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care in advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 1997 Feb;8(2):163-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Glimelius B, Ekström K, Hoffman K, Graf W, Sjödén PO, Haglund U, et al. Randomized comparison between chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care in advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 1997 Feb;8(2):163-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bouché O, Raoul JL, Bonnetain F, Giovannini M, Etienne PL, Lledo G, et al. Randomized multicenter phase II trial of a biweekly regimen of fluorouracil and leucovorin LV5FU2), LV5FU2 plus cisplatin, or LV5FU2 plus irinotecan in patients with previously untreated metastatic gastric cancer: a Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive Group Study--FFCD 9803. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Nov 1;22(21):4319-28. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bouché O, Raoul JL, Bonnetain F, Giovannini M, Etienne PL, Lledo G, et al. Randomized multicenter phase II trial of a biweekly regimen of fluorouracil and leucovorin LV5FU2), LV5FU2 plus cisplatin, or LV5FU2 plus irinotecan in patients with previously untreated metastatic gastric cancer: a Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive Group Study--FFCD 9803. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Nov 1;22(21):4319-28. | CrossRef | PubMed | Cassidy J, Saltz L, Twelves C, Van Cutsem E, Hoff P, Kang Y, et al. Efficacy of capecitabine versus 5-fluorouracil in colorectal and gastric cancers: a meta-analysis of individual data from 6171 patients. Ann Oncol. 2011 Dec;22(12):2604-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Cassidy J, Saltz L, Twelves C, Van Cutsem E, Hoff P, Kang Y, et al. Efficacy of capecitabine versus 5-fluorouracil in colorectal and gastric cancers: a meta-analysis of individual data from 6171 patients. Ann Oncol. 2011 Dec;22(12):2604-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Aguado C, García-Paredes B, Sotelo MJ, Sastre J, Díaz-Rubio E. Should capecitabine replace 5-fluorouracil in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer? World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 28;20(20):6092-101. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Aguado C, García-Paredes B, Sotelo MJ, Sastre J, Díaz-Rubio E. Should capecitabine replace 5-fluorouracil in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer? World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 28;20(20):6092-101. | CrossRef | PubMed | Okines AF, Norman AR, McCloud P, Kang YK, Cunningham D. Meta-analysis of the REAL-2 and ML17032 trials: evaluating capecitabine-based combination chemotherapy and infused 5-fluorouracil-based combination chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced oesophago-gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009 Sep;20(9):1529-34. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Okines AF, Norman AR, McCloud P, Kang YK, Cunningham D. Meta-analysis of the REAL-2 and ML17032 trials: evaluating capecitabine-based combination chemotherapy and infused 5-fluorouracil-based combination chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced oesophago-gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009 Sep;20(9):1529-34. | CrossRef | PubMed | Yamada Y, Higuchi K, Nishikawa K, Gotoh M, Fuse N, Sugimoto N, et al. Phase III study comparing oxaliplatin plus S-1 with cisplatin plus S-1 in chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015 Jan;26(1):141-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Yamada Y, Higuchi K, Nishikawa K, Gotoh M, Fuse N, Sugimoto N, et al. Phase III study comparing oxaliplatin plus S-1 with cisplatin plus S-1 in chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015 Jan;26(1):141-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Al-Batran SE, Hartmann JT, Probst S, Schmalenberg H, Hollerbach S, Hofheinz R, et al. Phase III trial in metastatic gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma with fluorouracil, leucovorin plus either oxaliplatin or cisplatin: a study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Mar 20;26(9):1435-42. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Al-Batran SE, Hartmann JT, Probst S, Schmalenberg H, Hollerbach S, Hofheinz R, et al. Phase III trial in metastatic gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma with fluorouracil, leucovorin plus either oxaliplatin or cisplatin: a study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Mar 20;26(9):1435-42. | CrossRef | PubMed | Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 3;358(1):36-46. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 3;358(1):36-46. | CrossRef | PubMed | Starling N, Rao S, Cunningham D, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, et al. Thromboembolism in patients with advanced gastroesophageal cancer treated with anthracycline, platinum, and fluoropyrimidine combination chemotherapy: a report from the UK National Cancer Research Institute Upper Gastrointestinal Clinical Studies Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Aug 10;27(23):3786-93. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Starling N, Rao S, Cunningham D, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, et al. Thromboembolism in patients with advanced gastroesophageal cancer treated with anthracycline, platinum, and fluoropyrimidine combination chemotherapy: a report from the UK National Cancer Research Institute Upper Gastrointestinal Clinical Studies Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Aug 10;27(23):3786-93. | CrossRef | PubMed | Dank M, Zaluski J, Barone C, Valvere V, Yalcin S, Peschel C, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid to cisplatin combined with 5-fluorouracil in chemotherapy naive patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction. Ann Oncol. 2008 Aug;19(8):1450-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Dank M, Zaluski J, Barone C, Valvere V, Yalcin S, Peschel C, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid to cisplatin combined with 5-fluorouracil in chemotherapy naive patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction. Ann Oncol. 2008 Aug;19(8):1450-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Moehler M, Kanzler S, Geissler M, Raedle J, Ebert MP, Daum S, et al. A randomized multicenter phase II study comparing capecitabine with irinotecan or cisplatin in metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction. Ann Oncol. 2010 Jan;21(1):71-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Moehler M, Kanzler S, Geissler M, Raedle J, Ebert MP, Daum S, et al. A randomized multicenter phase II study comparing capecitabine with irinotecan or cisplatin in metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction. Ann Oncol. 2010 Jan;21(1):71-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Guimbaud R, Louvet C, Ries P, Ychou M, Maillard E, André T, et al. Prospective, randomized, multicenter, phase III study of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine in advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: a French intergroup (Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive, Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer, and Groupe Coopérateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie) study. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Nov 1;32(31):3520-6. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Guimbaud R, Louvet C, Ries P, Ychou M, Maillard E, André T, et al. Prospective, randomized, multicenter, phase III study of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine in advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: a French intergroup (Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive, Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer, and Groupe Coopérateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie) study. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Nov 1;32(31):3520-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | Shi J, Gao P, Song Y, Chen X, Li Y, Zhang C, et al. Efficacy and safety of taxane-based systemic chemotherapy of advanced gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017 Jul 13;7(1):5319. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Shi J, Gao P, Song Y, Chen X, Li Y, Zhang C, et al. Efficacy and safety of taxane-based systemic chemotherapy of advanced gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017 Jul 13;7(1):5319. | CrossRef | PubMed | Apicella M, Corso S, Giordano S. Targeted therapies for gastric cancer: failures and hopes from clinical trials. Oncotarget. 2017 Jan 26;8(34):57654-57669. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Apicella M, Corso S, Giordano S. Targeted therapies for gastric cancer: failures and hopes from clinical trials. Oncotarget. 2017 Jan 26;8(34):57654-57669. | CrossRef | PubMed | Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D, Deist T, Hinke A, Breithaupt K, et al. Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer--a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Eur J Cancer. 2011 Oct;47(15):2306-14. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D, Deist T, Hinke A, Breithaupt K, et al. Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer--a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Eur J Cancer. 2011 Oct;47(15):2306-14. | CrossRef | PubMed | Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, Janowitz T, Coxon FY, Wadsley J, et al. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma(COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Jan;15(1):78-86. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, Janowitz T, Coxon FY, Wadsley J, et al. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma(COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Jan;15(1):78-86. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim DH, Park KW, Oh SY, Kwon HC, et al. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol. 2012 May 1;30(13):1513-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim DH, Park KW, Oh SY, Kwon HC, et al. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol. 2012 May 1;30(13):1513-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Roy AC, Park SR, Cunningham D, Kang YK, Chao Y, Chen LT, et al. A randomized phase II study of PEP02 (MM-398), irinotecan or docetaxel as a second-line therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2013 Jun;24(6):1567-73. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Roy AC, Park SR, Cunningham D, Kang YK, Chao Y, Chen LT, et al. A randomized phase II study of PEP02 (MM-398), irinotecan or docetaxel as a second-line therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2013 Jun;24(6):1567-73. | CrossRef | PubMed | Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008 Mar;9(3):215-21. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008 Mar;9(3):215-21. | CrossRef | PubMed | Ohtsu A, Shimada Y, Shirao K, Boku N, Hyodo I, Saito H, et al. Randomized phase III trial of fluorouracil alone versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus uracil and tegafur plus mitomycin in patients with unresectable, advanced gastric cancer: The Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG9205). J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jan 1;21(1):54-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ohtsu A, Shimada Y, Shirao K, Boku N, Hyodo I, Saito H, et al. Randomized phase III trial of fluorouracil alone versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus uracil and tegafur plus mitomycin in patients with unresectable, advanced gastric cancer: The Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG9205). J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jan 1;21(1):54-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, Shirao K, Doi T, Sawaki A, et al. Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Nov;10(11):1063-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, Shirao K, Doi T, Sawaki A, et al. Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Nov;10(11):1063-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Yamaguchi K, Shimamura T, Hyodo I, Koizumi W, Doi T, Narahara H, et al. Phase I/II study of docetaxel and S-1 in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006 Jun 19;94(12):1803-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Yamaguchi K, Shimamura T, Hyodo I, Koizumi W, Doi T, Narahara H, et al. Phase I/II study of docetaxel and S-1 in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006 Jun 19;94(12):1803-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Nov 1;24(31):4991-7. | PubMed |

Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Nov 1;24(31):4991-7. | PubMed | Wang Y, Yu YY, Li W, Feng Y, Hou J, Ji Y, et al. A phase II trial of Xeloda and oxaliplatin (XELOX) neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery for advanced gastric cancer patients with para-aortic lymph node metastasis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014 Jun;73(6):1155-61. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wang Y, Yu YY, Li W, Feng Y, Hou J, Ji Y, et al. A phase II trial of Xeloda and oxaliplatin (XELOX) neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery for advanced gastric cancer patients with para-aortic lymph node metastasis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014 Jun;73(6):1155-61. | CrossRef | PubMed | Okabe H, Ueda S, Obama K, Hosogi H, Sakai Y. Induction chemotherapy with S-1 plus cisplatin followed by surgery for treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009 Dec;16(12):3227-36. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Okabe H, Ueda S, Obama K, Hosogi H, Sakai Y. Induction chemotherapy with S-1 plus cisplatin followed by surgery for treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009 Dec;16(12):3227-36. | CrossRef | PubMed | Suzuki T, Tanabe K, Taomoto J, Yamamoto H, Tokumoto N, Yoshida K, et al. Preliminary trial of adjuvant surgery for advanced gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2010 Jul;1(4):743-747. Epub 2010 Jul 1. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Suzuki T, Tanabe K, Taomoto J, Yamamoto H, Tokumoto N, Yoshida K, et al. Preliminary trial of adjuvant surgery for advanced gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2010 Jul;1(4):743-747. Epub 2010 Jul 1. | CrossRef | PubMed | Corral JE, Mera R, Dye CW, Morgan DR.Helicobacter pylori recurrence after eradication in Latin America: Implications for gastric cancerprevention. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017 Apr 15;9(4):184-193. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Corral JE, Mera R, Dye CW, Morgan DR.Helicobacter pylori recurrence after eradication in Latin America: Implications for gastric cancerprevention. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017 Apr 15;9(4):184-193. | CrossRef | PubMed | Leja M, You W, Camargo MC, Saito H. Implementation of gastric cancer screening – the global experience. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014 Dec;28(6):1093-106. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Leja M, You W, Camargo MC, Saito H. Implementation of gastric cancer screening – the global experience. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014 Dec;28(6):1093-106. | CrossRef | PubMed | Hess LM, Michael D, Mytelka DS, Beyrer J, Liepa AM, Nicol S. Chemotherapy treatment patterns, costs, and outcomes of patients with gastric cancer in the United States: a retrospective analysis of electronic medical record (EMR) and administrative claims data. Gastric Cancer. 2016 Apr;19(2):607-615. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hess LM, Michael D, Mytelka DS, Beyrer J, Liepa AM, Nicol S. Chemotherapy treatment patterns, costs, and outcomes of patients with gastric cancer in the United States: a retrospective analysis of electronic medical record (EMR) and administrative claims data. Gastric Cancer. 2016 Apr;19(2):607-615. | CrossRef | PubMed |