Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Palabras clave: adhesive capsulitis, manual therapy, physical therapy modalities, randomized controlled trial, glenohumeral joint

OBJECTIVE

To compare the short-term efficacy of a glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique versus conventional physiotherapy for the improvement of the range of external rotation in patients with primary adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder.

METHODS

This is a randomized clinical trial conducted at Hospital Clinico San Borja Arriaran in Chile. Fifty-seven patients with an age range of 50 to 58 years old were enrolled in two groups. Both groups were randomized to receive a treatment of 10 sessions: the experimental group (n=29) received a glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique after training with a cycle ergometer, and the control group (n=28) received conventional physiotherapy. The primary outcome measure was range of passive movement in external rotation; secondary outcomes were forward flexion and shoulder abduction, pain perception using the visual analogue scale and functionality test using the Constant-Murley Score.

RESULTS

The study had the statistical power to detect a difference of four degrees between the groups in the improvement of the range of external rotation at the end of the treatment period. The experimental group showed a significant improvement with a mean difference of 46.3 degrees (SD=8.7) compared to 18.1 (SD=7.2) in the control group (p<0.0001). There was also a decrease in the perception of pain (p= 0.0002) and improved function (p< 0.0001) in the group treated with glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique.

CONCLUSIONS

The glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique applied after training with cycle ergometer is an effective short-term technique to treat primary adhesive capsulitis decreasing the severity of pain and improving joint function compared with conventional physiotherapy treatment. The degree of increase in shoulder external rotation is more than 20 degrees beyond the increase achieved with conventional treatment.

Adhesive capsulitis is a common musculoskeletal condition characterized by shoulder pain of spontaneous onset, associated with progressive loss of scapulohumeral motion and its etiology is unknown. Many terms have been used to define this clinical condition. It was first described by Duplay in 1896 who called it “scapulohumeral periarthritis” [1]. Later in 1934, Codman coined the concept of “frozen shoulder” [2]. Nevertheless, current literature views this concept as very broad and it could cause confusion since it involves different pathologies which present as pain and shoulder stiffness; such as calcific tendonitis, bicipital tenosynovitis, glenohumeral and acromioclavicular arthritis and break of the rotator cuff [3],[4],[5],[6],[7]. Neviaser, during the pre- arthroscopic era, was the first one to use the concept of “adhesive capsulitis” [8], to describe findings of chronic inflammation and fibrosis of the joint capsule, although arthroscopic examination would support the term fibrotic capsulitis with absence of intra-articular adhesions [9],[10].

In 1944 American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) defined it as “a condition characterized by functional restriction of both active and passive shoulder motion for which radiographs of the glenohumeral joint are essentially unremarkable except for the possible presence of osteopenia or calcific tendonitis” [11]. Zuckerman suggested a type of classification where primary or idiopathic adhesive capsulitis was not associated with some systemic condition or trauma; there was no previous event to attribute to this condition, so its etiology is unknown [11],[12].

It is considered as a self – limiting disease. Reeves et al. [13] based on adhesive capsulitis natural history distinguished three sequential stages (painful, stiffness and recovery stage). Later Hannafin and Chiaia [14] described four stages, including the arthroscopic stages described by Neviaser [4], clinical examination and histological findings. Stage 1, Pre-Adhesive Stage: duration of symptoms 0-3 months; pain with active and passive range of movement with gradual limitation in the middle range and all final shoulder movements. From an histological point of view, there is only diffuse glenohumeral synovitis. Stage 2 or Freezing Stage: duration three to nine months; patients frequently have a high level of pain near end-range of movement with significant limitations related to shoulder mobility. Histologically, there are hypertrophic and hypervascular synovitis, fibroplasia and scar formation in the underlying capsule. Stage 3 or Frozen Stage: duration 9 to 15 months; there is minimum pain, but only in extreme ranges; limitation in all shoulder movements is important. Histologically there is not synovitis nor hypervascularity, but there is more fibrosis and joint capsule density is increased. Finally Stage 4 or Thawing Stage: duration 15 to 24 months; patients present gradual and spontaneous recovery and shoulder mobility and function.

Despite the acceptance of this classification in literature, its usefulness from the clinical point of view is controversial, because pain and range of motion limitation are present in all adhesive capsulitis stages. Besides, in many cases the previously described chronological sequence has not been observed, since there are patients who have suffered from pain and range of motion limitation for more than two years; even 10% of them never reach total range of motion of the affected shoulder [15],[16],[17].

Kelley et al. [18] have proposed a classification system based on patient´s irritability level. It could be a very useful guideline in order to make decisions about therapeutic procedures for adhesive capsulitis treatment. Under low irritability, according to the visual analogue scale, patients show pain < 3/10, neither nocturnal pain nor at rest, and the final pain sensation is tolerable; active movement limitation is similar to passive movement and both present low levels of disability. These patients generally inform having stiffness rather than pain as the main complaint. High irritability patients show pain >7/10 in a visual analogue scale, mainly with passive movement, nocturnal pain and at rest; they report high levels of disability. These patients generally inform pain rather than stiffness as the main complaint.

In spite of the fact that there is no specific diagnostic criterion, patients with primary adhesive capsulitis show coherent history in the clinical exam [4],[8],[13]. Regarding clinical presentation, there are specific factors that are useful to determine patient´s level of irritability [18]. First, the capacity to sleep through the night means less irritability and it is indicating that synovitis / angiogenesis begin to resolve and they are at stage 3. The second factor has to do with pain or stiffness as a predominant symptom; in this case, the patient experiences more stiffness than pain and he probably has less symptomatic synovitis /angiogenesis and more fibrosis. The third factor has to do with symptoms having improved or got worse over the last three weeks; improving symptoms might indicate that the patient has advanced from stage 2 to stage 3 and irritability level has decreased. This is very important because the effects of therapeutic agents, especially physiotherapy techniques and physical agents employed to treat this medical condition, are closely related to the ability of the affected tissue to withstand stress or mechanical load, concept often described as "tissue irritability " [19].

According to current knowledge of natural history of the disease, the traditional concept of benign nature and self-limited course is controversial [5],[13],[20],[21],[22], because there is a percentage of patients whose symptoms, mainly range of motion, will not solve spontaneously, being external rotation the most restricted physiological movement [20],[23],[24]. To treat this impairment some physiotherapy techniques are prescribed. The use of some physical agents in combination with an exercise program has shown benefits in the improvement of movement range at all levels [20],[21],[25],[26], except for shoulder rotations [27]. Some studies have shown that manual therapy decreases the deficit of glenohumeral rotational movement, characteristic of this condition, especially the external rotation [24],[28],[29],[30]. In the literature, one of the most widely studied technique for this purpose is the glenohumeral posterior mobilization (GPM) [31],[32],[33],[34]. It is a high-degree joint mobilization technique, where a humeral axial distraction type III (according to Kaltenborn) is carried out and a kept glide or slide in posterior direction of the humeral head towards the end of glenohumeral range of motion available. Its foundations are based on the elongation of the posterior capsule through the application of stress, reaching the plastic phase of such structure by changing its shortening through permanent deformation [35], allowing the movement of the humeral head on the glenoid cavity [31],[32],[33],[34].

In this study, we compared therapeutic effectiveness of two treatment modalities in patients with shoulder primary adhesive capsulitis diagnosis: one of them is a glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique after training with a cycle ergometer, and the other one is a conventional physiotherapy program based on ultrasound application, active and self-assisted ROM exercises and isometric exercises.

This is a randomized clinical trial conducted in the Physical Therapy Department of Hospital Clinico San Borja Arriaran in Chile, under the approval of the Central Metropolitan Health Service Ethics Committee. From 2009 to 2013 fifty-seven patients with primary adhesive capsulitis were enrolled. An orthopedic surgeon based on medical records, clinical symptoms and imaging studies, made the diagnosis. All patients received non-steroids anti- inflammatory drugs, oral analgesics and physiotherapy. At the beginning of the therapy, the average time of the emergence of their illness was five months. All subjects signed a consent form approved by the institutional ethical committee and before their first assessment; patients were randomly assigned to each protocol treatment.

Passive range of motion was measured for external rotation, forward flexion and glenohumeral abduction. Pain perception was assessed through a visual analogue scale and the functionality degree was determined by Constant-Murley Score (CMS). Evaluations were done during the first and the tenth sessions.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Sample size- hypothesis

The sample size calculation was performed using the Epidat 4.1 program. The necessary initial data was based on a randomized clinical study conducted by Carette et al. [26]. They used a conventional physiotherapy treatment similar to our study, in which, at the end of the tenth session, they reported a mean improvement of 9.6 degrees with a standard deviation of 3.2 degrees for the range of passive external rotation movement. Therefore, this 3.2 was considered as the initial value of the common standard deviation and that variable was selected to calculate our sample size. It was found that for α= 0.05 (probability of committing Type I error) and a statistical power of 80% to detect a minimum difference of 4 degrees of improvement between treatments, a minimum of 25 patients per group was needed. According to this result, authors have stated as a working hypothesis, that there is at least a difference of 4 degrees between increases in passive range of motion of external rotation for the group treated with the glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique after training with a cycle ergometer compared with the conventional physiotherapy treatment program.

Randomization and blinding

Participants were assigned to groups by a sequence of random numbers generated by a computer program before the beginning of patients selection. The number assigned to each group remained in a sealed envelope with the number visible on the outside. Each selected patient was assigned a number by order of arrival. Thus, the envelope corresponding to each patient (by number) would be opened as near the beginning of treatment as possible. The purpose of this was to conceal the allocation to the researcher who was deciding the entry of the study subjects.

Given the nature of the therapeutic interventions studied, the physiotherapist could not be in blind condition. However, the evaluator was external to the research group, and when measuring the study variables in the first and tenth sessions, he did not know to which group each patient belonged.

Interventions

Experimental group was treated for 15 minutes with upper extremity cycle ergometer and then the glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique was performed, with the patient in the supine position, in 30º to 40º of abduction and a light external rotation of the shoulder depending on tolerance. First, an axial distraction type III was made according to Kaltenborn, followed by posterior glide during one minute without oscillations. This maneuver was repeated 15 times with one minute rest for each. Control group received a conventional physiotherapy treatment program consisting of ultrasound (1MHz, 1.5 W/cm2 continuously for 10 minutes within 4 cm2), self-assisted exercises, Codman exercises, Swiss ball exercises and isometric exercises depending on tolerance [26]. Both groups performed 10 sessions, twice or three times a week.

Operational definitions of variables

In both groups, a physiotherapist external to the research group conducted the evaluations. The professional has a post degree in orthopedic manual therapy (Master) and more than five years of experience in the clinical area.

Primary outcomes

Both groups were evaluated with goniometer, passive range of motion was measured for external rotation, forward flexion and glenohumeral abduction. A Bioperson ® goniometer of 360º, 18-cm arms and an extension of 54 cm was used. Participants were evaluated in the supine position with as little clothing as possible in order to not alter or obstruct the upper extremity valuation. This measurement has shown to be a reproducible method for evaluating the passive range of motion in patients with adhesive capsulitis [36].

Secondary outcome measures

To assess pain a visual analogue scale (VAS) was used. This consists of an horizontal line of 10 cms length, where the left end represents cero or without pain and the right end represents 10 or the worst imaginable pain. The pain visual analogue scale measurement is self-completed by the subject. The respondent is asked to place a line perpendicular to the visual analogue scale line at the point that represents his/her pain intensity. It is a simple and reproducible valuation method [37], which has proved to be valid in chronic pain conditions [38].

Functional valuation was measured through the Constant-Murley score. The first two values are subjective valuations based on the patient’s interview. A maximum of 15 points were assigned to pain and 20 points were assigned to function (daily routine activity). The other two assessed values are more objective; active range of motion has got a maximum score of 40 points and muscle strength 25 points, adding a maximum punctuation of 100 [39]. This functional rating scale has a high correlation with other scales and shoulder specific questionnaires [Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index (WORC), Penn Shoulder Score, Simple Shoulder Test, Questionnaire Shoulder Oxford, Oxford Shoulder Instability Questionnaire (OSIQ) or Subjective Shoulder Rating System]. It also shows high reliability and sensitivity [40].

Statistical analysis

Data on quantitative variables are presented as average and standard deviation. To compare the initial baseline data regarding the variables gender and dominant side affection, a Chi-square test was used. For each quantitative variable, normality was first assessed with a Shapiro test. The comparison between groups for these variables is then performed using Student's t test or Wilcoxon test (Mann-Whitney) for two independent samples according to the results of normality assessment. In both cases, the level of significance was set at 0.05. Considering the size of the sample, the confidence intervals of 95% for the mean differences between groups were calculated by the conventional method for all quantitative variables. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata IC program11, Epidat 3.1 and 4.1.

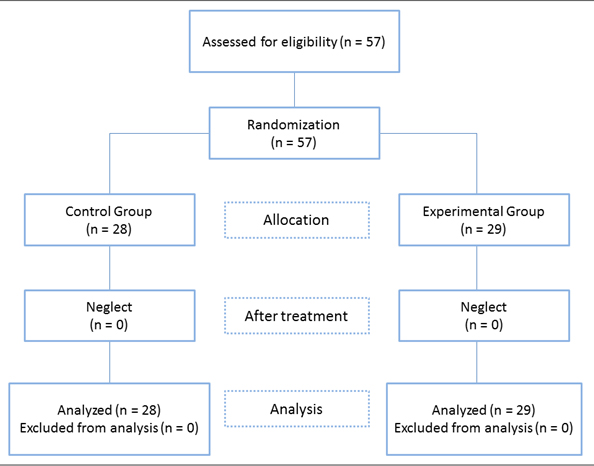

Prior to the study, the authors considered an analysis of intention to treat so that if there is loss of information, these patients would not be excluded from the final statistical calculation and the analysis of results (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of patients through the phases of the trial.

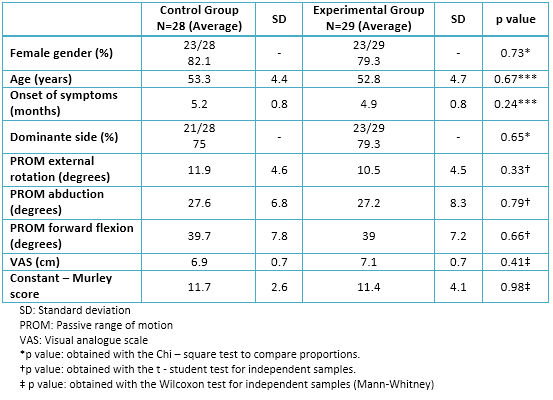

In this study, the statistical analysis was performed only per protocol. It was not necessary to make an intention to treat analysis, since there were no losses. Based on it, outcomes were obtained from all the patients included in the trial. The initial baseline results of each group are presented in Table 1.The normality hypothesis was not rejected for the variables: external rotation passive range of motion (p= 0.52), forward flexion (p=0.30) and abduction (p=0.68); accordingly, t-test was used for comparison between groups regarding these variables. Neither of the variables evaluated at baseline showed statistically significant inter groups differences (all p-values were above 0.2).

Table 1. Baseline of patients with primary adhesive capsulitis in both groups treatment.

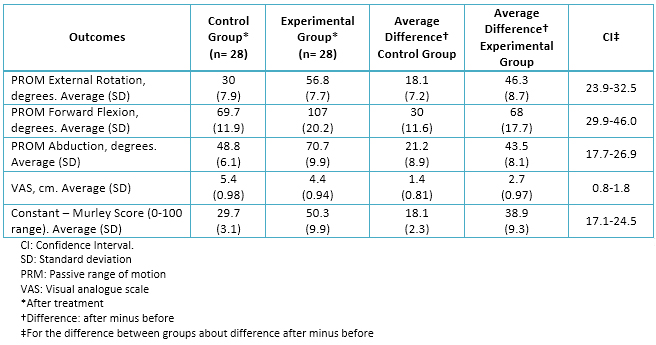

At the end of the treatment protocols, both groups showed improvements in all of the evaluated parameters. Table 2 shows the average values of the variables evaluated at the end and the differences between the final and the initial value. For all the variables, the hypothesis of equality of means in the population was rejected and the experimental group was favored, this is reflected in the confidence intervals for the differences between groups.

Table 2. Summary results for variables measuring response to treatment.

For the analysis of visual analogue scale and Constant-Murley score, the test results were Shapiro p=0.03 and p=0.045 respectively. According to this, the Wilcoxon test was used to compare both groups. For both variables a difference statistically significant was found in favor of the experimental group: visual analogue scale shows a decrease of 2.7 cm compared with

In this study, two groups of patients with primary adhesive capsulitis were treated with two different modalities. One group was treated with a high-degree of joint mobilization technique, applied in posterior way in the end range of available motion in conjunction with cycle ergometer training. The other group was treated with a conventional physiotherapy treatment program.

Data for both groups at baseline were statistically similar. The 82.1 to 79.3% of the sample were women, and the average startup time of treatment was five months from the onset of symptoms. Regarding dominance, from 75 to 79.3% of patients had the dominant side affected. In relation to measurements of passive movement range of external rotation, forward flexion, abduction and Constant-Murley score were similar in both groups. At the visual analogue scale, the experimental group had an average slightly higher than the control group, although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.41). Regarding the development of treatment, all patients completed their respective therapeutic programs, no dropouts occurred, and there were no reports on any problems about the tolerance of the technique and / or the doses applied. At this point, it is essential to exclude patients with high irritability. The frequency of the sessions was two to three times per week, with total treatment duration of five to six weeks.

Although this study is not aimed at performing a cost analysis, the experimental group sessions had an average duration of 35 minutes, compared to two hours 45 minutes of the control group. We believe that the cost-effectiveness aspect should be considered in subsequent studies.

When reviewing the literature on the effects of different manual therapy techniques in improving the range of movement in patients with primary adhesive capsulitis; the systematic review of Ho et al. [41] and Favejee et al. [42] reported moderate evidence for short and long-term in favor of the techniques of high-degree of mobilization applied at the final range of motion available. Meanwhile, from the systematic review of Jain et al. [43] these techniques are strongly recommended for the improvement of the passive range of motion in stages 2 and 3 of the adhesive capsulitis.

The results of this study show that the glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique applied after a limb cycle ergometer training, was effective in treating motion deficits commonly found in patients with AC, especially passive range of motion of external rotation. Our results are consistent with those in the literature [29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[44], where it can be seen that the range of external glenohumeral rotation increases significantly in the short and long term by applying a high-degree technique of joint mobilization in posterolateral direction, maintained and applied in the final range of motion.

However, there are at least two methodological aspects that differentiate this study from other randomized trials published. The first is that this study compares the glenohumeral posterior mobilization with conventional treatment; other studies have compared manual therapy techniques [32],[34], the same technique in different directions of application [31], or the addition of the technique to a treatment program [33],[34]. The second is that this study includes the irritability aspect in the selection of patients, as some studies have reported that there is a percentage of patients who do not tolerated well high-degree of mobilization techniques. It is important to consider that the glenohumeral posterior movement is a III-degree technique according to Kaltenborn, performed in the final range of available movement. Therefore, the technique is likely to be annoying and / or painful, especially in patients who present adhesive capsulitis, in which pain predominates over the limited range of motion. Because of this, it was relevant, within the exclusion criteria, to exclude patients with high irritability, who most likely would not have tolerated the technique optimally.

In this regard, in the randomized clinical study Vermeulen et al. [34] it was established an inclusion criteria of patients in phase 2 of the adhesive capsulitis, with an eight-month average of progression of symptoms. However, this study does not describe the tolerance of patients treated with high degree technique of mobilization and the reason why it had two turnovers in each study group.

The randomized trial of Johnson et al. [31], founded on their selection criteria, assumed that the patients in their study were between phases 2 to 4 according to Neviaser [4]. However, they reported that for the group treated with anterior mobilization, only three of the 10 patients had sufficient decrease of pain and passive range of motion to tolerate increased stretching force, as a result of the dose of the technique in the prone position. For the group treated with posterior mobilization, three of the eight patients tolerated the treatment. In the randomized clinical trial of Yang et al. [32], patients had an average of 20 weeks from the start of the symptoms. The authors note that one of the factors that influence the success of the technique is that the patients were in phase 2 according to Reeves [13].

Although they do not refer to tolerance, to the ninth week of treatment five of the 28 patients were lost. The poor performance is attributed to the mobilization technique in the middle range. In the randomized clinical trial of Yang et al. [33], patients had an average of 17 weeks from the onset of symptoms. For this reason, they were in the stage of stiffness according to Reeves [13]. There is no reference to the tolerance of the technique studied. Finally, in randomized clinical trial of Sharad [44], patients had an average of four and a half months from the onset of symptoms and they do not mention the tolerance of the patient to the manual therapy technique studied.

The effectiveness of high mobilization techniques is based on distension and elongation of periarticular structures that happens when a joint has been subjected into its maximum range of arthrokinematic motion [45]. This concept refers to the physical components of stress- strain curve, which studies the behavior of the tissue when it has been subjected to a load, demonstrating that its properties will vary progressing from an elastic phase to a plastic phase [35]. Complementary to this, it has been suggested that apart from the movement degree, it is also very important the type of load that the structure is subject to, considering the length and direction of movement, where the position of the joint is also of fundamental importance. In the case of glenohumeral posterior mobilization, it is applied to the glenohumeral joint at rest, maintaining a range of 40º of abduction. Then, an axial distraction begins to the inferior sense of the humerus (grade III according to Kaltenborn), which causes passive elongation of periarticular components. Through this, joint contact zones are minimized and from this, glide is added posteriorly in a sustained manner, generating maximum elongation of the posterior portion of the joint capsule [31], whose function is to limit the posterior movement of the humeral head in 40º- 45º of abduction [46].

The asymmetric capsular-ligamentous tension has great impact on the movement of the humeral head. Harryman et al. [47] was the first to report that tension of the rotator interval produced a reduction in inferior and posterior translational movements of the humeral head. After performing a cadaver study [48], they showed that tension of the rotators interval not only limits the range of glenohumeral movement, but also causes a forced translation of the humeral head in antero-superior direction. In this way, it limits the posterior translation associated with external rotation. Due to the role of the capsule in this disease, the concave-convex rule does not have great implication regarding the direction and/or the application of arthrokinematic movement of the different joint mobilization techniques [49]. For this reason, passive glide at the end range of motion performed in the sense of restriction (toward posterior) produces an immediate and significant improvement of the excursion range of the humeral head, getting an increase in rotational movement [31],[32],[33],[34].

Study limitations

The main limitation of the present study is the absence of follow-up after treatment ends, which does not allow establishing the effectiveness of both protocols in the medium and long term. The blinding of patients and physiotherapist, is impossible to perform considering the nature of the interventions studied. The results of this study cannot be extrapolated to patients with secondary adhesive capsulitis; clinical studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of this technique in this population.

Conclusions

The glenohumeral posterior mobilization applied after training with cycle ergometer is an effective short-term technique; it showed a significant increase of external rotation of the shoulder. This treatment also reduces pain and improves function compared to a conventional physiotherapy treatment, once completed 10 sessions of treatment in patients with primary adhesive capsulitis.

From the editor

This article was originally submitted in Spanish and was translated into English by the authors. The Journal has not copyedited this version.

Ethical aspects

The Journal has evidence that the study was approved by the Ethics and Scientific Committee of the Central Metropolitan Health Service, Santiago de Chile and that this committee approved the model of informed consent submitted by the authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have completed the conflict of interests declaration form from the ICMJE and declare not having any conflict of interests with the matter dealt herein. Forms can be requested from the responsible author or the editors.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of patients through the phases of the trial.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of patients through the phases of the trial.

Table 1. Baseline of patients with primary adhesive capsulitis in both groups treatment.

Table 1. Baseline of patients with primary adhesive capsulitis in both groups treatment.

Table 2. Summary results for variables measuring response to treatment.

Table 2. Summary results for variables measuring response to treatment.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

OBJECTIVE

To compare the short-term efficacy of a glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique versus conventional physiotherapy for the improvement of the range of external rotation in patients with primary adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder.

METHODS

This is a randomized clinical trial conducted at Hospital Clinico San Borja Arriaran in Chile. Fifty-seven patients with an age range of 50 to 58 years old were enrolled in two groups. Both groups were randomized to receive a treatment of 10 sessions: the experimental group (n=29) received a glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique after training with a cycle ergometer, and the control group (n=28) received conventional physiotherapy. The primary outcome measure was range of passive movement in external rotation; secondary outcomes were forward flexion and shoulder abduction, pain perception using the visual analogue scale and functionality test using the Constant-Murley Score.

RESULTS

The study had the statistical power to detect a difference of four degrees between the groups in the improvement of the range of external rotation at the end of the treatment period. The experimental group showed a significant improvement with a mean difference of 46.3 degrees (SD=8.7) compared to 18.1 (SD=7.2) in the control group (p<0.0001). There was also a decrease in the perception of pain (p= 0.0002) and improved function (p< 0.0001) in the group treated with glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique.

CONCLUSIONS

The glenohumeral posterior mobilization technique applied after training with cycle ergometer is an effective short-term technique to treat primary adhesive capsulitis decreasing the severity of pain and improving joint function compared with conventional physiotherapy treatment. The degree of increase in shoulder external rotation is more than 20 degrees beyond the increase achieved with conventional treatment.

Autores:

Héctor Joaquín Gutiérrez Espinoza[1,2], Francisco Pavez[1], Cristopher Guajardo[1], Manuel Acosta[3]

Autores:

Héctor Joaquín Gutiérrez Espinoza[1,2], Francisco Pavez[1], Cristopher Guajardo[1], Manuel Acosta[3]

Citación: Gutiérrez Espinoza HJ, Pavez F, Guajardo C, Acosta M. Glenohumeral posterior mobilization versus conventional physiotherapy for primary adhesive capsulitis: a randomized clinical trial. Medwave 2015 Sep;15(8):e6267 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2015.08.6267

Fecha de envío: 19/6/2015

Fecha de aceptación: 1/9/2015

Fecha de publicación: 22/9/2015

Origen: no solicitado

Tipo de revisión: con revisión por dos pares revisores externos, a doble ciego y un revisor estadístico

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Duplay S. De la periarthrite scapulohumerale. Rev Frat D Trav De Med. 1896; 53: 226.

Duplay S. De la periarthrite scapulohumerale. Rev Frat D Trav De Med. 1896; 53: 226.  Codman EA. The shoulder: rupture of the Supraspinatus tendon and other lesions in or about the subacromial bursa. Boston, MA: Thomas Todd Co; 1934:216-24

Codman EA. The shoulder: rupture of the Supraspinatus tendon and other lesions in or about the subacromial bursa. Boston, MA: Thomas Todd Co; 1934:216-24  Bateman JE. Neurologic painful conditions affecting the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983 Mar;(173):44-54. | PubMed |

Bateman JE. Neurologic painful conditions affecting the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983 Mar;(173):44-54. | PubMed | Neviaser RJ, Neviaser TJ. The frozen shoulder. Diagnosis and management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987 Oct;(223):59-64. | PubMed |

Neviaser RJ, Neviaser TJ. The frozen shoulder. Diagnosis and management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987 Oct;(223):59-64. | PubMed | Brue S, Valentin A, Forssblad M, Werner S, Mikkelsen C, Cerulli G. Idiopathic adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007 Aug;15(8):1048-54. | PubMed |

Brue S, Valentin A, Forssblad M, Werner S, Mikkelsen C, Cerulli G. Idiopathic adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007 Aug;15(8):1048-54. | PubMed | Hsu JE, Anakwenze OA, Warrender WJ, Abboud JA. Current review of adhesive capsulitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011 Apr;20(3):502-14. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hsu JE, Anakwenze OA, Warrender WJ, Abboud JA. Current review of adhesive capsulitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011 Apr;20(3):502-14. | CrossRef | PubMed | Neviaser JS. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a study of the pathological findings in periarthritis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1945;27(2):211-22. | Link |

Neviaser JS. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a study of the pathological findings in periarthritis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1945;27(2):211-22. | Link | Uhthoff HK, Boileau P. Primary frozen shoulder: global capsular stiffness versus localized contracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007 Mar;456:79-84. | PubMed |

Uhthoff HK, Boileau P. Primary frozen shoulder: global capsular stiffness versus localized contracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007 Mar;456:79-84. | PubMed | Zuckerman J, Cuomo F, Rokito S. Definition and classification of frozen shoulder: a consensus approach. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;(suppl): S72.

Zuckerman J, Cuomo F, Rokito S. Definition and classification of frozen shoulder: a consensus approach. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;(suppl): S72.  Zuckerman JD, Rokito A. Frozen shoulder: a consensus definition. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011 Mar;20(2):322-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Zuckerman JD, Rokito A. Frozen shoulder: a consensus definition. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011 Mar;20(2):322-5. | CrossRef | PubMed | Reeves B. The natural history of the frozen shoulder syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 1975;4(4):193-6. | PubMed |

Reeves B. The natural history of the frozen shoulder syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 1975;4(4):193-6. | PubMed | Hannafin JA, Chiaia TA. Adhesive capsulitis. A treatment approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000 Mar;(372):95-109. | PubMed |

Hannafin JA, Chiaia TA. Adhesive capsulitis. A treatment approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000 Mar;(372):95-109. | PubMed | Tveitå EK, Sandvik L, Ekeberg OM, Juel NG, Bautz-Holter E. Factor structure of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index in patients with adhesive capsulitis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008 Jul 17;9:103.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Tveitå EK, Sandvik L, Ekeberg OM, Juel NG, Bautz-Holter E. Factor structure of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index in patients with adhesive capsulitis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008 Jul 17;9:103.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Hand GC, Athanasou NA, Matthews T, Carr AJ. The pathology of frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007 Jul;89(7):928-32. | PubMed |

Hand GC, Athanasou NA, Matthews T, Carr AJ. The pathology of frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007 Jul;89(7):928-32. | PubMed | Kelley MJ, McClure PW, Leggin BG. Frozen shoulder: evidence and a proposed model guiding rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009 Feb;39(2):135-48. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kelley MJ, McClure PW, Leggin BG. Frozen shoulder: evidence and a proposed model guiding rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009 Feb;39(2):135-48. | CrossRef | PubMed | Struyf F, Meeus M. Current evidence on physical therapy in patients with adhesive capsulitis: what are we missing? Clin Rheumatol. 2014 May;33(5):593-600. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Struyf F, Meeus M. Current evidence on physical therapy in patients with adhesive capsulitis: what are we missing? Clin Rheumatol. 2014 May;33(5):593-600. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bulgen DY, Binder AI, Hazleman BL, Dutton J, Roberts S. Frozen shoulder: prospective clinical study with an evaluation of three treatment regimens. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984 Jun;43(3):353-60. | PubMed |

Bulgen DY, Binder AI, Hazleman BL, Dutton J, Roberts S. Frozen shoulder: prospective clinical study with an evaluation of three treatment regimens. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984 Jun;43(3):353-60. | PubMed | Diercks RL, Stevens M. Gentle thawing of the frozen shoulder: a prospective study of supervised neglect versus intensive physical therapy in seventy-seven patients with frozen shoulder syndrome followed up for two years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004 Sep-Oct;13(5):499-502.

| PubMed |

Diercks RL, Stevens M. Gentle thawing of the frozen shoulder: a prospective study of supervised neglect versus intensive physical therapy in seventy-seven patients with frozen shoulder syndrome followed up for two years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004 Sep-Oct;13(5):499-502.

| PubMed | Vastamäki H, Kettunen J, Vastamäki M. The natural history of idiopathic frozen shoulder: a 2- to 27-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Apr;470(4):1133-43. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Vastamäki H, Kettunen J, Vastamäki M. The natural history of idiopathic frozen shoulder: a 2- to 27-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Apr;470(4):1133-43. | CrossRef | PubMed | Mao CY, Jaw WC, Cheng HC. Frozen shoulder: correlation between the response to physical therapy and follow-up shoulder arthrography. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997 Aug;78(8):857-9. | PubMed |

Mao CY, Jaw WC, Cheng HC. Frozen shoulder: correlation between the response to physical therapy and follow-up shoulder arthrography. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997 Aug;78(8):857-9. | PubMed | Nicholson GG. The effects of passive joint mobilization on pain and hypomobility associated with adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1985;6(4):238-46. | PubMed |

Nicholson GG. The effects of passive joint mobilization on pain and hypomobility associated with adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1985;6(4):238-46. | PubMed | Binder AI, Bulgen DY, Hazleman BL, Roberts S. Frozen shoulder: a long-term prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984 Jun;43(3):361-4. | PubMed |

Binder AI, Bulgen DY, Hazleman BL, Roberts S. Frozen shoulder: a long-term prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984 Jun;43(3):361-4. | PubMed | Carette S, Moffet H, Tardif J, Bessette L, Morin F, Frémont P, et al. Intraarticular corticosteroids, supervised physiotherapy, or a combination of the two in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum.

2003 Mar;48(3):829-38. | PubMed |

Carette S, Moffet H, Tardif J, Bessette L, Morin F, Frémont P, et al. Intraarticular corticosteroids, supervised physiotherapy, or a combination of the two in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum.

2003 Mar;48(3):829-38. | PubMed | Jürgel J, Rannama L, Gapeyeva H, Ereline J, Kolts I, Pääsuke M. Shoulder function in patients with frozen shoulder before and after 4-week rehabilitation. Medicina (Kaunas). 2005;41(1):30-8. | PubMed |

Jürgel J, Rannama L, Gapeyeva H, Ereline J, Kolts I, Pääsuke M. Shoulder function in patients with frozen shoulder before and after 4-week rehabilitation. Medicina (Kaunas). 2005;41(1):30-8. | PubMed | Hjelm R, Draper C, Spencer S. Anterior-inferior capsular length insufficiency in the painful shoulder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996 Mar;23(3):216-22. | PubMed |

Hjelm R, Draper C, Spencer S. Anterior-inferior capsular length insufficiency in the painful shoulder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996 Mar;23(3):216-22. | PubMed | Roubal PJ, Dobritt D, Placzek JD. Glenohumeral gliding manipulation following interscalene brachial plexus block in patients with adhesive capsulitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996 Aug;24(2):66-77. | PubMed |

Roubal PJ, Dobritt D, Placzek JD. Glenohumeral gliding manipulation following interscalene brachial plexus block in patients with adhesive capsulitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996 Aug;24(2):66-77. | PubMed | Vermeulen HM, Obermann WR, Burger BJ, Kok GJ, Rozing PM, van Den Ende CH. End-range mobilization techniques in adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder joint: A multiple-subject case report. Phys Ther. 2000 Dec;80(12):1204-13. | PubMed |

Vermeulen HM, Obermann WR, Burger BJ, Kok GJ, Rozing PM, van Den Ende CH. End-range mobilization techniques in adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder joint: A multiple-subject case report. Phys Ther. 2000 Dec;80(12):1204-13. | PubMed | Johnson AJ, Godges JJ, Zimmerman GJ, Ounanian LL. The effect of anterior versus posterior glide joint mobilization on external rotation range of motion in patients with shoulder adhesive capsulitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007 Mar;37(3):88-99. | PubMed |

Johnson AJ, Godges JJ, Zimmerman GJ, Ounanian LL. The effect of anterior versus posterior glide joint mobilization on external rotation range of motion in patients with shoulder adhesive capsulitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007 Mar;37(3):88-99. | PubMed | Yang JL, Chang CW, Chen SY, Wang SF, Lin JJ. Mobilization techniques in subjects with frozen shoulder syndrome: randomized multiple-treatment trial. Phys Ther. 2007 Oct;87(10):1307-15. | PubMed |

Yang JL, Chang CW, Chen SY, Wang SF, Lin JJ. Mobilization techniques in subjects with frozen shoulder syndrome: randomized multiple-treatment trial. Phys Ther. 2007 Oct;87(10):1307-15. | PubMed | Yang JL, Jan MH, Chang CW, Lin JJ. Effectiveness of the end-range mobilization and scapular mobilization approach in a subgroup of subjects with frozen shoulder syndrome: a randomized control trial. Man Ther. 2012 Feb;17(1):47-52.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Yang JL, Jan MH, Chang CW, Lin JJ. Effectiveness of the end-range mobilization and scapular mobilization approach in a subgroup of subjects with frozen shoulder syndrome: a randomized control trial. Man Ther. 2012 Feb;17(1):47-52.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Vermeulen HM, Rozing PM, Obermann WR, le Cessie S, Vliet Vlieland TP. Comparison of high-grade and low-grade mobilization techniques in the management of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther.2006 Mar;86(3):355-68.

| PubMed |

Vermeulen HM, Rozing PM, Obermann WR, le Cessie S, Vliet Vlieland TP. Comparison of high-grade and low-grade mobilization techniques in the management of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther.2006 Mar;86(3):355-68.

| PubMed | Neumann DA. Getting Started. En: Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System. Foundations for Physical Rehabilitation. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:12-5.

Neumann DA. Getting Started. En: Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System. Foundations for Physical Rehabilitation. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:12-5.  Tveitå EK, Ekeberg OM, Juel NG, Bautz-Holter E. Range of shoulder motion in patients with adhesive capsulitis; intra-tester reproducibility is acceptable for group comparisons. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008 Apr 12;9:49.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Tveitå EK, Ekeberg OM, Juel NG, Bautz-Holter E. Range of shoulder motion in patients with adhesive capsulitis; intra-tester reproducibility is acceptable for group comparisons. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008 Apr 12;9:49.

| CrossRef | PubMed | McCormack HM, Horne DJ, Sheather S. Clinical applications of visual analogue scales: a critical review. Psychol Med. 1988 Nov;18(4):1007-19. | PubMed |

McCormack HM, Horne DJ, Sheather S. Clinical applications of visual analogue scales: a critical review. Psychol Med. 1988 Nov;18(4):1007-19. | PubMed | Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain. 1983 Sep;17(1):45-56. | PubMed |

Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain. 1983 Sep;17(1):45-56. | PubMed | Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987 Jan;(214):160-4. | PubMed |

Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987 Jan;(214):160-4. | PubMed | Roy JS, MacDermid JC, Woodhouse LJ. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the Constant-Murley score. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010 Jan;19(1):157-64. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Roy JS, MacDermid JC, Woodhouse LJ. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the Constant-Murley score. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010 Jan;19(1):157-64. | CrossRef | PubMed | Ho CY, Sole G, Munn J. The effectiveness of manual therapy in the management of musculoskeletal disorders of the shoulder: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2009 Oct;14(5):463-74. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ho CY, Sole G, Munn J. The effectiveness of manual therapy in the management of musculoskeletal disorders of the shoulder: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2009 Oct;14(5):463-74. | CrossRef | PubMed | Favejee MM, Huisstede BM, Koes BW. Frozen shoulder: the effectiveness of conservative and surgical interventions--systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2011 Jan;45(1):49-56. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Favejee MM, Huisstede BM, Koes BW. Frozen shoulder: the effectiveness of conservative and surgical interventions--systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2011 Jan;45(1):49-56. | CrossRef | PubMed | Jain TK, Sharma NK. The effectiveness of physiotherapeutic interventions in treatment of frozen shoulder/adhesive capsulitis: a systematic review. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2014;27(3):247-73.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Jain TK, Sharma NK. The effectiveness of physiotherapeutic interventions in treatment of frozen shoulder/adhesive capsulitis: a systematic review. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2014;27(3):247-73.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Sharad KS. A comparative study on the efficacy of end range mobilization techniques in treatment of adhesive capsulitis of Shoulder. Indian J Physiother Occupational Ther. 2011;5(3):28-31. | Link |

Sharad KS. A comparative study on the efficacy of end range mobilization techniques in treatment of adhesive capsulitis of Shoulder. Indian J Physiother Occupational Ther. 2011;5(3):28-31. | Link | Hsu AT, Chiu JF, Chang JH. Biomechanical analysis of axial distraction mobilization of the glenohumeral joint--a cadaver study. Man Ther. 2009 Aug;14(4):381-6. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hsu AT, Chiu JF, Chang JH. Biomechanical analysis of axial distraction mobilization of the glenohumeral joint--a cadaver study. Man Ther. 2009 Aug;14(4):381-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | Harsimran K, Ranganath G, Ravi SR. Comparing effectiveness of antero-posterior glides on shoulder range of motion in adhesive capsulitis – a pilot study. Indian J Physiother Occupational Ther. 2011;5(1):43-6. | Link |

Harsimran K, Ranganath G, Ravi SR. Comparing effectiveness of antero-posterior glides on shoulder range of motion in adhesive capsulitis – a pilot study. Indian J Physiother Occupational Ther. 2011;5(1):43-6. | Link | Harryman DT 2nd, Sidles JA, Harris SL, Matsen FA 3rd. The role of the rotator interval capsule in passive motion and stability of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992 Jan;74(1):53-66. | PubMed |

Harryman DT 2nd, Sidles JA, Harris SL, Matsen FA 3rd. The role of the rotator interval capsule in passive motion and stability of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992 Jan;74(1):53-66. | PubMed | Harryman DT 2nd, Sidles JA, Clark JM, McQuade KJ, Gibb TD, Matsen FA 3rd. Translation of the humeral head on the glenoid with passive glenohumeral motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990 Oct;72(9):1334-43. | PubMed |

Harryman DT 2nd, Sidles JA, Clark JM, McQuade KJ, Gibb TD, Matsen FA 3rd. Translation of the humeral head on the glenoid with passive glenohumeral motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990 Oct;72(9):1334-43. | PubMed | Brandt C, Sole G, Krause MW, Nel M. An evidence-based review on the validity of the Kaltenborn rule as applied to the glenohumeral joint. Man Ther. 2007 Feb;12(1):3-11. | PubMed |

Brandt C, Sole G, Krause MW, Nel M. An evidence-based review on the validity of the Kaltenborn rule as applied to the glenohumeral joint. Man Ther. 2007 Feb;12(1):3-11. | PubMed |