Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Palabras clave: COVID-19, health care access, health care system, information and communication technologies

Introduction

On March 19, 2020, a mandatory lockdown was imposed in Argentina due to the global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2.

Objectives

To explore the elderly’s healthcare experiences during the lockdown and the problems that may have arisen regarding accessibility to the healthcare system and emerging adaptations to medical care.

Methods

We coded the data using Atlas.ti 8 software and then triangled the analysis among researchers from different backgrounds. Finally, concept maps were developed and themes arising from these were described.

Results

Thirty-nine participants were interviewed from the metropolitan area in Buenos Aires from April to July of 2020. The main emerging themes were: 1) access to regularly scheduled consults, 2) access to chronic medication, 3) emergency consultations, and 4) the role of information and communication technologies. Accessibility to the healthcare system was compromised due to reduced outpatient consultations, affecting health checkups, diagnosis, and treatment. However, participants tried to keep their immunizations up to date. Information and communication technologies were used to fill digital prescriptions and online medical consultations. While this was a solution to many, others did not have access to these technologies or had trouble using them.

Conclusions

The global pandemic caused a reduction in outpatient medical consultations. Emerging needs originated new ways of carrying out medical consultations, mainly through information and communication technologies, which was a solution for many but led to the exclusion of others because of the preexisting technology gap.

|

Main messages

|

The number of people over 60 years of age is progressively increasing, such that by 2050 it is expected to globally escalate more than double (from 962 million in 2017 to 2,100 million in 2050)[1]. In Argentina, there are currently 6.7 million people over 60 years of age, representing 14.27% of the total population[2], with a predominantly urban profile[3],[4]. The pandemic produced by the new SARS-CoV-2 virus, which spectrum of disease COVID-19 ranges from mild (approximately 80%) to respiratory failure and death[5]. As of November 3, 2020, it affected 1,027,598 people in our country, including 32,106 deaths. It is challenging to estimate mortality of the disease, as it may vary testing strategies and methods in each population. However, the highest mortality is found in older adults, reaching up to 20% according to some estimates[5],[6].

In Argentina, on March 19, 2020, mandatory social and preventive isolation was decreed[7], which implies a suspension of non-essential activities to reduce the movement of individuals. In this way, an attempt was made to reduce the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and to “flatten the curve” of cases, particularly the most severe ones. The main objectives of this isolation were to avoid the collapse of the country’s health systems operational capacity and reduce new cases and deaths associated with the virus[8]. This new situation compromised access to health care after decreasing transportation options, a saturation of pharmacies, and difficult access to the health system[9].

The Argentine health system is subdivided into three defined subsectors: public, private, and social security, with little articulation and much overlapping. According to the last census, 36.1% of the population depended only on the public sector with no other form of coverage, 46.4% had social security coverage, and 10.6% had private insurance. The system provides universal access to the population in the Argentine territory, although the capacity to provide effective coverage of benefits is heterogeneous. It is also characterized by decentralization and inequity[10].

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that healthcare systems prioritize urgent visits and delay scheduled consultations to decrease the spread of COVID-19 in healthcare settings. As a result, there have been changes in the accessibility of the different healthcare providers[11]. As for the Argentine health system, due to the pandemic, health resources had to be redistributed and adapted to this new scenario. In the different hospitals of the country, the number of beds, ventilators, and human resources were increased.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention evidenced an underutilization of important medical services for patients with urgent and emergent non-COVID-19 health needs[11]. The World Health Organization (WHO), in its survey of 105 countries conducted between May and July 2020, found that all health services were affected, including essential services for communicable and noncommunicable diseases, mental health, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health, and nutrition. According to their data, emergency services were the least disrupted[12], which correlates with local studies[13]. This disruption was more prominent in low-income countries[12].

Due to the change in access to health services, the implementation of telemedicine played a vital role in patient care. In Argentina, telemedicine began to be officially implemented in the public health system in 2018 to create the “national digital health strategy,” which aims to interconnect information from all public sector agencies. In 2019, the Civil Association of Telemedicine of the Argentine Republic joined this system, incorporating information from the private sector coming from institutions that used telemedicine regularly. Finally, in 2020, the Federal Digital Health Plan was implemented, which aims to strengthen the policies promoted in 2018, but above all, implementing the digital prescription. This new addition to the legislation and the health system acted as a facilitator for regular users of these platforms or those who can easily adapt because they have daily use of technologies. However, for those outside this daily use, it acted as a barrier and distanced them from access to the health system, either because it hinders the consultation process or any other service that the patient requires. In this context, our research questions were as follows:

- What were the older adults’ experiences of accessing the healthcare system during a lockdown?

- What barriers and facilitators did they face?

Considering the challenges described concerning preventive isolation, we developed a qualitative study whose primary objective was to explore the experiences of older adults in relation to their health care during COVID-19 lockdown, issues in accessibility to the healthcare system, and emerging adaptations.

Details of the methods were described in the first article of the series. An action research design with a qualitative approach was chosen. The action research component was only partially implemented due to the lackluster response of the participants. This is described in more detail and at greater length in the first part of this paper. (publication in Medwave, “A qualitative study on the elderly and mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown in Buenos Aires, Argentina - Part 1”). The epistemic framework of our study is embedded in constructivism. Lewin conceived this design as a collective activity, as a reflexive social practice to bring about appropriate changes in the situation under study[14],[15],[16].

We invited adults over 60 years of age who live alone, or with a relative over 60 years of age, or with a relative within the risk groups for serious illness due to COVID-19 (people with heart or chronic respiratory diseases or immunosuppressed), or with a relative with a disability and who had access to a fixed or mobile telephone, in the metropolitan area (the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and Greater Buenos Aires), to participate by telephone. The invitation was snowballed through the collaboration of the participants themselves. Based on the interim analysis of the findings, the relevance of continuing to interview participants was evaluated. When we reached 39 participants, we considered that we had saturated the main cross-cutting themes of the work.

The research team consisted of teacher-researchers (family physicians and a sociologist), medical students, and external collaborators (medical students from another university and a psychologist). Teachers and students from the Instituto Universitario Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires and the Universidad Nacional de La Matanza participated.

Data collection was performed using semi-structured telephone interviews, which sought to explore emerging difficulties during lockdown and community support networks. The assessment of community support networks was part of the “action research” design. Barriers and facilitators to accessing the health system were also explored, and reliable information on COVID-19 was provided. Interviews varied in length (between 20 and 40 minutes, depending on the case). Notes and verbatim excerpts of the interviews were collected, associating them with the telephone number in the database, adding the interviewees’ first names and locality to map the individuals.

For the analysis, iterative work was carried out, moving back and forward when reviewing each step. The data obtained through the interviews were organized and classified into categories using an open coding system through the Atlas Cloud software. The steps for the analysis, in the manner of the bricoleur researcher according to Denzin[17], were organized in the three stages known as:

In this process, we follow Taylor-Bogdan[18], who calls these three moments of discovery, codification, and relativization in parallel, where the aim is to develop an in-depth understanding[19]. Triangulation was performed in coding processes (by successive independent reviews of the texts) and analysis between researchers using Atlas.ti 8 software.

Participants were informed about the characteristics of the study, and oral informed consent was obtained due to the limitations of lockdown. Peoples’ identity was protected in a password-protected database under the responsibility of the interviewer. The interviews were not recorded, and notes were taken during the interview, including verbatim quotations to preserve the privacy of the older adults and prioritizing rapport. The study was conducted in full compliance with international research ethics regulations. The protocol was evaluated by the Comité de Ética de Protocolos de Investigación Universitario del Instituto Universitario Hospital Italiano and approved (No. 0001-20).

The results were reported according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research[20].

Characteristics of the participants

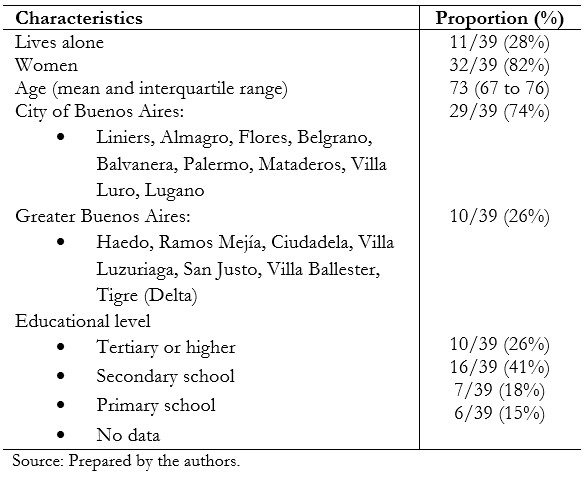

Thirty-nine participants from the City of Buenos Aires and Greater Buenos Aires were interviewed. Although we did not formally identify the data, participants were predominantly middle class. They had basic needs covered, were literate, and most had health coverage. The characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

All participants had a telephone line, either cellular or landline, which they were able to use. We observed that older adults who were actively working and used different technologies adapted more quickly to changes during the pandemic. Some participants felt the lack of technological resources due to difficulties in repairing technological tools, such as computers.

As for the health problems of our participants, a detailed characterization of their conditions was not performed. Most of them had chronic problems common in this population, such as hypertension or arthritis. In turn, several participants had a history of cancer. Two participants had psychiatric pathologies.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants.

In our current pandemic context, due to COVID-19, there were changes in the accessibility to the health system. As a common denominator, we found that in-person appointments were one of the most affected aspects of the healthcare system services because they were reduced due to the desire to prevent contagion and the spread of the virus. The fear of infecting or becoming infected (and consequently not having hospital beds available) was synergistic to the restrictions imposed by the circulation and the adaptations of the health system. In fact, health centers (outpatient care) were closed during the greater part of the isolation period:

“I needed a consultation with my rheumatologist because I was in a lot of pain, which is often chronic, and the clinic where she is seen was closed with no doctors on duty.” Woman, 79 years old.

This forced interviewees to travel to other centers, which was seen as a barrier for many.

“When they closed my center, they forced us to travel more. I can't travel by bus because my health isn't good, and now to go to the hospital, I have to spend $400 when going and $400 returning.” (For reference, the amount of a minimum pension in Argentina in June 2020 was approximately 18,000 Argentine pesos). Woman, 71 years old.

We will now describe the findings of our research in the following cross-cutting themes that emerged from the coding and analysis of the interviews:

1. Access to regularly scheduled consultations

The target population of our research usually suffers from chronic non-communicable diseases and requires regular consultations with emphasis on prevention and health promotion. The distance imposed by the pandemic and the conditions of isolation can be explained by several factors, mainly mediated by the fear of those who know themselves to have risk factors for the possibility of contagion. This fear correlates with the exponential growth of the number of cases, the possibility of becoming infected, and even more so when attending a health facility where the circulation of suspected and confirmed cases would be higher. At the same time, alternative methods appeared to access information and alleviate the doubts that arise during isolation.

“I don’t want to go to a hospital for anything, I had an appointment and I didn’t go because it was something simple, I take a vitamin chronically (...) I don’t want to go if I’m well and there is risk of getting infected (...) Then my shoulder hurts, but I don’t even go to the hospital.” Woman, 76 years old.

“As for check-ups, I have not yet had the need to go to the doctor. When I have doubts or something hurts I consult my nephew or my wife who is a nurse, she knows a lot too.” Man, 76 years old.

The participants had difficulties in getting an appointment with their usual physicians in person due to the current circumstances. Faced with this impossibility imposed on them, some preferred to consult with their usual doctors by other means; in this case, information and communication technologies helped the participants to access their consultations remotely.

“It affected me on the medical side because I wanted to make the consultation and I could not find face-to-face appointments, it was for the mastologist and they would not give me appointments (...).” Woman, 71 years old.

“I needed a consultation with my rheumatologist (...) the clinic where I was being treated was closed with no doctors on duty.” Woman, 71 years old.

“Every 15 days video call with the doctor to check up on me, in case my blood pressure suddenly drops.” Woman, 67 years old.

The care of mental health problems was compromised, considering the impact of the pandemic and the isolation in this area[21]. Notably, the control and follow-up of the most vulnerable individuals, such as those with preexisting psychiatric conditions, were affected. One of the participants, with a history of schizophrenia and who had a weak family support network, reported:

“My psychiatric treatment is null at the moment, the doctors didn’t give me appointments, my GP answers me, the psychiatrist doesn’t and that distresses me a lot.” Woman, 60 years old.

During the initial interview, she had told us that she had had an episode of self-harm at the beginning of home isolation, for which reason she had not gone to the hospital or sought immediate medical attention; but she had tried to contact her psychiatrist so that he could help her with the problems she was experiencing. Maintaining the ethical safeguards of the research, we urged early medical consultation and scheduled a follow-up interview. However, she did not answer the second call, and we learned from her relatives that she had committed suicide.

Another participant who had psychiatric care prior to isolation also reported problems with access. The alternative available at the time was through teleconsultation, and she did not handle the technologies well enough, thus encountering a barrier to accessing care.

“I would not attend an on-call unless an extreme situation requires it.” Woman, 63 years old.

The people interviewed belong to the risk group for whom the flu vaccine is indicated according to the recommendations of the Ministry of Health of Argentina. We found that the application of this was a frequent concern in our population of interviewees. While several were fearful about going out to get it, the vaccine was a priority.

“I had two concerns: one was to go to the traumatologist, which, well, you can’t; and the other was to be able to get the flu vaccine. And I went and got it, so I’m more relaxed.” Woman, 76 years old.

2. Access to chronic medication

Participants needed to renew their chronic medications, and some required new medications during the isolation period. Different ways of obtaining prescriptions for these were reported: through a photo of the prescription by the physician, sent by email or WhatsApp; through a health portal (computer system of social works and private medical companies for interaction with their affiliates); by access to a physical prescription to be picked up at an office; and, finally, through family members or physician friends.

Many of these means required the mastery of technology to obtain the necessary medication. Electronic prescriptions (entirely virtual) with getting the medication at a nearby pharmacy that works with the participants’ health insurer were the most commonly used methods. Obtaining new medication in the context of the pandemic and isolation brought additional problems. At first, there was uncertainty, considering that one could not circulate or go to health centers, about what means were available to obtain medication and, consequently, possible, overcoming solutions:

“At first I despaired because of the uncertainty I was living in. I didn’t know what I was going to do with the medication, as I couldn’t go and buy it.” Woman, 60 years old.

“I sent an email to the doctor and she sent me the prescription, I had no problems (...) The medication is sent to me by WhatsApp by the Dr., I show up with the card at the pharmacy and they give it to me without any problem. I go once a month.” Woman, 69 years old.

These testimonies show, once again, the importance of the role of technologies in the articulation of emerging problems during the pandemic, acting as facilitators. They also highlight family support, as younger family members have better use of these technologies and can travel to get their prescriptions.

“Because of diabetes I had to register with the Integral Medical Care Program by national law” (it is a type of state social security coverage for retirees, pensioners and the disabled). “I am amazed that everything was handled with the doctor by WhatsApp. They accepted the form and there was no problem. After a while I had my prescription filled and I bought it at the pharmacy nearby, I didn’t even have to print it out. I bought it free of charge.” Woman, 62 years old.

“I needed prescriptions to buy medicine and he wrote them for me, and my children brought them home. I count on them.” Female, 74.

An important factor was also the closer relationship with a physician friend or acquaintance, which was able to overcome the lack of familiarity with the technologies in some instances. However, it is important to consider that these prescriptions break with the continuity of care with their regular physician and are not accompanied by a formal evaluation.

“I have a doctor friend who manages my blood pressure and helps me a lot (...).” Woman, 79 years old.

“There are no social security pharmacies here, and my husband had to go to the pharmacy to buy medicines.” Woman, 79 years old.

Most of the medications required by our participants were for chronic disorders, such as diabetes, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and dyslipidemia. Participants reported feeling safer avoiding going out to pick up the prescription or medication, in expressions where caution about the risk of contagion is evident, and perhaps coupled with fear or anxiety—in some instances, leading to self-medication.

“We ask the doctor to send us the prescriptions to the pharmacy and I pick them up directly there, so I don’t make a double trip and expose myself!” Woman, 68 years old.

“I would have liked to go to the doctor, to the traumatologist because I have a problem with my sciatic, my waist; but I take anti-inflammatory medication until this is resolved.” Woman, 76 years old.

Finally, although in Argentina the elderly population is covered by one or more of the subsystems (private, social security, or public), access to medical prescriptions allows getting discounts that reduce out-of-pocket expenses (usually ranging between 40 and 50% of the value, depending on the medication, and for chronic medications, it is possible to get a discount of up to 100%). The pandemic and isolation blocked this mechanism:

“She has no social security or prepaid health insurance, so she only relies on the public system. She is hypertensive. She takes enalapril 20 milligrams. In lockdown, she did not go to any hospital or health center, so she did not have access to her medication free of charge or prescription. She bought it at a pharmacy at her own out-of-pocket expense.” Field note: lady without telephone.

3. Acute and emergent consultations

We identified different reasons why people chose to attend the on-call consultation, such as the treatment of a preexisting disease for which, prior to lockdown, they had gone to their treating physician to receive it. In other cases, the consultation was resolved by self-medication.

As an alternative to consultations at the emergency room or hospital, the use of the Emergency Medical Care System of the government of the City of Buenos Aires (through a system of ambulances, it provides a responsive service for the population’s emergencies) also emerges.

“I was on intravenous medication with my trusted rheumatologist. As I couldn’t get a doctor to see me, I ended up in an emergency room.” Woman, 76 years old.

“I would have liked to go to the doctor, to the traumatologist because I have a problem with my sciatic, my back; but I take anti-inflammatory medication until this is resolved.” Woman, 76 years old.

“On another occasion, I felt unwell and called the Emergency Medical Attention System of the Buenos Aires City Government, where I received medical attention that left me very satisfied.” Woman, 79 years old.

A particular circumstance were the consultations for symptoms compatible with COVID-19.

We found that there was fear and misinformation regarding the protocol to be followed, reflected in avoidant or inadequate behaviors. The attitudes of those who presented symptoms (three participants) were divergent. One participant presented with a sore throat and fever and decided to inform her employer, who paid for the test as her social security did not cover it. Another participant and her husband decided to call their health insurance company; they were tested at home the next day and complied with isolation. With symptoms and having traveled abroad at the beginning of the lockdown, the third participant presented fever and sore throat; but he preferred to wait and not to undergo the detection test to not appear in the government lists.

“I don’t want to consult. Can’t I assume I am infected without swabbing myself and doing the quarantine of one at home? (...) My fear is that, if they swab me and I test positive, they will take me to Tecnópolis.” Man, 69 years old.

Finally, regarding face-to-face consultations, these were subjectively judged for relevance—the patient’s expectations (search for a diagnosis or treatment) is in tension with the health system’s attempts to keep down viral circulation in care centers (open for essential services). This can be illustrated in a vignette described by a participant, where the doctor-patient relationship was severely affected:

“I wanted to make the appointment and I could not find face-to-face appointments, it was for the mastologist and they would not give me appointments. I solved it with a doctor from the sanatorium, but I saw that the doctors were exalted and one of them told me to make a video call through COVID-19. He was very aggressive and shouting. I understand that they are saturated and we are in uncertainty, but that way is not the right way. He yelled at me ‘you made a mistake, go and make an appointment online’. It was because I had snot and discomfort, plus a hardness in my breast” (she had breast cancer surgery several years ago). Woman, 71 years old.

4. The role of information and communication technologies

As mentioned previously, information and communication technologies played a key role in supporting consultations and access to chronic medication. This was particularly important in the containment of family physicians in situations where the patient’s prior knowledge facilitates their use:

“I had high blood pressure and emergency services came twice. My family doctor at the Italian Hospital says it is emotional, I always have high blood pressure at this time of year, it makes me sick that it is winter, that it gets dark early, plus the lockdown. Every 15 days I make a video call with the doctor to control myself, because if my blood pressure drops suddenly I lose potassium. It happened to me before and I do not want it to happen again while the contagions are growing. I ask for medication through the portal.” Female, 67 years old.

Due to the lack of skills in the management of new technologies, we identified barriers to implementing health care in this context.

“(Teleconsultations) That’s no good, I barely know how to handle a cell phone. What are they talking to me about?” Woman, 67 years old.

However, technologies were also used for consultations where the operational capacity of the system was exceeded.

“I called the cardiologist to make a video call. My chest was hurting a little bit.” Woman, 76 years old.

In addition, some of the people interviewed stated that consultation via telemedicine was not always sufficient, as they consider the physical examination a crucial tool for the understanding and diagnosis for which they consult.

“A friend of mine made one of these consultations; I asked her: – and what did the doctor do to you? – No, nothing, he asked me how I was doing. And that is useless ... You have to get checked, if they can’t physically check you, it’s not medicine”. Woman, 72 years old.

Main findings

From the interviews conducted, we were able to understand and report our participants’ experiences in the face of the adaptations and changes that took place in the Argentine health system, particularly in relation to accessibility. The suspension of face-to-face consultations, either due to the closure of healthcare centers or to changes in their services (providing only services on spontaneous demand or on-call), gave rise to the emergence of information and communication technologies. Although some technologies dominated, predominantly WhatsApp, most of the participants preferred face-to-face consultation, often pointing to barriers to its use. In this way, the need for digital literacy of older adults to reduce the inequity generated by the digital divide becomes present in this work.

We explored in the interviewees the information they had about COVID-19 and how the suspected or confirmed patient of this disease was managed. On several occasions, we detected poor quality information associated with fear and anxiety and led to avoidance behaviors when consulting the health system.

Relationship with other research

The lack of consultations for acute and severe pathologies decreases the possibility of timely treatment of these pathologies, impacting their morbidity and mortality. In a retrospective study in which a structured survey was carried out in 31 healthcare centers of the Association of Clinics, Sanatoriums and Private Hospitals of the Argentine Republic, and the Chamber of Diagnostic and Treatment Entities, it was found that emergency consultations and hospitalizations decreased. Admissions for angina pectoris, acute coronary syndrome, and cerebral vascular accidents also decreased[13]. Although we did not have participants who suffered objective consequences due to the lack of consultation, we did find specific situations of reduced contact with the healthcare system[22].

Regarding oncologic disease prevention behaviors, the Association of Clinics, Sanatoriums and Private Hospitals of the Argentine Republic, and the Chamber of Diagnostic and Outpatient Treatment Entities reported a drop in the number of screening studies performed during the pandemic[23]. This correlates with what we found in our interviews because many women could not go for mammography, for example, as a screening method. There is evidence that a 4-week delay in cancer diagnosis and treatment is associated with increased mortality in all common forms of cancer, and longer delays are increasingly detrimental[24]. A 2-year modeling study estimated a possible increase in mortality due to a decrease in mammograms, Pap smears, and video colonoscopies during isolation, as well as a delay in cancer treatment during the pandemic, whether with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or surgery[25].

In our research, particularly in the first part of the report, we observed an increase in mental illness in the context of the pandemic and isolation. Moreover, this need was not accompanied by a greater availability of support services. In fact, difficulties in accessing mental health specialists were reported. This coincides with what was identified by the WHO in a survey of 130 countries between June and August 2020, which showed that in more than 60% of the countries that took part in the survey, there were disturbances in the access to mental health services for the elderly (70%). In addition, 30% reported disturbances in access to medications to treat mental, neurological, and drug-use disorders[26]. In relation to chronic diseases, according to WHO, approximately half (53%) of the countries that took part in the survey reported severe, complete, or partial interruptions in hypertension management services[27], although our participants found alternatives to maintain treatments.

Participants valued the role of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination at an early stage of isolation. This is consistent with concerns regarding the possibility of COVID-19 co-infections leading to increased morbidity and mortality. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 and influenza share the same high-risk groups, including the elderly[27],[28],[29].

In Argentina, the National Ministry of Health decided to start with the application of the influenza vaccine to health personnel and the elderly, distributing more than 4 million influenza vaccines in the different provinces; then moving on to pregnant women and children from 6 months to 2 years of age[30]. Despite the recommendations, the sustained drop in vaccination coverage at the national level reached worrying levels, according to the National Ministry of Health[31]. In a study conducted in Spain, the applications of different vaccines have decreased between 5 and 60%, depending on the age and type of vaccine[32].

Self-medication is an aspect to take into account, given that some participants used this practice. Other studies at the national level and in countries of the region reported this phenomenon[33]. Although self-medication can be conceived as an additional self-care strategy[34], it is still a potentially dangerous practice due to the lack of information in the population. Therefore, it is an emerging problem that should not be underestimated, especially when the drugs used have potentially serious adverse effects. In addition, polymedication in this population is higher, so there is a greater possibility of interactions[35],[36].

Drug spending in the Argentine population may have changed to some extent in the lockdown period, the use of disinfectants and antiseptics increased, while medication for acute problems or not corresponding to chronic diseases saw a decrease in their purchase. Medication for chronic non-communicable diseases appears to have remained stable in our study population and the general population[37]. In our results, one participant had increased out-of-pocket expenditure on medication due to the impossibility of obtaining prescriptions, thus losing the discount from his social security. This could highlight the economic factor as a potential barrier to access to the healthcare system.

In our study, although teleconsultation was a widely used mean, it is worth clarifying that the context in which it was carried out forced the participants to consult by this means. When consulted, they agreed that face-to-face consultation, due to different circumstances, would have been their method of choice. However, the fact that this service was offered and that some could access their health check-ups does not mean that this was an entirely effective measure to bring them closer to the health system. Many of our participants chose not to continue with these controls, not for lack of willingness, but lack of access/training for the use of these resources, thus dismissing virtuality as an option.

In 2019, a group of researchers from the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires conducted a study on the use of telemedicine for the care of airway diseases during the epidemiological outbreak of 2018. That study concluded, like ours, that the elderly prefer to attend face-to-face consultation due to the difficulties that virtual communication entails for them, as they are not adapted to the use of technologies[38]. This coincidence in both is not surprising in view of the levels of digital literacy exposed in the journal Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean in April 2019[39]. In that publication, 24% of the adult population over 65 years of age in the Latin American region frequently use the Internet, in the best of cases, and a percentage close to half of the population has at least one computer at home. However, there is an effort to bring the elderly closer to technology in our country, for example, through the enactment of laws or the Universidad Para Adultos Mayores Integrados (University for Integrated Older Adults). Nonetheless, the supply of resources is not synonymous with reducing barriers, both in terms of technology and access to the health system. This is evident in the experiences of our participants.

For future research

Taking into account the limitations of our study, it is necessary to evaluate regional variations and the different implications in the different sectors of the Argentine health system (prepaid, social security, and public system) and thus assess whether our results can be extrapolated to different populations. Another point to consider is evaluating the most vulnerable or low-income subgroups that probably require more targeted strategies and who were not evaluated in this study. It is also important to explore the impact of telemedicine and how a hybrid system can be generated by implementing practices that can be most efficiently covered by technology. It is also essential to evaluate the impact of measures put on hold at the beginning of isolation, such as vaccination and screening. Another interesting point would be to study and measure the impact of infodemics and fake news on COVID-19 in this population.

Weaknesses and strengths

Our research has some limitations. First, our method of communication with participants was by telephone and could have left out people who were more isolated or did not use a telephone. In addition, prior to the call, we sometimes relied on WhatsApp to send a message and coordinate the time of the interview, including people with minimal use of information technologies. Second, although we had a second and even a third contact with some of the interviewees, there was only one encounter in the vast majority (75%), which could have affected the data collection for this research. Third, the participants were middle-class older adults from the metropolitan area who, for the most part, had social security health coverage (including the Comprehensive Health Care Program, PAMI) or private medicine, without exploring other social strata or people dependent exclusively on the public system. The transferability of our study is limited by the characteristics of the healthcare system and the organization of care for the elderly in an urban area. However, we believe that many adaptations, such as the emergence of telemedicine, can be extrapolated to other environments that implement it, especially the reality of Latin America, where health systems share the characteristic of being fragmented into social security, private medicine, and public providers. In turn, digital literacy and other needs of older adults with chronic conditions may be common to those of our participants.

Among the strengths of our study, it is possible to mention that we conducted a critical number of interviews with relevant information, which helped us carry out this work during the mandatory social isolation. We worked through weekly meetings where we discussed the data collected in the week’s interviews. We explored points of view considering geographic and gender diversity, and the interviewees felt comfortable sharing their experiences freely. We used a systematic methodology of recording and coding the data, and the analysis was handled by researchers from diverse backgrounds (medicine, psychology, and sociology). We processed the data expeditiously because we believe it may be helpful for future research and decision-making. The study was reported following international standards of transparency in qualitative research.

The COVID-19 pandemic generated a new scenario in which accessibility to the health system was affected at the expense of reduced access to face-to-face consultations.

The emerging needs forced the development of new care strategies, most of which focused on information and communication technologies.

Although this provided a solution for many older adults, it also generated new exclusions due to preexisting technological gaps.

Contribution roles

CAL, GB, RV: validation, formal analysis, research, resources, data curation, writing (reviews and edits), visualization. MG: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, research, resources, data curation, writing (reviews and edits), visualization, supervision. PP, JSA: Validation, research, writing (reviews and edits), data curation. XSPS: Conceptualization, methodology, research, validation, writing (revisions and edits), supervision, data curation. JVAF: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, research, writing (reviews and edits), validation, resourcing, data curation, visualization, project management, supervision, project management, and fund acquisition. DV: research, data curation, writing (revisions and edits).

Competing interests

The authors have completed the ICMJE conflict of interest declaration form and declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The forms can be requested by contacting the responsible author or the Journal’s editorial management.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding for this research. It was co-funded by the Universidad Nacional de la Matanza (Programa Vincular UNLaM, 2020 edition) and the Instituto Universitario del Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires.

Ethics

The study was conducted in full compliance with international research ethics regulations. The protocol was evaluated by the Ethics Committee of University Research Protocols of the Instituto Universitario Hospital Italiano and approved (No. 0001-20).

Language of submission

Spanish.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Introduction

On March 19, 2020, a mandatory lockdown was imposed in Argentina due to the global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2.

Objectives

To explore the elderly’s healthcare experiences during the lockdown and the problems that may have arisen regarding accessibility to the healthcare system and emerging adaptations to medical care.

Methods

We coded the data using Atlas.ti 8 software and then triangled the analysis among researchers from different backgrounds. Finally, concept maps were developed and themes arising from these were described.

Results

Thirty-nine participants were interviewed from the metropolitan area in Buenos Aires from April to July of 2020. The main emerging themes were: 1) access to regularly scheduled consults, 2) access to chronic medication, 3) emergency consultations, and 4) the role of information and communication technologies. Accessibility to the healthcare system was compromised due to reduced outpatient consultations, affecting health checkups, diagnosis, and treatment. However, participants tried to keep their immunizations up to date. Information and communication technologies were used to fill digital prescriptions and online medical consultations. While this was a solution to many, others did not have access to these technologies or had trouble using them.

Conclusions

The global pandemic caused a reduction in outpatient medical consultations. Emerging needs originated new ways of carrying out medical consultations, mainly through information and communication technologies, which was a solution for many but led to the exclusion of others because of the preexisting technology gap.

Autores:

Candela Agustina Loza[1], German Baez[1], Rodrigo Valverdi[2], Pedro Pisula[1], Julieta Salas Apaza[2], Vilda Discacciati[1], Mariano Granero[1], Ximena Salomé Pizzorno Santoro[3], Juan Víctor Ariel Franco[1,2]

Autores:

Candela Agustina Loza[1], German Baez[1], Rodrigo Valverdi[2], Pedro Pisula[1], Julieta Salas Apaza[2], Vilda Discacciati[1], Mariano Granero[1], Ximena Salomé Pizzorno Santoro[3], Juan Víctor Ariel Franco[1,2]

Citación: Loza CA, Baez G, Valverdi R, Pisula P, Salas Apaza J, Discacciati V, et al. A qualitative study on the elderly and accessibility to health services during the COVID-19 lockdown in Buenos Aires, Argentina - Part 2. Medwave 2021;21(4):e8192 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2021.04.8192

Fecha de envío: 2/12/2020

Fecha de aceptación: 13/4/2021

Fecha de publicación: 24/5/2021

Origen: No solicitado

Tipo de revisión: Revisión por pares externa, por cuatro árbitros a doble ciego

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population projected to reach 9.8 billion in 2050, and 11.2 billion in 2100. New York: UN DESA; 2017. [On line]. | Link |

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population projected to reach 9.8 billion in 2050, and 11.2 billion in 2100. New York: UN DESA; 2017. [On line]. | Link | Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos de la República Argentina. Censo 2010. Buenos Aires: INDEC; 2018. [On line]. | Link |

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos de la República Argentina. Censo 2010. Buenos Aires: INDEC; 2018. [On line]. | Link | Acosta LD. Factores asociados a la satisfacción vital en una muestra representativa de personas mayores de Argentina. Hacia promoc salud. 2019;24(1):56-69. | CrossRef |

Acosta LD. Factores asociados a la satisfacción vital en una muestra representativa de personas mayores de Argentina. Hacia promoc salud. 2019;24(1):56-69. | CrossRef | Tomaka J, Thompson S, Palacios R. The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. J Aging Health. 2006 Jun;18(3):359-84. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tomaka J, Thompson S, Palacios R. The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. J Aging Health. 2006 Jun;18(3):359-84. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Apr 7;323(13):1239-1242. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Apr 7;323(13):1239-1242. | CrossRef | PubMed | Livingston E, Bucher K. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA. 2020 Apr 14;323(14):1335. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Livingston E, Bucher K. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA. 2020 Apr 14;323(14):1335. | CrossRef | PubMed | Boletín oficial República Argentina. Aislamiento social preventivo y obligatorio, Decreto 297/2020. Buenos Aires; 2020. [On line]. | Link |

Boletín oficial República Argentina. Aislamiento social preventivo y obligatorio, Decreto 297/2020. Buenos Aires; 2020. [On line]. | Link | Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, Chapman A, Persad E, Klerings I, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Sep 15;9:CD013574. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, Chapman A, Persad E, Klerings I, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Sep 15;9:CD013574. | CrossRef | PubMed | Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020 May;5(5):e256. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020 May;5(5):e256. | CrossRef | PubMed | Palacios A, Espinola N, Rojas-Roque C. Need and inequality in the use of health care services in a fragmented and decentralized health system: evidence for Argentina. Int J Equity Health. 2020 Jul 31;19(1):67. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Palacios A, Espinola N, Rojas-Roque C. Need and inequality in the use of health care services in a fragmented and decentralized health system: evidence for Argentina. Int J Equity Health. 2020 Jul 31;19(1):67. | CrossRef | PubMed | Centers for disease control and prevention. Framework for Healthcare Systems Providing Non-COVID-19 Clinical Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. USA: CDC; 2020. [On line]. | Link |

Centers for disease control and prevention. Framework for Healthcare Systems Providing Non-COVID-19 Clinical Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. USA: CDC; 2020. [On line]. | Link | World health organization. Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim report, Aug 27 2020. Geneva: WHO; 2020. [On line]. | Link |

World health organization. Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim report, Aug 27 2020. Geneva: WHO; 2020. [On line]. | Link | Bozovich G, Alves de Lima A, Fosco M, Burgos LM, Martínez R, Dupuy de Lome R, et al. Daño colateral de la pandemia por covid-19 en centros privados de salud de Argentina. Medicina (Buenos Aires). 2020;80 Suppl III:37-4. [On line]. | Link |

Bozovich G, Alves de Lima A, Fosco M, Burgos LM, Martínez R, Dupuy de Lome R, et al. Daño colateral de la pandemia por covid-19 en centros privados de salud de Argentina. Medicina (Buenos Aires). 2020;80 Suppl III:37-4. [On line]. | Link | Colmenares AM, Piñero MA. La investigación acción: Una herramienta metodológica heurística para la comprensión y transformación de realidades y prácticas socio-educativas. Laurus. 2008;14(27):96–114. [On line]. | Link |

Colmenares AM, Piñero MA. La investigación acción: Una herramienta metodológica heurística para la comprensión y transformación de realidades y prácticas socio-educativas. Laurus. 2008;14(27):96–114. [On line]. | Link | Vidal Ledo M, Rivera Michelena N. Investigación-acción. Educ Med Super. 2007;21(4). [On line]. | Link |

Vidal Ledo M, Rivera Michelena N. Investigación-acción. Educ Med Super. 2007;21(4). [On line]. | Link | Díaz Llanes G. La investigación-acción en el primer nivel de atención. Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr. 2005;21(3-4). [On line]. | Link |

Díaz Llanes G. La investigación-acción en el primer nivel de atención. Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr. 2005;21(3-4). [On line]. | Link | Crozier G, Denzin N, Lincoln Y. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Br J Educ Stud. 1994 Dec;42(4):409. | CrossRef |

Crozier G, Denzin N, Lincoln Y. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Br J Educ Stud. 1994 Dec;42(4):409. | CrossRef | Taylor SJ, Bogdan R. Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación: la búsqueda de significados. 1 Ed. Buenos Aires: Paidós; 1987. 344 p. [On line]. | Link |

Taylor SJ, Bogdan R. Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación: la búsqueda de significados. 1 Ed. Buenos Aires: Paidós; 1987. 344 p. [On line]. | Link | Shaw E. A guide to the qualitative research process: evidence from a small firm study. Qualitative Market Research. 1999;2(2):59–70. | CrossRef |

Shaw E. A guide to the qualitative research process: evidence from a small firm study. Qualitative Market Research. 1999;2(2):59–70. | CrossRef | Smith L, Rosenzweig L, Schmidt M. Best Practices in the Reporting of Participatory Action Research: Embracing Both the Forest and the Trees 1Ψ7. Couns Psychol. 2010;38(8):1115–38. | CrossRef |

Smith L, Rosenzweig L, Schmidt M. Best Practices in the Reporting of Participatory Action Research: Embracing Both the Forest and the Trees 1Ψ7. Couns Psychol. 2010;38(8):1115–38. | CrossRef | Pisula P, Salas-Apaza JA, Báez GN, Loza CA, Valverdi R, Discacciati V, et al. A qualitative study on the elderly and mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown in Buenos Aires, Argentina - Part 1. Medwave. 2021;21(04):e8186. | CrossRef |

Pisula P, Salas-Apaza JA, Báez GN, Loza CA, Valverdi R, Discacciati V, et al. A qualitative study on the elderly and mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown in Buenos Aires, Argentina - Part 1. Medwave. 2021;21(04):e8186. | CrossRef | Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, Schmidt C, Garberich R, Jaffer FA, et al. Reduction in ST- Segment Elevation Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory Activations in the United States During COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jun 9;75(22):2871-2872. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, Schmidt C, Garberich R, Jaffer FA, et al. Reduction in ST- Segment Elevation Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory Activations in the United States During COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jun 9;75(22):2871-2872. | CrossRef | PubMed | Asociación de Clínicas, Sanatorios y Hospitales Privados de la República Argentina, Cámara de Entidades de Diagnóstico y Tratamiento Ambulatorio. La epidemia por coronavirus no elimina ni posterga otras enfermedades. El desafío de no caer en desatención. Buenos Aires: ADECRA CEDIM; 2020. [On line]. | Link |

Asociación de Clínicas, Sanatorios y Hospitales Privados de la República Argentina, Cámara de Entidades de Diagnóstico y Tratamiento Ambulatorio. La epidemia por coronavirus no elimina ni posterga otras enfermedades. El desafío de no caer en desatención. Buenos Aires: ADECRA CEDIM; 2020. [On line]. | Link | Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, Jalink M, Paulin GA, Harvey-Jones E, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020 Nov 4;371:m4087. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, Jalink M, Paulin GA, Harvey-Jones E, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020 Nov 4;371:m4087. | CrossRef | PubMed | Organización mundial de la salud. Los servicios de salud mental se están viendo perturbados por la COVID-19 en la mayoría de los países, según un estudio de la OMS. Ginebra: OMS; 2020. [On line]. | Link |

Organización mundial de la salud. Los servicios de salud mental se están viendo perturbados por la COVID-19 en la mayoría de los países, según un estudio de la OMS. Ginebra: OMS; 2020. [On line]. | Link | De Savigny D, Adam T, World Health Organization. Aplicación del pensamiento sistémico al fortalecimiento de los sistemas de salud. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [On line]. | Link |

De Savigny D, Adam T, World Health Organization. Aplicación del pensamiento sistémico al fortalecimiento de los sistemas de salud. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [On line]. | Link | Maltezou HC, Theodoridou K, Poland G. Influenza immunization and COVID-19. Vaccine. 2020 Sep 3;38(39):6078-6079. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Maltezou HC, Theodoridou K, Poland G. Influenza immunization and COVID-19. Vaccine. 2020 Sep 3;38(39):6078-6079. | CrossRef | PubMed | Dinleyici EC, Borrow R, Safadi MAP, van Damme P, Munoz FM. Vaccines and routine immunization strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Feb 1;17(2):400-407. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Dinleyici EC, Borrow R, Safadi MAP, van Damme P, Munoz FM. Vaccines and routine immunization strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Feb 1;17(2):400-407. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gobierno de Argentina. A partir de la semana que viene arranca la segunda etapa de vacunación antigripal. 2020. [On line]. | Link |

Gobierno de Argentina. A partir de la semana que viene arranca la segunda etapa de vacunación antigripal. 2020. [On line]. | Link | Ministerio de Salud de Argentina, Banco de Recursos de Comunicación. Sostenimiento de la vacunación de Calendario en contexto de pandemia. Argentina; 2020. [On line]. | Link |

Ministerio de Salud de Argentina, Banco de Recursos de Comunicación. Sostenimiento de la vacunación de Calendario en contexto de pandemia. Argentina; 2020. [On line]. | Link | Moraga-Llop FA, Fernández-Prada M, Grande-Tejada AM, Martínez-Alcorta LI, Moreno-Pérez D, Pérez-Martín JJ. Recuperando las coberturas vacunales perdidas en la pandemia de COVID-19 [Recovering lost vaccine coverage due to COVID-19 pandemic]. Vacunas. 2020 Jul-Dec;21(2):129-135. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Moraga-Llop FA, Fernández-Prada M, Grande-Tejada AM, Martínez-Alcorta LI, Moreno-Pérez D, Pérez-Martín JJ. Recuperando las coberturas vacunales perdidas en la pandemia de COVID-19 [Recovering lost vaccine coverage due to COVID-19 pandemic]. Vacunas. 2020 Jul-Dec;21(2):129-135. | CrossRef | PubMed | Quispe-Cañari JF, Fidel-Rosales E, Manrique D, Mascaró-Zan J, Huamán-Castillón KM, Chamorro–Espinoza SE, et al. Prevalence of Self-Medication during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Peru. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020. | CrossRef |

Quispe-Cañari JF, Fidel-Rosales E, Manrique D, Mascaró-Zan J, Huamán-Castillón KM, Chamorro–Espinoza SE, et al. Prevalence of Self-Medication during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Peru. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020. | CrossRef | Ruiz ME. Risks of self-medication practices. Curr Drug Saf. 2010 Oct;5(4):315-23. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ruiz ME. Risks of self-medication practices. Curr Drug Saf. 2010 Oct;5(4):315-23. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gouverneur A. Efectos adversos medicamentosos y farmacovigilancia. EMC - Tratado de Medicina. 2020;24(2):1-5. | CrossRef |

Gouverneur A. Efectos adversos medicamentosos y farmacovigilancia. EMC - Tratado de Medicina. 2020;24(2):1-5. | CrossRef | Malik M, Tahir MJ, Jabbar R, Ahmed A, Hussain R. Self-medication during Covid-19 pandemic: challenges and opportunities. Drugs Ther Perspect. 2020 Oct 3:1-3. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Malik M, Tahir MJ, Jabbar R, Ahmed A, Hussain R. Self-medication during Covid-19 pandemic: challenges and opportunities. Drugs Ther Perspect. 2020 Oct 3:1-3. | CrossRef | PubMed | Confederación farmacéutica Argentina. Pandemia, cuarentena y medicamentos para enfermedades crónicas – Segunda Parte. COFA; 2020. [On line]. | Link |

Confederación farmacéutica Argentina. Pandemia, cuarentena y medicamentos para enfermedades crónicas – Segunda Parte. COFA; 2020. [On line]. | Link | Frid SA, Ratti MFG, Pedretti A, Pollan J, Martínez B, Abreu AL, et al. Telemedicine for Upper Respiratory Tract Infections During 2018 Epidemiological Outbreak in South America. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019 Aug 21;264:586-590. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Frid SA, Ratti MFG, Pedretti A, Pollan J, Martínez B, Abreu AL, et al. Telemedicine for Upper Respiratory Tract Infections During 2018 Epidemiological Outbreak in South America. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019 Aug 21;264:586-590. | CrossRef | PubMed | Sunkel G, Ullmann H. Las personas mayores de América Latina en la era digital: superación de la brecha digita. Revista de la CEPAL. 2019;2019(127):243-68. | CrossRef |

Sunkel G, Ullmann H. Las personas mayores de América Latina en la era digital: superación de la brecha digita. Revista de la CEPAL. 2019;2019(127):243-68. | CrossRef |