Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Palabras clave: medical students, Guaraní language, knowledge

INTRODUCTION

Paraguay is a bilingual country and knowledge of the guarani language is an important communication tool for the doctor- patient relationship.

OBJECTIVE

To determine the degree of and the factors that influence the knowledge of the Guaraní language in medical students at a University Hospital in Paraguay

METHODS

Observational, cross-sectional, analytical study in which an anonymous questionnaire was applied to the final year medical students of a University Hospital of Paraguay. The baseline characteristics of the medical students and their degree of knowledge of the Guarani language were described. The association between the characteristics of the students and the degree of knowledge of the Guarani language was evaluated with the Chi square association test and the logistic regression model.

RESULTS

We included 264 students in the survey. Eighty two percent come from the capital, 72% made their pre-university studies in the capital; 92% studied Guaraní in primary and secondary education; 67.9% do not interpret Guarani correctly; 8.5% understand and express themselves totally in Guaraní. Of these, 86% refer to have the greater learning of the language in their home; 75.2% of respondents believe that primary and secondary education did not help in learning the language. The degree of knowledge of the language (speaks and understands the Guarani language correctly) varies according to: the origin of the student, the inland regions or the capital (31.25% vs. 2.5%, adjusted OR = 0.24, 95% confidence interval: 0.06 to 0.92, p = 0.003); the location of primary and secondary school: inland versus capital (25.6% vs. 1%, adjusted OR: 0.08, 95% confidence interval: 0.01 to 0.53, p = 0.009).

CONCLUSIONS

The degree of knowledge of the Guaraní language of the students is lower compared to the general population; those who best understand and express themselves were born or studied in the interior of the country. The majority considers that primary and secondary education contribute little in the learning of Guaraní. Since language is an important communication tool in the patient-doctor relationship and knowing that Guarani is the most spoken language in the country, strategies for its learning should be implemented.

The communication between doctor and patient plays an important role in the practice of medicine and is essential to provide a high quality medical care in terms of diagnosis and treatment as well as to emphasize different strategies for disease prevention in the general population [1],[2],[3].

Since 1992, the National Constitution declares Guaraní as the official language of Paraguay. Therefore, Paraguay is a bilingual country, with two official languages, Guaraní and Spanish. According to the 2002 census, 50% of the population declares to speak both languages, 37% only speaks Guaraní and 7% only Spanish [4]. A large percentage of the population who speaks only Guaraní lives in rural areas [5],[6],[7].

The knowledge of Guaraní language by health professionals in Paraguay could be important for a good communication with their patients, as well as for the detection of the problems they suffer, to determine the diagnosis and quickly provide the adequate treatment avoiding possible complications and even death, because the population that goes to the health services often speaks only in Guaraní [3]. In the interior of the country, according to the Population and Housing Census, the predominant language is Guaraní in 82.7% of households [7].

Several studies conducted on the impact of language on health care in the Latino population residing in the United States of America who do not speak English correctly, objectified that language is a factor associated with less access to health care, quality of attention and a worse general state of health of this population [8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[13], and recommended to health professionals to seek effective strategies to overcome this important barrier.

A previous study in nursing students showed that 31% of nursing students spoke and interpreted the Guaraní language correctly. In it, most of the students came from the interior of the country [5].

In Paraguay for centuries Guaraní has remained as an indigenous language, but not only of indigenous people. The Paraguayan society speaks Guaraní language from the colonial period to the present. Since its adoption as one of the two official languages of Paraguay, the Guaraní has become the goal of educational planning and policy, incorporating it as a teaching language with the aim of making every Paraguayan bilingual student in Spanish and Guaraní. Many problems arise in the implementation of formal education in Guaraní, including planning issues due to the lexicon, graphic, semantics and pragmatic application, as well as issues related to the different points of view of teachers about language teaching, programs of teacher training and program support [14].

The acceptance of human diversity and the application of policies of respect and tolerance have fostered instances, means and resources to facilitate multilingual communication. These experiences of intercultural and linguistic communication pose problems and challenges to be addressed. The installation and residence of multilingual and multicultural groups in the same society or community implies an effort to adapt beyond knowing the language of the other. If the doctor-patient communication is a challenge between those who share cultural contexts and speak the same language, much more so when the doctor and the patient come from different contexts and do not speak the same language. The act of interpreting the speaker of another language implies knowing and appropriating a structured reality, classified and configured according to a cultural worldview. This is not a simple task since it depends on a certain conception and action in the face of health and illness. Even in the same language, the demand may reflect different cultural conceptions of what the condition is. Confusion of meanings, untranslatability, prejudices, lack of empathy, deficient mastery of a language are facts and circumstances that hinder verbal communication, interrelation and interaction between health personnel and users. In the social structure, the health system is, together with the educational and judicial system, one of the areas most affected by this situation [15].

According to the available data, there are no studies of Guaraní language knowledge in medical students of Paraguay.

Thus, the primary objective of the present study was to determine the Guaraní language knowledge of the medical students in a Paraguay University Hospital. The secondary objective was to establish the factors that determine the Guaraní language knowledge degree of the students.

Design and stage

Observational, cross-sectional, analytical study in which medical students of Pediatrics Department of the Medicine Faculty of the National University of Asunción were analyzed by the method of anonymous survey with questionnaire.

Population and sampling

All the students of Pediatrics Department of the Medicine of the National University of Asunción, Paraguay in 2 no consecutive years (2010, 2014). Non-probabilistic sampling was done.

Measuring instrument and data collection

The survey was designed by the authors according to their experience in teaching and the observation of student communication with patients and reviewed by bilingual teachers of the institution.

There were 264 surveys, in which the following points were analyzed:

a) Are you sure if you correctly interpret the Guaraní language: (yes, no)

b) You understand Guaraní:

The data provided by the paper surveys were digitized initially to an Excel spreadsheet, afterwards after quality control they were exported and analyzed with the SPSS v20.0 program.

Analysis of data

A descriptive study of the basal characteristics of the medical students and the degree of knowledge of the Guaraní language of the students was carried out. The categorical variables were expressed in percentages. Analyzes were performed using the chi-square test to compare categorical variables. A logistic regression study was carried out with the following variables: (place of birth, locality of primary and secondary school, study of Guaraní in primary and secondary education) to determine factors associated with the degree of knowledge of the language. The results were considered significant for p <0.05.

Statistical analyzes were performed using the SPSS v20.0 program (Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the National University of Asunción approved the study and the informed consent of the medical students was obtained.

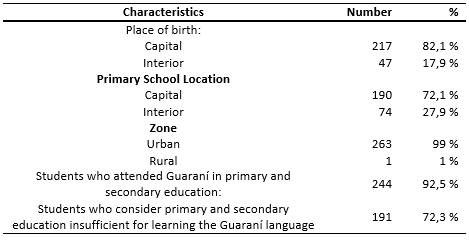

A total of 264 students were surveyed. 130 surveys were conducted in 2010 and 134 in 2014. 82% (217) comes from the capital of the country and 17.9% (47) from the interior. 72% (190) completed primary and secondary education in the capital area, 92% (244) of the respondents studied Guaraní during primary and secondary education (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of medical students. Origin and education.

Degree of knowledge of the Guaraní language

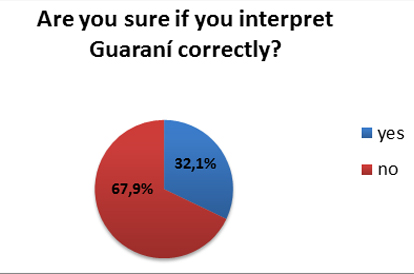

67.9% (179) of the respondents are not sure if they interpret Guaraní well (Figure 1).

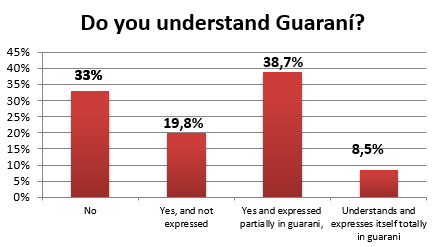

33% (87) does not understand or express in Guaraní; 19.7% (52) understands, but it is not expressed, 38.7% (102) understands and partially expressed and 8.5% (22) understands and expresses totally in Guaraní (Figure 2).

Of the respondents who understand and express themselves totally in Guaraní (8.5% of the total), 86% (17) reported that language acquisition was acquired at home with their parents.

72.3% (191) of the total respondents consider that primary and secondary education did not contribute to their learning of the Guaraní language (Table 1).

According to variable: if the student understands and expresses himself totally in Guaraní, there is a statistically significant difference in the language degree of knowledge If they come from the capital, 2.5% understand and express themselves totally in Guaraní with respect to those that come from the interior, where 31.25% understand and express themselves totally in Guaraní (p: 0.0001). Also, if the location of the student's primary school is from the capital, 1% understands and expresses himself totally in Guaraní vs. 25.6% if the location of the primary school is in the interior of the country (p: 0.0001).

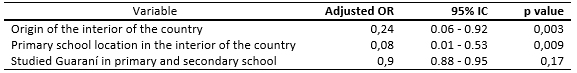

Factors that determine the degree of knowledge of the Guaraní language

As factors that determine the degree of knowledge (understands and is fully expressed in Guaraní) have been found significant: if the student comes from the interior or the capital (31.25% vs. 2.5%) (Adjusted OR: 0.24, interval 95% confidence interval from 0.06 to 0.92; p: 0.003); student's primary school location: interior vs. capital (25.6% vs. 1%) (Adjusted OR: 0.08, 95% confidence interval from 0.01 to 0.53, p: 0.009). It was not significant as a factor if the students studied Guaraní in primary and secondary education: Yes / No (8.6% vs. 0%) (Adjusted OR: 0.9, 95% confidence interval from 0.88 to 0.95, p: 0.17) (Table 2).

The main findings of our study are the following:

It is estimated that approximately 90% of Paraguay's general population is expressed in Guaraní correctly [4]. Guaraní is also the first language used by the majority of the population, especially in rural areas [7]. In our study, 67.9% of the students are not sure if they interpret the Guaraní language well and only 8.5% of the students understand and express themselves totally in Guaraní.

Effective communication between the patient and the health worker is essential for the provision of safe and high quality care. Any language barrier may affect patient -physician communication [16]. The inability to communicate effectively of a health worker harms patient access to the health system, weakens confidence in the quality of medical care received and decreases the likelihood that they will receive adequate follow-up. In addition, failure to cope with language barriers can result in misunderstandings such as problems with informed consent, inadequate understanding of diagnoses and treatments, dissatisfaction with care, avoidable morbidity and mortality, and interpretation of prescriptions. [17] In the health care sector, language barriers may decrease the physician's ability to determine patient symptoms and often result in an increase in the use of diagnostic resources or invasive procedures, inadequate treatment and diagnostic errors [18]. Poor communication with the patient is also a serious problem of patient safety and a common cause of adverse events in healthcare [19]. In a study conducted in the United States of America in pediatric patients from families with language barriers, a higher frequency of adverse events was observed, such as: errors in medication administration, erroneous or delayed diagnoses, lack of patient supervision, diagnostic procedures performed in the wrong patient, comparing with patients from families without a barrier in the language [20].

The main population studied in terms of the impact of the language for health care has been the Latina resident in the United States of America who does not speak English correctly. Three basic aspects of health care have been taken into account: 1) Access to the health system, 2) quality of health care and 3) the health status of this population. Most of the studies carried out showed that incorrect communication between doctor and patient is a predictor of poor access to health systems, a poorer quality of care and health status of this population [1]. This limitation also implies an increase in legal problems and an increase in health costs, which is why strategies to overcome this difficulty are promoted [21]. The professionalism of the doctor is related to his critical attitude, individual and social responsibility, empathy, with leadership in the healthcare team, competent, effective and safe, honest and trustworthy, committed to the patient and the organization, as well as a good communicator [22], among which is knowledge of the patient's language.

Our study shows a limitation in the communication of students in their future professional career as a tool to give a higher quality care to the general population, to prevent, diagnose and treat diseases.

In our study, unlike previous work carried out in nursing students [5], a lower degree of knowledge of the Guaraní language was observed, as well as that medical students came more frequently from the capital of the country.

In the present work it was observed that the students that come from the interior of the country have a significantly higher degree of knowledge of the language with respect to those of the capital. This situation is mainly due to the fact that the Guaraní language is culturally widely used outside the country's capital and they are more familiar with the language. In our study, 82.6% of the students come from the capital or surroundings, so the great majority is not in regular contact with the language during their university stage.

Since 1992, the teaching of the Guaraní language is compulsory in primary and secondary education to improve the knowledge of the language of the whole country [4]. In this study, 92.5% of the students studied Guaraní in their primary and secondary education, however, 75.2% of them consider this teaching insufficient to acquire adequate knowledge of the language and that it allows them to interact with patients. Although Guaraní is included in the curriculum as a language of instruction, it remains circumscribed in practice to "taught language". All the difficulties encountered by people who speak Guaraní, but who do not master the rules of their writing, feed the perception that they are not adapted to teaching. The monolingual Spanish-speaking children end up shying away from the Guaraní language, which is compulsory, taught as part of the bilingual education program. This difficulty is based on the fact that Guaraní is not historically the "language of school culture", that is, it was not configured as a "legitimate school language" [6].

The implications of this study reflect the importance of insisting on strategies to improve the teaching of language in basic education and also assess Guaraní teaching within the university academic program in careers as medicine to optimize the student's subsequent professional performance.

The limitations of this work are given by the small population, where the majority of students come from the capital of the country or its surroundings, although it is the oldest university with the highest number of doctors formed in Paraguay.

The knowledge degree of the Guaraní language of the medical students is lower compared to the general population; those who best understand and express themselves were born or studied in the interior of the country. The majority considers of little contribution the primary and secondary education for the learning of the Guaraní. Language is an important communication tool in the doctor - patient relationship and knowing that Guaraní is the most spoken language of the country, strategies for its correct learning should be implemented.

From the editor

The authors originally submitted this article in Spanish and subsequently translated it into English. The Journal has not copyedited this version.

Declaration of conflicts of interest

The authors have completed the ICMJE conflict of interest declaration form translated into Spanish by Medwave, and declare that they have not received funding for the report; have no financial relationships with organizations that might have an interest in the published article in the last three years; and have no other relationships or activities that could influence the published article. Forms can be requested by contacting the author responsible or the editorial management of the Journal.

Financing

The authors state that there was no source of external funding.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of medical students. Origin and education.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of medical students. Origin and education.

Figure 1. Knowledge of the Guaraní language in medical students at Universidad Nacional de Asunción, Paraguay (Are you sure if you interpret Guaraní correctly?

Figure 1. Knowledge of the Guaraní language in medical students at Universidad Nacional de Asunción, Paraguay (Are you sure if you interpret Guaraní correctly?

Figure 2. Knowledge of the Guaraní language in medical students National University of Asunción, Paraguay Do you understand Guaraní?

Figure 2. Knowledge of the Guaraní language in medical students National University of Asunción, Paraguay Do you understand Guaraní?

Table 2. Multivariate logistic regression model showing the factors for understanding and full expression in the Guaraní language of the study population.

Table 2. Multivariate logistic regression model showing the factors for understanding and full expression in the Guaraní language of the study population.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

INTRODUCTION

Paraguay is a bilingual country and knowledge of the guarani language is an important communication tool for the doctor- patient relationship.

OBJECTIVE

To determine the degree of and the factors that influence the knowledge of the Guaraní language in medical students at a University Hospital in Paraguay

METHODS

Observational, cross-sectional, analytical study in which an anonymous questionnaire was applied to the final year medical students of a University Hospital of Paraguay. The baseline characteristics of the medical students and their degree of knowledge of the Guarani language were described. The association between the characteristics of the students and the degree of knowledge of the Guarani language was evaluated with the Chi square association test and the logistic regression model.

RESULTS

We included 264 students in the survey. Eighty two percent come from the capital, 72% made their pre-university studies in the capital; 92% studied Guaraní in primary and secondary education; 67.9% do not interpret Guarani correctly; 8.5% understand and express themselves totally in Guaraní. Of these, 86% refer to have the greater learning of the language in their home; 75.2% of respondents believe that primary and secondary education did not help in learning the language. The degree of knowledge of the language (speaks and understands the Guarani language correctly) varies according to: the origin of the student, the inland regions or the capital (31.25% vs. 2.5%, adjusted OR = 0.24, 95% confidence interval: 0.06 to 0.92, p = 0.003); the location of primary and secondary school: inland versus capital (25.6% vs. 1%, adjusted OR: 0.08, 95% confidence interval: 0.01 to 0.53, p = 0.009).

CONCLUSIONS

The degree of knowledge of the Guaraní language of the students is lower compared to the general population; those who best understand and express themselves were born or studied in the interior of the country. The majority considers that primary and secondary education contribute little in the learning of Guaraní. Since language is an important communication tool in the patient-doctor relationship and knowing that Guarani is the most spoken language in the country, strategies for its learning should be implemented.

Autores:

Hassel Jimmy Jiménez[1], Lorena Delgadillo[1], Ana Campuzano de Rolon[1], Diana Jiménez[1], Angélica de Samudio[1], Adriana Agüero[2], César Radice[3], Gustavo Jiménez-Britez[4]

Autores:

Hassel Jimmy Jiménez[1], Lorena Delgadillo[1], Ana Campuzano de Rolon[1], Diana Jiménez[1], Angélica de Samudio[1], Adriana Agüero[2], César Radice[3], Gustavo Jiménez-Britez[4]

Citación: Jiménez HJ, Delgadillo L, Campuzano de Rolon A, Jiménez D, de Samudio A, Agüero A, et al. Knowledge of the Guarani language in medical students at a university hospital in Paraguay. Medwave 2018 Mar-Abr;18(2):e7200 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2018.02.7200

Fecha de envío: 5/11/2017

Fecha de aceptación: 12/2/2018

Fecha de publicación: 10/4/2018

Origen: no solicitado

Tipo de revisión: con revisión por dos pares revisores externos, a doble ciego

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Chang PH, Fortier JP. Language barriers to health care: an overview. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:5-20. | Link |

Chang PH, Fortier JP. Language barriers to health care: an overview. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:5-20. | Link | Timmins CL. The impact of language barriers on the health care of Latinos in the United States: a review of the literature and guidelines for practice. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2002 Mar-Apr;47(2):80-96. | PubMed |

Timmins CL. The impact of language barriers on the health care of Latinos in the United States: a review of the literature and guidelines for practice. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2002 Mar-Apr;47(2):80-96. | PubMed | Gómez Ayala AE. Inmigración y salud: asistencia sanitaria al niño inmigrante. Medwave 2009 May;9(5):e3923. | CrossRef |

Gómez Ayala AE. Inmigración y salud: asistencia sanitaria al niño inmigrante. Medwave 2009 May;9(5):e3923. | CrossRef | Quiñonez C. Diversidad Cultural e interculturalidad en el marco de la educación en formal en Paraguay. Rev Int Investig Cienc. Soc. 2012;8(1):7-23. | Link |

Quiñonez C. Diversidad Cultural e interculturalidad en el marco de la educación en formal en Paraguay. Rev Int Investig Cienc. Soc. 2012;8(1):7-23. | Link | Maidana A. Grado de conocimiento y uso del idioma guaraní de estudiantes en la interrelación con el usuario guaraní hablante (TESIS).Universidad Nacional de Asunción; 2011. [on line] | Link |

Maidana A. Grado de conocimiento y uso del idioma guaraní de estudiantes en la interrelación con el usuario guaraní hablante (TESIS).Universidad Nacional de Asunción; 2011. [on line] | Link | Ortiz Sandoval L. Bilinguismo y Educación: La diferenciación social de la lengua escolar. América Latina Hoy. 2012;60:139-150. | Link |

Ortiz Sandoval L. Bilinguismo y Educación: La diferenciación social de la lengua escolar. América Latina Hoy. 2012;60:139-150. | Link | Dirección General de Estadística, Encuestas y Censos (DGEEC) de la SecretaríaTécnica de Planificación de la Presidencia de la República del Paraguay. Principales Resultadosdel Censo 2002. Vivienda y Población. Asunción, Paraguay: dgeec publicaciones;2003. | Link |

Dirección General de Estadística, Encuestas y Censos (DGEEC) de la SecretaríaTécnica de Planificación de la Presidencia de la República del Paraguay. Principales Resultadosdel Censo 2002. Vivienda y Población. Asunción, Paraguay: dgeec publicaciones;2003. | Link | Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: a comparison of professional versus ad hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 Nov;60(5):545-53. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: a comparison of professional versus ad hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 Nov;60(5):545-53. | CrossRef | PubMed | Diamond LC, Luft HS, Chung S, Jacobs EA. "Does this doctor speak my language?" Improving the characterization of physician non-English language skills. Health Serv Res. 2012 Feb;47(1 Pt 2):556-69.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Diamond LC, Luft HS, Chung S, Jacobs EA. "Does this doctor speak my language?" Improving the characterization of physician non-English language skills. Health Serv Res. 2012 Feb;47(1 Pt 2):556-69.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Vela M, Fritz C, Jacobs EA. Establishing Medical Students' Cultural and Linguistic Competence for the Care of Spanish-Speaking Limited English Proficient Patients. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016 Sep;3(3):484-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Vela M, Fritz C, Jacobs EA. Establishing Medical Students' Cultural and Linguistic Competence for the Care of Spanish-Speaking Limited English Proficient Patients. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016 Sep;3(3):484-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | DeCamp LR, Kuo DZ, Flores G, O'Connor K, Minkovitz CS. Changes in language services use by US pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2013 Aug;132(2):e396-406. | CrossRef | PubMed |

DeCamp LR, Kuo DZ, Flores G, O'Connor K, Minkovitz CS. Changes in language services use by US pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2013 Aug;132(2):e396-406. | CrossRef | PubMed | Tocher TM, Larson EB. Do physicians spend more time with non-English-speaking patients? J Gen Intern Med. 1999 May;14(5):303-9. | PubMed |

Tocher TM, Larson EB. Do physicians spend more time with non-English-speaking patients? J Gen Intern Med. 1999 May;14(5):303-9. | PubMed | Woloshin S, Bickell NA, Schwartz LM, Gany F, Welch HG. Language barriers in medicine in the United States. JAMA. 1995 Mar 1;273(9):724-8. | PubMed |

Woloshin S, Bickell NA, Schwartz LM, Gany F, Welch HG. Language barriers in medicine in the United States. JAMA. 1995 Mar 1;273(9):724-8. | PubMed | Canese Caballero V. When Policy Becomes Practice: Teachers' Perspectives on Official Bilingualism and the Teaching of Guaraní as a Second Language in Paraguay. [THESIS]. Arizona State University. 2012. | Link |

Canese Caballero V. When Policy Becomes Practice: Teachers' Perspectives on Official Bilingualism and the Teaching of Guaraní as a Second Language in Paraguay. [THESIS]. Arizona State University. 2012. | Link | Figueroa-Saavedra M. Estrategias para superar las barreras idiomáticas entre el personal de salud-usuario de servicios de salud pública en España, Estados Unidos y México. Comunicación y sociedad. 2009;12:149-175. | Link |

Figueroa-Saavedra M. Estrategias para superar las barreras idiomáticas entre el personal de salud-usuario de servicios de salud pública en España, Estados Unidos y México. Comunicación y sociedad. 2009;12:149-175. | Link | Gregg J, Saha S. Losing culture on the way to competence: the use and misuse of culture in medical education. Acad Med. 2006 Jun;81(6):542-7. | PubMed |

Gregg J, Saha S. Losing culture on the way to competence: the use and misuse of culture in medical education. Acad Med. 2006 Jun;81(6):542-7. | PubMed | Koehn PH, Swick HM. Medical education for a changing world: moving beyond cultural competence into transnational competence. Acad Med. 2006 Jun;81(6):548-56. | PubMed |

Koehn PH, Swick HM. Medical education for a changing world: moving beyond cultural competence into transnational competence. Acad Med. 2006 Jun;81(6):548-56. | PubMed | Lie D, Boker J, Cleveland E. Using the tool for assessing cultural competence training (TACCT) to measure faculty and medical student perceptions of cultural competence instruction in the first three years of the curriculum. Acad Med. 2006 Jun;81(6):557-64. | PubMed |

Lie D, Boker J, Cleveland E. Using the tool for assessing cultural competence training (TACCT) to measure faculty and medical student perceptions of cultural competence instruction in the first three years of the curriculum. Acad Med. 2006 Jun;81(6):557-64. | PubMed | Weissman JS, Betancourt J, Campbell EG, Park ER, Kim M, Clarridge B, et al. Resident physicians' preparedness to provide cross-cultural care. JAMA. 2005 Sep 7;294(9):1058-67. | PubMed |

Weissman JS, Betancourt J, Campbell EG, Park ER, Kim M, Clarridge B, et al. Resident physicians' preparedness to provide cross-cultural care. JAMA. 2005 Sep 7;294(9):1058-67. | PubMed | Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, McPhillips H, Davis R. Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients? Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):575-9. | PubMed |

Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, McPhillips H, Davis R. Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients? Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):575-9. | PubMed | Hornberger J, Itakura H, Wilson SR. Bridging language and cultural barriers between physicians and patients. Public Health Rep. 1997 Sep-Oct;112(5):410-7. | PubMed |

Hornberger J, Itakura H, Wilson SR. Bridging language and cultural barriers between physicians and patients. Public Health Rep. 1997 Sep-Oct;112(5):410-7. | PubMed |