Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Palabras clave: scoping reviews as topic, literature review as topic, evidence-based medicine, systematic mapping

The increasing amount of evidence has caused an increasing amount of literature reviews. There are different types of reviews —systematic reviews are the best known—, and every type of review has different purposes. The scoping review is a recent model that aims to answer broad questions and identify and expose the available evidence for a broader question, using a rigorous and reproducible method. In the last two decades, researchers have discussed the most appropriate method to carry out scoping reviews, and recently the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guideline was published. This is the fifth article of a methodological collaborative series of narrative reviews about general topics on biostatistics and clinical epidemiology. This review aims to describe what scoping reviews are, identify their objectives, differentiate them from other types of reviews, and provide considerations on how to carry them out.

|

Key Points

|

The rapid increase in the generation of evidence in different areas, such as health or technology, triggered the need to group and synthesize this evidence in reviews. Systematic reviews are the most popular model because they reach potentially extrapolated conclusions by grouping all the available (and good quality) evidence for a specific clinical question with a rigorous and reproducible method [1]. They answer questions with the Population-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome (PICO) format. The development of health care towards a multidisciplinary science has led to more complex questions that do not meet the PICO format. These new questions may include:

New models of literature review emerged to answer these kinds of questions. They vary according to the type of question they aim to answer while maintaining the rigorousness and reproducibility of systematic reviews [1],[2].

Among these models, scoping reviews answer broad questions, and their production has increased considerably over the years, but more during the last decade [3],[4]. Most scoping reviews are related to health, followed by other social sciences and software engineering [3]. Public funds finance over 60% of scoping reviews, and most of them are developed by teams from North America and Europe [4].

This is the fifth article of a methodological series of narrative reviews about general topics on biostatistics and clinical epidemiology, which explore and summarize, in a friendly language, several published articles available in main databases and specialized reference texts. The series aims to reach undergraduate and graduate students. The Evidence-Based Medicine Team from the School of Medicine of Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile, collaborated with the Research department of Instituto Universitario Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina, and the UC Evidence Center, of the Universidad Católica, Chile, to elaborate the series. This article's main objective is to specify what scoping reviews are and when it is pertinent to conduct a scoping review and provide comments on their considerations and challenges.

Scoping reviews are extensive literature reviews that answer broad research questions. They focus on exploring the literature, establishing its size and potential scope in a specific area [2]. They show the general panorama rather than answer a specific question [1]. In addition, they follow a rigorous and systematic method that must be transparent and reproducible [5].

Since the inception of scoping reviews—in the late 90s—we lack a specific terminology for them [3],[4]. Scoping review is the most widely used; other terms such as "scoping study," "systematic mapping," or "scoping exercise" are also used [3].

Just as there is no specific terminology, there is no universal definition for scoping reviews. The most referenced definition is the one proposed by Mays et al. [6], and later used by Arksey and O'Malley [7], stating that scoping reviews "aim to map the key concepts rapidly underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available, and can be undertaken as stand-alone projects in their own right, especially where an area is complex or has not been reviewed comprehensively before" [6]. In this sense, scoping reviews are intended to be a comprehensive review of the literature: they must cover the greatest breadth of the available evidence, but the depth in the search may vary (depending on the objective of each review), which is why different sources can feed into scoping reviews, and both scientific articles and expert interviews are valid to the extent that they answer the research question [8].

Daudt et al. [9] suggested discarding the word "rapid" from the proposed definition since scoping reviews are not fast to perform, and they must be carried out conscientiously and in detail. They also state that the objectives of scoping reviews should be included in their definition (for example, to identify key concepts, gaps in the literature, and types and sources of evidence) to inform clinicians, policymakers, and researchers [9].

Scoping reviews can have different objectives, but they all share the goal of identifying and mapping the available evidence in a specific area. Some possible objectives are:

Example: A scoping review assessing and defining the location and the quality of the available evidence on emergency planning in the academic and grey literature of the United Kingdom [11].

Example: A scoping review exploring how physical training interventions affect the fat percentage of people with an intellectual deficit and assesses the need for further investigation [13].

Example: A scoping review summarizing the available recommendations on ophthalmologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic [14].

Example: A scoping review exploring and describing the available evidence on "occupational balance" (or the balance of work, rest, sleep, and play) and identifies the knowledge gaps [15].

Example: A scoping review that evaluates the definition of "bronchopulmonary dysplasia" in the available evidence and analyzes incidence variations according to the definition [16].

Example: A scoping review evaluating and narratively describing how researchers conduct scoping reviews [3].

Example: A scoping review identifying the features of primary health care models for indigenous people and later informs the best healthcare model of attention [17],[18].

The main objective of scoping reviews can combine two or more of the above mentioned. In our experience, the flexibility to incorporate several sources (clinical practice guidelines in our case) allowed us to reach a general picture of existing recommendations and identify gaps of evidence by assessing the reporting quality of each guideline [14].

What are the differences and similarities with other types of literature reviews?

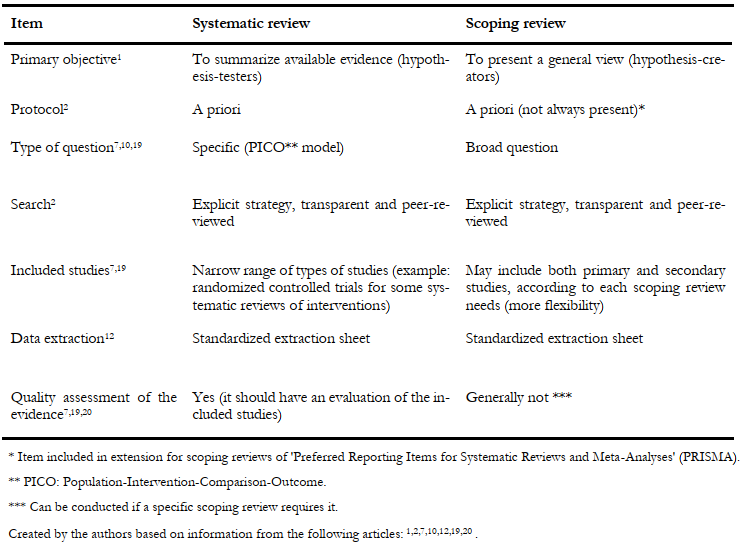

Systematic reviews are the literature reviews with the most extended trajectory and are widely used (and preferred) by decision-makers. In Table 1, we compare in detail scoping reviews with systematic reviews [12].

Table 1. Main differences between a systematic review and a scoping review.

Comparing scoping reviews with other literature reviews

Narrative reviews: It summarizes the evidence on a specific topic, but it can be subjective since the authors' experience, and previous knowledge or theories may guide the search and the synthesis of evidence. On the other hand, scoping reviews include a comprehensive and systematic search of the evidence (transparent and reproducible), and they extract and present the information in a structured form [2].

Evidence gap maps: They identify and analyze the gaps of evidence in the literature [21]. They are the most similar literature review to scoping reviews. They even share the extension of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for scoping reviews [22]. Their primary difference is that gap maps present a schematic and interactive figure (map) that shows where the available evidence on a specific topic is and where the gaps are [21].

Rapid reviews: It is a 'systematic review' that takes shortcuts in its methodology. They are efficient when resources or time are restrained, and decision-makers often request their production in specific situations [12],[23]. A rapid review tests a hypothesis rather than formulating it.

"Scoping reviews are easy to perform" or "Scoping reviews are a less rigorous method than a systematic review": Most scoping reviews do not assess quality nor perform quantitative synthesis of the evidence, which is why some people think that scoping reviews are easier to perform, or less rigorous than systematic reviews [7]. However, scoping reviews require researchers to critically assess information in order to present it. Also, they may include different types of studies, so literature search and literature screening yield many results that must be included, and this inherently challenges its conduction. Scoping reviews are not less rigorous than systematic reviews: they are a different model with their methodology and challenges [19].

"Scoping reviews are quick to perform": Perhaps the main reason for this myth is that the definition used by Arksey and O'Malley states that scoping reviews "aim to map rapidly" the literature [6],[7]. However, multiple factors may affect the speed when performing a scoping review: the question breadth, the amount of evidence reached, the time researchers can spend on each scoping review, and the number of researchers working on it. Pham et al. found that performing a scoping review takes from two weeks to 20 months when analyzing 344 scoping reviews [3]. Therefore, we cannot claim that they are fast to perform [9]. The estimated time to carry out a scoping review (and the time of researchers required) is an important variable to consider in a scoping review's cost [7].

There are different methods for conducting a scoping review. Arksey and O'Malley were the first to propose one, ensuring a rigorous and reproducible method to respond to the different scoping reviews' objectives [7]. Several authors suggested modifications to this original method to facilitate its application [8],[24],[25],[26], and, in 2015, the Joanna Briggs Institute published their methodology based on the original model and the ulterior suggestions [27], which has been well accepted [28]. This methodology was updated in 2020 and can be found in the chapter of scoping reviews in the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [29].

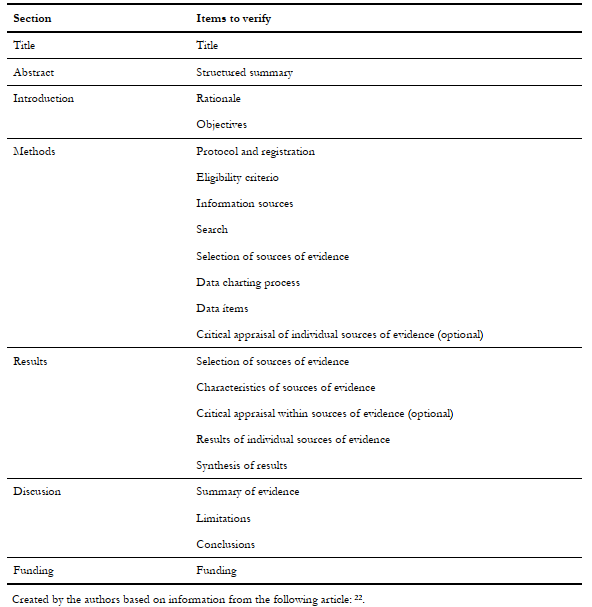

The PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) is the most recently published instrument to guide the scoping reviews' report [22]. It was based on the existing theoretical frameworks (previously mentioned), adding the comments and recommendations made to them. Multiple articles—preceding the publication of PRISMA-ScR—mentioned the need to standardize the methods of scoping reviews, enabling to evaluate their rigor, and to ensure a minimum level of analysis and report [3],[4],[8],[24],[26]: the PRISMA-ScR addresses these concerns. As mentioned above, PRISMA-ScR is also used to report evidence gap maps. Table 2 shows the PRISMA-ScR checklist; this extension excludes items from the original checklist (used for systematic reviews) and makes some items optional. For more information regarding this tool, we advise consulting it directly [22]. Given its recent release, there are still no publications that assess it (2018), but some published scoping reviews have already used this method, so soon we should expect to see users' opinions and recommendations [30].

Table 2. PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews checklist.

Although different theoretical frameworks to perform scoping reviews have been proposed during the last 20 years, PRISMA-ScR extension may be the guide to follow from now on. The different proposals kept common ideas that are important to highlight:

Scoping reviews must be carried out by a multidisciplinary team: By doing so, different disciplines complement each other [9]. Some authors state that scoping reviews should include a librarian (or information specialist) to develop high-quality search strategies [31]. The team should include at least two researchers [27], but according to some authors' experience, this number would not be enough, considering how laborious the work can be, and because a greater number of members from different disciplines enriches the work [9]. If possible, at least two independent researchers should perform the analysis (the same as other types of reviews).

The process must be iterative [7],[27]: The process should be carried out with rigor and reflectively, repeating steps if necessary to accomplish the objectives of the scoping review. The review should be comprehensive, so researchers must repeat the search at different moments when performing a scoping review (and this should be detailed in the methods section).

Search strategies and data extraction tables should be piloted before its use [4],[7]: The search strategies used in a scoping review should be able to provide all results to the (broad) question to be addressed. The search strategy must be piloted—even repeatedly—to ensure this. Researchers should also test the data extraction tables, as the results they produce should answer the question and satisfy the specific objectives of each scoping review.

What to consider when conducting a scoping review?

A balance between breadth and depth: Bibliographic searches of databases, specific platforms, gray literature, manual reviews, the information provided by experts, and even interviews (the latter in areas other than health) may nourish the evidence in a scoping review. It is essential to cover as much available information as possible (breadth); the depth, instead, will be determined by the question of each scoping review. The breadth could be a challenge: sometimes, the volume of evidence to review is so large that the predicted time, the languages covered, and the number of reviewers required to develop the scoping review is underestimated [4],[7]. In these cases, sometimes the reviewers may be able to assess less evidence than the total retrieved; this is a limitation because, despite being reported (maintaining transparency), it is contradictory with the main aim of scoping reviews: to have a general panorama of all the available information. This balance between breadth and depth is easier to achieve—and thus a briefer scoping review—in areas where the existing evidence is scarce [12].

Evidence quality assessment: It is not mandatory to assess the quality of the evidence, but reviewers may carry it out if it is the aim of their scoping review. Some authors state that not assessing the quality of the evidence may be a limitation of scoping reviews [2],[3],[12],[19]. When reviewers do not assess the quality of evidence, they may fail to identify evidence gaps where there is evidence of low quality. This could be a problem in scoping reviews that aim to support or inform decision-making in healthcare since they would not identify gaps where evidence exists, or because it is of low or very low quality, and further studies are needed.

Consultation with experts or key informants: This step of scoping reviews has not yet been fully defined [24] and is considered optional [7]. This stage has many possible interpretations, such as: the experts can provide additional references [7]; the experts may revise the preliminary data of a scoping review, evaluating its validity or utility [4]. Both are valid interpretations and imply the participation of external agents in the review in different moments of its performance, thus reflecting the lack of development on this matter.

Standardization of the process and report: The use of PRISMA-ScR ensures the rigor of the report when conducting scoping reviews. PRISMA-ScR will increase readers' confidence in the presented information and allows them to read these articles critically [32].

Scoping reviews are a recent method of literature review. They answer broad research questions aiming to identify and map the available evidence for a specific area, accomplishing the specific objectives of each review. They differ from other types of literature reviews mainly in their objectives and the type of question they address, but they share the rigorous and reproducible method of systematic reviews. There are different standards for reporting scoping reviews, but the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) is the newest and considers suggestions and critics made to previous guidelines.

Contributions of the authors

CV, LVM: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing, writing – review, visualization, supervision, project administration. LTB, BSM, MVP, ASD: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing, writing – review. ASD: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing, writing – review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors have no funding to report.

From the editors

The original version of this article was submitted in Spanish, which was the peer-reviewed version. This is a translation of the article submitted by the authors and has been lightly copyedited by the journal.

Table 1. Main differences between a systematic review and a scoping review.

Table 1. Main differences between a systematic review and a scoping review.

Table 2. PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews checklist.

Table 2. PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews checklist.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

The increasing amount of evidence has caused an increasing amount of literature reviews. There are different types of reviews —systematic reviews are the best known—, and every type of review has different purposes. The scoping review is a recent model that aims to answer broad questions and identify and expose the available evidence for a broader question, using a rigorous and reproducible method. In the last two decades, researchers have discussed the most appropriate method to carry out scoping reviews, and recently the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guideline was published. This is the fifth article of a methodological collaborative series of narrative reviews about general topics on biostatistics and clinical epidemiology. This review aims to describe what scoping reviews are, identify their objectives, differentiate them from other types of reviews, and provide considerations on how to carry them out.

Autores:

Catalina Verdejo[1], Luis Tapia-Benavente[1], Bastián Schuller-Martínez[1], Laura Vergara-Merino[1,2], Manuel Vargas-Peirano[2], Ana María Silva-Dreyer[2]

Autores:

Catalina Verdejo[1], Luis Tapia-Benavente[1], Bastián Schuller-Martínez[1], Laura Vergara-Merino[1,2], Manuel Vargas-Peirano[2], Ana María Silva-Dreyer[2]

Citación: Verdejo C, Tapia-Benavente L, Schuller-Martínez B, Vergara-Merino L, Vargas-Peirano M, Silva-Dreyer AM. What you need to know about scoping reviews. Medwave 2021;21(02):e8144 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2021.02.8144

Fecha de envío: 28/10/2020

Fecha de aceptación: 16/3/2021

Fecha de publicación: 30/3/2021

Origen: No solicitado

Tipo de revisión: Con revisión por pares externa, por dos árbitros a doble ciego

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P. All in the Family: systematic reviews, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and more. Syst Rev. 2015 Dec 22;4:183. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P. All in the Family: systematic reviews, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and more. Syst Rev. 2015 Dec 22;4:183. | CrossRef | PubMed | Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009 Jun;26(2):91-108. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009 Jun;26(2):91-108. | CrossRef | PubMed | Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014 Dec;5(4):371-85. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014 Dec;5(4):371-85. | CrossRef | PubMed | Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016 Feb 9;16:15. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016 Feb 9;16:15. | CrossRef | PubMed | Harms MC, Goodwin VA. Scoping reviews. Physiotherapy. 2019 Dec;105(4):397-398. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Harms MC, Goodwin VA. Scoping reviews. Physiotherapy. 2019 Dec;105(4):397-398. | CrossRef | PubMed | Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. Synthesising research evidence. In: Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, et al., eds. Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: Research methods. London: Routledge 2001.

Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. Synthesising research evidence. In: Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, et al., eds. Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: Research methods. London: Routledge 2001.  Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. | CrossRef |

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. | CrossRef | Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009 Oct;46(10):1386-400. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009 Oct;46(10):1386-400. | CrossRef | PubMed | Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013 Mar 23;13:48. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013 Mar 23;13:48. | CrossRef | PubMed | Khalil H, Peters MD, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Alexander L, McInerney P, et al. Conducting high quality scoping reviews-challenges and solutions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021 Feb;130:156-160. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Khalil H, Peters MD, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Alexander L, McInerney P, et al. Conducting high quality scoping reviews-challenges and solutions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021 Feb;130:156-160. | CrossRef | PubMed | Challen K, Lee AC, Booth A, Gardois P, Woods HB, Goodacre SW. Where is the evidence for emergency planning: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2012 Jul 23;12:542. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Challen K, Lee AC, Booth A, Gardois P, Woods HB, Goodacre SW. Where is the evidence for emergency planning: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2012 Jul 23;12:542. | CrossRef | PubMed | Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018 Nov

19;18(1):143. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018 Nov

19;18(1):143. | CrossRef | PubMed | Casey AF, Rasmussen R. Reduction measures and percent body fat in individuals with intellectual disabilities: a scoping review. Disabil Health J.

2013 Jan;6(1):2-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Casey AF, Rasmussen R. Reduction measures and percent body fat in individuals with intellectual disabilities: a scoping review. Disabil Health J.

2013 Jan;6(1):2-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Vargas-Peirano M, Navarrete P, Díaz T, Iglesias G, Hoehmann M. Care of ophthalmological patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid scoping review. Medwave. 2020 May 13;20(4):e7902. Spanish, English. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Vargas-Peirano M, Navarrete P, Díaz T, Iglesias G, Hoehmann M. Care of ophthalmological patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid scoping review. Medwave. 2020 May 13;20(4):e7902. Spanish, English. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wagman P, Håkansson C, Jonsson H. Occupational Balance: A Scoping Review of Current Research and Identified Knowledge Gaps. Journal of Occupational Science 2015;22:160–9. | CrossRef |

Wagman P, Håkansson C, Jonsson H. Occupational Balance: A Scoping Review of Current Research and Identified Knowledge Gaps. Journal of Occupational Science 2015;22:160–9. | CrossRef | Hines D, Modi N, Lee SK, Isayama T, Sjörs G, Gagliardi L, et al. Scoping review shows wide

variation in the definitions of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants and calls for a consensus. Acta Paediatr. 2017 Mar;106(3):366-374. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hines D, Modi N, Lee SK, Isayama T, Sjörs G, Gagliardi L, et al. Scoping review shows wide

variation in the definitions of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants and calls for a consensus. Acta Paediatr. 2017 Mar;106(3):366-374. | CrossRef | PubMed | Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, Brown N. Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Global Health. 2018 Jan 25;14(1):12. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, Brown N. Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Global Health. 2018 Jan 25;14(1):12. | CrossRef | PubMed | Harfield S, Davy C, Kite E, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown N, et al. Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care models of service delivery: a

scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015 Nov;13(11):43-51. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Harfield S, Davy C, Kite E, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown N, et al. Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care models of service delivery: a

scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015 Nov;13(11):43-51. | CrossRef | PubMed | Brien SE, Lorenzetti DL, Lewis S, Kennedy J, Ghali WA. Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implement Sci. 2010 Jan 15;5:2. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Brien SE, Lorenzetti DL, Lewis S, Kennedy J, Ghali WA. Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implement Sci. 2010 Jan 15;5:2. | CrossRef | PubMed | Peterson J, Pearce PF, Ferguson LA, Langford CA. Understanding scoping reviews: Definition, purpose, and process. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017 Jan;29(1):12-16. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Peterson J, Pearce PF, Ferguson LA, Langford CA. Understanding scoping reviews: Definition, purpose, and process. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017 Jan;29(1):12-16. | CrossRef | PubMed | Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016 Feb 10;5:28. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016 Feb 10;5:28. | CrossRef | PubMed | Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 2;169(7):467-473. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 2;169(7):467-473. | CrossRef | PubMed | Hamel C, Michaud A, Thuku M, Skidmore B, Stevens A, Nussbaumer-Streit B, et al. Defining Rapid Reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021 Jan;129:74-85. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hamel C, Michaud A, Thuku M, Skidmore B, Stevens A, Nussbaumer-Streit B, et al. Defining Rapid Reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021 Jan;129:74-85. | CrossRef | PubMed | Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010 Sep 20;5:69. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010 Sep 20;5:69. | CrossRef | PubMed | Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res Policy Syst. 2008 Jul 9;6:7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res Policy Syst. 2008 Jul 9;6:7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014 Dec;67(12):1291-4. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014 Dec;67(12):1291-4. | CrossRef | PubMed | Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015 Sep;13(3):141-6. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015 Sep;13(3):141-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | Khalil H, Bennett M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Peters M. Evaluation of the JBI scoping reviews methodology by current users. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2020 Mar;18(1):95-100. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Khalil H, Bennett M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Peters M. Evaluation of the JBI scoping reviews methodology by current users. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2020 Mar;18(1):95-100. | CrossRef | PubMed | Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI, 2020. | CrossRef |

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI, 2020. | CrossRef | McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, Langlois EV, O'Brien KK, Horsley T, et al. Reporting scoping reviews-PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020 Jul;123:177-179. | CrossRef | PubMed |

McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, Langlois EV, O'Brien KK, Horsley T, et al. Reporting scoping reviews-PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020 Jul;123:177-179. | CrossRef | PubMed |