Introduction

Cohort studies are observational designs that follow a group of subjects with one or more common characteristics over time. These designs involve periodic measurements to check for the occurrence of an outcome, event, or disorder which is being studied1-4. The term has a historical origin: in the Roman legions, six centuriae of soldiers marching in the battle field toward various destinations were given the name cohorts (cohors). The destinations varied depending on the group to which they belonged2,5. This is very similar to what occurs in this type of design, wherein groups of individuals advance toward an outcome, and the frequency can be determined by one or more factors to which they are exposed.

The design of a cohort study is similar to that of a clinical trial, which is considered to be the most suitable for causal inference13. One major difference, however, is that exposure occurs naturally, since it is determined by preferences, clinical decisions, or other conditions. In clinical trials, the latter is directly assigned by the researcher6.

From this viewpoint, cohorts are considered to be prospective and analytical designs2,3. Nevertheless, it is also possible to find retrospective versions where researchers gather existing data among patients that have or have not shown an outcome. As there is a follow-up process after exposure to an event, the cohort denomination also applies to this last design. The big difference between case studies and controls is that the cohorts which are to be contrasted are separated on the basis of exposure to a factor, instead of the outcome. A third variant, the ambidirectional cohort, implies gathering data in two directions: existing data is taken in, from clinical records, for example, and then complemented by patient follow-up until an event develops.

Both cohorts should be similar in every relevant aspect, which is very difficult to achieve in these studies due to their observational nature. This means they are susceptible to confusion bias, wherein other variables, which are different to the exposure being studied, could explain the results6.

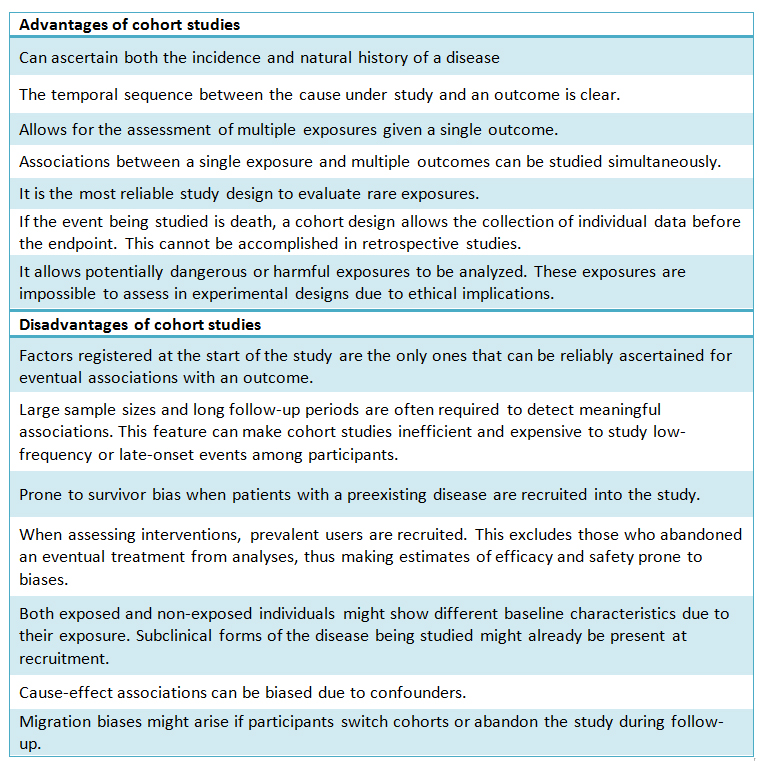

Table I provides a comparison between positive aspects and the complexities of cohort design.

Table 1. Comparative table. Advantages/disadvantages of a cohort study design.

Selecting the sample

The proper selection of participants, the rigorous recording of possible exposure factors, and the regular and objective control of the occurrence of events constitute the key to the proper development of this type of study2-4.

The individuals may belong to a general population, as in the Framingham study that contributed key information on cardiovascular risk factors14-26, or specific social groups7-9,11,12, such as a cohort of 40,633 English physicians that established a link between smoking and various events of interest10,27-33.

A cohort can also be selected on account of a specific type of exposure, such as environmental pollution, radiation, or occupational hazards. In these cases, that is to say, studies that cannot be assessed experimentally due to ethical reasons, this design proves ideal4.

Quality-related aspects

The first aspect to be assessed in a cohort study is the similarity of the contrasted groups. This is achieved with a table of characteristics of the individuals being studied, which should be reported in any study of this type. In the event of imbalances, certain statistic techniques for multivariate analysis, such as regressions, can make it possible to adjust the analysis to account for the differences among groups.

In September 2004 a panel of experts issued a consensus checklist for reporting observational studies, known as STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology). The checklist includes items such as title, abstract, introduction, methods, results and discussion sections for articles35. The STROBE initiative was conceived as a list of items for checking the report, and under no circumstances as an instrument for testing the quality of the observational study. Other tools have been put in place for this purpose36

The researcher should subsequently provide the measures of association related to their primary and secondary hypotheses, accompanied by sufficient raw data so that any reader may confirm the reported measures of association4. It is preferable to report measures of association with 95% confidence intervals instead of p values for contrasting hypotheses 34.

Establishing associations

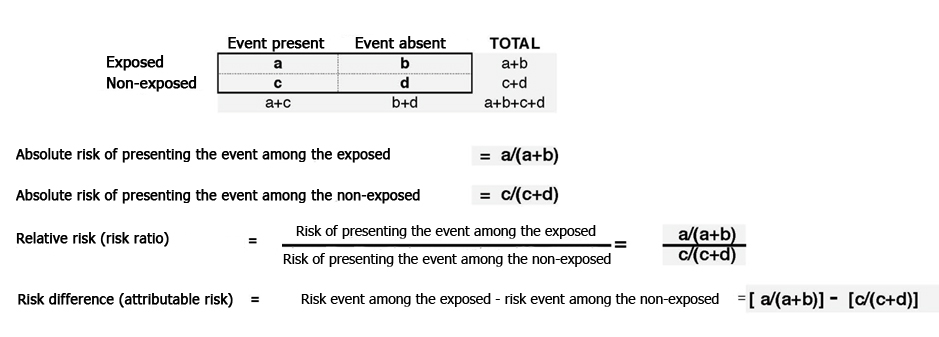

Measures of association in cohort studies can be expressed as probabilities (risks) when all individuals are followed for the same amount of time. They can also be expressed as rates when subject follow-up differs, by using a measure of people/time in the denominator. The manner in which these measures are calculated is shown in Figure 1. Thus, and as with clinical trials, it is desirable for cohort studies to ensure sufficient statistical power to detect the expected associations.

Figure 1. Main risk estimators in longitudinal studies.

Summary

Cohort studies are observational designs that have contributed enormously to biomedical knowledge. They have inherent limitations, and hence readers should ensure that sufficient control measures, such as confusion bias, are provided by the researchers.

There are standard guidelines put in place to help assess both the quality of the report as well as of the research itself

Table 1. Comparative table. Advantages/disadvantages of a cohort study design.

Table 1. Comparative table. Advantages/disadvantages of a cohort study design.

Figure 1. Main risk estimators in longitudinal studies.

Figure 1. Main risk estimators in longitudinal studies.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Authors:

Eva Madrid Aris[1], Felipe Martínez Lomakin[1,2]

Authors:

Eva Madrid Aris[1], Felipe Martínez Lomakin[1,2]

Affiliation:

[1] Centro de Investigaciones Biomédicas, Escuela de Medicina, Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile

[2] M.Sc. Programme in Evidence-Based Healthcare, University of Oxford

E-mail: eva.madrid@uv.cl

Author address:

[1] Hontaneda 2664

Edificio Dr. Bruno Günther Schaffeld

Valparaíso

Citation: Madrid E, Martínez F. . Medwave 2014;14(1):e5877 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2014.01.5877

Submission date: 25/12/2013

Acceptance date: 25/12/2013

Publication date: 2/1/2014

Comments (0)

We are pleased to have your comment on one of our articles. Your comment will be published as soon as it is posted. However, Medwave reserves the right to remove it later if the editors consider your comment to be: offensive in some sense, irrelevant, trivial, contains grammatical mistakes, contains political harangues, appears to be advertising, contains data from a particular person or suggests the need for changes in practice in terms of diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic interventions, if that evidence has not previously been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No comments on this article.

To comment please log in

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics.

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics. There may be a 48-hour delay for most recent metrics to be posted.

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. An overview of clinical research: the lay of the land. Lancet. 2002 Jan 5;359(9300):57-61. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Cohort studies: marching towards outcomes. Lancet. 2002 Jan 26;359(9303):341-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Cummings SR, Newman TB, Hulley SB. Designing a cohort study. En: Designing clinical research. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005:97-106.

- Dos Santos Silva I. Cancer Epidemiology: Principles and Methods. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1999.

- César CJ. La Guerra de las Galias: Alianza Editorial, 2002.

- Carlson MD, Morrison RS. Study design, precision, and validity in observational studies. J Palliat Med. 2009 Jan;12(1):77-82. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

- Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lin CC, Chien CS. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus. Lancet. 1981 Nov;2(8256):1129-33. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- D'Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008 Feb 12;117(6):743-53. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Beral V, Hermon C, Kay C, Hannaford P, Darby S, Reeves G. Mortality associated with oral contraceptive use: 25 year follow up of cohort of 46 000 women from Royal College of General Practitioners' oral contraception study. BMJ. 1999 Jan 9;318(7176):96-100. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality from cancer in relation to smoking: 50 years observations on British doctors. Br J Cancer. 2005 Feb 14;92(3):426-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

- Eriksson JG, Forsén T, Tuomilehto J, Osmond C, Barker DJ. Early growth and coronary heart disease in later life: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2001 Apr 21;322(7292):949-53. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

- Barker DJ, Forsén T, Uutela A, Osmond C, Eriksson JG. Size at birth and resilience to effects of poor living conditions in adult life: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2001 Dec 1;323(7324):1273-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

- Rubin DB. The design versus the analysis of observational studies for causal effects: parallels with the design of randomized trials. StatMed. 2007 Jan 15;26(1):20-36. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Kim KS, Owen WL, Williams D, Adams-Campbell LL. A comparison between BMI and Conicity index on predicting coronary heart disease: the Framingham heart study. Ann Epidemiol. 2000 Oct;10(7):424-31. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Kannel WB, McGee D, Gordon T. A general cardiovascular risk profile: the Framingham Study. Am J Cardiol. 1976 Jul;38(1):46-51. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Truett J, Cornfield J, Kannel W. A multivariate analysis of the risk of coronary heart disease in Framingham. J Chronic Dis. 1967 Jul;20(7):511-24. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Parikh NI, Pencina MJ, Wang TJ, Benjamin EJ, Lanier KJ, Levy D, et al. A risk score for predicting near-term incidence of hypertension: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann InternMed. 2008 Jan 15;148(2):102-10. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Wolf PA, Kannel WB, Sorlie P, McNamara P. Asymptomatic carotid bruit and risk of stroke. The Framingham study.JAMA. 1981 Apr 10;245(14):1442-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991 Aug;22(8):983-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Stokes J 3rd, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Cupples LA. Blood pressure as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The Framingham Study--30 years of follow-up. Hypertension. 1989 May;13(5 Suppl):I13-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Kannel WB. CHD risk factors: a Framingham study update. HospPract (Off Ed). 1990 Jul 15;25(7):119-27, 130. | PubMed |

- Kannel WB, Castelli WP, McNamara PM. Cigarette smoking and risk of coronary heart disease. Epidemiologic clues to pathogensis. The Framingham Study. Natl Cancer InstMonogr. 1968 Jun;28:9-20. | PubMed |

- Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Bonita R, Belanger AJ. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for stroke. The Framingham study. JAMA. 1988 Feb 19;259(7):1025-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors: the Framingham study. Circulation. 1979 Jan;59(1):8-13. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Franklin SS, Larson MG, Khan SA, Wong ND, Leip EP, Kannel WB, et al. Does the relation of blood pressure to coronary heart disease risk change with aging? The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2001 Mar 6;103(9):1245-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Belanger AJ, Sytkowski PA. Trends in CHD and risk factors at age 55-64 in the Framingham Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(3 Suppl 1):S67-72. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Doll R, Peto R, Hall E, Wheatley K, Gray R. Alcohol and coronary heart disease reduction among British doctors: confounding or causality? Eur Heart J. 1997 Jan;18(1):23-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Doll R, Peto R. Cigarette smoking and bronchial carcinoma: dose and time relationships among regular smokers and lifelong non-smokers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978 Dec;32(4):303-13. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

- Doll R, Peto R. Mortality among doctors in different occupations. Br Med J. 1977 Jun 4;1(6074):1433-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to alcohol consumption: a prospective study among male British doctors. Int J Epidemiol. 2005 Feb;34(1):199-204. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004 Jun 26;328(7455):1519. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

- Schauffler HH, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB. Risk for cardiovascular disease in the elderly and associated Medicare costs: the Framingham Study. Am J Prev Med. 1993 May-Jun;9(3):146-54. | PubMed |

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Smoking and dementia in male British doctors: prospective study.BMJ. 2000 Apr;320(7242):1097-102. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

- Sackett DL, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Down withodds ratios! Evidence-based Medicine. Sep-Oct 1996;6(1):164-66. | Link |

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007 Oct 20;370(9596):1453-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Jun;36(3):666-76. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Grimes DA, Schulz KF. An overview of clinical research: the lay of the land. Lancet. 2002 Jan 5;359(9300):57-61. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Grimes DA, Schulz KF. An overview of clinical research: the lay of the land. Lancet. 2002 Jan 5;359(9300):57-61. | CrossRef | PubMed | Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Cohort studies: marching towards outcomes. Lancet. 2002 Jan 26;359(9303):341-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Cohort studies: marching towards outcomes. Lancet. 2002 Jan 26;359(9303):341-5. | CrossRef | PubMed | Cummings SR, Newman TB, Hulley SB. Designing a cohort study. En: Designing clinical research. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005:97-106.

Cummings SR, Newman TB, Hulley SB. Designing a cohort study. En: Designing clinical research. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005:97-106.  Dos Santos Silva I. Cancer Epidemiology: Principles and Methods. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1999.

Dos Santos Silva I. Cancer Epidemiology: Principles and Methods. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1999.  César CJ. La Guerra de las Galias: Alianza Editorial, 2002.

César CJ. La Guerra de las Galias: Alianza Editorial, 2002.  Carlson MD, Morrison RS. Study design, precision, and validity in observational studies. J Palliat Med. 2009 Jan;12(1):77-82. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Carlson MD, Morrison RS. Study design, precision, and validity in observational studies. J Palliat Med. 2009 Jan;12(1):77-82. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lin CC, Chien CS. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus. Lancet. 1981 Nov;2(8256):1129-33. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lin CC, Chien CS. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus. Lancet. 1981 Nov;2(8256):1129-33. | CrossRef | PubMed | D'Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008 Feb 12;117(6):743-53. | CrossRef | PubMed |

D'Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008 Feb 12;117(6):743-53. | CrossRef | PubMed | Beral V, Hermon C, Kay C, Hannaford P, Darby S, Reeves G. Mortality associated with oral contraceptive use: 25 year follow up of cohort of 46 000 women from Royal College of General Practitioners' oral contraception study. BMJ. 1999 Jan 9;318(7176):96-100. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Beral V, Hermon C, Kay C, Hannaford P, Darby S, Reeves G. Mortality associated with oral contraceptive use: 25 year follow up of cohort of 46 000 women from Royal College of General Practitioners' oral contraception study. BMJ. 1999 Jan 9;318(7176):96-100. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality from cancer in relation to smoking: 50 years observations on British doctors. Br J Cancer. 2005 Feb 14;92(3):426-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality from cancer in relation to smoking: 50 years observations on British doctors. Br J Cancer. 2005 Feb 14;92(3):426-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Eriksson JG, Forsén T, Tuomilehto J, Osmond C, Barker DJ. Early growth and coronary heart disease in later life: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2001 Apr 21;322(7292):949-53. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Eriksson JG, Forsén T, Tuomilehto J, Osmond C, Barker DJ. Early growth and coronary heart disease in later life: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2001 Apr 21;322(7292):949-53. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Barker DJ, Forsén T, Uutela A, Osmond C, Eriksson JG. Size at birth and resilience to effects of poor living conditions in adult life: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2001 Dec 1;323(7324):1273-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Barker DJ, Forsén T, Uutela A, Osmond C, Eriksson JG. Size at birth and resilience to effects of poor living conditions in adult life: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2001 Dec 1;323(7324):1273-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Rubin DB. The design versus the analysis of observational studies for causal effects: parallels with the design of randomized trials. StatMed. 2007 Jan 15;26(1):20-36. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Rubin DB. The design versus the analysis of observational studies for causal effects: parallels with the design of randomized trials. StatMed. 2007 Jan 15;26(1):20-36. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kim KS, Owen WL, Williams D, Adams-Campbell LL. A comparison between BMI and Conicity index on predicting coronary heart disease: the Framingham heart study. Ann Epidemiol. 2000 Oct;10(7):424-31. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kim KS, Owen WL, Williams D, Adams-Campbell LL. A comparison between BMI and Conicity index on predicting coronary heart disease: the Framingham heart study. Ann Epidemiol. 2000 Oct;10(7):424-31. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kannel WB, McGee D, Gordon T. A general cardiovascular risk profile: the Framingham Study. Am J Cardiol. 1976 Jul;38(1):46-51. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kannel WB, McGee D, Gordon T. A general cardiovascular risk profile: the Framingham Study. Am J Cardiol. 1976 Jul;38(1):46-51. | CrossRef | PubMed | Truett J, Cornfield J, Kannel W. A multivariate analysis of the risk of coronary heart disease in Framingham. J Chronic Dis. 1967 Jul;20(7):511-24. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Truett J, Cornfield J, Kannel W. A multivariate analysis of the risk of coronary heart disease in Framingham. J Chronic Dis. 1967 Jul;20(7):511-24. | CrossRef | PubMed | Parikh NI, Pencina MJ, Wang TJ, Benjamin EJ, Lanier KJ, Levy D, et al. A risk score for predicting near-term incidence of hypertension: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann InternMed. 2008 Jan 15;148(2):102-10. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Parikh NI, Pencina MJ, Wang TJ, Benjamin EJ, Lanier KJ, Levy D, et al. A risk score for predicting near-term incidence of hypertension: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann InternMed. 2008 Jan 15;148(2):102-10. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wolf PA, Kannel WB, Sorlie P, McNamara P. Asymptomatic carotid bruit and risk of stroke. The Framingham study.JAMA. 1981 Apr 10;245(14):1442-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wolf PA, Kannel WB, Sorlie P, McNamara P. Asymptomatic carotid bruit and risk of stroke. The Framingham study.JAMA. 1981 Apr 10;245(14):1442-5. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991 Aug;22(8):983-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991 Aug;22(8):983-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Stokes J 3rd, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Cupples LA. Blood pressure as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The Framingham Study--30 years of follow-up. Hypertension. 1989 May;13(5 Suppl):I13-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Stokes J 3rd, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Cupples LA. Blood pressure as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The Framingham Study--30 years of follow-up. Hypertension. 1989 May;13(5 Suppl):I13-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kannel WB. CHD risk factors: a Framingham study update. HospPract (Off Ed). 1990 Jul 15;25(7):119-27, 130. | PubMed |

Kannel WB. CHD risk factors: a Framingham study update. HospPract (Off Ed). 1990 Jul 15;25(7):119-27, 130. | PubMed | Kannel WB, Castelli WP, McNamara PM. Cigarette smoking and risk of coronary heart disease. Epidemiologic clues to pathogensis. The Framingham Study. Natl Cancer InstMonogr. 1968 Jun;28:9-20. | PubMed |

Kannel WB, Castelli WP, McNamara PM. Cigarette smoking and risk of coronary heart disease. Epidemiologic clues to pathogensis. The Framingham Study. Natl Cancer InstMonogr. 1968 Jun;28:9-20. | PubMed | Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Bonita R, Belanger AJ. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for stroke. The Framingham study. JAMA. 1988 Feb 19;259(7):1025-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Bonita R, Belanger AJ. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for stroke. The Framingham study. JAMA. 1988 Feb 19;259(7):1025-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors: the Framingham study. Circulation. 1979 Jan;59(1):8-13. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors: the Framingham study. Circulation. 1979 Jan;59(1):8-13. | CrossRef | PubMed | Franklin SS, Larson MG, Khan SA, Wong ND, Leip EP, Kannel WB, et al. Does the relation of blood pressure to coronary heart disease risk change with aging? The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2001 Mar 6;103(9):1245-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Franklin SS, Larson MG, Khan SA, Wong ND, Leip EP, Kannel WB, et al. Does the relation of blood pressure to coronary heart disease risk change with aging? The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2001 Mar 6;103(9):1245-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Belanger AJ, Sytkowski PA. Trends in CHD and risk factors at age 55-64 in the Framingham Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(3 Suppl 1):S67-72. | CrossRef | PubMed |

D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Belanger AJ, Sytkowski PA. Trends in CHD and risk factors at age 55-64 in the Framingham Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(3 Suppl 1):S67-72. | CrossRef | PubMed | Doll R, Peto R, Hall E, Wheatley K, Gray R. Alcohol and coronary heart disease reduction among British doctors: confounding or causality? Eur Heart J. 1997 Jan;18(1):23-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Doll R, Peto R, Hall E, Wheatley K, Gray R. Alcohol and coronary heart disease reduction among British doctors: confounding or causality? Eur Heart J. 1997 Jan;18(1):23-5. | CrossRef | PubMed | Doll R, Peto R. Cigarette smoking and bronchial carcinoma: dose and time relationships among regular smokers and lifelong non-smokers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978 Dec;32(4):303-13. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Doll R, Peto R. Cigarette smoking and bronchial carcinoma: dose and time relationships among regular smokers and lifelong non-smokers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978 Dec;32(4):303-13. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Doll R, Peto R. Mortality among doctors in different occupations. Br Med J. 1977 Jun 4;1(6074):1433-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Doll R, Peto R. Mortality among doctors in different occupations. Br Med J. 1977 Jun 4;1(6074):1433-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to alcohol consumption: a prospective study among male British doctors. Int J Epidemiol. 2005 Feb;34(1):199-204. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to alcohol consumption: a prospective study among male British doctors. Int J Epidemiol. 2005 Feb;34(1):199-204. | CrossRef | PubMed | Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004 Jun 26;328(7455):1519. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004 Jun 26;328(7455):1519. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Schauffler HH, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB. Risk for cardiovascular disease in the elderly and associated Medicare costs: the Framingham Study. Am J Prev Med. 1993 May-Jun;9(3):146-54. | PubMed |

Schauffler HH, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB. Risk for cardiovascular disease in the elderly and associated Medicare costs: the Framingham Study. Am J Prev Med. 1993 May-Jun;9(3):146-54. | PubMed | Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Smoking and dementia in male British doctors: prospective study.BMJ. 2000 Apr;320(7242):1097-102. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC |

Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Smoking and dementia in male British doctors: prospective study.BMJ. 2000 Apr;320(7242):1097-102. | CrossRef | PubMed | PMC | Sackett DL, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Down withodds ratios! Evidence-based Medicine. Sep-Oct 1996;6(1):164-66. | Link |

Sackett DL, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Down withodds ratios! Evidence-based Medicine. Sep-Oct 1996;6(1):164-66. | Link |Systematization of initiatives in sexual and reproductive health about good practices criteria in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in primary health care in Chile

Clinical, psychological, social, and family characterization of suicidal behavior in Chilean adolescents: a multiple correspondence analysis