Key Words: body dissatisfaction, body image, gender identity, gender differences, transsexualism

Abstract

BACKGROUND

For subjects with gender dysphoria, body image is an important aspect of their condition. These people sometimes exhibit a strong desire to change their primary and secondary sexual characteristics. In addition, idealization of beauty has grown in importance and it may increase body dissatisfaction. The aim of this paper is to analyze whether body dissatisfaction in people with gender dysphoria is similar to that in clinical population or if it is more similar to that which may appear in general population. We also looked at gender differences in body dissatisfaction.

METHODS

A set of questionnaires was administered to patients with gender dysphoria: Eating Attitudes Test (EAT- 26), body dissatisfaction sub-scale of Eating disorder inventory-two (EDI-2) and IMAGEN questionnaire.

RESULTS

In the case of body dissatisfaction subscale of Eating disorder inventory-two with a cut-off 11; body dissatisfaction in our sample was close to the level presented in clinical population. However, using cut-off points 14 and 16, they exhibited a body dissatisfaction level that was similar to the general population. The same occurred for the IMAGEN questionnaire. No gender differences were found when looking at the level of dissatisfaction.

CONCLUSIONS

The data seem to indicate that people with gender dysphoria would be at an intermediate point in relation to body dissatisfaction between general population and clinical population; in both female and male transsexuals. It seems that some level of body dissatisfaction may be perceived in relation to the ideal of beauty, but this dissatisfaction is significantly lower than in clinical populations.

Introduction

Throughout history the concept of body image has evolved especially since the early twentieth century [1]. Baile proposes an integrative definition in which body image is a complex psychological construct about how the self-perception of the body / appearance creates a mental representation, composed by a perceptive body schema as well as its emotions, thoughts and associated behaviors.

Currently, body image not only means the way you perceive your body, but also the way one feels and acts on these insights thus, body image is an important part of self-concept. Given its complexity, if you do not have a healthy body image, the own body can become a major problem for many individuals. Dissatisfaction with body image refers to discomfort and dissatisfaction that a person feels with her or his body. It includes assessments of body parts or the whole body that tend to overestimate or distort the body proportions with negative connotations and an extreme obsession for with physical appearance that disrupts normal functioning [2].

Every culture throughout history has had a stereotype relating body image and cultural globalization [3]. Currently, "the body beauty" is promoted as a tool to achieve social success and is related to gender identity. When a person perceives not fitting these ideals of beauty, body dissatisfaction can develop in both, women and men [4],[5]. Men tend to be more concerned with the volume of their body (chest, arms or muscles), women tend to be more concerned about their weight (satisfaction shape / volume of the body or breast size) [3],[6]. For many years now, body ideals are associated with health problems, like eating disorders in women. In the last 10 years, and simultaneously with the appearance of muscular male body ideal, first cases of vigorexia or muscle dysmorphia were documented [7].

In addition, the thinness in women and muscles in men have been associating with social desirable characteristics for both, as having interpersonal and social success, health, among others. Therefore, we find that having a body according to the standards of beauty is not just a matter of preference, it has been gradually turning into building an identity [8].

Body image is a fundamental condition for subjects with gender dysphoria. Persons with gender dysphoria have a dissonance between their biological sex and their gender identity [9],[10] thus body dissatisfaction can appear. Since childhood, they have had feelings of anxiety for being totally different from those people of the same sex. They prefer playing games of the other sex. They start to wear clothes of the opposite sex from an early age, not for fun but as an expression of the feeling of belonging to that other sex which is not theirs. Their youth is affected by the alienation and loneliness. Eventually, they end up discovering their dissonance and realizing that they would be happier if they belonged to another sex [11].

There is no precise way to define membership to one sex or another. However, our body is our calling card and people will treat us as women if they perceive our body secondary sexual characteristics corresponding to a female biological sex, or men if they perceive these secondary sex characteristics corresponding to a male biological sex even if their identities are different [12].

In these cases, persons with gender dysphoria are in a continuous conflict between mind and body, since they are born and thus body dissatisfaction can appear. This dissatisfaction (morphologic dissatisfaction) is different from body dissatisfaction due to ideal body beauty internalization. Dissonance between body and gender identity is due to a hormonal illness, but internalization of body ideals could influence too. It is common in gender dysphoria subjects, a manifestation of a strong desire to change their primary and secondary sexual characteristics [13], even many of them have reported being very dissatisfied with their body, suggesting that the body is the main source of suffering [14].

We can find people with gender dysphoria who were born like men but their sexual identity correspond to women (female transsexuals) and female to male subjects (male transsexuals), people who were born like a woman but their identity correspond to a man. Male and female transsexuals make all efforts to ensure that their bodies suit their identities. These people have a persistent concern with hiding their primary and secondary sexual characteristics, and most of them ask for hormonal and surgical treatments to change sex. Female transsexuals tend to hide their male genitalia with pressure garments. Since adolescence, male transsexuals tend to wear male clothes, they often hide their breasts with compression garments, and try to pass off as people of the opposite sex in public [9].

In people with gender dysphoria, due to the consequences of the disease, some body dissatisfaction is expected due to their conflict with the body and gender identity. This body dissatisfaction is a priori different from the internalization of body ideals. However, there is not a tool that measures body dissatisfaction in general and specifically for people with gender dysphoria. Maybe ideals of beauty also are influencing in persons with gender dysphoria increasing their body dissatisfaction, so the purpose of this paper is to analyze body dissatisfaction associated with thinness in people with gender dysphoria, to describe if body dissatisfaction is within clinical alteration or if it is similar to the general population. In addition, we seek to know the differences in this variable between female and male transsexuals.

As hypothesis arises on the one hand, that people with gender dysphoria have body dissatisfaction similar to that of the general population. Also, as a second hypothesis we would expect to find gender differences in relation to body dissatisfaction: greater dissatisfaction in female transsexuals.

Methods

Participants

Cross-sectional study composed by 52 persons with gender dysphoria (30 male transsexuals and 22 female transsexuals). At the moment of the study they were in evaluation phase previous to surgeries. Hospital Clinic in Barcelona and La Fuente de San Luis health center in Valencia gender dysphoria units were contacted and they participated voluntarily. All questionnaires were collected from September 2012 to September 2013. All participants gave their consent to participate voluntarily.

Instruments

All questionnaires were inserted into a single document. A battery of questionnaires was administered with the following contents: sociodemographic data, Eating Attitudes Test (EAT- 26) [15], body dissatisfaction of Eating Disorders Inventory- 2 sub-scale (EDI- 2) [16] and IMAGEN [17].

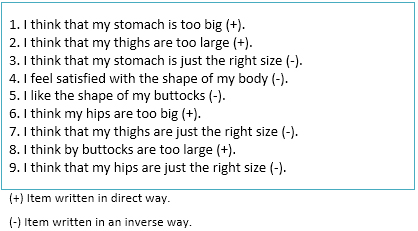

Eating Attitudes Test is a questionnaire with 26 items. It investigates diet-related disorders, bulimia, and anxiety related to food. More specifically, Eating Attitudes Test highlights the perception of one’s own weight and physical appearance. A score of 20 or above indicates that a person may have an eating disorder. The Spanish validation of the Eating Attitudes Test in our environment has been carried out by Gandarillas et al in 2013 [18]. Body dissatisfaction was measured by two questionnaires: Body dissatisfaction of EDI- 2 sub-scale and IMAGEN; last one was included due to major gender discrimination. Body dissatisfaction sub- scale is one of 11 sub- scales which are in Eating Disorders Inventory- 2 [19]. You can add up all sub-scales for a total sub-scale score or use each separately. Body dissatisfaction sub-scale has been used separately as a good indicator to value body dissatisfaction; in Table 1 we find all body dissatisfaction sub- scale items. A score of 11 (more sensible cutoff) or 14 (more specific cutoff) indicates that a person has a disadaptive body dissatisfaction [20]. Other studies consider a score of 16 as cutoff to value a possible body image disorder associated to an eating disorder [21].

Table 1. Body dissatisfaction sub-scale of Eating Disorders Inventory- 2.

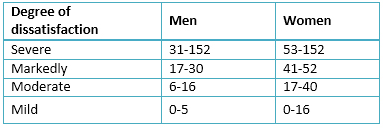

IMAGEN assesses different components of body dissatisfaction: cognitive- emotional (ICE), perceptive (IPE) and behavioural (ICL). To evaluate the frequency we used a scale with the following categories: 0 almost never/ never, 1 rarely, 2 sometimes, 3 many times, 4 almost always/ always.

In Table 2 cutoffs of the direct total score are shown.

Table 2. IMAGEN cutoffs of direct total score

To interpret in percentiles, there are two balances: for men/ woman without eating pathology risk and for men/ woman with eating pathology risk [17].

Results

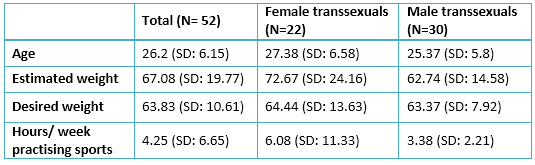

Mean age was 26.2 years old (27.38 for female transsexuals and 25.37 for male transsexuals). Mean of estimated weight of all subjects was 67.08 kg (72.6 kg for female transsexuals and 62.7 kg for male). Mean of weight was 63.83 kg for all subjects (64.44kg for female transsexuals and 63.37 kg for male). In Table 3 descriptive statistics are shown for socio demographic data.

Table 3. Mean and standard deviation (SD) for socio demographic data.

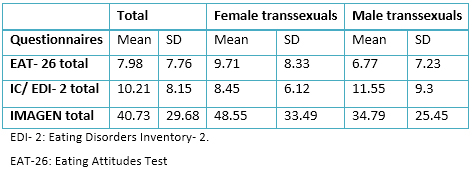

Table 4 depicts descriptive statistics for each questionnaire.

Table 4. Means and standard deviation (SD) for results, all questionnaires.

Using clinical and general population IMAGE profiles, a score of 48.55 is obtained, female transsexuals are in the 90th percentile of the general population, indicating a severe body dissatisfaction, and in the 40th of the clinical population. Thus, for this population, body dissatisfaction would be mild-moderate. In the case of male transsexuals with an average score of 34.79 they are in the 55th percentile in clinical population (moderate dissatisfaction) and the 98th percentile in the general population (severe body dissatisfaction).

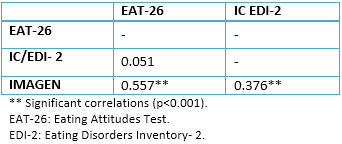

The fact of having two questionnaires to measure body dissatisfaction, in addition to the Eating Attitudes Test, allowed us to evaluate how these concepts were measured with questionnaires. The correlation coefficients between the three questionnaires are shown in Table 5. The questionnaires that measure body dissatisfaction, though they do not measure identical aspects, correlated significantly.

Table 5. Correlation coefficients between questionnaires

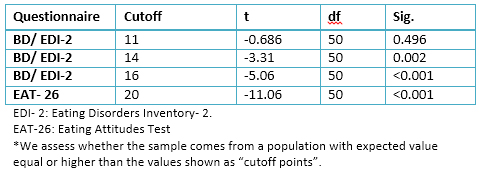

To assess whether it could be inferred that the sample came from populations with expected value greater or equal to the given cutoff points for body dissatisfaction scale of Eating Disorders Inventory-2, the Student t test for one sample was used (see Table 6). For the expected value of 11 we obtained t (50) = - 0.686, p = 0.496. For a score of 14 as the cutoff point t (50) = -3.31, p = 0.002. Finally, for the expected value of 16 t (50) = -5.06, p <0.001.

Table 6. Results from Student´s t test*

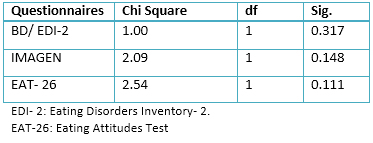

Gender differences regarding body dissatisfaction were also analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis H test. The results were c2 2 (1) = 1.00, p = 0.317; there were no differences between the types of transsexuals using body dissatisfaction subscale score of Eating Disorders Inventory- 2. Using IMAGE total score on the same test showed similar results c22 (1) = 2.09, p = 0.148. In Eating Attitudes Test a rate over 20 indicates that a person may have an eating disorder. A t test was performed to evaluate whether the sample in our study could come from a population with expected value equal or greater than 20. A t(50) = -11.06, p <0.001 was obtained. Gender difference was analyzed with Kruskal-Wallis H, and obtained a c22 (1) = 2.54, p = 0.111. All differences found in the group using the Kruskal-Wallis H are reflected in Table 7.

Table 7. Kruskal- Wallis H test results for comparing genders.

Discussion

In general, results confirm the first hypothesis. Body dissatisfaction present in people with gender dysphoria was different from that present in the clinical population, using the IMAGE and the cutoffs 14 and 16 for the subscale of body dissatisfaction EDI- 2. Only no significant differences were found when we evaluated whether the sample came from a population subscale of body dissatisfaction EDI- 2 greater than or equal to 11. Most previous studies used the cutoffs 14 and 16 as cutoff values indicating the assessment of a possible body image disorder associated with an eating disorder [20],[21].

It seems that body dissatisfaction associated with thinness in people with gender dysphoria is intermediate compared to the general population and clinical population. Perhaps pressure towards beauty ideals increases for people with gender dysphoria since at all costs intend to be identified according to their identity and not to their secondary sexual characteristics.

To interpret the results of our sample in IMAGEN questionnaire we use both profiles: clinical and general population profile. Placing the sample scores in the clinical profile, body dissatisfaction of the people with gender dysphoria is mild-moderate. However, if we move to the profile of the general population, the body dissatisfaction of the people with gender dysphoria would be severe. These data are similar to those found by Vöcks, Stahn and Loenser (2009), in which people with gender dysphoria had higher levels of dissatisfaction than the control group, but lower than people with eating disorders [22].

In fact, the hypothesis that the sample comes from populations with higher expected value in the Eating Attitudes Test is rejected. Eating attitudes are different between subjects with gender dysphoria and people with risk to suffer an eating disorder. There were no gender differences in the sample for this test.

In relation to gender difference, our second study hypothesis is rejected: no gender differences in people with gender dysphoria on the level of body dissatisfaction were found. These results were accomplished by measuring body dissatisfaction with body dissatisfaction subscale of Eating Disorders Inventory- 2 and with IMAGE. However, there are studies that found gender differences in eating pathology and issues related to body dissatisfaction [22],[23].

These data allow us to speculate that maybe people with gender dysphoria have a greater risk of suffering any problems related to body image or eating pathology [23].

Conclusions

As a general conclusion, the level of body dissatisfaction associated with thinness is above the general population in people with gender dysphoria. Body image is an important aspect of their condition, it is important to address the study of their body dissatisfaction caused by the internalization of beauty ideals. This is to avoid the development of additional problems, such as eating disorders or related to body image.

Notes

From the editor

This article was originally submitted in Spanish and was translated into English by the authors. The Journal has not copyedited this version.

Ethical issues

The Journal certifies that this study has been approved by the research ethics committee of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Spain.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors have completed the conflict of interests declaration form from the ICMJE, which has been translated into Spanish by Medwave, and they declare that they have not received any funding whatsoever to write this article, nor have they any conflict of interests with the matter dealt herein. Forms can be requested to the responsible author or the editorial direction of the Journal.

Table 1. Body dissatisfaction sub-scale of Eating Disorders Inventory- 2.

Table 1. Body dissatisfaction sub-scale of Eating Disorders Inventory- 2.

Table 2. IMAGEN cutoffs of direct total score

Table 2. IMAGEN cutoffs of direct total score

Table 3. Mean and standard deviation (SD) for socio demographic data.

Table 3. Mean and standard deviation (SD) for socio demographic data.

Table 4. Means and standard deviation (SD) for results, all questionnaires.

Table 4. Means and standard deviation (SD) for results, all questionnaires.

Table 5. Correlation coefficients between questionnaires

Table 5. Correlation coefficients between questionnaires

Table 6. Results from Student´s t test*

Table 6. Results from Student´s t test*

Table 7. Kruskal- Wallis H test results for comparing genders.

Table 7. Kruskal- Wallis H test results for comparing genders.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

INTRODUCCIÓN

Para las personas con disforia de género, la imagen corporal es un aspecto fundamental en su condición. Estas personas a veces manifiestan un fuerte deseo de cambiar sus caracteres sexuales primarios y secundarios. Además, socialmente el ideal de belleza ha ido cobrando cada vez más importancia pudiendo incrementar la insatisfacción corporal. El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar si la insatisfacción corporal en personas con disforia de género es similar a la que presenta la población clínica o si está más cerca de la que pudiera presentar la población general, así como la diferencia por géneros.

MÉTODOS

Se administraron a personas con disforia de género una batería de cuestionarios en los que se incluyeron el Test de Actitudes hacia la Alimentación, la subescala de insatisfacción corporal del Inventario para los Trastornos de Alimentación y el cuestionario IMAGEN.

RESULTADOS

En el caso de la subescala de insatisfacción corporal del Inventario para los Trastornos de Alimentación, con un punto de corte 11 la insatisfacción corporal de nuestra muestra estaría cercana al nivel de la población clínica. Sin embargo, usando los puntos de corte 14 y 16 si presentarían una insatisfacción corporal cercana a la población general, lo mismo para el IMAGEN. No se encontraron diferencias por géneros respecto al nivel de insatisfacción.

CONCLUSIONES

Los datos parecen apuntar a que las personas con disforia de género estarían en un punto intermedio en lo que se refiere a insatisfacción corporal entre la población general y la población clínica, tanto transexuales femeninas como masculinos. Parece ser que hay cierta insatisfacción corporal que pueden percibir en relación al ideal de belleza pero esta insatisfacción es bastante menor que la que pueden tener poblaciones clínicas.

Authors:

María Frenzi Rabito Alcón[1], José Miguel Rodríguez Molina[1,2]

Authors:

María Frenzi Rabito Alcón[1], José Miguel Rodríguez Molina[1,2]

Affiliation:

[1] Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, España

[2] Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, España

E-mail: mfrenzirabito@gmail.com

Author address:

[1] Facultad de Psicología de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

Despacho 11. C/

Ivan Pavlov, 6

CP: 28049

Madrid

España

Citation: Rabito Alcón MF, Rodríguez Molina . Body image in persons with gender dysphoria . Medwave 2015 May;15(4):e6138 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2015.04.6138

Submission date: 22/12/2014

Acceptance date: 5/5/2015

Publication date: 15/5/2015

Type of review: reviewed by two external peer reviewers, double-blind

Comments (0)

We are pleased to have your comment on one of our articles. Your comment will be published as soon as it is posted. However, Medwave reserves the right to remove it later if the editors consider your comment to be: offensive in some sense, irrelevant, trivial, contains grammatical mistakes, contains political harangues, appears to be advertising, contains data from a particular person or suggests the need for changes in practice in terms of diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic interventions, if that evidence has not previously been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No comments on this article.

To comment please log in

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics.

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics. There may be a 48-hour delay for most recent metrics to be posted.

- Baile JI. ¿Qué es la imagen corporal? Cuadernos del Marqués de San Adrián: revista de humanidades. 2003;(2):53-70. | Link |

- Baile JI, Raich R, Garrido E. Evaluación de insatisfacción corporal en adolescentes: efecto de la forma de autoadministración de una escala. An Psicol. 2003;19(2):187-192. | Link |

- Sepúlveda AR, Calado M. Westernization: the role of mass media on body image and eating disorders. En: Relevant topics in eating disorders. InTech, 2012 [on line]. | Link |

- Bucchianeri MM, Serrano JL, Pastula A, Corning AF. Drive for muscularity is heightened in body-dissatisfied men who socially compare. Eat Disord. 2014;22(3):221-32. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Guðnadóttir U, Garðarsdóttir RB. The influence of materialism and ideal body internalization on body-dissatisfaction and body-shaping behaviors of young men and women: support for the Consumer Culture Impact Model. Scand J Psychol. 2014 Apr;55(2):151-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Cho A, Lee JH. Body dissatisfaction levels and gender differences in attentional biases toward idealized bodies. Body Image. 2013 Jan;10(1):95-102. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Rodríguez JM, Rabito MF. Vigorexia: de la adicción al ejercicio a entidad nosológica independiente. Salud y drogas. 2011;11(1): 95-114. | Link |

- Kamps CL, Berman SL. Body image and identity formation: the role of the identity distress. Rev Latinoamericana de Psicol. 2011; 43(2):267- 277. | Link |

- Gómez E, Esteva de Antonio I, Bergero T. La transexualidad, transexualismo o trastorno de identidad de género en el adulto: concepto y características básicas. C Med Psicosom. 2006;(78):7-12. | Link |

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders Washington, DC: Author, 2013.

- Gooren L. Introducción al tema de la transexualidad. Revista de Sexología y Sociedad, 2006;12(30):4-6. | Link |

- Fernández M, García- Vega E. Variables clínicas en el trastorno de identidad de género. Psicothema. 2012;24(4): 555-560. | Link |

- Becerra A. Transexualidad. La búsqueda de una identidad. Madrid: Díaz de Santos, 2003.

- Bandini E, Fisher AD, Castellini G, Lo Sauro C, Lelli L, Meriggiola MC, et al. Gender identity disorder and eating disorders: similarities and differences in terms of body uneasiness. J Sex Med. 2013 Apr;10(4):1012-23. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med. 1982 Nov;12(4):871-8. | PubMed |

- Corral S, González M, Pereña J, Seisdedos N. Adaptación española del Inventario de trastornos de la conducta Alimentaria EDI2. Madrid: TEA, 1998.

- Solano N, Cano A. IMAGEN. Evaluación de la insatisfacción con la imagen corporal. Madrid: TEA, 2010.

- Gandarillas A, Zorrilla B, Sepúlveda AR, Muñoz P. Prevalencia de casos clínicos de trastornos del comportamiento alimentario en mujeres adolescentes de la Comunidad de Madrid. Madrid: Instituto de Salud Pública, 2003.

- Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria. Madrid: Plan de Calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud del Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2009.

- García E, Vázquez V, López JC, Arcila D. Validez interna y utilidad diagnóstica del Eating Disorders Inventory en mujeres mexicanas. Salud Pública de México. 2003;45(3):206-210. | Link |

- Baile JI, Velázquez-Castañeda A. Medición del riesgo de trastorno alimentario en una muestra de mujeres mexicanas: convergencia de tres técnicas de evaluación. Revista Mexicana de Psicología. 2006 Dic;23(2):225-233. | Link |

- Vocks S, Stahn C, Loenser K, Legenbauer T. Eating and body image disturbances in male-to-female and female-to-male transsexuals. Arch Sex Behav. 2009 Jun;38(3):364-77. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Furnham A, Badmin N, Sneade I. Body image dissatisfaction: gender differences in eating attitudes, self-esteem, and reasons for exercise. J Psychol. 2002 Nov;136(6):581-96. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Baile JI. ¿Qué es la imagen corporal? Cuadernos del Marqués de San Adrián: revista de humanidades. 2003;(2):53-70. | Link |

Baile JI. ¿Qué es la imagen corporal? Cuadernos del Marqués de San Adrián: revista de humanidades. 2003;(2):53-70. | Link | Baile JI, Raich R, Garrido E. Evaluación de insatisfacción corporal en adolescentes: efecto de la forma de autoadministración de una escala. An Psicol. 2003;19(2):187-192. | Link |

Baile JI, Raich R, Garrido E. Evaluación de insatisfacción corporal en adolescentes: efecto de la forma de autoadministración de una escala. An Psicol. 2003;19(2):187-192. | Link | Sepúlveda AR, Calado M. Westernization: the role of mass media on body image and eating disorders. En: Relevant topics in eating disorders. InTech, 2012 [on line]. | Link |

Sepúlveda AR, Calado M. Westernization: the role of mass media on body image and eating disorders. En: Relevant topics in eating disorders. InTech, 2012 [on line]. | Link | Bucchianeri MM, Serrano JL, Pastula A, Corning AF. Drive for muscularity is heightened in body-dissatisfied men who socially compare. Eat Disord. 2014;22(3):221-32. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bucchianeri MM, Serrano JL, Pastula A, Corning AF. Drive for muscularity is heightened in body-dissatisfied men who socially compare. Eat Disord. 2014;22(3):221-32. | CrossRef | PubMed | Guðnadóttir U, Garðarsdóttir RB. The influence of materialism and ideal body internalization on body-dissatisfaction and body-shaping behaviors of young men and women: support for the Consumer Culture Impact Model. Scand J Psychol. 2014 Apr;55(2):151-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Guðnadóttir U, Garðarsdóttir RB. The influence of materialism and ideal body internalization on body-dissatisfaction and body-shaping behaviors of young men and women: support for the Consumer Culture Impact Model. Scand J Psychol. 2014 Apr;55(2):151-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Cho A, Lee JH. Body dissatisfaction levels and gender differences in attentional biases toward idealized bodies. Body Image. 2013 Jan;10(1):95-102. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Cho A, Lee JH. Body dissatisfaction levels and gender differences in attentional biases toward idealized bodies. Body Image. 2013 Jan;10(1):95-102. | CrossRef | PubMed | Rodríguez JM, Rabito MF. Vigorexia: de la adicción al ejercicio a entidad nosológica independiente. Salud y drogas. 2011;11(1): 95-114. | Link |

Rodríguez JM, Rabito MF. Vigorexia: de la adicción al ejercicio a entidad nosológica independiente. Salud y drogas. 2011;11(1): 95-114. | Link | Kamps CL, Berman SL. Body image and identity formation: the role of the identity distress. Rev Latinoamericana de Psicol. 2011; 43(2):267- 277. | Link |

Kamps CL, Berman SL. Body image and identity formation: the role of the identity distress. Rev Latinoamericana de Psicol. 2011; 43(2):267- 277. | Link | Gómez E, Esteva de Antonio I, Bergero T. La transexualidad, transexualismo o trastorno de identidad de género en el adulto: concepto y características básicas. C Med Psicosom. 2006;(78):7-12. | Link |

Gómez E, Esteva de Antonio I, Bergero T. La transexualidad, transexualismo o trastorno de identidad de género en el adulto: concepto y características básicas. C Med Psicosom. 2006;(78):7-12. | Link | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders Washington, DC: Author, 2013.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders Washington, DC: Author, 2013.  Gooren L. Introducción al tema de la transexualidad. Revista de Sexología y Sociedad, 2006;12(30):4-6. | Link |

Gooren L. Introducción al tema de la transexualidad. Revista de Sexología y Sociedad, 2006;12(30):4-6. | Link | Fernández M, García- Vega E. Variables clínicas en el trastorno de identidad de género. Psicothema. 2012;24(4): 555-560. | Link |

Fernández M, García- Vega E. Variables clínicas en el trastorno de identidad de género. Psicothema. 2012;24(4): 555-560. | Link | Becerra A. Transexualidad. La búsqueda de una identidad. Madrid: Díaz de Santos, 2003.

Becerra A. Transexualidad. La búsqueda de una identidad. Madrid: Díaz de Santos, 2003.  Bandini E, Fisher AD, Castellini G, Lo Sauro C, Lelli L, Meriggiola MC, et al. Gender identity disorder and eating disorders: similarities and differences in terms of body uneasiness. J Sex Med. 2013 Apr;10(4):1012-23. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bandini E, Fisher AD, Castellini G, Lo Sauro C, Lelli L, Meriggiola MC, et al. Gender identity disorder and eating disorders: similarities and differences in terms of body uneasiness. J Sex Med. 2013 Apr;10(4):1012-23. | CrossRef | PubMed | Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med. 1982 Nov;12(4):871-8. | PubMed |

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med. 1982 Nov;12(4):871-8. | PubMed | Corral S, González M, Pereña J, Seisdedos N. Adaptación española del Inventario de trastornos de la conducta Alimentaria EDI2. Madrid: TEA, 1998.

Corral S, González M, Pereña J, Seisdedos N. Adaptación española del Inventario de trastornos de la conducta Alimentaria EDI2. Madrid: TEA, 1998.  Solano N, Cano A. IMAGEN. Evaluación de la insatisfacción con la imagen corporal. Madrid: TEA, 2010.

Solano N, Cano A. IMAGEN. Evaluación de la insatisfacción con la imagen corporal. Madrid: TEA, 2010.  Gandarillas A, Zorrilla B, Sepúlveda AR, Muñoz P. Prevalencia de casos clínicos de trastornos del comportamiento alimentario en mujeres adolescentes de la Comunidad de Madrid. Madrid: Instituto de Salud Pública, 2003.

Gandarillas A, Zorrilla B, Sepúlveda AR, Muñoz P. Prevalencia de casos clínicos de trastornos del comportamiento alimentario en mujeres adolescentes de la Comunidad de Madrid. Madrid: Instituto de Salud Pública, 2003.  Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria. Madrid: Plan de Calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud del Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2009.

Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria. Madrid: Plan de Calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud del Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2009.  García E, Vázquez V, López JC, Arcila D. Validez interna y utilidad diagnóstica del Eating Disorders Inventory en mujeres mexicanas. Salud Pública de México. 2003;45(3):206-210. | Link |

García E, Vázquez V, López JC, Arcila D. Validez interna y utilidad diagnóstica del Eating Disorders Inventory en mujeres mexicanas. Salud Pública de México. 2003;45(3):206-210. | Link | Baile JI, Velázquez-Castañeda A. Medición del riesgo de trastorno alimentario en una muestra de mujeres mexicanas: convergencia de tres técnicas de evaluación. Revista Mexicana de Psicología. 2006 Dic;23(2):225-233. | Link |

Baile JI, Velázquez-Castañeda A. Medición del riesgo de trastorno alimentario en una muestra de mujeres mexicanas: convergencia de tres técnicas de evaluación. Revista Mexicana de Psicología. 2006 Dic;23(2):225-233. | Link |Systematization of initiatives in sexual and reproductive health about good practices criteria in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in primary health care in Chile

Clinical, psychological, social, and family characterization of suicidal behavior in Chilean adolescents: a multiple correspondence analysis