Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Palabras clave: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, liver steatosis, advanced glycation end products, liver fibrosis, adipocytokines

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease refers to a disease spectrum that ranges from steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, which leads to fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Given the increasing prevalence of obesity worldwide, the incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease has become a world health problem. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is considered to be the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome associated with insulin resistance, central obesity, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Allegedly, insulin resistance plays a pivotal role in its pathogenesis. Here we highlight non-alcoholic fatty liver disease epidemiology and pathophysiology, its progression towards steatohepatitis with particular emphasis in liver fibrosis and participation of advanced glycation end products. The different treatments reported are described here as well. We conducted a search in PubMed with the terms steatohepatitis, steatosis advanced glycation end products, liver fibrosis and adipocytokines. Articles were selected according to their relevance.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become a common condition due to the increase in the prevalence of obesity. First, hepatic steatosis becomes non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is the most aggressive form of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [1]. The term non-alcoholic steatohepatitis was originally used to describe histopathological findings in patients with alcoholic liver disease but without significant consumption of alcohol (< 20 g/day) [2]. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is considered to be the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome. With a rapid increase in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease has become the most common form of liver disease [3] and is considered a public health problem [4]. This review underlines the importance of this pathology due to its relation with obesity. It describes the molecular aspects involved in the progression of steatosis to steatohepatitis, as well as the main therapeutic strategies

We carried out a search for items in PubMed database, including personal references. Articles indexed between 2000 and 2016 were chosen. We also selected articles from years prior to 2000 according to their relevance to the subject. Review articles, clinical trials and experimental studies using animal models were included. We used the search terms steatohepatitis, non-alcoholic liver disease, and adipocytokines, in combination with hepatic fibrosis, end products of advanced glycation, steatosis and steatohepatitis.

Prevalence

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease affects 20–30% of the world population. It is estimated that the prevalence of steatohepatitis is 15–20% higher in patients with obesity. The prevalence of steatosis is 45% in the Hispanic population, 33% in the Caucasian population, and 24% in the African-American population. In terms of gender, the incidence is 42% for men and 24% for women [5]. In the United States, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease increased from 47% to 75% from 1988 to 2008, and it was not a coincidence that in this time period, there was a reported increase in the prevalence of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, visceral obesity, resistance to insulin and hypertension [1]. With respect to the child population, a general prevalence of 7.6% has been reported, and the prevalence is 34.2% in children who are obese [6]. It is estimated that in Mexico, the prevalence can be as high as 20% [7]; however, recent data placed it fourth with a prevalence of 26.1%, behind Belize and Barbados with a prevalence of 28% and 28.2%, respectively [8]. The lowest prevalence has been reported in Nigeria at 9% and Iran at 4.1% [9].

Diagnosis

The majority of patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, and usually an abdominal ultrasound indicates hepatic steatosis. Detection of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is based on increased transaminase levels as well as the development of hepatomegaly. Biochemical markers in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease include hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia. Transaminase values increase with a ratio aspartate aminotransferase / alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT) <1. When the ratio is greater than 1, it suggests progression to cirrhosis [10]. Other methods that are not invasive include elastography imaging, which measures the thickness of the liver to infer the degree of fibrosis. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy is a quantitative method for measuring liver fat, and its use is limited in the clinic due to lack of availability and high cost; however, liver biopsy remains the "gold standard" since it distinguishes between simple steatosis and fibrosis [11].

Etiology

The etiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease can be divided into two major groups: 1) congenital, and 2) acquired by drugs or toxins. The first group includes type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, malnutrition, obesity, kwashiorkor or marasmus, hereditary intolerance to fructose, abetalipoproteinemia, homocystinuria, inflammatory bowel disease, and jejunal diverticulosis. The etiology for drugs and toxins as causes include glucocorticoids, tetracyclines, puromycin, methotrexate, L-asparaginase, estrogen and tamoxifen, among others [12].

Molecular aspects

Development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a complex process. It is not clear why some patients with non-alcoholic liver disease develop steatohepatitis while others do not. A possible explanation lies in genetic predisposition. It is estimated that 10% of patients with fatty liver disease progress to steatohepatitis, and of these patients, 8 to 26% progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [13]. The progression towards steatohepatitis is an event that occurs in two steps (known as the double-hit theory): the first step involves the deposit of fat in the liver as a result of insulin resistance, and the second step comprises the oxidative stress of fat in the liver derived from the release of cytokines, as well as hyperinsulinemia and lipoperoxidation [14]. However, it has been reported that this process could be a multifactorial event [15]. The accumulation of fat, and primarily of triglycerides, is the focal point for the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [16]. Below are described the main actors in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Insulin resistance and liver lipids

Insulin resistance is defined as a decrease in the ability to respond to insulin signals in the tissue, mainly skeletal muscle, liver, and adipose tissue. Insulin is an inhibitor of the production of endogenous glucose, which is altered by resistance to hepatic insulin [17]. Visceral fat gain is associated with hepatic insulin resistance since visceral fat is largely composed of lipids and fatty acids that are directly released into the vena porta. Studies on animal models have indicated that the liver can accumulate lipids in a few weeks, and even more so in a few days. It has been reported that there is alteration in the synthesis and secretion of very low density fatty acids, as well as an increase in the synthesis and oxidation of fatty acids, that results in the development of a fatty liver [18].

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease primarily affects patients with visceral obesity, dyslipidemia, resistance to insulin, and altered glucose, which are common factors of metabolic syndrome. Because of this, it is considered to be the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome [19]. Both disorders are characterized by an increase in the trend toward early development of the atherosclerotic process. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a marker of the pathological accumulation of ectopic fat. The accumulation of drops of lipids in the liver decreases its efficiency in the signaling of insulin and also causes the generation of oxidative stress that leads to the activation of nuclear factor-B, causing inhibition of the phosphorylation of the receiver of insulin-1 [20]. Recent evidence has suggested that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, independent of the traditional risk factors. This information implies that this disease can be directly involved in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease [21]. Considering that the potential mechanism by which non-alcoholic fatty liver disease increases cardiovascular risk is the development of inflammation in visceral adipose tissue, this is the main source of the flow of free fatty acids into the vena porta, causing the accumulation of fat in the liver [22].

Adipocytokines

Cytokines have a key role in the development of the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Adipose tissue is an anti-inflammatory metabolic organ that modulates the signals and metabolism of the brain, liver, muscle and cardiovascular system [23]. Energy homeostasis is maintained by the integration of metabolic functions, such as lipogenesis, lipolysis and the oxidation of fatty acids, which are mediated by adipose tissue [24]. White adipose tissue is related to energy balance and increases in obesity. The imbalance in the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory adipocytokines released by adipose tissue contributes to the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [25]. Cytokines that are secreted by fat cells, such as TNF-α, TGF-b, and IL-6, are involved in this disease, as well as leptin and adiponectin [26], among others.

Leptin

Leptin is a 16 kDa peptide hormone synthesized by adipocytes, and it is located in the liver and skeletal muscle [27]. Leptin signaling is regulated by cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases, phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase and protein kinase activated by adenosine monophosphate. Leptin acts in the hypothalamus to reduce the appetite [28]. Stimulation of leptin pathways promotes the oxidation of fatty acids and decreases lipogenesis. Leptin reduces the deposits of ectopic fat in the muscle and the liver, acts on the pancreas by inhibiting the secretion of insulin and glucagon, and promotes the homeostasis of glucose [29]. Although it is considered a hormone that activates anorexia, under certain conditions, it is increased as a result of resistance to its metabolic functions, as in obesity states. Hyperleptinemia is associated with inactivation of the leptin receptor. This negative regulation is observed in the hypothalamus and liver of obese rats [30]. In animal models, leptin prevents the accumulation of lipids in non-adipose tissue. In the liver, this effect is exerted by decreasing the expression of the lipogenic protein sterol response element-binding protein [31]. In patients with severe lipodystrophy, treatment with leptin reversed the severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. However, in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease associated with obesity, these hormone values are increased and the liver does not respond to the effects of leptin. This hormone is involved in the progression toward steatohepatitis since it is related to the development of insulin resistance. Hepatic leptin exerts a proinflammatory response, as well as the expression of genes involved in hepatic fibrogenesis, such as procollagen-1(a), TGF-b, connective tissue growth factor and smooth muscle actin [32],[33].

Adiponectin

Adiponectin is a 30 kDa hormone that is considered a promising candidate for the treatment of liver diseases because of its anti-inflammatory qualities and sensitivity to insulin. It decreases hepatic glucose production, increases glucose utilization in the muscle and increases fatty acid oxidation in the muscle and the liver, which together reduce the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6, interleukin-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Adiponectin receptors activate AMPK, p38 and proliferator receptor activator of peroxisome-α (PPAR-β), which in turn regulate the metabolism of fatty acids [34].

Low levels of adiponectin are associated with oxidative stress and a dysfunctional endothelium. Four groups have been identified: Acrp30, AdipoQ, apM1, and GBP28 [35]. Adiponectin has attracted attention due to its beneficial effects on obesity-related disorders. Hypoadiponectinemia is considered to be the key etiological factor associated with obesity. Adiponectin is assembled in various isoforms that include trimers, hexamers and complex oligomers. Obese individuals show a different adiponectin isoform distribution by presenting reduced complex-oligomeric content [36].

The increase in the ratio of complex oligomers to total adiponectin is correlated with an increase in insulin sensitivity during treatment with thiazolidinediones in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. An increase in the levels of the complex oligomeric isoform has been reported in patients who lost weight by calorie restriction or bariatric surgery. There is an inverse relationship between the levels of alanine transaminase and the complex oligomeric isoform, suggesting that the beneficial effects of adiponectin are mediated mainly by the complex oligomeric isoform. Low levels of this isoform are considered an important etiologic factor that links obesity with medical complications [36].

Proliferator receptor activator of peroxisomes (PPARs)

A key element in the process of lipogenesis and lipolysis in adipose and non-adipose tissue is mediated through the PPARs, which are members of the steroid/retinoid nuclear receptor superfamily. They act in two ways: transactivation and transrepression [37]. Three isoforms are known: PPAR-α, PPAR-ɤ, and PPAR-β. PPAR-α is expressed in the liver, kidney, heart, muscle and adipose tissue, while PPAR-β is found in the brain, adipose tissue and skin. PPAR-ɤ (ɤ-2 and ɤ-3) are expressed in adipose tissue. PPAR-ɤ is associated with sensitivity to insulin and with adipogenesis because it regulates the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial beta-oxidation of peroxisomes, liver, and skeletal muscle. PPAR-ɤ-2 is the central controller of adipogenesis because it favors adipocyte deposits in high-calorie consumption. Activation of PPAR-ɤ-3 promotes the secretion of anti-hyperglycemic adipocytokines as adiponectin [38].

Hepatic fibrosis

Hepatic fibrosis is the consequence of the formation of a scar in response to acute or chronic damage. During acute damage in the liver, architecture changes are transient and reversible, and there is chronic progressive replacement of the parenchyma tissue during healing. Etiological agents include viruses, abuse of alcohol, metabolic diseases, autoimmune and cholestatic. At a histological level, it is characterized by an almost ten-fold increase in the deposit of extracellular matrix proteins and an alteration in their composition [39].

The main population fibrogenic are stellate liver cells since they are an important source of the extracellular matrix. After an insult, these cells suffer from a phenomenon known as transdifferentiation, which is determined by a-actin expression, the loss of retinoids, the expression of cytokines and inflammatory growth factors (IL-1, TNF-α), mitogenics (platelet-derived growth factor), profibrogenics (TGF-b and IL-6), a reduction in the expression of adipogenic-lipogenic factors, and [40] chemotactic factor receptor expression [41].

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs)

Advanced glycation end products are a heterogeneous group of molecules produced by glycation and oxidation in vivo. Glycation is the main cause of spontaneous damage to proteins, and pathological complications associated with type-2 diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, renal failure, hepatic fibrosis, and steatohepatitis [42].

Also known as glycation, the Maillard reaction is the most described pathway of the formation of advanced glycation end products; it begins with the formation of unstable Schiff bases and a rearrangement that yields a more stable structure, forming products known as "Amadori products", which possess carbonyl groups that are condensed with amino groups to give rise to advanced glycation end products. The increase in the production of Amadori products results in irreversible damage if there are no mechanisms to control their excessive production. It has been reported that, in states of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, there are increased Amadori products that eventually contribute to the formation of advanced glycation end products [43].

Advanced glycation end products and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

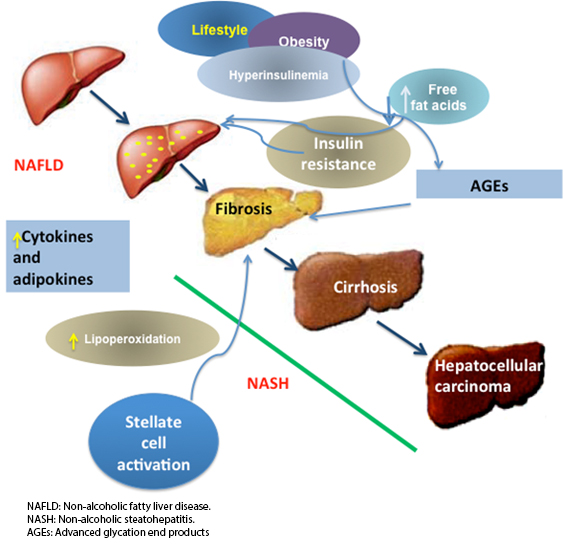

Serum levels of advanced glycation end products are normally found in low concentrations due to their constant replacement. They can be detected in vivo once sugar levels increase, as occurs in type 2 diabetes mellitus [44]. The participation of advanced glycation end products s in hepatic fibrosis is important because of the epidemic level of acquired steatohepatitis linked to obesity and metabolic syndrome, which are conditions associated with increased advanced glycation end products and their receptors. It has been documented that advanced glycation end products cause the activation and proliferation of stellate liver cells and promote the overexpression of genes involved in hepatic fibrogenesis. Advanced glycation end products derived from glyceraldehyde (glycer-AGEs) are known as toxic advanced glycation end products, whose levels are elevated in patients with steatohepatitis [45], and they activate stellate liver cells by increasing the expression of TGF-β and collagen-1(α). Knowledge about liver fibrogenesis increased with the understanding that glycer-AGEs have an important role in the progression toward steatohepatitis [46]. Figure 1 shows the evolution of different factors that lead to steatohepatitis. It presents an increase in adipocytokines and increases the flow of free fatty acids towards the liver. This leads to insulin resistance, which triggers metabolic changes that are responsible for the development of hepatic steatosis. There is an increase in lipoperoxidation, which promotes the glycation of proteins to form final advanced glycation end products, one of the factors that activate liver stellate cells, which precedes the development of liver fibrosis.

There is no medical procedure that has successfully treated non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, even though there have been many treatments reported. Study results have been controversial. Early diagnosis is the key to successful treatment. Some of the reported strategies have included a change of lifestyle, insulin sensitizers, lipid-lowering agents, antioxidants and cytoprotective agents [47].

Lifestyle interventions

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is related to overweight, an unhealthy diet and physical inactivity. Progression to steatohepatitis, in addition to being determined at the genetic level, is also influenced by different factors such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, Type 2 diabetes mellitus and aspects of an unhealthy lifestyle. From this perspective, the guide for the management of patients with steatosis is changes in lifestyle. Various reports have indicated that a 5% body weight reduction improves the activity of ALT, while a reduction of 10% decreases steatosis and necroinflammation [48].

A study that employed a 1,000 Kcal/day low-carbohydrate diet for 11 weeks in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease reported a 7.6% decrease in weight and a 38% decrease in the concentration of intrahepatic triacylglycerol. A ketogenic diet for 24 weeks showed a decrease of 1–2 levels of steatosis, as well as necroinflammation and centrilobular hepatic fibrosis; a soy protein-based diet of 800 Kcal/day resulted in a decrease of 11% and a decrease in ALT and AST of 21% and 13%, respectively [49]. Koch et al. [50] showed that intervention with a Mediterranean diet for 6 weeks reduced fatty liver. Even though it is known that fructose is involved in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Chung et al. found no association between drinks that were high in fructose and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [51]. Recent studies have indicated that a low carbohydrate diet is appropriate for patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease since intake that is rich in carbohydrates favors [52] hepatic insulin resistance. Supplementation with vitamin E significantly decreases values of AST, ALT and alkaline phosphatase, as well as the ballooning of hepatocytes [53].

Maintaining a low weight and changes in lifestyle can be difficult, and patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease could progress to steatohepatitis. Because of this, bariatric surgery represents a good alternative in the management of obesity, and it may not only involve weight loss (range of 15.1 points in the body mass index), but may also involve the resolution of various factors, including normalization of tolerance to insulin (which can result in the resolution of type 2 diabetes mellitus) and the reduction of cardiovascular risk. Improved histological and biochemical levels have been reported as a result of surgery in patients with non-alcoholic liver disease. A meta-analysis carried out by Bower et al. suggested that the incidence of steatosis in patients undergoing bariatric surgery fell 50.2%, with a decrease of 3.8% for steatohepatitis. They also reported a decrease of 67.7% in hepatocyte ballooning and a decline in the levels of transaminases (11.63 ALT U/l and AST 3.91 U/l) [54].

Impact of physical activity on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

With respect to the intervention of lifestyle changes, and considering physical activity, several studies have indicated that there is an impact on the reduction of hepatic steatosis and a reduction in progression to cirrhosis, as well as improvement in insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular health. It has been reported that a program with a physical workload that is > 10,000 kcal is associated with a decrease in intrahepatic fat of 3.46% and significant decreases in the levels of free fatty acids [55] and transaminases [56]. However, accurate information is still lacking regarding the exact duration that is required to cause an improvement in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [57].

Metformin

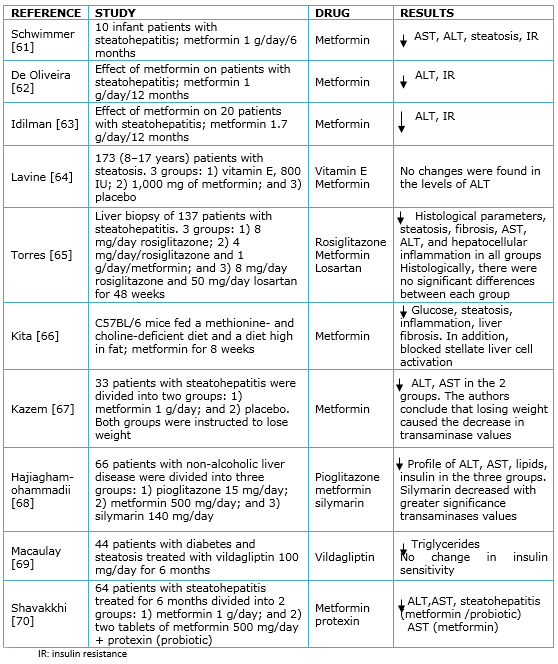

The association between insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease suggests that insulin resistance makes a white therapeutic logical. In this sense, two classes of drugs have been used: biguanides and thiazolidinediones. Metformin is a biguanide that is used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus as an insulin sensitizer, which reduces hyperinsulinemia. Its main effects include reducing the production of glucose in the liver [58]. It has been reported that it presents favorable results in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; the aminotransferases values are decreased, possibly due reductions in weight [59]. At the histological level, an improvement in the level of steatosis, necroinflammation and hepatic fibrosis has been reported. In patients with steatosis, treatment with metformin, combined with a lipid-restricted diet for six months, resulted in recovery of transaminases and insulin sensitivity [60]; however, the results with this drug for steatohepatitis and steatosis are controversial. Table 1 summarizes the related studies.

Table 1. Pharmacological agents for the treatment of non-alcoholic liver disease.

Thiazolidinediones

Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are used in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease for their action against hyperinsulinemia. Sanyal et al. [71] reported that pioglitazone decreases AST and ALT levels. On a histological level, a decrease in steatosis was observed. Treatment for 48 weeks (30 mg/day) improved biochemical and histological parameters; however, their use was significantly limited due to the increase in weight [72]. On the other hand, Aithal et al. [73] observed an increase not only in weight but also in hepatic fibrosis.

Farsenoid X receptor agonist

The farsenoid X receptor agonist is a sensor of bile that plays an important role in the regulation of bile and cholesterol homeostasis, metabolism and glucose sensitivity. Aguilar et al. reported overexpression of the farsenoid X receptor in patients with steatohepatitis, but not in patients with steatosis, suggesting that the farsenoid X receptor is involved in the progression to steatohepatitis [74].

Adiponectin

Adiponectin and its agonists represent a promising therapy for the treatment and/or prevention of hepatic dysfunction [75]. The design of drugs that increase the production of this hormone may represent a suitable treatment for the prevention of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [47].

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is an effective antioxidant. Its use is recognized as a treatment that is appropriate for patients with steatohepatitis but without diabetes. In these patients, supplementation with vitamin E decreased the levels of transaminases and steatohepatitis [76]; however, conflicting results were reported by Lavine et al. [64].

Statins

Statins are competitive inhibitors of hydroxymethyl coenzyme-A. The use of rosuvastatin (10 mg/day) normalized lipid profiles, decreased transaminase levels, and produced total resolution of steatohepatitis in 5 of 6 patients; however, the limitation of this study was the small sample size [77]. In a study of 22 patients, treatment with atorvastatin (80 mg/day) for 6 months decreased the levels of transaminases, as well as the lipid profile [78].

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is the most common liver disorder, and it has become a growing problem around the world. It is considered the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome. The high incidence and prevalence of obesity is already considered a pandemic and therefore a public health problem. This situation is alarming in our country and will continue to be so in the coming years considering that, at present, Mexico is first place in childhood obesity and the second place in adult obesity.

Despite advances in understanding and treating non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, there are still points to be resolved, such as the development of early markers for the disease. Additionally, molecular, biochemical and genetic research is urgently needed to allow the development of appropriate therapeutic strategies. As has been observed, the treatment for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is controversial and, from our point of view, intervention and lifestyle changes are essential for dealing with obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus 2.

From the editor

The authors originally submitted this article in Spanish and subsequently translated it into English. The Journal has not copyedited this version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE conflict of interest declaration form, translated to Spanish by Medwave, and declare not having received funding for the preparation of this report, not having any financial relationships with organizations that could have interests in the published article in the last three years, and not having other relations or activities that might influence the article´s content. Forms can be requested to the responsible author or the editorial direction of the Journal.

Funding

The authors declare that there was no funding coming from external sources. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Figure 1. Evolution from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease to steatohepatitis begins with obesity and overweight.

Figure 1. Evolution from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease to steatohepatitis begins with obesity and overweight.

Table 1. Pharmacological agents for the treatment of non-alcoholic liver disease.

Table 1. Pharmacological agents for the treatment of non-alcoholic liver disease.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease refers to a disease spectrum that ranges from steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, which leads to fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Given the increasing prevalence of obesity worldwide, the incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease has become a world health problem. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is considered to be the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome associated with insulin resistance, central obesity, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Allegedly, insulin resistance plays a pivotal role in its pathogenesis. Here we highlight non-alcoholic fatty liver disease epidemiology and pathophysiology, its progression towards steatohepatitis with particular emphasis in liver fibrosis and participation of advanced glycation end products. The different treatments reported are described here as well. We conducted a search in PubMed with the terms steatohepatitis, steatosis advanced glycation end products, liver fibrosis and adipocytokines. Articles were selected according to their relevance.

Autores:

Elizabeth Hernández-Pérez[1,2], Plácido Enrique León García[2], Norma Edith López-Díazguerrero[1], Fernando Rivera-Cabrera[1], Elizabeth del Ángel Benítez[1]

Autores:

Elizabeth Hernández-Pérez[1,2], Plácido Enrique León García[2], Norma Edith López-Díazguerrero[1], Fernando Rivera-Cabrera[1], Elizabeth del Ángel Benítez[1]

Citación: Hernández-Pérez E, León García PE, López-Díazguerrero NE, Rivera-Cabrera F, del Ángel Benítez E. Liver steatosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: from pathogenesis to therapy. Medwave 2016 Sep;16(8):e6535 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2016.08.6535

Fecha de envío: 18/5/2016

Fecha de aceptación: 22/8/2016

Fecha de publicación: 13/9/2016

Origen: no solicitado

Tipo de revisión: con revisión por tres pares revisores externos, a doble ciego

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Angulo P, Lindor KD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002 Feb;17 Suppl:S186-90. | PubMed |

Angulo P, Lindor KD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002 Feb;17 Suppl:S186-90. | PubMed | Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980 Jul;55(7):434-8. | PubMed |

Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980 Jul;55(7):434-8. | PubMed | Krawczyk M, Bonfrate L, Portincasa P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct;24(5):695-708. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Krawczyk M, Bonfrate L, Portincasa P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct;24(5):695-708. | CrossRef | PubMed | Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Aug;34(3):274-85. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Aug;34(3):274-85. | CrossRef | PubMed | Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, et al. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004 Dec;40(6):1387-95. | PubMed |

Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, et al. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004 Dec;40(6):1387-95. | PubMed | Anderson E, Howe L, Jones H, Higgins J, Lawlor D, Frasse A. the prevalence of non-alcoholic. fatty liver disease in children and adolescent: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Plos one. 2015 oct;10(10) | CrossRef |

Anderson E, Howe L, Jones H, Higgins J, Lawlor D, Frasse A. the prevalence of non-alcoholic. fatty liver disease in children and adolescent: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Plos one. 2015 oct;10(10) | CrossRef | Wolpert E, Kershenobich D. Esteatosis y esteatohepatitis no alcoholica. facmed.unam.mx [on line]. | Link |

Wolpert E, Kershenobich D. Esteatosis y esteatohepatitis no alcoholica. facmed.unam.mx [on line]. | Link | López-Velázquez JA, Silva-Vidal KV, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Chávez-Tapia NC, Arrese M, Uribe M, et al. The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the Americas. Ann Hepatol. 2014 Mar-Apr;13(2):166-78. | PubMed |

López-Velázquez JA, Silva-Vidal KV, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Chávez-Tapia NC, Arrese M, Uribe M, et al. The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the Americas. Ann Hepatol. 2014 Mar-Apr;13(2):166-78. | PubMed | Sherif ZA, Saeed A, Ghavimi S, Nouraie SM, Laiyemo AO, Brim H, et al. Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Perspectives on US Minority Populations. Dig Dis Sci. 2016 May;61(5):1214-25. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sherif ZA, Saeed A, Ghavimi S, Nouraie SM, Laiyemo AO, Brim H, et al. Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Perspectives on US Minority Populations. Dig Dis Sci. 2016 May;61(5):1214-25. | CrossRef | PubMed | Basaranoglu M,Ormeci N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease diagnosis, pathogenesis and management. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014 Apr;25:127-32. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Basaranoglu M,Ormeci N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease diagnosis, pathogenesis and management. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014 Apr;25:127-32. | CrossRef | PubMed | Szczepaniak LS, Nurenberg P, Leonard D, Browning JD, Reingold JS, Grundy S, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure hepatic triglyceride content: prevalence of hepatic steatosis in the general population. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Feb;28 (2):E462-8. | PubMed |

Szczepaniak LS, Nurenberg P, Leonard D, Browning JD, Reingold JS, Grundy S, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure hepatic triglyceride content: prevalence of hepatic steatosis in the general population. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Feb;28 (2):E462-8. | PubMed | Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, Cerrelli F, Lenzi M, Manini R, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology. 2003 Apr;37(4):917-23. | PubMed |

Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, Cerrelli F, Lenzi M, Manini R, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology. 2003 Apr;37(4):917-23. | PubMed | Yatsuji S, Hashimoto E, Tobari M, Taniai M, Tokushige K, Shiratori K. Clinical features and outcomes of cirrhosis due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis compared with cirrhosis caused by chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Feb;24(2):248-54. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Yatsuji S, Hashimoto E, Tobari M, Taniai M, Tokushige K, Shiratori K. Clinical features and outcomes of cirrhosis due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis compared with cirrhosis caused by chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Feb;24(2):248-54. | CrossRef | PubMed | Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two "hits"? Gastroenterology. 1998 Apr;114(4):842-5. | PubMed |

Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two "hits"? Gastroenterology. 1998 Apr;114(4):842-5. | PubMed | Tilg H, Moschen AR. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology. 2010 Nov;52(5):1836-46. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tilg H, Moschen AR. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology. 2010 Nov;52(5):1836-46. | CrossRef | PubMed | Marra F, Gastaldelli A, Svegliati Baroni G, Tell G, Tiribelli C. Molecular basis and mechanisms of progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Trends Mol Med. 2008 Feb;14(2):72-81. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Marra F, Gastaldelli A, Svegliati Baroni G, Tell G, Tiribelli C. Molecular basis and mechanisms of progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Trends Mol Med. 2008 Feb;14(2):72-81. | CrossRef | PubMed | Utzschneider KM, Kahn SE. Review: The role of insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Dec;91(12):4753-61. | PubMed |

Utzschneider KM, Kahn SE. Review: The role of insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Dec;91(12):4753-61. | PubMed | Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Qu X, Elder BD, Bilz S, Befroy D, et al. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2004 Jul 30;279(31):32345-53. | PubMed |

Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Qu X, Elder BD, Bilz S, Befroy D, et al. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2004 Jul 30;279(31):32345-53. | PubMed | Gaudio E, Nobili V, Franchitto A, Onori P, Carpino G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and atherosclerosis. Intern Emerg Med. 2012 Oct;7 Suppl 3:S297-305. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gaudio E, Nobili V, Franchitto A, Onori P, Carpino G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and atherosclerosis. Intern Emerg Med. 2012 Oct;7 Suppl 3:S297-305. | CrossRef | PubMed | Byrne CD, Targher G. Ectopic fat, insulin resistance, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: implications for cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014 Jun;34(6):1155-61. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Byrne CD, Targher G. Ectopic fat, insulin resistance, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: implications for cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014 Jun;34(6):1155-61. | CrossRef | PubMed | Yoo HJ, Choi KM. Hepatokines as a Link between Obesity and Cardiovascular Diseases. Diabetes Metab J. 2015 Feb;39(1):10-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Yoo HJ, Choi KM. Hepatokines as a Link between Obesity and Cardiovascular Diseases. Diabetes Metab J. 2015 Feb;39(1):10-5. | CrossRef | PubMed | Björntorp P. "Portal" adipose tissue as a generator of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Arteriosclerosis. 1990 Jul-Aug;10(4):493-6.

| PubMed |

Björntorp P. "Portal" adipose tissue as a generator of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Arteriosclerosis. 1990 Jul-Aug;10(4):493-6.

| PubMed | Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, Lehrke M, Hendler RE, Shulman GI. Reversal of nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis, hepatic insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia by moderate weight reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005 Mar;54(3):603-8. | PubMed |

Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, Lehrke M, Hendler RE, Shulman GI. Reversal of nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis, hepatic insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia by moderate weight reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005 Mar;54(3):603-8. | PubMed | Matsuzawa Y. Adiponectin: a key player in obesity related disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2010 Jun;16(17):1896-901. | PubMed |

Matsuzawa Y. Adiponectin: a key player in obesity related disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2010 Jun;16(17):1896-901. | PubMed | Mirza MS. Obesity, Visceral Fat, and NAFLD: Querying the Role of Adipokines in the Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2011;2011:592404. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Mirza MS. Obesity, Visceral Fat, and NAFLD: Querying the Role of Adipokines in the Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2011;2011:592404. | CrossRef | PubMed | Tarantino G, Savastano S, Colao A. Hepatic steatosis, low-grade chronic inflammation and hormone/growth factor/adipokine imbalance. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct 14;16(38):4773-83. | PubMed |

Tarantino G, Savastano S, Colao A. Hepatic steatosis, low-grade chronic inflammation and hormone/growth factor/adipokine imbalance. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct 14;16(38):4773-83. | PubMed | Giby VG, Ajith TA. Role of adipokines and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2014 Aug 27;6(8):570-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Giby VG, Ajith TA. Role of adipokines and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2014 Aug 27;6(8):570-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wauman J, Tavernier J. Leptin receptor signaling: pathways to leptin resistance. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2011 Jun 1;16:2771-93. | PubMed |

Wauman J, Tavernier J. Leptin receptor signaling: pathways to leptin resistance. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2011 Jun 1;16:2771-93. | PubMed | Denver RJ, Bonett RM, Boorse GC. Evolution of leptin structure and function. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;94(1):21-38. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Denver RJ, Bonett RM, Boorse GC. Evolution of leptin structure and function. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;94(1):21-38. | CrossRef | PubMed | Marroquí L, Vieira E, Gonzalez A, Nadal A, Quesada I. Leptin downregulates expression of the gene encoding glucagon in alphaTC1-9 cells and mouse islets. Diabetologia. 2011 Apr;54(4):843-51. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Marroquí L, Vieira E, Gonzalez A, Nadal A, Quesada I. Leptin downregulates expression of the gene encoding glucagon in alphaTC1-9 cells and mouse islets. Diabetologia. 2011 Apr;54(4):843-51. | CrossRef | PubMed | Fuentes T, Ara I, Guadalupe-Grau A, Larsen S, Stallknecht B, Olmedillas H, et al. Leptin receptor 170 kDa (OB-R170) protein expression is reduced in obese human skeletal muscle: a potential mechanism of leptin resistance. Exp Physiol. 2010 Jan;95(1):160-71. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Fuentes T, Ara I, Guadalupe-Grau A, Larsen S, Stallknecht B, Olmedillas H, et al. Leptin receptor 170 kDa (OB-R170) protein expression is reduced in obese human skeletal muscle: a potential mechanism of leptin resistance. Exp Physiol. 2010 Jan;95(1):160-71. | CrossRef | PubMed | Fiorenza CG, Chou SH, Mantzoros CS. Lipodystrophy: pathophysiology and advances in treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011 Mar;7(3):137-50. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Fiorenza CG, Chou SH, Mantzoros CS. Lipodystrophy: pathophysiology and advances in treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011 Mar;7(3):137-50. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kukla M, Mazur W, Bułdak RJ, Zwirska-Korczala K. Potential role of leptin, adiponectin and three novel adipokines--visfatin, chemerin and vaspin--in chronic hepatitis. Mol Med. 2011;17(11-12):1397-410. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kukla M, Mazur W, Bułdak RJ, Zwirska-Korczala K. Potential role of leptin, adiponectin and three novel adipokines--visfatin, chemerin and vaspin--in chronic hepatitis. Mol Med. 2011;17(11-12):1397-410. | CrossRef | PubMed | Tarantino G, Finelli C, Colao A, Capone D, Tarantino M, Grimaldi E, et al. Are hepatic steatosis and carotid intima media thickness associated in obese patients with normal or slightly elevated gamma-glutamyl-transferase? J Transl Med. 2012 Mar 16;10:50. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tarantino G, Finelli C, Colao A, Capone D, Tarantino M, Grimaldi E, et al. Are hepatic steatosis and carotid intima media thickness associated in obese patients with normal or slightly elevated gamma-glutamyl-transferase? J Transl Med. 2012 Mar 16;10:50. | CrossRef | PubMed | Yoon MJ, Lee GY, Chung JJ, Ahn YH, Hong SH, Kim JB. Adiponectin increases fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle cells by sequential activation of AMP-activated protein kinase, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Diabetes. 2006 Sep;55(9):2562-70. | PubMed |

Yoon MJ, Lee GY, Chung JJ, Ahn YH, Hong SH, Kim JB. Adiponectin increases fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle cells by sequential activation of AMP-activated protein kinase, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Diabetes. 2006 Sep;55(9):2562-70. | PubMed | Bracale R, Labruna G, Finelli C, Daniele A, Sacchetti L, Oriani G, et al. The absence of polymorphisms in ADRB3, UCP1, PPARγ, and ADIPOQ genes protects morbid obese patients toward insulin resistance. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012 Jan;35(1):2-4. | PubMed |

Bracale R, Labruna G, Finelli C, Daniele A, Sacchetti L, Oriani G, et al. The absence of polymorphisms in ADRB3, UCP1, PPARγ, and ADIPOQ genes protects morbid obese patients toward insulin resistance. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012 Jan;35(1):2-4. | PubMed | Simpson F, Whitehead JP. Adiponectin--it's all about the modifications. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010 Jun;42(6):785-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Simpson F, Whitehead JP. Adiponectin--it's all about the modifications. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010 Jun;42(6):785-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gervois P, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Drug Insight: mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications for agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Feb;3(2):145-56. | PubMed |

Gervois P, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Drug Insight: mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications for agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Feb;3(2):145-56. | PubMed | Gressner OA, Gao C. Monitoring fibrogenic progression in the liver. Clin Chim Acta. 2014 Jun 10;433:111-22. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gressner OA, Gao C. Monitoring fibrogenic progression in the liver. Clin Chim Acta. 2014 Jun 10;433:111-22. | CrossRef | PubMed | Hernández E, Bucio L, Souza V, Escobar MC, Gómez-Quiroz LE, Farfán B, et al. Pentoxifylline downregulates alpha (I) collagen expression by the inhibition of Ikappabalpha degradation in liver stellate cells. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2008 Aug;24(4):303-14. | PubMed |

Hernández E, Bucio L, Souza V, Escobar MC, Gómez-Quiroz LE, Farfán B, et al. Pentoxifylline downregulates alpha (I) collagen expression by the inhibition of Ikappabalpha degradation in liver stellate cells. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2008 Aug;24(4):303-14. | PubMed | Gaens KH, Niessen PM, Rensen SS, Buurman WA, Greve JW, Driessen A, et al. Endogenous formation of Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine is increased in fatty livers and induces inflammatory markers in an in vitro model of hepatic steatosis. J Hepatol. 2012 Mar;56(3):647-55. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gaens KH, Niessen PM, Rensen SS, Buurman WA, Greve JW, Driessen A, et al. Endogenous formation of Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine is increased in fatty livers and induces inflammatory markers in an in vitro model of hepatic steatosis. J Hepatol. 2012 Mar;56(3):647-55. | CrossRef | PubMed | Piarulli F, Sartore G, Lapolla A. Glyco-oxidation and cardiovascular complications in type 2 diabetes: a clinical update. Acta Diabetol. 2013 Apr;50(2):101-10. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Piarulli F, Sartore G, Lapolla A. Glyco-oxidation and cardiovascular complications in type 2 diabetes: a clinical update. Acta Diabetol. 2013 Apr;50(2):101-10. | CrossRef | PubMed | Lohwasser C, Neureiter D, Popov Y, Bauer M, Schuppan D. Role of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in hepatic fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Dec 14;15(46):5789-98.

| PubMed |

Lohwasser C, Neureiter D, Popov Y, Bauer M, Schuppan D. Role of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in hepatic fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Dec 14;15(46):5789-98.

| PubMed | Takeuchi M, Takino J, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takata T, Ueda T, Tsutsumi T, et al. Involvement of the TAGE:RAGE system in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: novel treatment strategies. World J Hepatol. 2014 Dec 27;6(12):880-93. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Takeuchi M, Takino J, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takata T, Ueda T, Tsutsumi T, et al. Involvement of the TAGE:RAGE system in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: novel treatment strategies. World J Hepatol. 2014 Dec 27;6(12):880-93. | CrossRef | PubMed | Iwamoto K, Kanno K, Hyogo H, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Tazuma S, et al. Advanced glycation end products enhance the proliferation and activation of hepatic stellate cells. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(4):298-304. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Iwamoto K, Kanno K, Hyogo H, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Tazuma S, et al. Advanced glycation end products enhance the proliferation and activation of hepatic stellate cells. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(4):298-304. | CrossRef | PubMed | Finelli C, Tarantino G. What is the role of adiponectin in obesity related non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Feb 14;19(6):802-12. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Finelli C, Tarantino G. What is the role of adiponectin in obesity related non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Feb 14;19(6):802-12. | CrossRef | PubMed | Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, Jackvony E, Kearns M, Wands JR, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010 Jan;51(1):121-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, Jackvony E, Kearns M, Wands JR, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010 Jan;51(1):121-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Thoma C, Day CP, Trenell MI. Lifestyle interventions for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012 Jan;56(1):255-66. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Thoma C, Day CP, Trenell MI. Lifestyle interventions for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012 Jan;56(1):255-66. | CrossRef | PubMed | Koch M, Nöthlings U, Lieb W. Dietary patterns and fatty liver disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2015 Feb;26(1):35-41. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Koch M, Nöthlings U, Lieb W. Dietary patterns and fatty liver disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2015 Feb;26(1):35-41. | CrossRef | PubMed | Chung M, Ma J, Patel K, Berger S, Lau J, Lichtenstein AH. Fructose, high-fructose corn syrup, sucrose, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or indexes of liver health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr.2014 Sep;100(3):833-49. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Chung M, Ma J, Patel K, Berger S, Lau J, Lichtenstein AH. Fructose, high-fructose corn syrup, sucrose, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or indexes of liver health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr.2014 Sep;100(3):833-49. | CrossRef | PubMed | Hashemi Kani A, Alavian SM, Haghighatdoost F, Azadbakht L. Diet macronutrients composition in nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease: a review on the related documents. Hepat Mon. 2014 Feb 17;14(2):e10939. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hashemi Kani A, Alavian SM, Haghighatdoost F, Azadbakht L. Diet macronutrients composition in nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease: a review on the related documents. Hepat Mon. 2014 Feb 17;14(2):e10939. | CrossRef | PubMed | Sato K, Gosho M, Yamamoto T, Kobayashi Y, Ishii N, Ohashi T, et al. Vitamin E has a beneficial effect on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition. 2015 Jul-Aug;31(7-8):923-30. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sato K, Gosho M, Yamamoto T, Kobayashi Y, Ishii N, Ohashi T, et al. Vitamin E has a beneficial effect on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition. 2015 Jul-Aug;31(7-8):923-30. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bower G, Toma T, Harling L, Jiao LR, Efthimiou E, Darzi A, et al. Bariatric Surgery and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: a Systematic Review of Liver Biochemistry and Histology. Obes Surg. 2015 Dec;25(12):2280-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bower G, Toma T, Harling L, Jiao LR, Efthimiou E, Darzi A, et al. Bariatric Surgery and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: a Systematic Review of Liver Biochemistry and Histology. Obes Surg. 2015 Dec;25(12):2280-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Smart NA, King N, McFarlane JR, Graham PL, Dieberg G. Effect of exercise training on liver function in adults who are overweight or exhibit fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Jun 17. pii: bjsports-2016-096197. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Smart NA, King N, McFarlane JR, Graham PL, Dieberg G. Effect of exercise training on liver function in adults who are overweight or exhibit fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Jun 17. pii: bjsports-2016-096197. | CrossRef | PubMed | Orci LA, Gariani K, Oldani G, Delaune V, Morel P, Toso C. Exercise-based Interventions for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Meta-analysis and Meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 May 4. pii: S1542-3565(16)30149-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Orci LA, Gariani K, Oldani G, Delaune V, Morel P, Toso C. Exercise-based Interventions for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Meta-analysis and Meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 May 4. pii: S1542-3565(16)30149-5. | CrossRef | PubMed | Whitsett M, VanWagner L. Physical activity as a treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. World J Hepatol. 2015 Aug 8;7(16):2041-52. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Whitsett M, VanWagner L. Physical activity as a treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. World J Hepatol. 2015 Aug 8;7(16):2041-52. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers J. Metformin: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Jul;137(1):25. | PubMed |

Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers J. Metformin: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Jul;137(1):25. | PubMed | Angelico F, Burattin M, Alessandri C, Del Ben M, Lirussi F. Drugs improving insulin resistance for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and/or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD005166.

| PubMed |

Angelico F, Burattin M, Alessandri C, Del Ben M, Lirussi F. Drugs improving insulin resistance for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and/or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD005166.

| PubMed | Bugianesi E, Gentilcore E, Manini R, Natale S, Vanni E, Villanova N, et al. A randomized controlled trial of metformin versus vitamin E or prescriptive diet in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 May;100(5):1082-90. | PubMed |

Bugianesi E, Gentilcore E, Manini R, Natale S, Vanni E, Villanova N, et al. A randomized controlled trial of metformin versus vitamin E or prescriptive diet in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 May;100(5):1082-90. | PubMed | Schwimmer JB, Behling C, Newbury R, Deutsch R, Nievergelt C, Schork NJ, et al. Histopathology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005 Sep;42(3):641-9. | PubMed |

Schwimmer JB, Behling C, Newbury R, Deutsch R, Nievergelt C, Schork NJ, et al. Histopathology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005 Sep;42(3):641-9. | PubMed | de Oliveira CP, Stefano JT, de Siqueira ER, Silva LS, de Campos Mazo DF, Lima VM, et al. Combination of N-acetylcysteine and metformin improves histological steatosis and fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2008;38(2):159-65.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

de Oliveira CP, Stefano JT, de Siqueira ER, Silva LS, de Campos Mazo DF, Lima VM, et al. Combination of N-acetylcysteine and metformin improves histological steatosis and fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2008;38(2):159-65.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Idilman R, Mizrak D, Corapcioglu D, Bektas M, Doganay B, Sayki M, et al. Clinical trial: insulin-sensitizing agents may reduce consequences of insulin resistance in individuals with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Jul;28(2):200-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Idilman R, Mizrak D, Corapcioglu D, Bektas M, Doganay B, Sayki M, et al. Clinical trial: insulin-sensitizing agents may reduce consequences of insulin resistance in individuals with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Jul;28(2):200-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, Van Natta ML, Molleston JP, Murray KF, Rosenthal P. et al. Effect of vitamin E or metformin for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: the TONIC randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1659-68. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, Van Natta ML, Molleston JP, Murray KF, Rosenthal P. et al. Effect of vitamin E or metformin for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: the TONIC randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1659-68. | CrossRef | PubMed | Torres DM, Jones FJ, Shaw JC, Williams CD, Ward JA, Harrison SA. Rosiglitazone versus rosiglitazone and metformin versus rosiglitazone and losartan in the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in humans: a 12-month randomized, prospective, open- label trial. Hepatology. 2011 Nov;54(5):1631-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Torres DM, Jones FJ, Shaw JC, Williams CD, Ward JA, Harrison SA. Rosiglitazone versus rosiglitazone and metformin versus rosiglitazone and losartan in the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in humans: a 12-month randomized, prospective, open- label trial. Hepatology. 2011 Nov;54(5):1631-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kita Y, Takamura T, Misu H, Ota T, Kurita S, Takeshita Y, et al. Metformin prevents and reverses inflammation in a non-diabetic mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e43056. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kita Y, Takamura T, Misu H, Ota T, Kurita S, Takeshita Y, et al. Metformin prevents and reverses inflammation in a non-diabetic mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e43056. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kazemi R, Aduli M, Sotoudeh M, Malekzadeh R, Seddighi N, Sepanlou SG, et al. Metformin in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2012 Jan;4(1):16-22. | PubMed |

Kazemi R, Aduli M, Sotoudeh M, Malekzadeh R, Seddighi N, Sepanlou SG, et al. Metformin in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2012 Jan;4(1):16-22. | PubMed | Hajiaghamohammadi AA, Ziaee A, Oveisi S, Masroor H. Effects of metformin, pioglitazone, and silymarin treatment on non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled pilot study. Hepat Mon. 2012 Aug;12(8):e6099. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hajiaghamohammadi AA, Ziaee A, Oveisi S, Masroor H. Effects of metformin, pioglitazone, and silymarin treatment on non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled pilot study. Hepat Mon. 2012 Aug;12(8):e6099. | CrossRef | PubMed | Macauley M, Hollingsworth KG, Smith FE, Thelwall PE, Al-Mrabeh A, Schweizer A, et al. Effect of vildagliptin on hepatic steatosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Apr;100(4):1578-85. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Macauley M, Hollingsworth KG, Smith FE, Thelwall PE, Al-Mrabeh A, Schweizer A, et al. Effect of vildagliptin on hepatic steatosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Apr;100(4):1578-85. | CrossRef | PubMed | Shavakhi A, Minakari M, Firouzian H, Assali R, Hekmatdoost A, Ferns G. Effect of a Probiotic and Metformin on Liver Aminotransferases in Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Double Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Int J Prev Med. 2013 May;4(5):531-7. | PubMed |

Shavakhi A, Minakari M, Firouzian H, Assali R, Hekmatdoost A, Ferns G. Effect of a Probiotic and Metformin on Liver Aminotransferases in Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Double Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Int J Prev Med. 2013 May;4(5):531-7. | PubMed | Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Diehl AM, Bass NM, et al. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 6;362(18):1675-85. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Diehl AM, Bass NM, et al. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 6;362(18):1675-85. | CrossRef | PubMed | Lutchman G, Modi A, Kleiner DE, Promrat K, Heller T, Ghany M, et al. The effects of discontinuing pioglitazone in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2007 Aug;46(2):424-9. | PubMed |

Lutchman G, Modi A, Kleiner DE, Promrat K, Heller T, Ghany M, et al. The effects of discontinuing pioglitazone in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2007 Aug;46(2):424-9. | PubMed | Aithal GP, Thomas JA, Kaye PV, Lawson A, Ryder SD, Spendlove I, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in nondiabetic subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2008 Oct;135(4):1176-84. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Aithal GP, Thomas JA, Kaye PV, Lawson A, Ryder SD, Spendlove I, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in nondiabetic subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2008 Oct;135(4):1176-84. | CrossRef | PubMed | Aguilar-Olivos NE, Carrillo-Córdova D, Oria-Hernández J, Sánchez-Valle V, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Ramírez-Jaramillo M, et al. The nuclear receptor FXR, but not LXR, up-regulates bile acid transporter expression in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2015 Jul-Aug;14(4):487-93. | PubMed |

Aguilar-Olivos NE, Carrillo-Córdova D, Oria-Hernández J, Sánchez-Valle V, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Ramírez-Jaramillo M, et al. The nuclear receptor FXR, but not LXR, up-regulates bile acid transporter expression in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2015 Jul-Aug;14(4):487-93. | PubMed | Elias M, Jimenez-Castro M, Mendes-Braz M, Casillas-Ramírez A, PeraltaC. The current knowledge of the role of PPAR in hepatic Ischemia-reperfusion injury. PPAR Res. 2012;2012:802384. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Elias M, Jimenez-Castro M, Mendes-Braz M, Casillas-Ramírez A, PeraltaC. The current knowledge of the role of PPAR in hepatic Ischemia-reperfusion injury. PPAR Res. 2012;2012:802384. | CrossRef | PubMed | Corey KE, Vuppalanchi R, Wilson LA, Cummings OW, Chalasani N; NASH CRN. NASH resolution is associated with improvements in HDL and triglyceride levels but not improvement in LDL or non-HDL-C levels. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Feb;41(3):301-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Corey KE, Vuppalanchi R, Wilson LA, Cummings OW, Chalasani N; NASH CRN. NASH resolution is associated with improvements in HDL and triglyceride levels but not improvement in LDL or non-HDL-C levels. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Feb;41(3):301-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kargiotis K, Katsiki N, Athyros VG, Giouleme O, Patsiaoura K, et al. Effect of rosuvastatin on non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with metabolic syndrome and hypercholesterolaemia: a preliminary report. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2014 May;12(3):505-11. | PubMed |

Kargiotis K, Katsiki N, Athyros VG, Giouleme O, Patsiaoura K, et al. Effect of rosuvastatin on non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with metabolic syndrome and hypercholesterolaemia: a preliminary report. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2014 May;12(3):505-11. | PubMed | Gómez-Domínguez E, Gisbert JP, Moreno-Monteagudo JA, García-Buey L, Moreno-Otero R. A pilot study of atorvastatin treatment in dyslipemid, non-alcoholic fatty liver patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Jun 1;23(11):1643-7. | PubMed |

Gómez-Domínguez E, Gisbert JP, Moreno-Monteagudo JA, García-Buey L, Moreno-Otero R. A pilot study of atorvastatin treatment in dyslipemid, non-alcoholic fatty liver patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Jun 1;23(11):1643-7. | PubMed |