Key Words: vaccine, chickenpox, varicella, Epistemonikos, GRADE.

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Chickenpox is an infectious disease caused by varicella-zoster virus. Varicella vaccine is conventionally used for its prevention, and its administration seeks to reduce the onset of the disease and complications associated. However, there is still controversy about its effectiveness.

METHODS

We searched in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others. We extracted data from the systematic reviews, reanalyzed data of primary studies, conducted a meta-analysis and generated a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

We identified two systematic reviews including 16 studies overall, of which three were randomized trials. We concluded that the varicella vaccine decreases the risk of contracting the disease in the long term and probably reduces the risk of developing the disease in the short term in healthy unexposed patients. Nevertheless, the vaccination increases the occurrence of local reactions 48 hours after its administration and probably increases the presence of fever and chickenpox-like rash.

Problem

Chickenpox is an infectious disease caused by varicella-zoster virus. Most cases occur in childhood (under 14 years old), so it has been identified as an important cause of school absenteeism, generating significant expenses to the community [1] [2]. Chickenpox diagnosis is clinical, characterized by pruritic, vesicular, cephalocaudal, polymorph rash, with scalp involvement, generally associated to fever.

Usually, varicella vaccine is used for disease prevention, which is a live attenuated vaccine that induces humoral immune response. Its administration would prevent the onset of disease and its complications. However, there is still controversy regarding its effectiveness in reducing chickenpox in the short and long term.

Methods

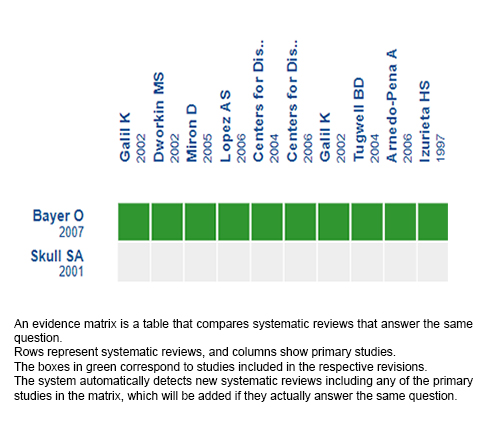

We searched in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others, to identify systematic reviews and their included primary studies. We extracted data from the identified reviews and reanalyzed data from primary studies included in those reviews. With this information, we generated a structured summary denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos) using a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), meta-analysis of the total of studies when it is possible, a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach and a table of other considerations for decision-making.

|

Key messages

|

About the body of evidence for this question

|

What is the evidence. |

We identified two systematic reviews [3], [4], which including 16 primary studies reported in 17 references [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [ 13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], of which two correspond to randomized trials reported in three references [19], [20], [21]. This table and the summary in general are based on the latter, since observational studies did not increase the certainty of existing evidence, nor did they provide additional relevant information. |

|

What types of patients were included* |

All trials included healthy patients, with no history of chickenpox or vaccination against the disease. One trial included patients between one and 14 years old [20], while the other trial included patients between 10 to 30 months old [21]. |

|

What types of interventions were included* |

All trials evaluated one dose of Oka strain varicella vaccine [20], [21]. Both trials compared vaccination against an unvaccinated control group [20], [21]. In addition, one of the trials included a comparison with no follow-up of the control group [20], so in this summary the authors decided to evaluate it assuming the worst case scenario, meaning that no one in the unvaccinated control group develop chicken pox in the follow-up years. |

|

What types of outcomes |

Trials reported multiple outcomes, which were grouped by systematic reviews as follows:

|

* Information about primary studies is not extracted directly from primary studies but from identified systematic reviews, unless otherwise stated.

Summary of findings

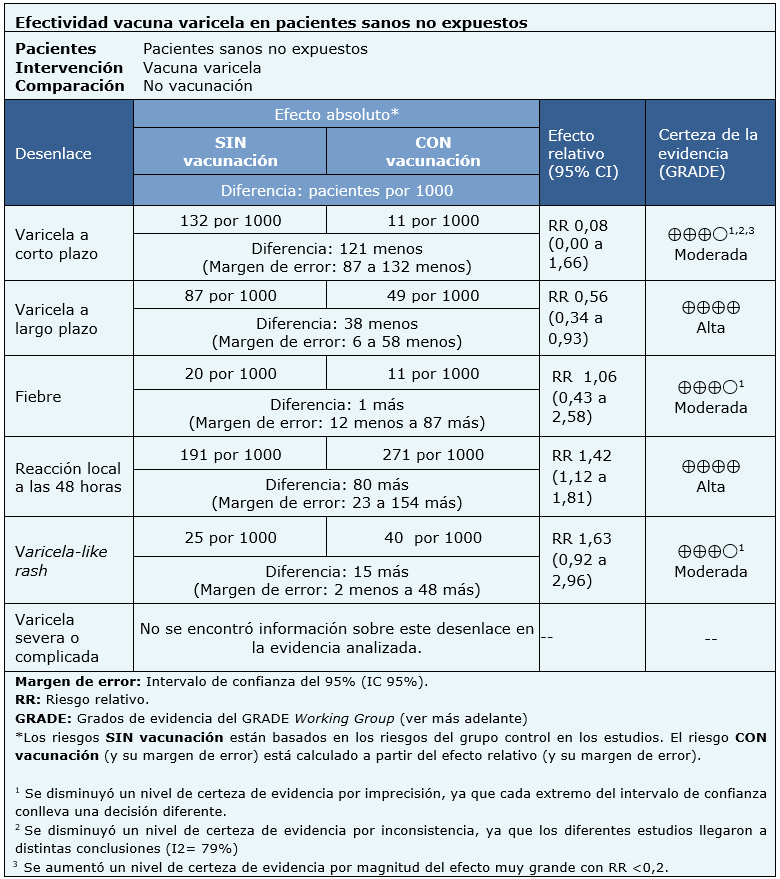

Information about varicella vaccine effects is based on two randomized trials that included 1449 patients.

Both trials measured short-term chickenpox and chickenpox-like rash as outcomes (1407 patients) [20], [21]. One of the trials measured long-term chickenpox, fever and local reactions (914 patients) [20]. No trial reported the outcome severe or complicated chickenpox.

The summary of findings is as follows:

- Vaccination against chickenpox probably decreases the risk of developing the disease in the short term (moderate certainty evidence).

- Vaccination against chickenpox decreases the risk of developing the disease in the long term (high certainty evidence).

- Vaccination against chickenpox probably results in little or no difference in the onset of fever after administration (moderate certainty evidence).

- Vaccination against chickenpox increases the occurrence of local reactions within 48 hours after administration (high certainty evidence).

- Vaccination against chickenpox probably increases the appearance of chickenpox-like rash after administration (moderate certainty evidence).

| Follow the link to access the interactive version of this table (Interactive Summary of Findings – iSoF) |

Other considerations for decision-making

|

To whom this evidence does and does not apply |

|

| About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

| Balance between benefits and risks, and certainty of the evidence |

|

| Resource considerations |

|

| What would patients and their doctors think about this intervention |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

| Could this evidence change in the future? |

|

How we conducted this summary

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Effectiveness of varicella vaccine in healthy unexposed patients.

Notes

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier.

After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrixes and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

This article is part of the Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis project. It is elaborated with a pre-established methodology, following rigorous methodological standards and internal peer review process. Each of these articles corresponds to a summary, denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos), whose main objective is to synthesize the body of evidence for a specific question, with a friendly format to clinical professionals. Its main resources are based on the evidence matrix of Epistemonikos and analysis of results using GRADE methodology. Further details of the methods for developing this FRISBEE are described here (http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997)

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database (www.epistemonikos.org).

Potential conflicts of interest

The authors do not have relevant interests to declare.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

INTRODUCCIÓN

La varicela es una enfermedad infectocontagiosa producida por el virus varicela-zóster. Para su prevención, convencionalmente se utiliza la vacuna varicela, cuya administración busca disminuir la aparición de enfermedad y sus complicaciones. Sin embargo, aún existe controversia sobre la efectividad.

MÉTODOS

Realizamos una búsqueda en Epistemonikos, la mayor base de datos de revisiones sistemáticas en salud, la cual es mantenida mediante el cribado de múltiples fuentes de información, incluyendo MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, entre otras. Extrajimos los datos desde las revisiones identificadas, analizamos los datos de los estudios primarios, realizamos un metanálisis y preparamos una tabla de resumen de los resultados utilizando el método GRADE.

RESULTADOS Y CONCLUSIONES

Se identificaron dos revisiones sistemáticas que en conjunto incluyeron 16 estudios primarios, de los cuales, tres corresponden a ensayos aleatorizados. Concluimos que la vacunación contra la varicela disminuye el riesgo de contraer la enfermedad a largo plazo en pacientes sanos sin exposición previa y que probablemente disminuye el riesgo de contraer la enfermedad a corto plazo. Sin embargo, aumenta la reacción local 48 horas posterior a su administración y probablemente aumenta la aparición de fiebre y varicela-like rash.

Authors:

María Catalina Castro[1,2], Pamela Rojas[2,3]

Authors:

María Catalina Castro[1,2], Pamela Rojas[2,3]

Affiliation:

[1] Facultad de Medicina, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile.

[2] Proyecto Epistemonikos, Santiago, Chile.

[3] Departamento de Medicina Familiar del Niño, Facultad de Medicina, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile.

E-mail: projasgo@uc.cl

Author address:

[1] Centro Evidencia UC Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Diagonal Paraguay 476 Santiago Chile

Citation: Castro M, Rojas P. Preventive effectiveness of varicella vaccine in healthy unexposed patients. Medwave 2020;20(06):e7982 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2020.06.7982

Submission date: 23/5/2019

Acceptance date: 28/11/2019

Publication date: 30/7/2020

Origin: This article is a product of the Evidence Synthesis Project of Epistemonikos Fundation, in collaboration with Medwave for its publication.

Type of review: Non-blinded peer review by members of the methodological team of Centro Evidencia UC in collaboration with the Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis.

Comments (0)

We are pleased to have your comment on one of our articles. Your comment will be published as soon as it is posted. However, Medwave reserves the right to remove it later if the editors consider your comment to be: offensive in some sense, irrelevant, trivial, contains grammatical mistakes, contains political harangues, appears to be advertising, contains data from a particular person or suggests the need for changes in practice in terms of diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic interventions, if that evidence has not previously been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No comments on this article.

To comment please log in

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics.

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics. There may be a 48-hour delay for most recent metrics to be posted.

- Choo P, Donahue J, Manson J, Platt R. The Epidemiology of Varicella and Its Complications. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1995;172(3):706-712.

- Yawn B, Yawn R, Lydick E. Community impact of childhood varicella infections. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1997;130(5):759-765.

- Bayer O, Heininger U, Heiligensetzer C, von Kries R. Metaanalysis of vaccine effectiveness in varicella outbreaks. Vaccine. 2007;25(37-38):6655-60.

- Skull SA, Wang EE. Varicella vaccination--a critical review of the evidence. Archives of disease in childhood. 2001;85(2):83-90.

- Galil K, Fair E, Mountcastle N, Britz P, Seward J. Younger age at vaccination may increase risk of varicella vaccine failure. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2002;186(1):102-5.

- Dworkin MS, Jennings CE, Roth-Thomas J, Lang JE, Stukenberg C, Lumpkin JR. An Outbreak of Varicella among children attending preschool and elementary school in Illinois. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2002;35(1):102-4.

- Miron D, Lavi I, Kitov R, Hendler A. Vaccine effectiveness and severity of varicella among previously vaccinated children during outbreaks in day-care centers with low vaccination coverage. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2005;24(3):233-6.

- Lopez AS, Guris D, Zimmerman L, et al.. One dose of varicella vaccine does not prevent school outbreaks: is it time for a second dose?. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6)(Available at: www. pediatrics. org/ cgi/ content/ full/ 117/ 6/ e1070).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Outbreak of varicella among vaccinated children--Michigan, 2003. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2004;53(18):389-92.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Varicella outbreak among vaccinated children— Nebraska, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly. 2006;55(27):749–752.

- Galil K, Lee B, Strine T, Carraher C, Baughman AL, Eaton M, Montero J, Seward J. Outbreak of varicella at a day-care center despite vaccination. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;347(24):1909-15.

- Tugwell BD, Lee LE, Gillette H, Lorber EM, Hedberg K, Cieslak PR. Chickenpox outbreak in a highly vaccinated school population. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):455-9.

- Arnedo-Pena A, Puig-Barberà J, Aznar-Orenga MA, Ballester-Albiol M, Pardo-Serrano F, Bellido-Blasco JB, Romeu-García MA. Varicella vaccine effectiveness during an outbreak in a partially vaccinated population in Spain. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2006;25(9):774-8.

- Izurieta HS, Strebel PM, Blake PA. Postlicensure effectiveness of varicella vaccine during an outbreak in a child care center. JAMA. 1997;278(18):1495-9.

- Buchholz U, Moolenaar R, Peterson C, Mascola L. Varicella outbreaks after vaccine licensure: should they make you chicken?. Pediatrics. 1999;104(3 Pt 1):561-3.

- Marin M, Nguyen HQ, Keen J, Jumaan AO, Mellen PM, Hayes EB, Gensheimer KF, Gunderman-King J, Seward JF. Importance of catch-up vaccination: experience from a varicella outbreak, Maine, 2002-2003. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):900-5.

- Lee BR, Feaver SL, Miller CA, Hedberg CW, Ehresmann KR. An elementary school outbreak of varicella attributed to vaccine failure: policy implications. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2004;190(3):477-83.

- Haddad MB, Hill MB, Pavia AT, Green CE, Jumaan AO, De AK, Rolfs RT. Vaccine effectiveness during a varicella outbreak among schoolchildren: Utah, 2002-2003. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1488-93.

- Kuter BJ, Weibel RE, Guess HA, Matthews H, Morton DH, Neff BJ, Provost PJ, Watson BA, Starr SE, Plotkin SA. Oka/Merck varicella vaccine in healthy children: final report of a 2-year efficacy study and 7-year follow-up studies. Vaccine. 1991;9(9):643-7.

- Weibel RE, Neff BJ, Kuter BJ, Guess HA, Rothenberger CA, Fitzgerald AJ, Connor KA, McLean AA, Hilleman MR, Buynak EB. Live attenuated varicella virus vaccine. Efficacy trial in healthy children. The New England journal of medicine. 1984;310(22):1409-15.

- Varis T, Vesikari T. Efficacy of high-titer live attenuated varicella vaccine in healthy young children. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1996;174 Suppl 3:S330-4.

- Cortés I, Pérez-Camarero S, Del Llano J, Peña LM, Hidalgo-Vega A. Systematic review of economic evaluation analyses of available vaccines in Spain from 1990 to 2012. Vaccine. 2013;31(35):3473-84.

- Unim B, Saulle R, Boccalini S, Taddei C, Ceccherini V, Boccia A, Bonanni P, La Torre G. Economic evaluation of Varicella vaccination: results of a systematic review. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2013;9(9):1932-42.

- Prevention of Varicella: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) [Internet]. Cdc.gov. 2019 [cited 22 March 2019]. | Link |

Choo P, Donahue J, Manson J, Platt R. The Epidemiology of Varicella and Its Complications. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1995;172(3):706-712.

Choo P, Donahue J, Manson J, Platt R. The Epidemiology of Varicella and Its Complications. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1995;172(3):706-712.  Yawn B, Yawn R, Lydick E. Community impact of childhood varicella infections. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1997;130(5):759-765.

Yawn B, Yawn R, Lydick E. Community impact of childhood varicella infections. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1997;130(5):759-765.  Bayer O, Heininger U, Heiligensetzer C, von Kries R. Metaanalysis of vaccine effectiveness in varicella outbreaks. Vaccine. 2007;25(37-38):6655-60.

Bayer O, Heininger U, Heiligensetzer C, von Kries R. Metaanalysis of vaccine effectiveness in varicella outbreaks. Vaccine. 2007;25(37-38):6655-60.  Skull SA, Wang EE. Varicella vaccination--a critical review of the evidence. Archives of disease in childhood. 2001;85(2):83-90.

Skull SA, Wang EE. Varicella vaccination--a critical review of the evidence. Archives of disease in childhood. 2001;85(2):83-90.  Galil K, Fair E, Mountcastle N, Britz P, Seward J. Younger age at vaccination may increase risk of varicella vaccine failure. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2002;186(1):102-5.

Galil K, Fair E, Mountcastle N, Britz P, Seward J. Younger age at vaccination may increase risk of varicella vaccine failure. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2002;186(1):102-5.  Dworkin MS, Jennings CE, Roth-Thomas J, Lang JE, Stukenberg C, Lumpkin JR. An Outbreak of Varicella among children attending preschool and elementary school in Illinois. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2002;35(1):102-4.

Dworkin MS, Jennings CE, Roth-Thomas J, Lang JE, Stukenberg C, Lumpkin JR. An Outbreak of Varicella among children attending preschool and elementary school in Illinois. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2002;35(1):102-4.  Miron D, Lavi I, Kitov R, Hendler A. Vaccine effectiveness and severity of varicella among previously vaccinated children during outbreaks in day-care centers with low vaccination coverage. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2005;24(3):233-6.

Miron D, Lavi I, Kitov R, Hendler A. Vaccine effectiveness and severity of varicella among previously vaccinated children during outbreaks in day-care centers with low vaccination coverage. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2005;24(3):233-6.  Lopez AS, Guris D, Zimmerman L, et al.. One dose of varicella vaccine does not prevent school outbreaks: is it time for a second dose?. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6)(Available at: www. pediatrics. org/ cgi/ content/ full/ 117/ 6/ e1070).

Lopez AS, Guris D, Zimmerman L, et al.. One dose of varicella vaccine does not prevent school outbreaks: is it time for a second dose?. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6)(Available at: www. pediatrics. org/ cgi/ content/ full/ 117/ 6/ e1070).  Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Outbreak of varicella among vaccinated children--Michigan, 2003. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2004;53(18):389-92.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Outbreak of varicella among vaccinated children--Michigan, 2003. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2004;53(18):389-92.  Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Varicella outbreak among vaccinated children— Nebraska, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly. 2006;55(27):749–752.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Varicella outbreak among vaccinated children— Nebraska, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly. 2006;55(27):749–752.  Galil K, Lee B, Strine T, Carraher C, Baughman AL, Eaton M, Montero J, Seward J. Outbreak of varicella at a day-care center despite vaccination. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;347(24):1909-15.

Galil K, Lee B, Strine T, Carraher C, Baughman AL, Eaton M, Montero J, Seward J. Outbreak of varicella at a day-care center despite vaccination. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;347(24):1909-15.  Tugwell BD, Lee LE, Gillette H, Lorber EM, Hedberg K, Cieslak PR. Chickenpox outbreak in a highly vaccinated school population. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):455-9.

Tugwell BD, Lee LE, Gillette H, Lorber EM, Hedberg K, Cieslak PR. Chickenpox outbreak in a highly vaccinated school population. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):455-9.  Arnedo-Pena A, Puig-Barberà J, Aznar-Orenga MA, Ballester-Albiol M, Pardo-Serrano F, Bellido-Blasco JB, Romeu-García MA. Varicella vaccine effectiveness during an outbreak in a partially vaccinated population in Spain. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2006;25(9):774-8.

Arnedo-Pena A, Puig-Barberà J, Aznar-Orenga MA, Ballester-Albiol M, Pardo-Serrano F, Bellido-Blasco JB, Romeu-García MA. Varicella vaccine effectiveness during an outbreak in a partially vaccinated population in Spain. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2006;25(9):774-8.  Izurieta HS, Strebel PM, Blake PA. Postlicensure effectiveness of varicella vaccine during an outbreak in a child care center. JAMA. 1997;278(18):1495-9.

Izurieta HS, Strebel PM, Blake PA. Postlicensure effectiveness of varicella vaccine during an outbreak in a child care center. JAMA. 1997;278(18):1495-9.  Buchholz U, Moolenaar R, Peterson C, Mascola L. Varicella outbreaks after vaccine licensure: should they make you chicken?. Pediatrics. 1999;104(3 Pt 1):561-3.

Buchholz U, Moolenaar R, Peterson C, Mascola L. Varicella outbreaks after vaccine licensure: should they make you chicken?. Pediatrics. 1999;104(3 Pt 1):561-3.  Marin M, Nguyen HQ, Keen J, Jumaan AO, Mellen PM, Hayes EB, Gensheimer KF, Gunderman-King J, Seward JF. Importance of catch-up vaccination: experience from a varicella outbreak, Maine, 2002-2003. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):900-5.

Marin M, Nguyen HQ, Keen J, Jumaan AO, Mellen PM, Hayes EB, Gensheimer KF, Gunderman-King J, Seward JF. Importance of catch-up vaccination: experience from a varicella outbreak, Maine, 2002-2003. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):900-5.  Lee BR, Feaver SL, Miller CA, Hedberg CW, Ehresmann KR. An elementary school outbreak of varicella attributed to vaccine failure: policy implications. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2004;190(3):477-83.

Lee BR, Feaver SL, Miller CA, Hedberg CW, Ehresmann KR. An elementary school outbreak of varicella attributed to vaccine failure: policy implications. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2004;190(3):477-83.  Haddad MB, Hill MB, Pavia AT, Green CE, Jumaan AO, De AK, Rolfs RT. Vaccine effectiveness during a varicella outbreak among schoolchildren: Utah, 2002-2003. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1488-93.

Haddad MB, Hill MB, Pavia AT, Green CE, Jumaan AO, De AK, Rolfs RT. Vaccine effectiveness during a varicella outbreak among schoolchildren: Utah, 2002-2003. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1488-93.  Kuter BJ, Weibel RE, Guess HA, Matthews H, Morton DH, Neff BJ, Provost PJ, Watson BA, Starr SE, Plotkin SA. Oka/Merck varicella vaccine in healthy children: final report of a 2-year efficacy study and 7-year follow-up studies. Vaccine. 1991;9(9):643-7.

Kuter BJ, Weibel RE, Guess HA, Matthews H, Morton DH, Neff BJ, Provost PJ, Watson BA, Starr SE, Plotkin SA. Oka/Merck varicella vaccine in healthy children: final report of a 2-year efficacy study and 7-year follow-up studies. Vaccine. 1991;9(9):643-7.  Weibel RE, Neff BJ, Kuter BJ, Guess HA, Rothenberger CA, Fitzgerald AJ, Connor KA, McLean AA, Hilleman MR, Buynak EB. Live attenuated varicella virus vaccine. Efficacy trial in healthy children. The New England journal of medicine. 1984;310(22):1409-15.

Weibel RE, Neff BJ, Kuter BJ, Guess HA, Rothenberger CA, Fitzgerald AJ, Connor KA, McLean AA, Hilleman MR, Buynak EB. Live attenuated varicella virus vaccine. Efficacy trial in healthy children. The New England journal of medicine. 1984;310(22):1409-15.  Varis T, Vesikari T. Efficacy of high-titer live attenuated varicella vaccine in healthy young children. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1996;174 Suppl 3:S330-4.

Varis T, Vesikari T. Efficacy of high-titer live attenuated varicella vaccine in healthy young children. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1996;174 Suppl 3:S330-4.  Cortés I, Pérez-Camarero S, Del Llano J, Peña LM, Hidalgo-Vega A. Systematic review of economic evaluation analyses of available vaccines in Spain from 1990 to 2012. Vaccine. 2013;31(35):3473-84.

Cortés I, Pérez-Camarero S, Del Llano J, Peña LM, Hidalgo-Vega A. Systematic review of economic evaluation analyses of available vaccines in Spain from 1990 to 2012. Vaccine. 2013;31(35):3473-84.  Unim B, Saulle R, Boccalini S, Taddei C, Ceccherini V, Boccia A, Bonanni P, La Torre G. Economic evaluation of Varicella vaccination: results of a systematic review. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2013;9(9):1932-42.

Unim B, Saulle R, Boccalini S, Taddei C, Ceccherini V, Boccia A, Bonanni P, La Torre G. Economic evaluation of Varicella vaccination: results of a systematic review. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2013;9(9):1932-42.  Prevention of Varicella: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) [Internet]. Cdc.gov. 2019 [cited 22 March 2019]. | Link |

Prevention of Varicella: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) [Internet]. Cdc.gov. 2019 [cited 22 March 2019]. | Link |Systematization of initiatives in sexual and reproductive health about good practices criteria in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in primary health care in Chile

Clinical, psychological, social, and family characterization of suicidal behavior in Chilean adolescents: a multiple correspondence analysis