Key Words: evidence- based medicine, decision support techniques, review literature as topic, systematic reviews as topic, review [Publication Type]

Abstract

This article is the first in a collaborative methodological series of narrative reviews on biostatistics and clinical epidemiology. This review aims to present rapid reviews, compare them with systematic reviews, and mention how they can be used. Rapid reviews use a methodology like systematic reviews, but through shortcuts applied, they can attain answers in less than six months and with fewer resources. Decision-makers use them in both America and Europe. There is no consensus on which shortcuts have the least impact on the reliability of conclusions, so rapid reviews are heterogeneous. Users of rapid reviews should identify these shortcuts in the methodology and be cautious when interpreting the conclusions, although they generally reach answers concordant with those obtained through a formal systematic review. The principal value of rapid reviews is to respond to health decision-makers’ needs when the context demands answers in limited time frames.

Introduction

Systematic reviews are currently considered the best option to offer informed decisions[1] for clinicians and health decision-makers due to their ability to synthesize relevant scientific evidence on a subject, with high methodological standards in their process. However, the process is expensive and slow and can take over three years to complete[2], which can delay the questions posed for a long time, potentially affecting clinical decision-making and health policy design.

Rapid reviews arise to synthesize the knowledge with the components of a systematic review but are simplified or omitted to produce information in less time and fewer resources to meet the needs of decision-makers[3],[4]. These simplified processes are known as “shortcuts” and, while they could decrease reliability in the conclusions[5], studies concluded that, especially in therapeutic interventions, they do not change the result drastically[6],[7].

Without a universal definition, rapid reviews are presented as a heterogeneous set of products without standardization in their production[8]. Neither it is known which shortcuts would cause less impact to their quality[9]. There is an agreement to consider a rapid review as requiring from one to six months for production according to the needs of decision-makers[10], which has increased their demand and led organizations such as the World Health Organization to use these methods for the preparation of guides in a limited time[11],[12], and the Cochrane Collaboration to establish a working group on rapid reviews in 2015.

This article corresponds to the first in a methodological series of narrative reviews on general topics in biostatistics and clinical epidemiology that explore and summarize, in an accessible language, published articles available via the main databases and specialized consultation texts. The series is aimed at the training of undergraduate students. The Evidence-Based Medicine department from the School of Medicine of the Universidad de Valparaiso, Chile, in collaboration with the Research Department of Instituto Universitario Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina, and the Evidence Center UC, of the Universidad Católica, Chile have worked on the series. The main purpose of this article is to introduce the concept of rapid reviews, their similarities and differences with systematic reviews, and their usefulness as a tool to synthesize evidence with fewer resources.

General concepts of systematic reviews

Systematic reviews are the best evidence-synthesis design to achieve reliable conclusions[13], especially when designing public policies or clinical practice guidelines[14].

A good quality systematic review should have an explicit protocol established “a priori” and ideally kept unchanged during the process, which will allow evaluators to reproduce the process and make a critical analysis of its methodology[5]. This protocol should be enrolled in a specialized registration database, such as PROSPERO, or published in scientific journals.

The research question must be well structured (in PICO format)[15], clinically relevant, and possess a scope and complexity determined by the authors according to the needs of stakeholders[8]. The search strategy should be comprehensive and have high sensitivity, covering multiple electronic databases with published studies, documents not yet published in conventional channels (grey literature), journal publications or scientific societies, and sometimes even reaching out to experts to look for ongoing studies. This search requires many resources to access eligible studies[9].

The inclusion and exclusion of studies and the critical assessment of the risk of bias includes at least two independent reviewers[15]. Therefore, the time it takes to complete the process depends on the amount of evidence found, the studies selected by the reviewers that require full-text evaluation, and the extraction of their results.

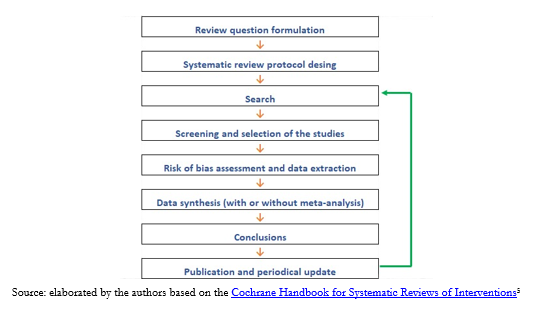

We can outline the process in the following steps (Figure 1):

Figure 1. Steps to conduct a systematic review.

It is then necessary to know what stages of a systematic review can be simplified and what implications these shortcuts have in the conclusions achieved[13].

Rapid reviews

Currently, rapid reviews are used to develop public health policies in the Americas and Europe[5],[16]: health technology assessment reports conducted in Latin America are examples of the rise of this type of methodological design. Locally, the Epistemonikos[17] and LOVE[18],[19] initiative stand out as facilitators in the search for rapid reviews[20]. The ability to balance an abbreviated process with sufficient methodological rigor results in rapid reviews becoming a real alternative to evidence synthesis operating on moderate information confidence within limited timeframes[10].

Nonetheless, the authors must explain the methodological limitations and the consequent risk of design bias[21],[22]. Readers of these abbreviated syntheses should be cautious when analyzing the methodology and the shortcuts used by reviewers, taking into account the authors’ confidence in their conclusions[6].

Due to the lack of consensus on defining them, rapid reviews are challenging to identify if their titles are not explicit. Most of them are found in the grey literature[5]. Also, because they are directly commissioned by stakeholders such as ministries of health or policy-makers[5], many are not in the public domain.

The shortcuts used by the authors of the different published rapid reviews are inconsistent, which creates a high heterogeneity in this type of evidence synthesis. Further studies are needed to properly assess which parts of a systematic review process can be simplified to have the least impact on their conclusions[10]. However, when a rapid review includes at least ten studies, it is less likely to lead to different conclusions than those achieved from a traditional systematic review[6].

As mentioned, rapid review methods are not standardized. Notwithstanding, PRISMA, a project that seeks to standardize the reporting of systematic reviews, has been updating and incorporating formats such as rapid reviews since 2018[23].

Review record

While databases such as PROSPERO accept the registration of rapid review protocols, not all consider this step in their production[21]. Failure to register or publish the protocol increases the risk of reporting bias[15].

Review question

Rapid reviews use a question with a PICO structure but should have a specific scope and not become a quick alternative to a systematic review[24]. The question must be specific or have a limited scope considering the stakeholders’ objectives[10]. The objective will largely determine the time the review takes. Some topics beyond the reach of rapid reviews require multiple or complex interventions[8].

Bibliographic search

As a first step, authors can look for a high-quality systematic review to avoid duplication of effort and redirect to a quick update of the review; for example, the authors can search from the review’s search date a small number of databases. This abbreviated search can be carried out in one of the leading electronic bibliographic sources, with PubMed/MEDLINE being the most widely used[25] given that it includes, on average, more than 80% of the studies usually included in systematic reviews[6].

Other shortcuts used to simplify the search include:

● Removing manual search for evidence (non-electronic sources) and gray literature[5].

● Limiting the search to studies in specific languages[5],[26], for example, only studies published in English.

● Limiting the studies’ publication date search for publications in the last ten years, for example[5]. This shortcut is the most used by published rapid reviews[21].

● Limiting the design of eligible studies by, for example, by limiting the search to randomized clinical trials[8].

These shortcuts may increase the risk of publication bias and selection bias[6],[10].

Study selection and data extraction

Authors may decide not to perform duplicate data collection and extraction[10]. This decision can speed up a rapid review; however, both steps will have a higher risk of error and bias[27],[28],[29]. Another shortcut used in this step is to include fewer outcomes when selecting the studies[9], for example, to consider only mortality as a relevant outcome. One disadvantage of this shortcut is that assessing potential selective reporting of outcomes of a primary study is lost.

Risk of bias assessment

Some rapid reviews omit the risk of bias assessment as a shortcut; however, this is not recommended due to the high impact on the reliability of the conclusions[30],[31]. By not conducting a critical appraisal, the quality of the evidence on which the conclusions are formulated is unknown[32],[33].

Synthesis of the evidence

Rapid reviews may choose not to conduct a meta-analysis, and only narratively describe quantitative findings; in fact, more than two-thirds of rapid reviews present their results this way[21].

Conclusions of a rapid review

Because available evidence is limited, few studies have evaluated the robustness of rapid reviews[9]. Some studies have found that the conclusions of rapid reviews do not differ substantially from a traditional systematic review[5],[24]. Due to the limitations that shortcuts may cause, the conclusions’ reliability is lower[9], and thus they must be interpreted by their consumers. Reliability will also depend on the quality of the studies included in each rapid review[32],[33].

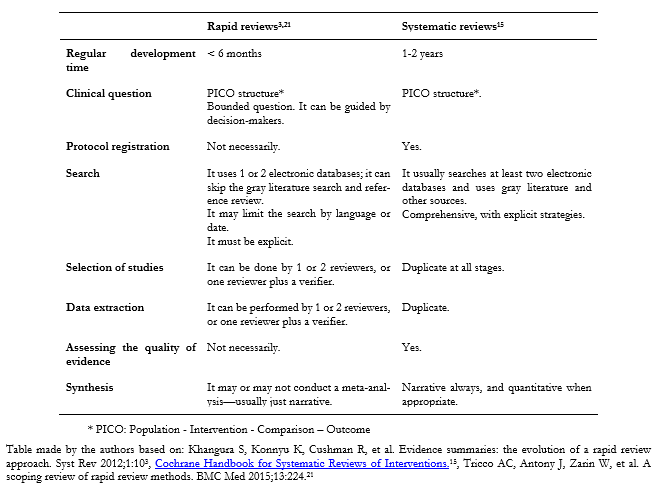

Below is a comparative table with the main differences between a systematic review and a rapid review (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison between a systematic review and a rapid review.

When is a rapid review helpful?

Considering all of the above, it is clear that rapid reviews’ methodological design is not appropriate in all contexts. Below we mention some circumstances in which they are:

● When there are time restrictions for conducting a synthesis of evidence, as in health contingencies such as the one presented during the COVID-19 pandemic[4].

● When there are resource restrictions, whether economic or human, to carry out a synthesis of evidence on a specific topic.

● Health centers that evaluate their service beyond healthcare, such as comparing the amount of litigation derived from their services with rates presented by other local or international centers[34].

● To evaluate new evidence on a topic when there is a broad consensus.

● And, in general, in any case where decision-makers—clinicians or health policy-makers—can act based on a less reliable synthesis of the evidence to respond to tight timeframes[10].

Some limitations of rapid reviews

It must be noted that a systematic review can be carried out quickly, maintaining the methodological rigor that characterizes it[35],[36] without using shortcuts in its methodology. This is one of the main criticisms of the methodology of rapid reviews because today, technological tools allow for optimizing the human resource and streamlining many of the processes of a systematic review[37],[38]. If there is access to sufficient resources (human, technological, economic), it would be best not to take shortcuts. Another criticism of rapid reviews is that they cannot address very specific clinical questions[30].

On the other hand, there are currently no standardized tools to evaluate the methodological quality of rapid reviews in contrast to tools such as ROBIS[39] and AMSTAR-2[40] that evaluate the methodological quality of systematic reviews.

Conclusions

Rapid reviews are abbreviated synthesis of evidence that contemplate the essential steps of a traditional systematic review but simplify or omit steps in the process to achieve results faster and with fewer resources. They do not have a consensus definition, and to date, there are no guidelines used widely, which makes them methodologically heterogeneous. The quality of rapid reviews depends directly on the shortcuts that have been implemented and how they may affect the results.

Rapid reviews are becoming more common due to their ability to answer specific questions within six months; however, they should be interpreted critically due to the methodology’s limitations. Authors should explain their methods, list the shortcuts used, and warn of possible biases present. With this in consideration, rapid reviews generally achieve results consistent with those obtained by a traditional systematic review, although with lower reliability.

Rapid reviews are booming, and the design will likely be standardized in the coming years. Rapid reviews may become one of the best tools to answer specific and relevant questions in health decision-making.

Notes

Roles and contributions

LTB: participated in conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, original writing and editing, and visualization. LVM: participated in conceptualization, investigation, resources, original writing and editing, and visualization. LG, LOM, CL y MV: participated in conceptualization, edition, visualization, supervision.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have completed the conflict of interest of ICMJE and declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Source of financial support

There was no funding for this review.

From the editors

The version of this manuscript that was peer-reviewed was submitted in Spanish. This English version was submitted by the authors and has been copyedited by the Journal.

Figure 1. Steps to conduct a systematic review.

Figure 1. Steps to conduct a systematic review.

Table 1. Comparison between a systematic review and a rapid review.

Table 1. Comparison between a systematic review and a rapid review.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Este artículo es el primero de una serie metodológica colaborativa de revisiones narrativas sobre temáticas de bioestadística y epidemiología clínica. El objetivo de esta revisión es presentar las revisiones rápidas, compararlas con las revisiones sistemáticas y mencionar su uso actual. Las revisiones rápidas utilizan una metodología similar a las revisiones sistemáticas, pero mediante atajos utilizados en su desarrollo; permiten alcanzar respuestas en menos de seis meses y con menos recursos, por lo que son utilizadas por tomadores de decisiones tanto en América como Europa. No existe consenso sobre cuáles atajos tienen menor impacto en la confiabilidad de las conclusiones, por lo que las revisiones rápidas son heterogéneas entre sí. Los consumidores deben identificar estos atajos en la metodología y ser precavidos en la interpretación de las conclusiones, aunque generalmente alcanzan respuestas concordantes con las obtenidas mediante una revisión sistemática tradicional. Su principal atractivo es ajustarse a las necesidades de los tomadores de decisiones en salud, cuando el contexto exige respuestas en plazos de tiempo acotados.

Authors:

Luis Tapia-Benavente[1], Laura Vergara-Merino[1,2], Luis Ignacio Garegnani[3], Luis Ortiz-Muñoz[4], Cristóbal Loézar Hernández[1,2], Manuel Vargas-Peirano[1,2]

Authors:

Luis Tapia-Benavente[1], Laura Vergara-Merino[1,2], Luis Ignacio Garegnani[3], Luis Ortiz-Muñoz[4], Cristóbal Loézar Hernández[1,2], Manuel Vargas-Peirano[1,2]

Affiliation:

[1] Escuela de Medicina, Universidad de Valparaíso (MEDUV), Valparaíso, Chile

[2] Centro Interdisciplinario de Estudios en Salud (CIESAL), Universidad de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile

[3] Centro Cochrane Asociado Instituto Universitario Hospital Italiano, Buenos Aires, Argentina

[4] Centro Evidencia UC, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

E-mail: manuel.vargas@uv.cl

Author address:

[1] Angamos 655, Viña del Mar, Chile Código Postal: 2540064

Citation: Tapia-Benavente L, Vergara-Merino L, Garegnani LI, Ortiz-Muñoz L, Loézar Hernández C, Vargas-Peirano M. Rapid reviews: definitions and uses. Medwave 2021;21(01):e8090 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2021.01.8090

Submission date: 25/9/2020

Acceptance date: 28/10/2020

Publication date: 5/1/2021

Origin: Not commissioned

Type of review: Externally peer-reviewed by three reviewers, double-blind

Comments (0)

We are pleased to have your comment on one of our articles. Your comment will be published as soon as it is posted. However, Medwave reserves the right to remove it later if the editors consider your comment to be: offensive in some sense, irrelevant, trivial, contains grammatical mistakes, contains political harangues, appears to be advertising, contains data from a particular person or suggests the need for changes in practice in terms of diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic interventions, if that evidence has not previously been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No comments on this article.

To comment please log in

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics.

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics. There may be a 48-hour delay for most recent metrics to be posted.

- Young C, Horton R. Putting clinical trials into context. Lancet. 2005 Jul 9-15;366(9480):107-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Borah R, Brown AW, Capers PL, Kaiser KA. Analysis of the time and workers needed to conduct systematic reviews of medical interventions using data from the PROSPERO registry. BMJ Open. 2017 Feb 27;7(2):e012545. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012 Feb 10;1:10. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Tricco AC, Garritty CM, Boulos L, Lockwood C, Wilson M, McGowan J, et al. Rapid review methods more challenging during COVID-19: commentary with a focus on 8 knowledge synthesis steps. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020 Oct;126:177-183. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Garritty C, Stevens A, Gartlehner G, King V, Kamel C. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group to play a leading role in guiding the production of informed high-quality, timely research evidence syntheses. Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 28;5(1):184. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Halladay CW, Trikalinos TA, Schmid IT, Schmid CH, Dahabreh IJ. Using data sources beyond PubMed has a modest impact on the results of systematic reviews of therapeutic interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015 Sep;68(9):1076-84. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Westphal A, Kriston L, Hölzel LP, Härter M, von Wolff A. Efficiency and contribution of strategies for finding randomized controlled trials: a case study from a systematic review on therapeutic interventions of chronic depression. J Public Health Res. 2014 Jul 1;3(2):177. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Featherstone RM, Dryden DM, Foisy M, Guise JM, Mitchell MD, Paynter RA, et al. Advancing knowledge of rapid reviews: an analysis of results, conclusions and recommendations from published review articles examining rapid reviews. Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 17;4:50. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Harker J, Kleijnen J. What is a rapid review? A methodological exploration of rapid reviews in Health Technology Assessments. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2012 Dec;10(4):397-410. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Haby MM, Chapman E, Clark R, Barreto J, Reveiz L, Lavis JN. What are the best methodologies for rapid reviews of the research evidence for evidence- informed decision making in health policy and practice: a rapid review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016 Nov 25;14(1):83. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Hersi M, Stevens A, Quach P, Hamel C, Thavorn K, Garritty C, et al. Effectiveness of Personal Protective Equipment for Healthcare Workers Caring for Patients with Filovirus Disease: A Rapid Review. PLoS One. 2015 Oct 9;10(10):e0140290. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- GRC Handbook - second edition. [On line] | Link |

- Nussbaumer-Streit B, Klerings I, Wagner G, Heise TL, Dobrescu AI, Armijo-Olivo S, et al. Abbreviated literature searches were viable alternatives to comprehensive searches: a meta epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018 Oct;102:1-11. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Zechmeister I, Schumacher I. The impact of health technology assessment reports on decision making in Austria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012 Jan;28(1):77-84. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. [On line] | Link |

- Vallejos C, Bustos L, de la Puente C, Reveco R, Velásquez M, Zaror C. Principales aspectos metodológicos en la Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias [The main methodological aspects in Health Technology Assessment]. Rev Med Chil. 2014 Jan;142 Suppl 1:S16-21. Spanish. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Rada G, Pérez D, Capurro D. Epistemonikos: a free, relational, collaborative, multilingual database of health evidence. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:486-90. | PubMed |

- Elliott JH, Turner T, Clavisi O, Thomas J, Higgins JP, Mavergames C, et al. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence- practice gap. PLoS Med. 2014 Feb 18;11(2):e1001603. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Elliott JH, Synnot A, Turner T, Simmonds M, Akl EA, McDonald S, et al. Living systematic review: 1. Introduction-the why, what, when, and how. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Nov;91:23-30. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Rada G. [Quick evidence reviews using Epistemonikos: a thorough, friendly and current approach to evidence in health]. Medwave 2014;14:e5997. | CrossRef |

- Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015 Sep 16;13:224. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Mulrow CD. The medical review article: state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Mar;106(3):485-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Stevens A, Garritty C, Hersi M, et al. Developing PRISMA-RR, a reporting guideline for rapid reviews of primary studies (Protocol). 2018. [On line] | Link |

- Watt A, Cameron A, Sturm L, Lathlean T, Babidge W, Blamey S, et al. Rapid reviews versus full systematic reviews: an inventory of current methods and practice in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2008 Spring;24(2):133-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Glujovsky D, Blake D, Farquhar C, Bardach A. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jul 11; (7):CD002118. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Moher D, Pham B, Lawson ML, Klassen TP. The inclusion of reports of randomised trials published in languages other than English in systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(41):1-90. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Buscemi N, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, Tjosvold L, Klassen TP. Single data extraction generated more errors than double data extraction in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006 Jul;59(7):697-703. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Jones AP, Remmington T, Williamson PR, Ashby D, Smyth RL. High prevalence but low impact of data extraction and reporting errors were found in Cochrane systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Jul;58(7):741-2. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Maric K, Tendal B. Data extraction errors in meta-analyses that use standardized mean differences. JAMA. 2007 Jul 25;298(4):430-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Abrami PC, Borokhovski E, Bernard RM, et al. Issues in conducting and disseminating brief reviews of evidence. Evid Policy 2010;6:371–89. | CrossRef |

- Polisena J, Garritty C, Umscheid CA, Kamel C, Samra K, Smith J, et al. Rapid Review Summit: an overview and initiation of a research agenda. Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 26;4:111. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Kilkenny MF, Robinson KM. Data quality: "Garbage in - garbage out". Health Inf Manag. 2018 Sep;47(3):103-105. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Egger M, Smith GD, Sterne JA. Uses and abuses of meta-analysis. Clin Med (Lond). 2001 Nov Dec;1(6):478-84. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Antony J, Zarin W, Pham B, Nincic V, Cardoso R, Ivory JD, et al. Patient safety initiatives in obstetrics: a rapid review. BMJ Open. 2018 Jul 6;8(7):e020170. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Schünemann HJ, Moja L. Reviews: Rapid! Rapid! Rapid! …and systematic. Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 14;4(1):4. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Clark J, Glasziou P, Del Mar C, Bannach-Brown A, Stehlik P, Scott AM. A full systematic review was completed in 2 weeks using automation tools: a case study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020 May;121:81-90. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Marshall IJ, Wallace BC. Toward systematic review automation: a practical guide to using machine learning tools in research synthesis. Syst Rev. 2019 Jul 11;8(1):163. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- van Altena AJ, Spijker R, Olabarriaga SD. Usage of automation tools in systematic reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2019 Mar;10(1):72-82. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, Shea B, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Jan;69:225-34. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017 Sep 21;358:j4008. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Young C, Horton R. Putting clinical trials into context. Lancet. 2005 Jul 9-15;366(9480):107-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Young C, Horton R. Putting clinical trials into context. Lancet. 2005 Jul 9-15;366(9480):107-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Borah R, Brown AW, Capers PL, Kaiser KA. Analysis of the time and workers needed to conduct systematic reviews of medical interventions using data from the PROSPERO registry. BMJ Open. 2017 Feb 27;7(2):e012545. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Borah R, Brown AW, Capers PL, Kaiser KA. Analysis of the time and workers needed to conduct systematic reviews of medical interventions using data from the PROSPERO registry. BMJ Open. 2017 Feb 27;7(2):e012545. | CrossRef | PubMed | Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012 Feb 10;1:10. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012 Feb 10;1:10. | CrossRef | PubMed | Tricco AC, Garritty CM, Boulos L, Lockwood C, Wilson M, McGowan J, et al. Rapid review methods more challenging during COVID-19: commentary with a focus on 8 knowledge synthesis steps. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020 Oct;126:177-183. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tricco AC, Garritty CM, Boulos L, Lockwood C, Wilson M, McGowan J, et al. Rapid review methods more challenging during COVID-19: commentary with a focus on 8 knowledge synthesis steps. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020 Oct;126:177-183. | CrossRef | PubMed | Garritty C, Stevens A, Gartlehner G, King V, Kamel C. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group to play a leading role in guiding the production of informed high-quality, timely research evidence syntheses. Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 28;5(1):184. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Garritty C, Stevens A, Gartlehner G, King V, Kamel C. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group to play a leading role in guiding the production of informed high-quality, timely research evidence syntheses. Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 28;5(1):184. | CrossRef | PubMed | Halladay CW, Trikalinos TA, Schmid IT, Schmid CH, Dahabreh IJ. Using data sources beyond PubMed has a modest impact on the results of systematic reviews of therapeutic interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015 Sep;68(9):1076-84. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Halladay CW, Trikalinos TA, Schmid IT, Schmid CH, Dahabreh IJ. Using data sources beyond PubMed has a modest impact on the results of systematic reviews of therapeutic interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015 Sep;68(9):1076-84. | CrossRef | PubMed | Westphal A, Kriston L, Hölzel LP, Härter M, von Wolff A. Efficiency and contribution of strategies for finding randomized controlled trials: a case study from a systematic review on therapeutic interventions of chronic depression. J Public Health Res. 2014 Jul 1;3(2):177. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Westphal A, Kriston L, Hölzel LP, Härter M, von Wolff A. Efficiency and contribution of strategies for finding randomized controlled trials: a case study from a systematic review on therapeutic interventions of chronic depression. J Public Health Res. 2014 Jul 1;3(2):177. | CrossRef | PubMed | Featherstone RM, Dryden DM, Foisy M, Guise JM, Mitchell MD, Paynter RA, et al. Advancing knowledge of rapid reviews: an analysis of results, conclusions and recommendations from published review articles examining rapid reviews. Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 17;4:50. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Featherstone RM, Dryden DM, Foisy M, Guise JM, Mitchell MD, Paynter RA, et al. Advancing knowledge of rapid reviews: an analysis of results, conclusions and recommendations from published review articles examining rapid reviews. Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 17;4:50. | CrossRef | PubMed | Harker J, Kleijnen J. What is a rapid review? A methodological exploration of rapid reviews in Health Technology Assessments. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2012 Dec;10(4):397-410. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Harker J, Kleijnen J. What is a rapid review? A methodological exploration of rapid reviews in Health Technology Assessments. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2012 Dec;10(4):397-410. | CrossRef | PubMed | Haby MM, Chapman E, Clark R, Barreto J, Reveiz L, Lavis JN. What are the best methodologies for rapid reviews of the research evidence for evidence- informed decision making in health policy and practice: a rapid review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016 Nov 25;14(1):83. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Haby MM, Chapman E, Clark R, Barreto J, Reveiz L, Lavis JN. What are the best methodologies for rapid reviews of the research evidence for evidence- informed decision making in health policy and practice: a rapid review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016 Nov 25;14(1):83. | CrossRef | PubMed | Hersi M, Stevens A, Quach P, Hamel C, Thavorn K, Garritty C, et al. Effectiveness of Personal Protective Equipment for Healthcare Workers Caring for Patients with Filovirus Disease: A Rapid Review. PLoS One. 2015 Oct 9;10(10):e0140290. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hersi M, Stevens A, Quach P, Hamel C, Thavorn K, Garritty C, et al. Effectiveness of Personal Protective Equipment for Healthcare Workers Caring for Patients with Filovirus Disease: A Rapid Review. PLoS One. 2015 Oct 9;10(10):e0140290. | CrossRef | PubMed | Nussbaumer-Streit B, Klerings I, Wagner G, Heise TL, Dobrescu AI, Armijo-Olivo S, et al. Abbreviated literature searches were viable alternatives to comprehensive searches: a meta epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018 Oct;102:1-11. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Nussbaumer-Streit B, Klerings I, Wagner G, Heise TL, Dobrescu AI, Armijo-Olivo S, et al. Abbreviated literature searches were viable alternatives to comprehensive searches: a meta epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018 Oct;102:1-11. | CrossRef | PubMed | Zechmeister I, Schumacher I. The impact of health technology assessment reports on decision making in Austria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012 Jan;28(1):77-84. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Zechmeister I, Schumacher I. The impact of health technology assessment reports on decision making in Austria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012 Jan;28(1):77-84. | CrossRef | PubMed | Vallejos C, Bustos L, de la Puente C, Reveco R, Velásquez M, Zaror C. Principales aspectos metodológicos en la Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias [The main methodological aspects in Health Technology Assessment]. Rev Med Chil. 2014 Jan;142 Suppl 1:S16-21. Spanish. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Vallejos C, Bustos L, de la Puente C, Reveco R, Velásquez M, Zaror C. Principales aspectos metodológicos en la Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias [The main methodological aspects in Health Technology Assessment]. Rev Med Chil. 2014 Jan;142 Suppl 1:S16-21. Spanish. | CrossRef | PubMed | Rada G, Pérez D, Capurro D. Epistemonikos: a free, relational, collaborative, multilingual database of health evidence. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:486-90. | PubMed |

Rada G, Pérez D, Capurro D. Epistemonikos: a free, relational, collaborative, multilingual database of health evidence. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:486-90. | PubMed | Elliott JH, Turner T, Clavisi O, Thomas J, Higgins JP, Mavergames C, et al. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence- practice gap. PLoS Med. 2014 Feb 18;11(2):e1001603. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Elliott JH, Turner T, Clavisi O, Thomas J, Higgins JP, Mavergames C, et al. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence- practice gap. PLoS Med. 2014 Feb 18;11(2):e1001603. | CrossRef | PubMed | Elliott JH, Synnot A, Turner T, Simmonds M, Akl EA, McDonald S, et al. Living systematic review: 1. Introduction-the why, what, when, and how. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Nov;91:23-30. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Elliott JH, Synnot A, Turner T, Simmonds M, Akl EA, McDonald S, et al. Living systematic review: 1. Introduction-the why, what, when, and how. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Nov;91:23-30. | CrossRef | PubMed | Rada G. [Quick evidence reviews using Epistemonikos: a thorough, friendly and current approach to evidence in health]. Medwave 2014;14:e5997. | CrossRef |

Rada G. [Quick evidence reviews using Epistemonikos: a thorough, friendly and current approach to evidence in health]. Medwave 2014;14:e5997. | CrossRef | Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015 Sep 16;13:224. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015 Sep 16;13:224. | CrossRef | PubMed | Mulrow CD. The medical review article: state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Mar;106(3):485-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Mulrow CD. The medical review article: state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Mar;106(3):485-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Stevens A, Garritty C, Hersi M, et al. Developing PRISMA-RR, a reporting guideline for rapid reviews of primary studies (Protocol). 2018. [On line] | Link |

Stevens A, Garritty C, Hersi M, et al. Developing PRISMA-RR, a reporting guideline for rapid reviews of primary studies (Protocol). 2018. [On line] | Link | Watt A, Cameron A, Sturm L, Lathlean T, Babidge W, Blamey S, et al. Rapid reviews versus full systematic reviews: an inventory of current methods and practice in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2008 Spring;24(2):133-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Watt A, Cameron A, Sturm L, Lathlean T, Babidge W, Blamey S, et al. Rapid reviews versus full systematic reviews: an inventory of current methods and practice in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2008 Spring;24(2):133-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Glujovsky D, Blake D, Farquhar C, Bardach A. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jul 11; (7):CD002118. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Glujovsky D, Blake D, Farquhar C, Bardach A. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jul 11; (7):CD002118. | CrossRef | PubMed | Moher D, Pham B, Lawson ML, Klassen TP. The inclusion of reports of randomised trials published in languages other than English in systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(41):1-90. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Moher D, Pham B, Lawson ML, Klassen TP. The inclusion of reports of randomised trials published in languages other than English in systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(41):1-90. | CrossRef | PubMed | Buscemi N, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, Tjosvold L, Klassen TP. Single data extraction generated more errors than double data extraction in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006 Jul;59(7):697-703. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Buscemi N, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, Tjosvold L, Klassen TP. Single data extraction generated more errors than double data extraction in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006 Jul;59(7):697-703. | CrossRef | PubMed | Jones AP, Remmington T, Williamson PR, Ashby D, Smyth RL. High prevalence but low impact of data extraction and reporting errors were found in Cochrane systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Jul;58(7):741-2. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Jones AP, Remmington T, Williamson PR, Ashby D, Smyth RL. High prevalence but low impact of data extraction and reporting errors were found in Cochrane systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Jul;58(7):741-2. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Maric K, Tendal B. Data extraction errors in meta-analyses that use standardized mean differences. JAMA. 2007 Jul 25;298(4):430-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Maric K, Tendal B. Data extraction errors in meta-analyses that use standardized mean differences. JAMA. 2007 Jul 25;298(4):430-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Abrami PC, Borokhovski E, Bernard RM, et al. Issues in conducting and disseminating brief reviews of evidence. Evid Policy 2010;6:371–89. | CrossRef |

Abrami PC, Borokhovski E, Bernard RM, et al. Issues in conducting and disseminating brief reviews of evidence. Evid Policy 2010;6:371–89. | CrossRef | Polisena J, Garritty C, Umscheid CA, Kamel C, Samra K, Smith J, et al. Rapid Review Summit: an overview and initiation of a research agenda. Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 26;4:111. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Polisena J, Garritty C, Umscheid CA, Kamel C, Samra K, Smith J, et al. Rapid Review Summit: an overview and initiation of a research agenda. Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 26;4:111. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kilkenny MF, Robinson KM. Data quality: "Garbage in - garbage out". Health Inf Manag. 2018 Sep;47(3):103-105. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kilkenny MF, Robinson KM. Data quality: "Garbage in - garbage out". Health Inf Manag. 2018 Sep;47(3):103-105. | CrossRef | PubMed | Egger M, Smith GD, Sterne JA. Uses and abuses of meta-analysis. Clin Med (Lond). 2001 Nov Dec;1(6):478-84. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Egger M, Smith GD, Sterne JA. Uses and abuses of meta-analysis. Clin Med (Lond). 2001 Nov Dec;1(6):478-84. | CrossRef | PubMed | Antony J, Zarin W, Pham B, Nincic V, Cardoso R, Ivory JD, et al. Patient safety initiatives in obstetrics: a rapid review. BMJ Open. 2018 Jul 6;8(7):e020170. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Antony J, Zarin W, Pham B, Nincic V, Cardoso R, Ivory JD, et al. Patient safety initiatives in obstetrics: a rapid review. BMJ Open. 2018 Jul 6;8(7):e020170. | CrossRef | PubMed | Schünemann HJ, Moja L. Reviews: Rapid! Rapid! Rapid! …and systematic. Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 14;4(1):4. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Schünemann HJ, Moja L. Reviews: Rapid! Rapid! Rapid! …and systematic. Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 14;4(1):4. | CrossRef | PubMed | Clark J, Glasziou P, Del Mar C, Bannach-Brown A, Stehlik P, Scott AM. A full systematic review was completed in 2 weeks using automation tools: a case study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020 May;121:81-90. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Clark J, Glasziou P, Del Mar C, Bannach-Brown A, Stehlik P, Scott AM. A full systematic review was completed in 2 weeks using automation tools: a case study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020 May;121:81-90. | CrossRef | PubMed | Marshall IJ, Wallace BC. Toward systematic review automation: a practical guide to using machine learning tools in research synthesis. Syst Rev. 2019 Jul 11;8(1):163. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Marshall IJ, Wallace BC. Toward systematic review automation: a practical guide to using machine learning tools in research synthesis. Syst Rev. 2019 Jul 11;8(1):163. | CrossRef | PubMed | van Altena AJ, Spijker R, Olabarriaga SD. Usage of automation tools in systematic reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2019 Mar;10(1):72-82. | CrossRef | PubMed |

van Altena AJ, Spijker R, Olabarriaga SD. Usage of automation tools in systematic reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2019 Mar;10(1):72-82. | CrossRef | PubMed |Systematization of initiatives in sexual and reproductive health about good practices criteria in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in primary health care in Chile

Clinical, psychological, social, and family characterization of suicidal behavior in Chilean adolescents: a multiple correspondence analysis