Key Words: private finance initiative, hospitals, concessions, healthcare infrastructure, hospital-building programs, procurement, public bidding, public-private partnerships, value for money, public sector comparator

Abstract

CONTEXT

Public-private partnerships began under President Ricardo Lagos, driven by the need to provide roads and other hard facilities. Over time, they expanded into social concessions such as prisons and hospitals. During the Bachelet administration, the construction of two mid-sized hospitals of Santiago was tendered with private finance initiative. During the government of Sebastián Piñera, three more hospitals were tendered.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

This article critically examines the grounds on which social concessions have been introduced in different parts of the world. I argue that the there are two main rationales underlying the position of those favorable to concession arrangements: pragmatic reasons and ideological-utopian reasons. I refute the arguments related to closing the infrastructure gap, effect on public debt, transfer of risk to the private sector, greater efficiency of the private sector, freeing-up of public funds and quality of health care.

CONCLUSIONS

Review of the international literature does not yield evidence in favor of hospital concessions consistent with the principles and drivers that promote them. Quite the contrary, when the “Value for Money” methodology has been used, concessions have proven to decrease the overall capacity of the health system and to negatively affect quality of health care. I also note that there is a potential impact on intergenerational equity with projects that span for long periods, as is the case of hospital concessions. I conclude that, since there is no evidence base grounded on sound technical principles in favor of this policy, the real underlying reasons to promote private financing of public health infrastructure are ideological, and functional to market interests but not to collective preferences.

Context

In Chile, concessions in the field of hospital construction and operation were first proposed during the government of President Ricardo Lagos. This came on the heels of the successful outcomes of concessions for highway construction and maintenance. By the end of his term, President Ricardo Lagos left the replacement project for Hospital Salvador in Santiago practically ready, for the tender process to take place during the administration of his successor, Michelle Bachelet.

However, due to reasons based on the complexity of the undertaking ‒as well as equity issues and a lack of national experience with this modality [1]‒ the project was not pursued under the Bachelet administration, leaving health infrastructure construction through concessions on hold for quite some time. Nevertheless, by the end of her government term, the tender process was resumed for the construction of two new hospitals, and which were awarded to a Spanish company.

During the Bachelet government, it was proposed that these two hospitals would be a sort of pilot experience, given that they were lower complexity hospitals in underserved areas. Nevertheless, the planning left by her government to be taken-up by the next took into account the incorporation of several new hospital construction projects – building new replacement hospitals– through the hospital concessions modality. Moreover, the construction of several replacement hospitals was also included in the 2010 budget to be executed under the Sebastian Piñera administration, with a sectoral budget.

When the new administration took office it was immediately announced that –and in part justified by the earthquake on 27 February 2010‒ any new construction would be carried out using the concession modality. Construction of the Santiago South Health Network (Complejo Asistencial Red Sur, CARS) facilities was irreversibly halted, even when the terms of reference for the construction bids had already been approved by the Comptroller General of Chile; but no authorization was issued for the tender to proceed. At the same time, awarding the rights for construction of the Gustavo Fricke Hospital in Viña del Mar was stopped, although review of the proposals submitted during the public tender process had already been completed. Despite all the ground gained in the process, the Health Service Director for that sector was instructed to not sign the award decision.

In 2010, the Minister of Health during the government of Piñera announced that no more health facilities were to be built (neither hospitals nor outpatient general health centers) using the sectoral budget and that everything would be redirected toward private concessions: design, financing, and construction, even industrial services. Clinical management was excluded from the outsourcing arrangement with the private sector, in order to garner support from the Chilean Medical College for this investment policy ‒a political goal that was successfully accomplished.

Concomitantly, strong resistance began to boil-up against the Santiago South Health Network facilities and the Gustavo Fricke Hospital concessions, leading to a change in course regarding several projects that had been announced for private finance initiative. The change affected the Fricke Hospital, where all social and political players in the Valparaíso administrative region united for the project to be returned to how it had originally been devised or, in other words, for its construction to be financed through the public budget. In the case of the Santiago South Health Network facilities, although the project had not been awarded, it was decided to proceed with the replacement of the Exequiel Gonzalez Cortes Pediatric Hospital under the sectoral modality. The rest was dropped. Other hospitals were also included for construction through sectoral budgeting, such as in the case of the city of Angol as well as the announced construction of numerous high complexity hospitals and others grouped into clusters to make them more attractive for private investment ‒and which to date have not materialized. The three hospitals that are finally being built under the concessions modality are: Hospital de Antofagasta, Hospital del Salvador [2], and the Felix Bulnes Hospital. A few days after the end of his term, the government of Sebastian Piñera speeded-up the tender and award processes, casting a veil of doubt over the quality of the administrative tender process.

What are hospital concessions?

Hospital concessions are a form of social public-private partnership. Concessions are agreements made between the State and the private sector (they may be all or only some of these elements) for the design, financing, construction and operation of a service whose execution is guaranteed by the State. In turn, concessions can be separated into hard and soft. Hard concessions are concessions that imply the execution of public works not associated to constitutionally guaranteed social rights, such as highways, airports, bridges, ports, and so on. Soft concessions are concessions that, in addition to the construction of civil works, also include the provision of a public-type of service, such as urban public transport, healthcare, education, imprisonment and rehabilitation of convicts, among others.

In England, hospital concessions were known as PFIs (Private Finance Initiative). Internationally though, they are also known as PPPs (Public Private Partnerships). Public Private Partnerships traditionally covered a broad array of social and industrial services, such as wastewater treatment, yet in the nineties it also began applying to the construction and operation of public hospitals.

Public Private Partnerships are contractual forms between a government and a private entity, whereby the private party takes on a long-term commitment for the provision of services for public benefit or for public goods [3]. The key words here are ‘long term’ and “public good’. The distinction is thus established with the outsourcing of public services under the tender modality to the private sector with short to medium-term contracts, and do not provide permanent public services. Cleaning and washing services outsourced to private parties by public hospitals or health services, in consequence, are not social concessions.

Hospital concessions typology

The following typology is proposed in order to understand the formats adopted by hospital concessions in different parts of the world, allowing for certain conceptual stylizations. The main features are as follows:

- The public sector issues contracts to private organizations for the provision of healthcare and operations services financed by the public treasury, within a public facility: for instance, purchasing services in hospitals to shorten surgery waiting lists.

- The public sector contracts a private party to finance, design, build and operate a hospital that is within the public network.

- The private sector builds and expands the hospital’s capacity and sells its services to the public funder. In some cases, a tender is held for procurement from the private sector. In others, there is a tender for private parties to take responsibility for existing public facilities.

- The public sector leases a plot of land for use by the private party, in exchange for the provision of services.

In Chile, the main distinction made is whether to include clinical care services within the arrangement.

Reasons for introducing a health concessions policy

The reasons behind why some governments have decided to push forward with a policy on social health concessions are mainly two: pragmatic and ideological/utopian. The pragmatic reasons have arisen due to the need to bridge gaps in hospital investment in a short time, the sectoral budget being unable to cover all of the identified needs. Moreover, governments that have fiscal rules on debt may be well disposed toward the fact that funding for hospital construction is for accounting purposes itemized as private –and not public– debt. In these cases, fiscal payment for the contract with the private party is extended for the entire duration of the contract (15 to 30 years), thereby minimizing the fiscal impact. Another pragmatic benefit lies in the fact that, granted the infrastructure expansion policy can start immediately, payments will be made over several years afterward, extending to subsequent governments.

The ideological/utopian reasons fall under what has been described in the literature on concessions as New Public Management [4] or rather, those who believe that private parties are better at management and efficiency, and therefore need to be incorporated with the main purpose of improving hospital services. This school of thought has also prevailed in Chile, where it is known as the neoliberal logic.

In short, it can be said that the rationale behind introducing hospital concessions takes into account ideas such as the following [5]:

- It could bridge the health infrastructure gap more quickly

- There would be no fiscal debt

- The risk would be passed-on to the private parties

- Private sector management expertise is introduced

- Capitalizes on the supposedly greater efficiency of the private sector in the use and administration of resources

- Payment for the obtained infrastructure is passed-on to future governments

- The market is freed up to full value creating potential

- Resources are made available for the State to invest in social policy

- The public procurement system (the public regime), which slows and complicates the refitting of hospital equipment, can be sidestepped entirely

- The State principle of subsidiarity remains intact

Critical analysis of health concessions

Have public-private partnerships passed the test of time? The international literature reveals little –and yet much– for the analysis of this policy. Little, because of the too few studies assessing the expected outcomes of applying hospital concessions over time. Much, because several studies are appearing and that attempt to create conceptual frameworks in order to better understand the historical and practical process of the implementation of this policy, employing a more critical approach.

1. Gap-bridging argument

The country with the most experience in hospital concessions is the United Kingdom. Studies performed there –with the longest track record in terms of the policy outcomes– indicate that, contrary to what was expected, the total health capacity did not increase after 10 years of building hospitals through the Private Finance Initiative. In fact, it declined [6], [7].

2. No-fiscal-debt argument

Also here the aforementioned United Kingdom case can serve as a model to demonstrate that once the hospital concession plan is effectively underway (with more than 100 concession hospitals in operation), the fiscal effect is devastating. If previously the health services provided under the National Health Service was spending around 6% of their annual budget in infrastructure, with the concession hospitals this amount increased to more than double in most cases, and in some cases even as much as 18.6% of the annual budget [8]. This has meant a great burden of debt which translates into a negative externality for the population, since health services had to make cuts in services to be able to pay the installments due to the concessionaires. The Private Finance Initiative has reached such a high level of burden that it is now being seriously put into question, and this policy is not expected to have a place in the UK in the immediate future [9].

Granted accounting-wise the expense cannot initially be itemized as public debt, ultimately it will be, given that the service will have to pay an annuity for construction and for providing services that will inevitably come out of the current budget, once the concession hospital becomes operational.

One of the more delicate aspects to take into account in this matter is the deferred transfer of payments to future generations, who had no say in the definition of public-private partnerships [10]. In the United Kingdom, many are now questioning whether intergenerational equity has been put in jeopardy as a consequence of the Private Finance Initiative.

3. Transfer of risk to private parties argument

This is one of the fallacies in the arguments in favor of healthcare concessions. It ignores the depth of the problem created due to contracts that, all over the world, are essentially rigid, lacking the flexibility to introduce modifications that meet the dynamic shifts in demand for healthcare, or epidemiological changes that push healthcare services to adjust their service portfolio accordingly.

With regard to highway concessions it has also been seen that contractual inflexibility –which is necessary to make the investment attractive for private parties by offering certainty in the operational and legal framework– becomes a heavy burden when it comes to introducing structural modifications for whatever the reason [11],[12].

The health area is, by definition, changing and uncertain. The rigidities associated to the contracts increase the risk instead of decreasing it, since it is not possible to introduce modifications to the scale or modularity of healthcare infrastructure, nor changes to the hospital management models, nor adjustments in the services based on demand or layout of the healthcare network.

Nevertheless, the greatest risk falls entirely in the hands of the public treasury. This occurs when a concession venture fails: here the ‘Too Big to Fail’ precept comes into play, which became known in 2008 amidst the global financial crisis when private banks had to be bailed-out at taxpayers´ expense. When a public good is put into the hands of private parties, it cannot fail nor disappear, and the State will ultimately always be the guarantor of last resort. Also here, the supposed transfer of risk to the private party ends-up being a fallacy, or a utopian mirage originally painted as factual argument whereas in reality this was never the case.

4. Greater private sector efficiency argument

A recent systematic review on the literature regarding comparative performance between private and public health systems in low to medium-income countries showed there was no evidence lending weight to the affirmation that the private sector is overall more efficient, transparent, and more effective healthcare-wise than the public sector [13].

In the Social Determinants Commission’s final report [14], the World Health Organization recommends bolstering the role of the State in providing essential healthcare-related goods and services, mainly attending to the need for introducing equity policies in healthcare in all spheres of public action.

In general, there is no sound evidence to conclude that public sector management is more inefficient than management by its private counterpart. It is known, however, that management by the State in its public function should be subject to a public regime, which undoubtedly contains more controls and levels of accountability of those that operate in contracts among private parties, mainly with the purpose of ensuring the proper use of resources which are provided by the taxpayers and whose benefits are for the population as a whole. This is not the same as inefficiency.

5. Fiscal funds release argument

According to the logic of the subsidiary State, the ideologically accepted social expenditure is spending through socially targeted policies that aim to provide society with a minimum social security network for combating extreme and hard poverty. Therefore, a small-size State should spend only on poverty reduction, but not allocate funds for investment in public infrastructure or public works that could be performed by the private sector. Neoliberal thinking goes on to say that this is the way to ensure economic growth and job creation, which are the source of individual welfare.

The question might be posed as to whether this policy is effectively prudent from the viewpoint of macroeconomics as well as fiscal responsibility. The UK experience clearly shows that an overprice ranging between 1.49 and 2.04 times more is paid for each hospital concession included in a comparative study between the cost of providing a concession (Private Finance Initiative) vis-a-vis the State providing it directly through debt for its construction through the relevant sector budget.

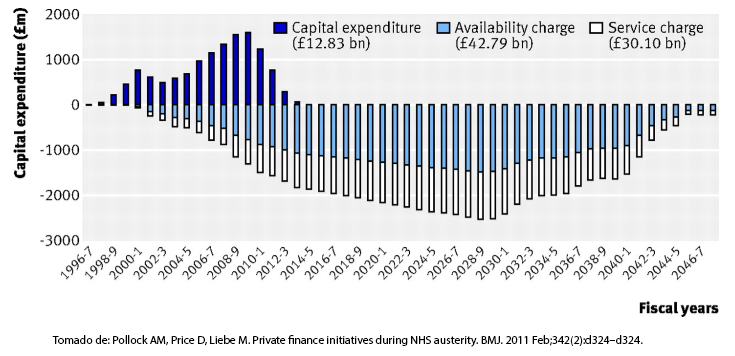

In the previous figure, Pollock et al. [8] show the capital expenditure for 150 hospital concessions up to 2009, and cash flow forecasts for construction, maintenance, and basic operation fees until extinction of these projects in approximately 2050.

Unlike the case of highway concessions ‒where the outsourced investment project is paid through cash flow ensured by the estimates for users’ travel and toll payments ‒ in the case of hospitals the payments are made by the healthcare services out of public budgeting.

The main question raised is then: What does the State gain by awarding to private parties ‒at a high overprice‒ the construction and operation of hospitals that it can itself build by means of debt through sovereign bonds? The case of the UK is conclusive as it fails to show evidence of a favorable cost-benefit relationship from the viewpoint of public sector interests [15], [16].

6. Improved quality of service argument

The UK case also offers evidence that 72% of hospital concessions had a bed occupation rate above the recommended upper limit. The Chilean case also constitutes a clear example of how misplaced incentives, like increasing occupation rates, which leads to a fine for the State in the case of prison concessions, entails a worse service and appalling results in terms of decent living conditions in prisons for convicts, their rehabilitation and subsequent reinsertion to society.

It is to be assumed that, if the same provisions that are applicable to prison concessions were to be applied to the concession contracts of the La Florida and Maipu hospitals, where the healthcare services ought to pay an extra charge when the bed occupation rate exceeds a certain limit, there would be every incentive for hospital concessions to reach maximum occupancy at any time of the year, with the corresponding increased expense for healthcare services.

Insofar as the health services budget is a permanent drain on cash to cover annual payments to concessionaires, these budget funds will be insufficient to cover the procurement of supplies or hiring the necessary number of professional hours to meet the real and changing health needs of the catchment population. The public health system debt will be a permanent issue. The quality of the healthcare service will be affected with cutbacks in services and professional care. This will have to occur in order to balance the budget.

Conclusions

The most widely documented cases of hospital building through public-private partnership by means of concession contracts do not provide evidence that this modality may have fulfilled the promise of higher quality of service, greater efficiency or speed, or reducing the fiscal burden or debt.

On the contrary, there is ample evidence indicating that quality of healthcare services has been impoverished as a result of the successive budget cuts incurred by the health authorities in charge of hospital concessions in order to meet annual payments from their budgets.

There is also evidence ‒academic as well as from the comptroller general offices of several countries (England, Canada) ‒ that no greater benefits are created from investment in health infrastructure through private parties. In other words, according to these estimations, this type of investment has not proven to offer more Value for Money.

Many studies have documented the inter-generational irresponsibility of building under the private concessions policy. The debt has to be taken-on by future generations of citizens who had no say in the decisions made by the previous generation on this matter. From the ethical viewpoint, one has to ask whether the country is prepared to mortgage its future fiscal and financial stability for the sake of a short-term vision that is functional to market interests.

Finally, it would seem the real reasons for entrusting the construction of public health hospitals to private concessions are ideological, not based upon empirical evidence or studies that would prove this option is better than others in terms of the general public interest.

Notes

Interests

VCB states having been a member of the citizens' movement "Salud Un derecho" ("Health, a right") from 2010 to 2012, and advocating in favor of the State as guarantor of people's social rights, among them, health.

Figure 1. Capital expenditures, availability charge and concession services to 150 hospitals. 1996-2009 and projection to 2046, UK

Figure 1. Capital expenditures, availability charge and concession services to 150 hospitals. 1996-2009 and projection to 2046, UK

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

CONTEXTO

La política de concesiones comenzó en Chile durante el gobierno de Ricardo Lagos, orientada exclusivamente a concesiones duras (carreteras). Con el tiempo, se amplió a las concesiones sociales como cárceles y hospitales. Durante el primer gobierno de Michelle Bachelet se licitó, por modalidad de concesión, la construcción de dos hospitales de tamaño mediano de Santiago. Durante el gobierno de Sebastián Piñera se licitaron otros tres hospitales más.

ANÁLISIS CRÍTICO

Este artículo analiza críticamente los fundamentos por los cuales se han introducido políticas de concesiones blandas en diferentes partes del mundo. Señalo que los argumentos aducidos obedecen a dos grandes orientaciones: razones pragmáticas y razones ideológico-utópicas. Refuto las supuestas justificaciones relacionadas con cierre de brecha, efecto sobre deuda fiscal, traspaso de riesgo a privados, mayor eficiencia de los privados, liberación de fondos y mejor calidad de salud.

CONCLUSIONES

La revisión de la literatura internacional no arroja evidencia a favor de las concesiones hospitalarias en los supuestos argumentales utilizados para impulsarlas. Por el contrario, cuando se ha aplicado la metodología Value for Money, se observa una disminución de capacidad del sistema sanitario y empeoramiento de la calidad de la prestación. En el artículo indico que existe un potencial impacto en la equidad intergeneracional con proyectos que se extienden por plazos prolongados propios de las concesiones en salud. Concluyo que, dado que no hay una base de evidencia fundamentada en la técnica a favor de esta política, las verdaderas razones para concesionar son de tipo ideológico y funcional a los intereses de mercado y no del interés general.

Author:

Vivienne C. Bachelet[1]

Author:

Vivienne C. Bachelet[1]

Affiliation:

[1] Editor in chief, Medwave

E-mail: vbachelet@medwave.cl

Author address:

[1] Villaseca 21, oficina 702,

Ñuñoa,

Santiago de Chile.

Citation: Bachelet VC. Hospital concessions in Chile: where we are and where we are heading. Medwave 2014 Nov;14(10):e6039 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2014.10.6039

Submission date: 23/9/2014

Acceptance date: 17/11/2014

Publication date: 25/11/2014

Comments (0)

We are pleased to have your comment on one of our articles. Your comment will be published as soon as it is posted. However, Medwave reserves the right to remove it later if the editors consider your comment to be: offensive in some sense, irrelevant, trivial, contains grammatical mistakes, contains political harangues, appears to be advertising, contains data from a particular person or suggests the need for changes in practice in terms of diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic interventions, if that evidence has not previously been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No comments on this article.

To comment please log in

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics.

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics. There may be a 48-hour delay for most recent metrics to be posted.

- Tapia HR. Concesiones en Salud, un modelo válido para la reconstrucción y transformación de la red hospitalaria en Chile. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2010 Jun;81(3). | Link |

- Bachelet VC. [Private financing in public health infrastructure: call for papers on national experiences]. Medwave. 2014 Jan;14(7):e6009 | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Montagu D, Harding A. A zebra or a painted horse? Are hospital PPPs infrastructure partnerships with stripes or a separate species? World Hosp Health Serv. 2012;48(2):15–9. | PubMed |

- Blanken A. Flexibility against efficiency? An international study on value for money in hospital concessions. [S.l.]: University of Twente, 2008.

- Bachelet VC. A critical review of three dimensions of private finance initiative in health: risk, quality and fiscal effects. Medwave. 2010 Oct;10(09):e4780. | CrossRef |

- Liebe M, Pollock A. The experience of the private finance initiative in the UK’s National Health Service. The Centre for International Public Health Policy, 2009 [on line]. | Link |

- Hellowell M, Pollock AM. The private financing of NHS hospitals: politics, policy and practice. Economic Affairs. 2009 Mar;29(1):13–9. | CrossRef |

- Pollock AM, Price D, Liebe M. Private finance initiatives during NHS austerity. BMJ. 2011 Feb;342(2):d324–d324. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Davies P. Hard times: is this the end of the road for the private finance initiative? BMJ. 2010 Jul;341:c3828. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Parker D. The Private Finance Initiative and Intergenerational Equity. The Intergenerational Foundation, 2012 [on line]. | Link |

- Baillie J. Is the jury still out on PFI contracts? Health Estate. 2012 Feb;66(2):41-5. | PubMed |

- Prosser K, Gates R. Maximising value from PFI contracts. Health Estate. 2012 May;66(5):59-61. | PubMed |

- Basu S, Andrews J, Kishore S, Panjabi R, Stuckler D. Comparative performance of private and public healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2012;9(6):e1001244. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008 | Link |

- Pollock AM, Price D. The private finance initiative: the gift that goes on taking. BMJ. 2010 Dec;341:c7175. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Squires M. The private finance initiative: a case study of wastage in the NHS in Wandsworth. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 Apr;62(597):208-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tapia HR. Concesiones en Salud, un modelo válido para la reconstrucción y transformación de la red hospitalaria en Chile. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2010 Jun;81(3). | Link |

Tapia HR. Concesiones en Salud, un modelo válido para la reconstrucción y transformación de la red hospitalaria en Chile. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2010 Jun;81(3). | Link | Bachelet VC. [Private financing in public health infrastructure: call for papers on national experiences]. Medwave. 2014 Jan;14(7):e6009 | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bachelet VC. [Private financing in public health infrastructure: call for papers on national experiences]. Medwave. 2014 Jan;14(7):e6009 | CrossRef | PubMed | Montagu D, Harding A. A zebra or a painted horse? Are hospital PPPs infrastructure partnerships with stripes or a separate species? World Hosp Health Serv. 2012;48(2):15–9. | PubMed |

Montagu D, Harding A. A zebra or a painted horse? Are hospital PPPs infrastructure partnerships with stripes or a separate species? World Hosp Health Serv. 2012;48(2):15–9. | PubMed | Blanken A. Flexibility against efficiency? An international study on value for money in hospital concessions. [S.l.]: University of Twente, 2008.

Blanken A. Flexibility against efficiency? An international study on value for money in hospital concessions. [S.l.]: University of Twente, 2008.  Bachelet VC. A critical review of three dimensions of private finance initiative in health: risk, quality and fiscal effects. Medwave. 2010 Oct;10(09):e4780. | CrossRef |

Bachelet VC. A critical review of three dimensions of private finance initiative in health: risk, quality and fiscal effects. Medwave. 2010 Oct;10(09):e4780. | CrossRef | Liebe M, Pollock A. The experience of the private finance initiative in the UK’s National Health Service. The Centre for International Public Health Policy, 2009 [on line]. | Link |

Liebe M, Pollock A. The experience of the private finance initiative in the UK’s National Health Service. The Centre for International Public Health Policy, 2009 [on line]. | Link | Hellowell M, Pollock AM. The private financing of NHS hospitals: politics, policy and practice. Economic Affairs. 2009 Mar;29(1):13–9. | CrossRef |

Hellowell M, Pollock AM. The private financing of NHS hospitals: politics, policy and practice. Economic Affairs. 2009 Mar;29(1):13–9. | CrossRef | Pollock AM, Price D, Liebe M. Private finance initiatives during NHS austerity. BMJ. 2011 Feb;342(2):d324–d324. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Pollock AM, Price D, Liebe M. Private finance initiatives during NHS austerity. BMJ. 2011 Feb;342(2):d324–d324. | CrossRef | PubMed | Davies P. Hard times: is this the end of the road for the private finance initiative? BMJ. 2010 Jul;341:c3828. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Davies P. Hard times: is this the end of the road for the private finance initiative? BMJ. 2010 Jul;341:c3828. | CrossRef | PubMed | Parker D. The Private Finance Initiative and Intergenerational Equity. The Intergenerational Foundation, 2012 [on line]. | Link |

Parker D. The Private Finance Initiative and Intergenerational Equity. The Intergenerational Foundation, 2012 [on line]. | Link | Prosser K, Gates R. Maximising value from PFI contracts. Health Estate. 2012 May;66(5):59-61. | PubMed |

Prosser K, Gates R. Maximising value from PFI contracts. Health Estate. 2012 May;66(5):59-61. | PubMed | Basu S, Andrews J, Kishore S, Panjabi R, Stuckler D. Comparative performance of private and public healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2012;9(6):e1001244. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Basu S, Andrews J, Kishore S, Panjabi R, Stuckler D. Comparative performance of private and public healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2012;9(6):e1001244. | CrossRef | PubMed | Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008 | Link |

Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008 | Link |Systematization of initiatives in sexual and reproductive health about good practices criteria in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in primary health care in Chile

Clinical, psychological, social, and family characterization of suicidal behavior in Chilean adolescents: a multiple correspondence analysis