Key Words: Violence, Obstetrics, Women, Midwifery, Parturition

Abstract

Introduction

Chile has an incipient policy regarding humanized birth practices. Obstetric violence is becoming an issue in the public discussion, as brought up by women. Despite this advancement, no initiatives were observed to overcome the conflict. Questions arise from the different points of view of the main stakeholders involved. These questions help identify strategies contributing to the development of health policies that consider influencing actors.

Objectives

To identify stakeholders' perceptions of humanized care in childbirth and obstetric violence.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review that included articles and analysis of texts reflecting the scientific communities' point of view. We included statements from governmental, social, professional, and political actors as expressed in institutional websites. Moreover, we performed a qualitative inductive, thematic content analysis.

Results

We included seventy documents. The scientific community is visualized as aligned with ministerial recommendations for personalized childbirth. Several researchers analyze the difficulties for its improvement due to the historical, socio-cultural, and economic construction of the predominantly biomedical model for birthing. Convergence is observed among the scientific community and other stakeholders in recognition of humanized birth benefits and the need to overcome institutional obstacles within the health sector. However, the progress of the proposed change is slow, and health professionals' resistance to address women's complaints towards obstetric violence and claim of quality care is observed. This discussion finds its reflection in a parliamentary discussion.

Conclusions

The stakeholders' analysis reflects areas of conflict and consensus, as well as the diverse interacting dimensions that hinder the advance of humanized care in childbirth. This broad analysis strategy contributes to identifying critical aspects to be addressed in the development of integral and effective health policies.

|

Main messages

|

Introduction

The autonomy of women in making decisions regarding their physical and mental health, including reproductive health, is supported by position statements from Helsinki[1] and Belmont[2] reports, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women[3], and the Fourth World Conference on Women[4]. Ethical aspects associated with human reproduction and women's health have been addressed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), the World Health Organization, and the International Confederation of Midwives[5],[6],[7]. Nevertheless, the approaches to adequate obstetric services have been numerous, including approaches that overlap, complement, and even oppose each other[8].

The biomedical approach, associated with medicated birthing, is focused on reducing maternal, fetal, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. This method depends on important 20th-century breakthroughs in maternal and infant health[9], such that it has become a paradigm rooted in the culture and the system of birthing services[10],[11]. In this approach, allopathic medicine, the health system, and health professionals are in control of patients and their illness-health processes, limiting their autonomy[12],[13],[14]. It has also failed to take into account certain aspects of quality, such as an integral approach, the consideration of user satisfaction, and the limitation of an unnecessary or harmful technological intervention[15]. In this context, the Chilean Ministry of Health published a Manual of Personalized Service in the Reproductive Process in 2008[16].

This tendency does not only come from healthcare actors. The feminist movement has coined the term "obstetric violence" when biological, psychological, and social needs are not considered, or when the autonomy of women is not respected in the delivery of reproductive services. The mistreatment of women and bodily interference without medical justification is understood as a form of gender violence. International networks have been established to observe this phenomenon, and in some Latin American countries, penalties are regulated[17],[18],[19],[20]. In Chile, the subject has arisen as an initiative of selected social organizations, backed by some deputies in parliament, but it has not received government backing, nor support from health professionals' organizations within the field of obstetrics.

To deal with the issues associated with obstetric violence and promote personalized birthing at the level of public policy, it is necessary to consider the actors involved (stakeholders), as they will ultimately contribute to it being rejected or coming into effect. By considering their perceptions and perspectives, differences and points of concurrence could be acknowledged. Currently, Chile has an incipient policy regarding personalized assistance of childbirth, and no policy regarding obstetric violence. Studies aimed to analyze the positioning of the stakeholders involved are also scarce. Therefore, this study aims to recognize and analyze the perceptions and opinions about obstetric violence and humanized birth practices of the actors involved in its care and management through two levels of document analysis: An analysis of primary and secondary studies conducted in Chile (scoping review with content analysis) and an analysis of stakeholders' statements. These findings will contribute to the generation of a legitimate policy on obstetric violence that contemplates all those involved.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review[21],[22], a systematic method with standards described by the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews published in 2018[22], based on a research protocol[1], that requires interdisciplinary or mixed methods perspective, and integration of heterogeneous information sources, study designs and other types of texts. Generally, scoping reviews do not include methodological quality assessment of studies included, since the results are not intended to solve clinical questions and recommendations, but to present an overview of the evidence on a topic. This review is based on Davis's and colleagues' scoping review definition[23]: "Scoping involves the synthesis and analysis of a wide range of research and non-research material to provide greater conceptual clarity about a specific topic or field of evidence (page 1386)."

The present review included two types of sources:

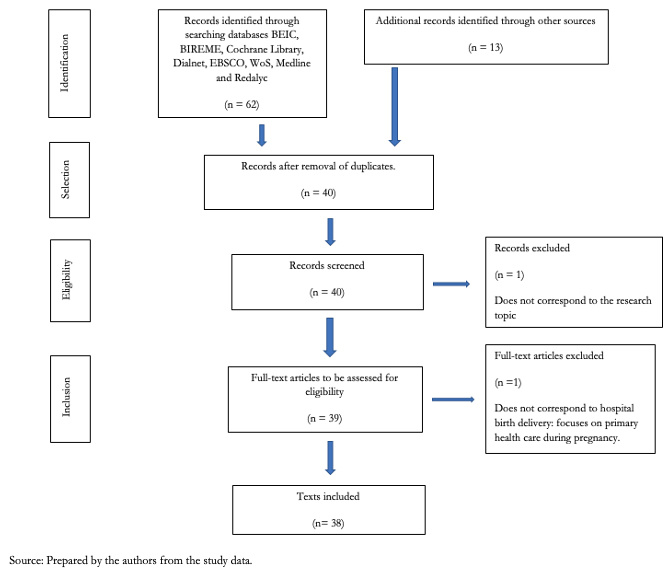

(a) Search of scientific articles, research reports, and analysis texts[20] to approach the scientific community's point of view (Annex 1). We performed a search of the studies conducted in Chile on obstetric violence and humanized birth practices in the following databases: BEIC, BIREME, Cochrane Library, Dialnet, EBSCO, WoS, Medline, and Redalyc. The following search terms were used in Spanish and English: obstetric violence, mistreatment, childbirth service, humanized, respected, and personalized childbirth. The problem of obstetric violence occurring in the context of abortion was not included. The search was complemented with the "chains" or "snowball" search technique[24],[25], where one source leads to another. All found studies and analysis texts were included, but for two studies that did not focused on birth delivery. Theses and Congresses' presentations were excluded, except for one study of academic trascendence in the field of study (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Selection sources of evidence.

The choice of works was guided by the following eligibility criteria:

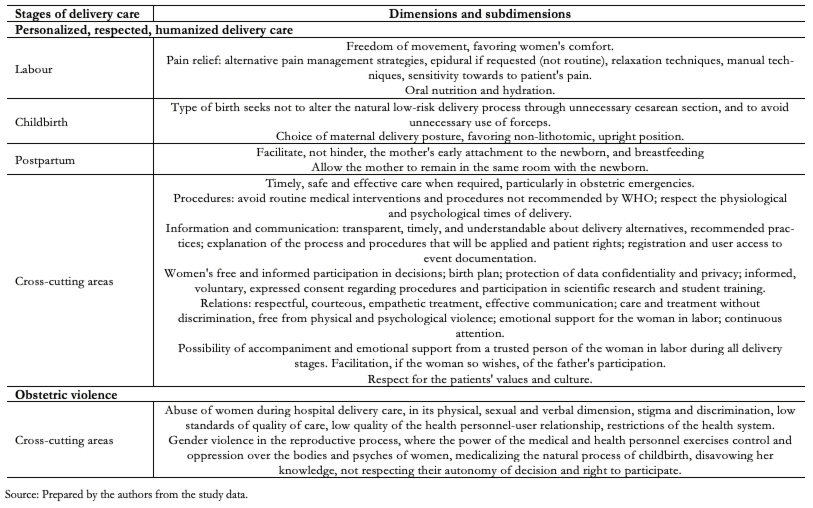

- Themes. The thematic eligibility criteria evolved considering two central dimensions, with their subdimensions: humanized, respected, personalized care of childbirth, and obstetric violence, mistreatment during childbirth[6],[16],[20],[26],[27],[28], as detailed in Table 1. It should be noted that, given the qualitative approach and inductive nature of the present review, works with other subtopics were also collected, insofar as they contributed to the objective of the study, such as, for example, the historical and cultural development of midwifery as a profession (Table 1).

- Kinds of work. Various types of scientific or analytical texts, with no disciplinary area restriction, were considered eligible: primary studies of diverse design, secondary studies, reviews (narrative, systematic, meta-analysis), books containing research results, or book chapters written by researchers with analysis based on their investigations.

- Formats. Scientific journal articles, research reports, books, and book chapters.

- Language. Texts in Spanish, English, Portuguese, French and German were eligible, according to the team's proficiency.

- Period and country. Studies developed in Chile were examined between the years 2000 and 2019.

- Exclusion criteria. Sub-dimensions did not incorporate health care in the event of an abortion. Although the concept of obstetric violence includes action during an abortion, this was not considered in this review, as the focus of the study is delivery care. Health care in the process of abortion is influenced by determinants additional to those of delivery care, related to the legal, cultural, social, institutional context. This broader scope exceeds the focus of the present investigation because of its greater complexity. Theses and congresses' presentations were excluded, except for one precursory anthropological thesis of national transcendence in the research field of humanized birth and obstetric violence.

Table 1. Dimensions and subdimensions of the study according to stages of delivery care.

(b) Revision of texts published on institutional websites for analysis of other stakeholder groups[29] (Annex 2): We aimed to cover statements from the government, social organizations, professional associations, and political stakeholders, that reflect their position on the issue of obstetric violence and humanized childbirth. Documents were selected according to qualitative significance concerning the topic and saturation criteria. With these criteria, we reviewed websites of government institutions, including departments of health, human rights, women's rights, and gender equality. We revised the websites of Chilean social activist groups that promote humanized childbirth; the National Midwifery Professional Association, the National Scientific Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the National Congress. Analysis of social networks and mass media was excluded as it exceeded the scope of the present work. The sole exception was the social network RELACAHUPAN, the Chilean branch of the Latin American and Caribbean Network for Humanized Childbirth, as this entity did not have an alternative site and was the first social organization in the field in Chile (2000).

Analysis of the information was performed through qualitative, inductive, thematic content analysis[25]. The coding process was conducted at two consecutive levels: Initially, the documents were analyzed, identifying descriptive characteristics of the documents, and main themes and sub-themes contained in each one. A second level was an integrated analysis of them, from which emerged a set of explanatory categories of analysis. The coding of the studies included was performed and discussed by four authors: two for qualitative studies and two for quantitative studies, based on their methodological competence. The coding of the stakeholders' statement positions was done by three authors with different professional profiles (obstetrics, social science).

Results

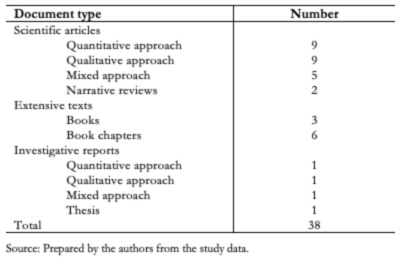

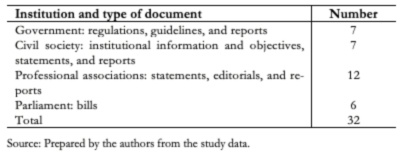

We included seventy documents published from 2000 to 2019: thirty-eight documents published by the scientific community in scientific journals, investigative reports, and extensive texts (Table 2, Annex 1), and thirty-two documents from professional, social, governmental, and political stakeholders, expressed on institutional websites (Table 3, Annex 2).

Table 2. Documents included the scientific community.

Table 3. Documents included other social actors.

1. Scientific community

As detailed in Annex 1, the studies were of diverse design, samples, and disciplinary approaches (i.e. health science, anthropology, sociology, and historiography). The majority were primary studies, although two were narrative reviews. Integrated content analysis of the documents revealed central categories approached by the scientific community: humanized care in childbirth, patient satisfaction, and historical-cultural construction of the predominant biomedical model.

1.1. Personalized birth

First milestones

During the 20th century, the first initiatives of reflection and participation in national and international activities around humanized birth came into effect, and studies regarding the quality of maternal services and cultural construction of childbirth care emerged. This happens in the context of an international movement: Chile joined a Latin American network for quality delivery and childbirth, leading to the development of a personalized birthing service in a maternity in Villarrica, southern Chile, in the year 2003[30],[31],[32].

Evaluation of experiences and advancements

Together with successful developments in other maternity institutions throughout the country[30],[31],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41], diverse studies that analyze the alignment of childbirth services with the new guidelines emerge. These evaluations reveal that while advances are perceived, unadvisable practices, elevated rates of caesarean sections and low incorporation of internationally recommended practices persist[10],[34],[37],[42],[43],[44].

User perception of the health service

The technical competence of health personnel is acknowledged. Nevertheless, user dissatisfaction is felt regarding their treatment over the course of care. Complaints occur more frequently in the public service and among young women with a low level of education[11],[33],[36],[37],[38],[43],[44],[45],[46],[47]. User dissatisfaction is primarily associated with impersonal attention, professional carelessness, lack of information, and lack of consideration of women’s choices[33],[36],[37],[38],[43],[44],[45],[46],[47]. There is fear to express any complaint, pain, or concern, and women think they will be assisted only if "they behave themselves." It is considered that attention has improved over time[37].

Studies focusing on maternal well-being consider the following dimensions: physical-corporal, cognitive, emotional, and environmental perception[33],[37],[44],[48]. Health service is considered of quality when it is opportune, effective, informed, accompanied, pleasant, respectful of women's needs, motivating mothers and facilitating their participation, and supportive for pain management. Contact with the newborn is highly valued[37],[48]. A clean, comfortable, and cozy physical environment is also important[33]. User preference for the private sector is associated with a perception of higher quality care and a personalized relationship with the gynecologist[33],[44].

The accompaniment on the part of the father, relatives, or significant others is highly valued. Its importance is identified in terms of emotional support, contention and the woman's sense of security[49],[50]. It is also associated with better obstetric results and the father's relationship with the newborn and the mother at postpartum. While accompaniment has increased[45],[47],[49],[50], barriers that persist are lack of infrastructure and insufficient empowerment of users to demand this right[11],[33], as well as cultural norms that stipulate little participation on the part of fathers in reproductive tasks[33],[49],[50]. A primary reason for paternal absence in prenatal controls, childbirth, or discharge from hospital is work responsibility[33],[49],[50]. Institutional barriers at hospitals are also mentioned, such as inadequate open hours for visitors, infrastructure, or limiting protocols[33],[38],[48],[49],[50],[51],[52]. Distance and access to hospital facilities may be an obstacle in rural areas[38],[48],[51],[52]. Fathers value their personal paternal experience and perceive their participation in supporting mothers as important[49],[50].

Weaknesses

Scarce information and lack of proactivity of health personnel, lack of empowerment of the midwifery team in management, and lack of user information are among barriers to a new model of service[47],[48],[53],[54],[55],[56],[57],[58], as are inadequate infrastructure and the insufficient staff[44],[45]. Nevertheless, proposals have been made to achieve progress[53],[55],[56].

High rate of cesarean section

The rate of cesareans in Chile is frequently mentioned and varies according to public or private health sectors[36],[59],[60],[61],[62]. A majority of obstetricians from the public sector also work in the private sector to supplement their income; this affects the organization of work in obstetric teams and results in programming of cesarean births[31],[34],[48],[54],[60]. Most women do not prefer cesarean delivery[38],[48],[59], however, it is easy to convince them, given the fear of childbirth[36],61],[62] that is reinforced by the mass media[36]. Medical authority is unlikely to be questioned and scarce information is available concerning non-surgical alternatives and potential risks of cesarean delivery. This has been reinforced by a reduction in public health coverage since the 1980s and a growing increase in benefits that facilitate access in the private sector[31],[48],[54],[60]. Proposals for articulated work between ministerial policies, universities, scientific research, services, health teams, and civil society have been made. The necessity to audit the quality of care, the need for transparent information, and strengthening of prenatal education are highlighted[47],[48],[53],[54],[55],[56],[57],[58].

1.2. Historic and cultural construction of the predominant model of birthing service

The vision of women, midwives and moving towards professional care in childbirth

Since the 18th and 19th centuries[63],[64], there has been a transition from home births, attended by traditional birth attendants, to professional midwife-deliveries under the observation of obstetric doctors. The collective vision at the time considered the feminine body and sexuality to be sinful, and painful birth allows for atonement. Whoever houses this body is considered weak and ignorant[62]. The woman is submitted to the medical authority in so far as traditional birth attendants continue to be relegated, disqualified as ignorant and immoral, and are judicially persecuted[64]. The scientific and technological advancements contribute to this tendency.

Establishment of the hegemony in childbirth care

In the second half of the 20th century, maternal mortality is a central public health concern and declines with the formation of the National Health Service (1952). A model is installed that reaffirms the "pathologization" of childbirth care and losing ancestral traditions[30],[31],[33],[34].

Mechanisms of hegemony and obstetric violence

Childbirth in Chile occurs in the context of Western medical science, where women enter a foreign space and submit themselves to the health authority, becoming a patient who must comply with hospital norms. Their knowledge, needs, and emotions are mostly not considered; communication is scarce and technical. The woman finds herself frightened, threatened, or made to feel guilty, unable to move, with difficulty resisting the intervention she is submitted to, and with her emotions and pain discredited[36],[37],[41].

Birth care in the present health care system as a social determinant of health

The predominant model of care in childbirth, in which not recommended practices persist, is rooted in a health system that is at the same time a social factor that acts as a barrier. This system represents paradigms, power relationships, and economic and organizational tensions, whose result is the interventionism above equity and the well-being of women[34],[53],[55],[56],[57].

2. Executive Power

Ministry of Health and Ministry of Social Development

In the context of the international commitments signed by the State of Chile and the health objectives of the country, the Ministry of Health produced and promoted a Personalized Care Manual for the Reproductive Process[16], with a focus on quality, integral care, and family medicine. It addresses psychosocial factors of the reproductive process, guidelines from birth control to postpartum care, support for breastfeeding, quality of care, and family guidelines for the development of informed consent for procedures during the reproductive process. Other documents refer to this manual; the first of those is the program to evaluate obstetric, gynecological and neonatological services[65], highlighting: timely delivery of information, psychological and emotional support for the pregnant woman, generation of comfortable space, minimum intervention and security throughout the birthing process. The second document is the General Technical Normative for Integral Postpartum Care[66], which provides clinical recommendations regarding monitoring, education, and provision of information to women, and evaluation of the care units. Regarding the management of pain postpartum, this document proposes patient controlled analgesia. The Guidelines for Gestation and Childbirth of the program "Chile Grows With You" ("Chile Crece Contigo")[67], guide prenatal care and provision of information about childbirth, making explicit the concept of humanized childbirth, types and positions of childbirth, and pain management options. Furthermore, they provide information about matters of mental health and sexuality during the gestation. The General Technical Normative for the Delivery of the Placenta[68], highlights the disposition and use of the placenta as cultural practice in Chilean society, establishing a regulatory framework for the autonomy of the woman in the decision for its handling.

The clinical practice guidelines for Analgesia in Childbirth[69] and the Perinatal Guidelines[70], correspond to a collection of technical guidelines regarding care over the reproductive process. These do not cite the Personalized Care Manual for the Reproductive Process[16] directly, although both reference certain aspects, such as the importance of the women's preference in pain management and favoring non-pharmacological practices.

The National Institute of Human Rights

The Institute dedicated a chapter to obstetric violence in their 2016 Annual Report[71], referring to the violation of human and obstetric rights, challenging working conditions for health professionals in providing care and gender violence stemming from the national cultural context. The document provides background information regarding international conventions and national regulations, criticizing the high rate of cesarean sections in Chile and the lack of implementation of personalized childbirth recommendations. It concludes with suggestions to the State of Chile to renew their commitment to the prevention, research, and eventual sanctioning of obstetric violence against women.

Ministry of the Woman and Gender Equity

No reference to obstetric violence or personalized childbirth was found on the institutional website of this Ministry.

3. Social actors

The following are civil society organizations that approach reproductive health from a perspective of patients' rights, and health and gender equity. These organizations form part of national and international networks, include health professionals and academics, and maintain alliances with universities, mass media and parliament members.

Observatory of Gender Equity

This organism has its roots within the context of a project of the Pan American Health Organization and includes the critical observation of sexual and reproductive health policies. This organization does not figure with an active website[72].

Latin American and Caribbean Network for the Humanization of Delivery and Childbirth, Chilean branch (RELACAHUPAN-Chile)

This is a network of organizations that proposes the improvement of the childbirth experience and delivery methods. It was formed following the "Humanization of Delivery and Childbirth" Congress in Ceara, Brazil (2000). The Chilean branch functions as a non-profit organization that promotes respected childbirth, delivers guidelines and orientation, carries out activities, and participates in the coordinating body for delivery and childbirth rights in Chile[73],[74].

Observatory of Obstetric Violence (OVO-Chile)

Starting in 2015, this is a multidisciplinary organization to make victims of obstetric violence visible, accompany them, and denounce traumatic experiences. It offers educational and preventive activities, fostering the dissemination of informative material. It also takes part in the above-mentioned coordinating body[75].

Miles Corporation

They published a document in 2016 concerning sexual and reproductive rights, that reports obstetric violence in Chile, its forms, laws and current policies on the subject. The text also refers to civil society's actions and challenges[76].

Coordinator for Childbirth Rights-Chile

This coordinating body is formed by organizations and individuals with the aim of promotion and activism for rights during pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum, and upbringing of children. They develop activities for denouncing obstetric violence and have articulated diverse organizations around the most recent law proposal (2018)[77].

4. Health professional associations

Chilean Association of Midwives

Since 2014, this association has published a variety of position statements in the media in response to public complaints about obstetric violence[78]. The association holds the State responsible, arguing that the conditions for dignified childbirth services have not been implemented. However, the debate is observed among members, exemplified by a public declaration of a group of professionals from different regions against the Association's official position[79]. Notwithstanding they agree with State responsibility, they propose additional action is required on the part of institutions and individuals, calling for reflection and change in care delivery. In 2017, following legal initiatives, the association expressed they will not protect mal praxis, but rejects the promotion of the concept of obstetric violence as instilling unnecessary fear in the population and bringing the profession into disrepute. They highlight gender violence is also practiced against the midwives, predominantly women, and criticized accompaniment by non-professionals ("doulas") and profiteering from humanized childbirth services by private clinics, generating inequity in the global health system[80].

A working group was put together in 2018 in which the Association participated, giving rise to a new legal initiative[81], pressuring the government to improve perinatal guidelines and return to the "Right of Women to a Life Without Violence" law. In 2019, the Santiago branch of the Association organized the first "Advancements in Respectful Maternal Care" seminar. It covered the necessity for the association to be up-to-date with material on the topic, maintain a discussion with women and citizens, boost measures to improve professional practice, and develop policies based on rights[74]. Recently, the Association displayed the motto "respected childbirth promoters" on its institutional website, presenting successful experiences in the country's north, evidencing a shift in its public discourse[83].

Chilean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology

A change in the delivery of care at childbirth is reflected in a 2013 publication in the society's scientific journal[84]. It puts forward a critique of a highly medicalized model. Nevertheless, before the publication of the Manual of Personalized Service in the Reproductive Process in 2008[16], an editorial suggested that incorporating personalized birth care within Explicit Health Guarantees in the current system, a law that ensures user access, currently not the case, would diminish freedom of doctor-patient choices in private practice[85]. It is also said that an underlying cultural aspect cannot be resolved by law. No further references to the ministerial proposal of incorporating personalized birth care in the Explicit Health Guarantees were found in the journal.

The Chilean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology held a scientific session in 2015 in which the matter of obstetric violence was discussed, welcoming the need to improve the quality of care, considering the mother's participation and satisfaction. Nonetheless, they did not agree with an obstetric violence law, claiming that such a law would question their professionalism and would have little impact on cesarean rates. They argue that the country already counts on a user rights law[86], that could be expanded in birthing service rights. They indicated that the obstetric violence proposal details penal actions, leading to the question of whether other health provisions will give rise to new sanctioning laws. The following proposals were made: a behavioral change requirement, adequate selection of at-risk patients, regulation for management with minimum intervention, delivery houses belonging to competent health institutions, audits to evaluate quality indicators, elimination of economic incentives for cesareans, improvement of equity in infrastructure and access to professionals, and continued training for personnel beyond solely clinical aspects[87]. In another editorial, the author wonders how to advance consensus in delivery modalities and integral childbirth to positively transform users' experience, rather than merely securing it. It highlights that the initial legislative proposal addressing obstetric violence arises from criticism and was met with resistance from professional stakeholders[88]. The empowerment of users reached a peak, without adequately trained personnel to meet the need. An invitation is made to construct knowledge around more integral pilot proposals, to validate new procedures, and work with the families. It calls on specialists to design intervention strategies for an experience of positive and shared childbirth.

5. Legislative Power

During the last decade, there has been a steady evolution in regulations related to health and gender rights. The 20 584 General Law of rights and duties of health care for the people was enacted in 2012. It considers security, dignified treatment, company, spiritual assistance, information, autonomy, and user participation[86]. Since 2015, various bills regarding obstetric violence have been presented without advancing in constitutional processes. A group of parliamentarians presented a bill that defines and identifies constitutive acts of obstetric violence, raises women's rights in the gestation process and childbirth, and proposes sanctions[89]. At the end of 2017, a new initiative was presented[90], in which the Coordinator for Birth Rights participated. It consisted of modifying the 20 584 General Law, typifying mistreatment, and including guarantees of women's rights during gestation, childbirth and postpartum. Towards the end of 2018, a more integral legal initiative began, developed through working groups in which a variety of actors took part together with the Coordinator for Birth Rights[81]. It intends to guarantee the rights of women, the newborn, the partner, and the family in the gestation, pre-birth, birth, postpartum, and three legal indications for abortion in Chile, and in gynecological and sexual health. The text provides context, defines recommended and non-recommended actions, mistreatment and sanctions. In April 2019, a draft law was introduced in the parliamentary chamber of deputies, but has not been discussed further: it modifies the Penal Code, typifying the crime of mistreatment concerning the pregnant woman, committed by health professionals[91]. Only the bill started in 2017 has progressed to date[83]. It stipulates duties of the State health care, including detection of violence against women and mechanisms of response in conjunction with other State bodies.

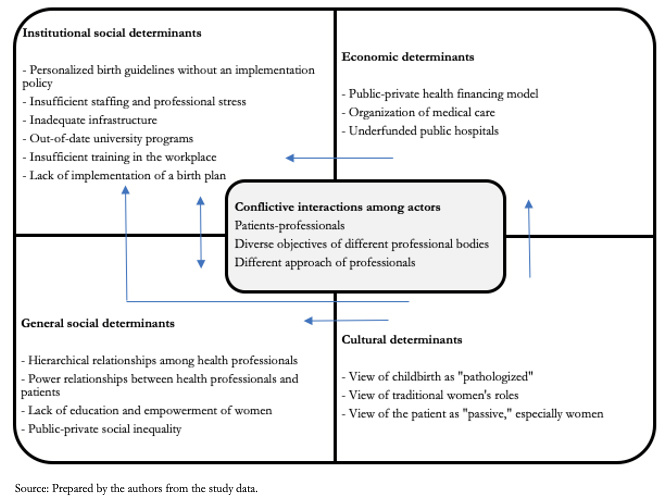

6. Interacting dimensions

Figure 2 presents the interacting dimensions resulting from the integrated analysis of published studies and position statements of actors, that explain conflictive interactions among involved stakeholders.

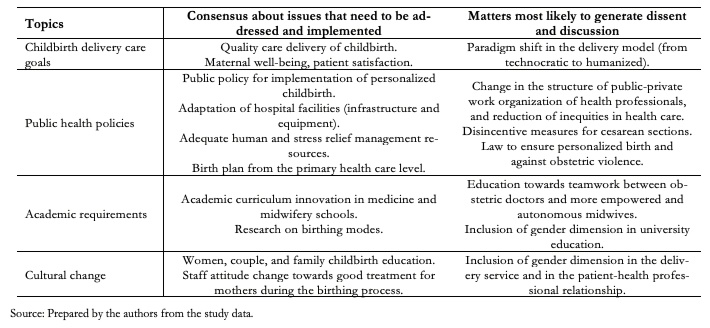

7. Areas of consensus and dissent

Analysis of the various documents reveals areas where consensus is more likely to be reached, and reveals aspects that most likely would raise dissent discussion among the diverse stakeholders, as presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Consensus and conflicting areas.

Discussion

Analysis of studies conducted by the scientific community in Chile exhibits a perspective related to the international orientations regarding childbirth care[6]. In effect, the modalities of care guided by these achieve better obstetric results and user satisfaction. Studies are generally observational and descriptive of experiences framed in a conception of humanized childbirth or present successful experiences of change. Few perform analytical evaluations. No research evaluating traditional practices or possible benefits of caesareans was found. The need to keep reporting different experiences is envisaged, as well as the evaluation of diverse clinical practices at a national scale.

The interdisciplinary nature of the studies brings attention to a more integral understanding of the difficulty to improve humanized childbirth and the persistence of obstetric violence in the country. Analysis of Ministerial documents exhibits an effort by the State to improve the quality of childbirth care. Notwithstanding, many orientations are technical, leaving implementation at the disposition of health care institutions. Considering differences in physical and human resources among different maternity services throughout the country, the homogenization of care remains a complicated institutional challenge.

The analysis of different stakeholders' perceptions, shows divergences between health teams and users, among health professionals that ascribe to different paradigms of care, and among political actors of diverse ideological tendencies. A distancing between social organizations, professional associations, and state policies is observed. This tendency has been verified in a recent media analysis in five Latin American countries, regarding discursive positions of different actors facing obstetric violence, pregnancy, and childbirth care[8].

The interaction of the identified factors displays significant disagreement between stakeholders, the principal being the perception of obstetric violence, and the laws proposed to sanction it. It is envisaged, by those that propose it, not as a medical issue but as violence against women, founded in the asymmetric relationship of gender[41]. The accusation of obstetric violence is expressed in the context of the feminist movement and therefore goes beyond criticism of any other provision of medical care that may be lacking in quality. This is worsened by the transcendence of birth as a life event and the vulnerability of the woman during this process. Facing the lack of advancement perceived, legal initiatives arise as an option to protect women. On the other hand, for health professionals care in childbirth is a medical act, a specialty like any other. The complaint is offensive to them and seen as criminalization of their professional practice. The Ministry of Woman and Gender Equity does not approach the matter, suggesting that care in childbirth is considered a medical act by society. The need for a more intimate dialogue is envisaged for mutual understanding and integration of both views.

Other areas of complexity occur at a structural level. The hierarchical nature of the relationships between health personnel and health system users, especially in the public system. In this context, the rights and autonomy of "patients" are weakened, being their duty to "recover" and return to society[41]. The economic factor, consisting of the financing scheme of the public health system, is also relevant. Its modification, besides requiring a greater injection of resources from the State, could affect private interests.

Despite the stated difficulties, the possibility of areas of consensus and alliance also emerges from these findings. These mainly relate to the improvement of childbirth care, the search for user satisfaction, and the need for the public sector to generate conditions to advance towards effective implementation of the new model. Following the discussions of laws for respected childbirth and sanctions for obstetric violence, the Chilean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology proposes taking on the problem and developing improvement measures[88]. Although the Midwives Association has not expressed self-criticism regarding care, personalized birth has been added to its list of public priorities[83].

From the analysis of the determinants of the current childbirth care model, and the consensus and dissent of actors around it, the need of advancing in a humanized birth policy and financed action plan, can be deduced. The plan should be multiannual, with gradual goals, starting with the most viable areas and issues that elicit more consensus. However, the plan should also consider the analysis of the conflicting ones. The policy should be multidimensional[26], therefore intersectoral (health, education, public works, social development, women and gender equity, science, youth) to cover the various determinants and complexity of the problem. And it should be developed and evaluated by the stakeholders involved, as stated by the World Health Organization[93]: public and private institutions, health professional associations and scientific societies, universities as an instance of academic training and research, civil society and parliament, and above all, by mothers and fathers as users of the health system.

A limitation of the present study has been the inability to approach private stakeholders and analysis of mass-media. Although the present review refers to them in some reviewed documents, a systematic study of these sources would be of interest. As a second limitation, we approached the perception of women, understood as a central stakeholder, through studies that included qualitative and quantitative research methods to investigate patient o health system users' satisfaction, and through civil society organizations concerned with women's rights, humanized birth and obstetric violence. However, to get a more comprehensive view of their perception, further sources could be analyzed, such as testimonies in social media or hospital claim offices. Also in this area, further primary and secondary studies are envisaged as of interest.

Despite the heterogeneity of the included resources in the present review, their different nature leads to more complex and comprehensive conclusions.

Conclusions

Given the complexity of obstetric violence and reproductive health care services, its improvement requires a strategic approach, which considers the different dimensions of the problem and advances with the maximum participation of stakeholders involved. From the analysis of the determinants of the current childbirth care model, and the consensus and dissent of actors around it, the need of advancing in a multidimensional humanized birth policy and a financed, multiannual, and participative action plan, can be deduced. Although specific experiences will probably continue to develop, the absence of a strategic approach will likely result in an increased breach of equality in the health care of women, and further conflict will likely arise, especially in the context of unmet expectations regarding the health system. The hypothesis that emerges from the present analysis appears to be supported by current events in Chile[94],[95], exhibiting generalized social dissatisfaction, in which demands to improve the health system and services and gender violence arise as important and independent aspects.

The results of this research show the existing obstacles to the application of the official guidelines in the context of social demand for humanized care in birth. The review involved a search from a variety of information sources and material (studies, other texts). This approach contributes towards a broader understanding and identifies aspects worthy to be approached by public policies to advance towards comprehensive and feasible recommendations in the light of women's values and preferences.

Notes

Authorship contributions

AS, FP: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing (original draft preparation, review and editing), supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

YM, VH, JS, MA, CP, LS, MC: Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing (original draft preparation, review and editing).

Competing interests

The authors have completed the ICMJE conflict of interest declaration form and declare that they have not received funding for the completion of this report; have had no financial relationships in the last three years with organizations that might have an interest in the published article; and have no other relationships or activities that could influence the published article. Forms can be requested by contacting the corresponding author or the editorial board of the Journal.

Funding

This work was supported by the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (CONICYT), Ministerio de Educación de Chile, Fondo Nacional de Investigación en Salud FONIS, under Grant SA15I20070.

Ethics

The study was evaluated by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidad de Valparaíso. Since the study's information source is secondary, accessed in public web sites, the committee dispensed the study from its ethical approval.

Figure 1. Selection sources of evidence.

Figure 1. Selection sources of evidence.

Table 1. Dimensions and subdimensions of the study according to stages of delivery care.

Table 1. Dimensions and subdimensions of the study according to stages of delivery care.

Table 2. Documents included the scientific community.

Table 2. Documents included the scientific community.

Table 3. Documents included other social actors.

Table 3. Documents included other social actors.

Figure 2. Interaction of explanatory dimensions resulting from the integrated analysis for the scientific discourse and other actors.

Figure 2. Interaction of explanatory dimensions resulting from the integrated analysis for the scientific discourse and other actors.

Table 4. Consensus and conflicting areas.

Table 4. Consensus and conflicting areas.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Introduction

Chile has an incipient policy regarding humanized birth practices. Obstetric violence is becoming an issue in the public discussion, as brought up by women. Despite this advancement, no initiatives were observed to overcome the conflict. Questions arise from the different points of view of the main stakeholders involved. These questions help identify strategies contributing to the development of health policies that consider influencing actors.

Objectives

To identify stakeholders' perceptions of humanized care in childbirth and obstetric violence.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review that included articles and analysis of texts reflecting the scientific communities' point of view. We included statements from governmental, social, professional, and political actors as expressed in institutional websites. Moreover, we performed a qualitative inductive, thematic content analysis.

Results

We included seventy documents. The scientific community is visualized as aligned with ministerial recommendations for personalized childbirth. Several researchers analyze the difficulties for its improvement due to the historical, socio-cultural, and economic construction of the predominantly biomedical model for birthing. Convergence is observed among the scientific community and other stakeholders in recognition of humanized birth benefits and the need to overcome institutional obstacles within the health sector. However, the progress of the proposed change is slow, and health professionals' resistance to address women's complaints towards obstetric violence and claim of quality care is observed. This discussion finds its reflection in a parliamentary discussion.

Conclusions

The stakeholders' analysis reflects areas of conflict and consensus, as well as the diverse interacting dimensions that hinder the advance of humanized care in childbirth. This broad analysis strategy contributes to identifying critical aspects to be addressed in the development of integral and effective health policies.

Authors:

Anamaría Silva [1], Francisco Pantoja[2], Yoselyn Millón[3], Verónica Hidalgo[4], Jana Stojanova[5], Marcelo Arancibia[5], Cristian Papuzinski[5], Luna Sánchez [6], Michelle Campos [2]

Authors:

Anamaría Silva [1], Francisco Pantoja[2], Yoselyn Millón[3], Verónica Hidalgo[4], Jana Stojanova[5], Marcelo Arancibia[5], Cristian Papuzinski[5], Luna Sánchez [6], Michelle Campos [2]

Affiliation:

[1] Centro Interdisciplinario de Estudios en Salud (CIESAL), School of Obstetrics, Faculty of Medicine, San Felipe Campus, Universidad de Valparaíso, San Felipe, Chile

[2] School of Obstetrics, Faculty of Medicine, San Felipe Campus, Universidad de Valparaíso, San Felipe, Chile

[3] Faculty of Medicine Library, Faculty of Medicine, San Felipe Campus, Universidad de Valparaíso, San Felipe, Chile

[4] Faculty of Medicine Library, Faculty of Medicine, Reñaca Campus, Universidad de Valparaíso, Viña del Mar, Chile

[5] Centro Interdisciplinario de Estudios en Salud (CIESAL), School of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Reñaca Campus, Universidad de Valparaíso, Viña del Mar, Chile

[6] School of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Reñaca Campus, Universidad de Valparaíso, Viña del Mar, Chile

E-mail: marcelo.arancibiame@uv.cl

Author address:

[1] Angamos 655, Edificio R2, Oficina 1107,

Reñaca, Viña del Mar, Chile

Citation: Silva A, Pantoja F, Millón Y, Hidalgo V, Stojanova J, Arancibia M, et al. Stakeholders' perceptions of humanized birth practices and obstetric violence in Chile: A scoping review. Medwave 2020;20(9):e8047 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2020.09.8047

Submission date: 10/6/2020

Acceptance date: 31/8/2020

Publication date: 21/10/2020

Origin: Not commissioned.

Type of review: Externally peer-reviewed by three reviewers, double-blind.

Comments (0)

We are pleased to have your comment on one of our articles. Your comment will be published as soon as it is posted. However, Medwave reserves the right to remove it later if the editors consider your comment to be: offensive in some sense, irrelevant, trivial, contains grammatical mistakes, contains political harangues, appears to be advertising, contains data from a particular person or suggests the need for changes in practice in terms of diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic interventions, if that evidence has not previously been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No comments on this article.

To comment please log in

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics.

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics. There may be a 48-hour delay for most recent metrics to be posted.

- The World Medical Association. Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM. Principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas en seres humanos. 1964. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The Belmont Report. Estados Unidos de Norteamérica: Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. 1979. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- ACNUDH. Convención sobre la eliminación de todas las formas de discriminación contra la mujer. 1979. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- ONU Mujeres. Declaración y Plataforma de Acción de Beijing. Declaración política y documentos resultados de Beijing+5. Naciones Unidas. Naciones Unidas. 1995. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Recomendaciones de la OMS para la conducción del trabajo de parto. OMS. 2015. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Recomendaciones de la OMS para los cuidados durante el parto, para una experiencia de parto positiva. Transformar la atención a mujeres y neonatos para mejorar su salud y bienestar. 2018. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Midwives IC of. ICM Definitions. ICM. accessed 24 July 2020). [Internet] | Link |

- Perdomo-Rubio A, Martínez-Silva PA, Lafaurie-Villamil MM, et al. Discourses on obstetric violence in the latin america newspaper: changes and continuities in the field of health care. Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública 2019; 37: 125–135.

- Vera C, Donoso E. Desaceleración en la reducción de la mortalidad materna en Chile impide alcanzar el 5° objetivo de desarrollo del milenio. 2019; 43: 13–20.

- Binfa L, Pantoja L, Ortiz J, et al. Assessment of the implementation of the model of integrated and humanised midwifery health services in Santiago, Chile. Midwifery 2013; 29: 1151–1157. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Sadler M. Así me nacieron a mi hija. Aportes antropológicos para el análisis de la atención biomédica del parto hospitalario. Universidad de Chile. 2003. [Internet] | Link |

- Menéndez EL. Modelo Médico Hegemónico: Reproducción técnica y cultural. Natura Medicatrix: Revista médica para el estudio y difusión de las medicinas alternativas. 1998; 17–22.

- Castro R. Génesis y práctica del habitus médico autoritario en México. Revista mexicana de sociología 2014; 76: 167–197.

- Foucault M. El nacimiento de la clínica: una arqueología de la mirada médica. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 2011.

- Sandall J, Hatem M, Devane D, et al. Discussions of findings from a Cochrane review of midwife-led versus other models of care for childbearing women: continuity, normality and safety. Midwifery 2009; 25: 8–13. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Ministerio de Salud Chile. Manual de atención personalizada en el proceso reproductivo. Santiago de Chile. 2008. [Internet] | Link |

- Belli LF. La violencia obstétrica: otra forma de violación a los derechos humanos. 2013. (accessed 30 August 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Benitez G. Violencia obstétrica. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina 2008; 31: 5–6.

- Gobierno de México. Senado aprueba sancionar violencia obstétrica. 2014. (accessed 30 August 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Williams CR, Jerez C, Klein K, et al. Obstetric violence: a Latin American legal response to mistreatment during childbirth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2018; 125: 1208–1211. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13: 141–146. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2009; 46: 1386–1400. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Hernández Sampieri R, Fernández Collado C, Baptista Lucio P, et al. Metodología de la investigación. 6 ed. México, D.F.: McGraw-Hill Education, 2012.

- Flick U. El diseño de investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata. 2015. (accessed 4 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Sadler M, Santos MJDS, Ruiz-Berdún D, et al. Moving beyond disrespect and abuse: addressing the structural dimensions of obstetric violence. Reprod Health Matters. 2016 May;24(47):47-55. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLOS Medicine 2015; 12: e1001847. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Arguedas Ramírez G. La violencia obstétrica: propuesta conceptual a partir de la experiencia costarricense. Cuadernos Inter cambio sobre Centroamérica y el Caribe; 11. 2014. (accessed 21 July 2020). [Internet] | Link |

- Van Dijk TA. Estructuras y funciones del discurso. Siglo XXI. 2005. (accessed 4 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Cisterna I. Una experiencia en Villarrica. In: Evolución de la Matronería en Chile Hitos y Desafíos. Santiago de Chile, pp. 109–113.

- Leiva G. Desarrollo del rol profesional en los procesos de humanización de la atención del parto. In: Evolución de la Matronería en Chile Hitos y Desafíos. Santiago de Chile, pp. 95–107.

- Leiva Rojas G, Sadler M. Nacer en Chile del siglo XXI: el sistema de salud como un determinante social crítico en la atención del nacimiento. Chile: Universidad del Desarrollo. 2016. [Internet] | Link |

- Leighton Naranjo A, Monsalve Treskow D, Ibacache Burgos J. Nacer en Chiloé: articulación de conocimientos para la atención del proceso reproductivo. Cuad méd-soc (Santiago de Chile) 2008; 174–191.

- Leiva Rojas G, Sadler M. Nacer en el Chile del Siglo XXI: el sistema de salud como un determinante social crítico en la atención del nacimiento. In: Vulnerabilidad social y su efecto en salud en Chile: Desde la comprensión del fenómeno hacia la implementación de soluciones, pp. 61–77.

- Sadler M. Revisión del parto personalizado. Herramientas y experiencias en Chile. Santiago de Chile. 2009. (accessed 26 January 2018). [Internet] | Link |

- Sadler M, Carimoney A. Cuerpos vividos en el nacimiento: del cuerpo muerto de miedo al cuerpo gozoso. In: Rastros y gestos de las emociones, desbordes disciplinarios. 2018.

- Sadler M, Leiva Rojas G, Bussenius P, et al. OVO Chile 2018, Resultados Primera Encuesta sobre el Nacimiento en Chile. June 2018. | CrossRef |

- Sadler M, Leiva Rojas G, Perelló A, et al. Preferencia por vía de parto y razones de la operación cesárea en mujeres de la Región Metropolitana de Chile. Revista del Instituto de Salud Pública de Chile 2018; 2: 22–29.

- Soto L C, Teuber L H, Cabrera F C, et al. Educación prenatal y su relación con el tipo de parto: Una vía hacia el parto natural. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2006; 71: 98–103.

- Uribe Torres C, Poupin Berttoni L, González Plaza R, et al. Protagonismo de la embarazada durante su trabajo de parto: efecto sobre los resultados maternos perinatales. Rev chil obstet ginecol 2000; 65: 371–7.

- Sadler M. Así me nacieron a mi hija. Aportes antropológicos para el análisis de la atención biomédica del parto hospitalario. In: Nacer, educar, sanar : miradas desde la antropología del género. Santiago de Chile, 2004.

- Cabrera J, Cruz B G, Cabrera F C, et al. Características del peso, edad gestacional y tipo de parto de recién nacidos en el sistema público y privado. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2006; 71: 92–97.

- Contreras Y, Olavarria S, Pérez M, et al. Prácticas en la atención del parto de bajo riesgo en hospitales del sur de Chile. Ginecol Obstet Mex 2007; 75: 24–30.

- Binfa L, Pantoja L, Ortiz J, et al. Assessment of the implementation of the model of integrated and humanised midwifery health services in Santiago, Chile. Midwifery. 2013 Oct;29(10):1151-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Binfa L, Pantoja L, Ortiz J, et al. Assessment of the implementation of the model of integrated and humanised midwifery health services in Chile. Midwifery 2016; 35: 53–61. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Binfa L, Pantoja L, Ortiz J, et al. Midwifery practice and maternity services: A multisite descriptive study in Latin America and the Caribbean. Midwifery 2016; 40: 218–225. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Valdés C, Palavecino N, Pantoja L, et al. Satisfacción de la mujer respecto al rol de la matrona/matrón en la atención del parto, en el contexto del modelo de atención personalizada en Chile. Matronas profesión 2016; 17: 62–69.

- Murray SF. Relation between private health insurance and high rates of caesarean section in Chile: qualitative and quantitative study. BMJ 2000; 321: 1501–1505. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Aguayo F, Correa P, Cristi P. Encuesta IMAGES Chile resultados de la encuesta internacional de masculinidades y equidad de género. 2011.

- Aguayo F, Correa P, Kimelman E. Estudio sobre la participación de los padres en el sistema público de salud de Chile. Santiago de Chile: Ministerio de Salud Chile, Chile Crece Contigo.

- Latorre R, Carrillo T J, Yamamoto C M, et al. Gobierno del parto en el Hospital Padre Hurtado: Un modelo para contener la tasa de césarea y prevenir la Encefalopatía Hipóxico-Isquémica. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2006; 71: 196–200.

- Salinas PH, Carmona GS, Albornoz VJ, et al. ¿Se puede reducir el índice de cesárea? Experiencia del Hospital Clínico de la Universidad de Chile. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2004; 69: 8–13.

- Bravo VP, Uribe TC, Contreras MA. El cuidado percibido durante el proceso de parto: una mirada desde las madres. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2008; 73: 179–184.

- Murray SF, Elston MA. The promotion of private health insurance and its implications for the social organisation of healthcare: a case study of private sector obstetric practice in Chile. Sociology of Health & Illness 2005; 27: 701–721. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Uribe C, Rivera MS, Contreras A, et al. Significado del bienestar materno en la experiencia de parto. 2006; 12.

- Uribe T C, Contreras M A, Villarroel D L. Adaptación y validación de la escala de bienestar materno en situación de parto: segunda versión para escenarios de asistencia integral. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2014; 79: 154–160.

- Uribe T C, Contreras M A, Villarroel D L, et al. Bienestar materno durante el proceso de parto: Desarrollo y aplicación de una escala de medición. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2008; 73: 4–10.

- Valenzuela Mujica MT, Uribe Torres C, Contreras Mejías A. Modalidad integral de atención de parto y su relación con el bienestar materno. Index de Enfermería 2011; 20: 243–247.

- Angeja A, Washington A, Vargas J, et al. Chilean women's preferences regarding mode of delivery: which do they prefer and why? BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2006; 113: 1253–1258. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Bonilla H. Cesárea a pedido. In: Evolución de la Matronería en Chile Hitos y Desafíos. Santiago de Chile, pp. 115–121.

- Sadler M, Rivera M. El temor al parto: Yo no me imagino el parto ideal, yo me imagino el peor de los partos. Revista Contenido Cultura y Ciencias Sociales 2015; 6: 60–73.

- Sadler Spencer M. Etnografías del Control del Nacimiento en el Chile Contemporáneo. Revista Chilena de Antropología. 2016:3. | CrossRef |

- Zamorano Varea P, Araya Espinoza A, Guerra Araya N (eds). Vencer la cárcel del seno materno: nacimiento y vida en el Chile del siglo XVIII. Santiago: Universidad de Chile, 2011.

- Zarate MS. Dar a luz en Chile, siglo XIX: De la ‘ciencia de hembra’ a la ciencia obstétrica. Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado. 2008. (accessed 14 November 2018). | CrossRef |

- Ministerio de Salud Chile. Programa para evaluar servicios de obstetricia, ginecología y neonatología. 2013. [Internet] | Link |

- Ministerio de Salud Chile. Norma general técnica para la atención integral en el puerperio. Santiago: MINSAL. 2015. (accessed 16 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Ministerio de Salud Chile. Atención personalizada del nacimiento | Chile Crece Contigo. 2016. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Ministerio de Salud Chile. Norma general técnica para la entrega de placenta 2017. 2017. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Ministerio de Salud Chile. Guía clínica analgesia del parto. 2013. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Ministerio de Salud Chile. Guía perinatal 2015. 1 ed. Santiago de Chile. 2015. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos. Informe anual 2016: situación de los derechos humanos en Chile. Chile: Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos. 2016. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Calvin, Maria Eugenia, Matamala, Maria Isabel, Eguiguren, Pamela, et al. Violencia Obstétrica. In: Informe Monográfico 2007-2012 . Violencia de género en Chile. Santiago de Chile: Organización Panamericana de la Salud, pp. 64–70.

- Relacahupan Chile. Relacahupan Chile. (accessed 17 October 2019). [internet] | Link |

- Vera López G. Relacahupan- 10 años de trabajo, desafíos y logros. Tempus Actas de Saúde Coletiva 2010; 4: 233–236.

- Observatorio de Violencia Obstétrica Chile. OVO Chile. 2015. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Infante G, Leiva G. Violencia obstétrica. In: Primer informe salud sexual salud reproductiva y derechos humanos En Chile. Estado de la situación 2016. Miles Chile, pp. 139–145.

- Coordinadora por los Derechos del Nacimiento - Chile. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Campos P. Colegio de Matronas: “La violencia obstétrica existe, pero la ejerce el Estado” « Diario y Radio U Chile. 2014. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Grupo Matrones y Matronas. Matrones y matronas critican a su colegio por no llamar a debatir sobre violencia obstétrica. 2017. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Román A. Carta al director del mercurio.

- Mix C. Establece derechos en el ámbito de la gestación, preparto, parto, postparto, aborto, salud ginecólogica y sexual, y sanciona la violencia gineco-obstétrica. 2018. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- González S. Seminario avances en cuidados maternos respetuosos. 2019. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Colegio de Matronas y Matrones de Chile P. Parto Personalizado en La Serena: Una Historia Maravillosa. 2019. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Cabrera Ditzel J. Realidad y expectativa en torno a la atención del parto en Chile: Renacer del parto natural. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2003; 68: 65–67.

- Suárez P E, Oyarzún E E. Atención del parto y reforma de salud. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2007; 72: 137–138.

- Ministerio de Salud Chile. Aprueba reglamento sobre derechos y deberes de las personas en relación a las actividades vinculadas con su atención de salud. DTO-38 26-DIC-2012. 2012. (accessed 17 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- SOCHOG. Reunión Clínica Sochog - mayo 2015. Santiago de Chile. 2015. (accessed 16 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Uribe T C. Como avanzar en consenso hacia las modalidades de parto y nacimiento integral. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2018; 83: 551–552.

- Carvajal Ambiado L, Hernando Perez M. Establece los derechos de la mujer embarazada en relación con su atención antes, durante y después del parto, y modifica el código penal para sancionar la violencia obstétrica. 2015. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Álvarez S, Cicardini D, Fuenzalida G, et al. Modifica la ley N°20.584, que Regula los derechos y deberes que tienen las personas en relación con acciones vinculadas a su atención en salud, para garantizar los derechos del neonato y de las mujeres durante la gestación, el parto y postparto. 2017. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Modifica el Código Penal, para tipificar el delito de maltrato respecto de la mujer embarazada, cometido por los profesionales de la salud que indica. (accessed 27 July 2020). [Internet] | Link |

- Bachelet M. Proyecto de ley sobre el derecho de las mujeres a una vida libre de violencia. 2017. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- WHO. Prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during childbirth. WHO. (accessed 21 July 2020). [Internet] | Link |

- Bachelet VC. El estallido social de Chile y la cancelación del 26 Coloquio de la Colaboración Cochrane. Medwave. 2019 Oct 23;19(9):e7707. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Elm E von, Madrid E, Urrútia G. Chile: civil unrest and Cochrane Colloquium cancelled. Lancet. 2019 Nov 9;394(10210):e35. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Uribe TC, Contreras MA, Hoga L. Presencia activa del padre en el nacimiento integral: significados atribuidos por padres y madres a los roles paternos. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2018; 83: 22–26.

- Uribe TC, Contreras MA, Bravo VP, et al. Modelo de asistencia integral del parto: Concepto de integralidad basado en la calidad y seguridad. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2018; 83: 266–276.

- Villalón UH, Toro GR, Riesco CI, et al. Participación paterna en la experiencia del parto. Revista chilena de pediatría 2014; 85: 554–560.

- Parirnos Chile. Ley contra la violencia ginecobstétrica: una necesidad urgente. Facebook. (accessed 16 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Miles Chile. Primer Informe Salud Sexual, Salud Reproductiva y Derechos Humanos En Chile. 2016. (accessed 23 September 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Diario y Radio Universidad de Chile. Colegio de Matronas: Estamos en contra de todo tipo de violencia contra la mujer. 2019. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

- Oyarzun Ebensperger E. Operación cesárea. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología 2019; 84: 167–168.

- Poblete A, Marques X, Staig P, et al. Estado de violencia obstétrica durante atención del trabajo de parto y parto. Hospital Clínico San Borja Arriarán. 2015. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

The World Medical Association. Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM. Principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas en seres humanos. 1964. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

The World Medical Association. Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM. Principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas en seres humanos. 1964. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link | Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The Belmont Report. Estados Unidos de Norteamérica: Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. 1979. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The Belmont Report. Estados Unidos de Norteamérica: Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. 1979. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link | ACNUDH. Convención sobre la eliminación de todas las formas de discriminación contra la mujer. 1979. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

ACNUDH. Convención sobre la eliminación de todas las formas de discriminación contra la mujer. 1979. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link | ONU Mujeres. Declaración y Plataforma de Acción de Beijing. Declaración política y documentos resultados de Beijing+5. Naciones Unidas. Naciones Unidas. 1995. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

ONU Mujeres. Declaración y Plataforma de Acción de Beijing. Declaración política y documentos resultados de Beijing+5. Naciones Unidas. Naciones Unidas. 1995. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link | Organización Mundial de la Salud. Recomendaciones de la OMS para la conducción del trabajo de parto. OMS. 2015. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

Organización Mundial de la Salud. Recomendaciones de la OMS para la conducción del trabajo de parto. OMS. 2015. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link | Organización Mundial de la Salud. Recomendaciones de la OMS para los cuidados durante el parto, para una experiencia de parto positiva. Transformar la atención a mujeres y neonatos para mejorar su salud y bienestar. 2018. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

Organización Mundial de la Salud. Recomendaciones de la OMS para los cuidados durante el parto, para una experiencia de parto positiva. Transformar la atención a mujeres y neonatos para mejorar su salud y bienestar. 2018. (accessed 3 October 2019). [Internet] | Link | Perdomo-Rubio A, Martínez-Silva PA, Lafaurie-Villamil MM, et al. Discourses on obstetric violence in the latin america newspaper: changes and continuities in the field of health care. Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública 2019; 37: 125–135.

Perdomo-Rubio A, Martínez-Silva PA, Lafaurie-Villamil MM, et al. Discourses on obstetric violence in the latin america newspaper: changes and continuities in the field of health care. Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública 2019; 37: 125–135.  Vera C, Donoso E. Desaceleración en la reducción de la mortalidad materna en Chile impide alcanzar el 5° objetivo de desarrollo del milenio. 2019; 43: 13–20.

Vera C, Donoso E. Desaceleración en la reducción de la mortalidad materna en Chile impide alcanzar el 5° objetivo de desarrollo del milenio. 2019; 43: 13–20.  Binfa L, Pantoja L, Ortiz J, et al. Assessment of the implementation of the model of integrated and humanised midwifery health services in Santiago, Chile. Midwifery 2013; 29: 1151–1157. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Binfa L, Pantoja L, Ortiz J, et al. Assessment of the implementation of the model of integrated and humanised midwifery health services in Santiago, Chile. Midwifery 2013; 29: 1151–1157. | CrossRef | PubMed | Sadler M. Así me nacieron a mi hija. Aportes antropológicos para el análisis de la atención biomédica del parto hospitalario. Universidad de Chile. 2003. [Internet] | Link |

Sadler M. Así me nacieron a mi hija. Aportes antropológicos para el análisis de la atención biomédica del parto hospitalario. Universidad de Chile. 2003. [Internet] | Link | Menéndez EL. Modelo Médico Hegemónico: Reproducción técnica y cultural. Natura Medicatrix: Revista médica para el estudio y difusión de las medicinas alternativas. 1998; 17–22.

Menéndez EL. Modelo Médico Hegemónico: Reproducción técnica y cultural. Natura Medicatrix: Revista médica para el estudio y difusión de las medicinas alternativas. 1998; 17–22.  Castro R. Génesis y práctica del habitus médico autoritario en México. Revista mexicana de sociología 2014; 76: 167–197.

Castro R. Génesis y práctica del habitus médico autoritario en México. Revista mexicana de sociología 2014; 76: 167–197.  Foucault M. El nacimiento de la clínica: una arqueología de la mirada médica. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 2011.

Foucault M. El nacimiento de la clínica: una arqueología de la mirada médica. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 2011.  Sandall J, Hatem M, Devane D, et al. Discussions of findings from a Cochrane review of midwife-led versus other models of care for childbearing women: continuity, normality and safety. Midwifery 2009; 25: 8–13. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sandall J, Hatem M, Devane D, et al. Discussions of findings from a Cochrane review of midwife-led versus other models of care for childbearing women: continuity, normality and safety. Midwifery 2009; 25: 8–13. | CrossRef | PubMed | Ministerio de Salud Chile. Manual de atención personalizada en el proceso reproductivo. Santiago de Chile. 2008. [Internet] | Link |

Ministerio de Salud Chile. Manual de atención personalizada en el proceso reproductivo. Santiago de Chile. 2008. [Internet] | Link | Belli LF. La violencia obstétrica: otra forma de violación a los derechos humanos. 2013. (accessed 30 August 2019). [Internet] | Link |

Belli LF. La violencia obstétrica: otra forma de violación a los derechos humanos. 2013. (accessed 30 August 2019). [Internet] | Link | Benitez G. Violencia obstétrica. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina 2008; 31: 5–6.

Benitez G. Violencia obstétrica. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina 2008; 31: 5–6.  Gobierno de México. Senado aprueba sancionar violencia obstétrica. 2014. (accessed 30 August 2019). [Internet] | Link |

Gobierno de México. Senado aprueba sancionar violencia obstétrica. 2014. (accessed 30 August 2019). [Internet] | Link | Williams CR, Jerez C, Klein K, et al. Obstetric violence: a Latin American legal response to mistreatment during childbirth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2018; 125: 1208–1211. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Williams CR, Jerez C, Klein K, et al. Obstetric violence: a Latin American legal response to mistreatment during childbirth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2018; 125: 1208–1211. | CrossRef | PubMed | Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13: 141–146. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13: 141–146. | CrossRef | PubMed | Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467. | CrossRef | PubMed | Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2009; 46: 1386–1400. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2009; 46: 1386–1400. | CrossRef | PubMed | Hernández Sampieri R, Fernández Collado C, Baptista Lucio P, et al. Metodología de la investigación. 6 ed. México, D.F.: McGraw-Hill Education, 2012.

Hernández Sampieri R, Fernández Collado C, Baptista Lucio P, et al. Metodología de la investigación. 6 ed. México, D.F.: McGraw-Hill Education, 2012.  Flick U. El diseño de investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata. 2015. (accessed 4 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

Flick U. El diseño de investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata. 2015. (accessed 4 October 2019). [Internet] | Link | Sadler M, Santos MJDS, Ruiz-Berdún D, et al. Moving beyond disrespect and abuse: addressing the structural dimensions of obstetric violence. Reprod Health Matters. 2016 May;24(47):47-55. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sadler M, Santos MJDS, Ruiz-Berdún D, et al. Moving beyond disrespect and abuse: addressing the structural dimensions of obstetric violence. Reprod Health Matters. 2016 May;24(47):47-55. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLOS Medicine 2015; 12: e1001847. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLOS Medicine 2015; 12: e1001847. | CrossRef | PubMed | Arguedas Ramírez G. La violencia obstétrica: propuesta conceptual a partir de la experiencia costarricense. Cuadernos Inter cambio sobre Centroamérica y el Caribe; 11. 2014. (accessed 21 July 2020). [Internet] | Link |

Arguedas Ramírez G. La violencia obstétrica: propuesta conceptual a partir de la experiencia costarricense. Cuadernos Inter cambio sobre Centroamérica y el Caribe; 11. 2014. (accessed 21 July 2020). [Internet] | Link | Van Dijk TA. Estructuras y funciones del discurso. Siglo XXI. 2005. (accessed 4 October 2019). [Internet] | Link |

Van Dijk TA. Estructuras y funciones del discurso. Siglo XXI. 2005. (accessed 4 October 2019). [Internet] | Link | Cisterna I. Una experiencia en Villarrica. In: Evolución de la Matronería en Chile Hitos y Desafíos. Santiago de Chile, pp. 109–113.

Cisterna I. Una experiencia en Villarrica. In: Evolución de la Matronería en Chile Hitos y Desafíos. Santiago de Chile, pp. 109–113.  Leiva G. Desarrollo del rol profesional en los procesos de humanización de la atención del parto. In: Evolución de la Matronería en Chile Hitos y Desafíos. Santiago de Chile, pp. 95–107.

Leiva G. Desarrollo del rol profesional en los procesos de humanización de la atención del parto. In: Evolución de la Matronería en Chile Hitos y Desafíos. Santiago de Chile, pp. 95–107.  Leiva Rojas G, Sadler M. Nacer en Chile del siglo XXI: el sistema de salud como un determinante social crítico en la atención del nacimiento. Chile: Universidad del Desarrollo. 2016. [Internet] | Link |

Leiva Rojas G, Sadler M. Nacer en Chile del siglo XXI: el sistema de salud como un determinante social crítico en la atención del nacimiento. Chile: Universidad del Desarrollo. 2016. [Internet] | Link | Leighton Naranjo A, Monsalve Treskow D, Ibacache Burgos J. Nacer en Chiloé: articulación de conocimientos para la atención del proceso reproductivo. Cuad méd-soc (Santiago de Chile) 2008; 174–191.

Leighton Naranjo A, Monsalve Treskow D, Ibacache Burgos J. Nacer en Chiloé: articulación de conocimientos para la atención del proceso reproductivo. Cuad méd-soc (Santiago de Chile) 2008; 174–191.  Leiva Rojas G, Sadler M. Nacer en el Chile del Siglo XXI: el sistema de salud como un determinante social crítico en la atención del nacimiento. In: Vulnerabilidad social y su efecto en salud en Chile: Desde la comprensión del fenómeno hacia la implementación de soluciones, pp. 61–77.

Leiva Rojas G, Sadler M. Nacer en el Chile del Siglo XXI: el sistema de salud como un determinante social crítico en la atención del nacimiento. In: Vulnerabilidad social y su efecto en salud en Chile: Desde la comprensión del fenómeno hacia la implementación de soluciones, pp. 61–77.  Sadler M. Revisión del parto personalizado. Herramientas y experiencias en Chile. Santiago de Chile. 2009. (accessed 26 January 2018). [Internet] | Link |