Key Words: Nosocomial pneumonia, Risk factors, Hypoalbuminemia, Anemia, Perú

Abstract

Objective

To determine how clinical and laboratory factors were associated with nosocomial pneumonia in adult patients hospitalized in an internal medicine department.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective unmatched case-control study. We recorded clinical and epidemiological data from patients discharged from an internal medicine department of a Peruvian reference hospital, the Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza, between 2016 and 2018. Bivariate and multivariate analyses (using logistic regression models) were performed to obtain crude and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. We calculated the population attributable fraction of the significant variables.

Results

We analyzed 138 cases and 200 controls, with a mean age of 72.6 ± 17.8 years (21 to 104) for cases and 71.7 ± 15.3 years (19 to 98) for controls. The multivariate analysis indicated that severe anemia (adjusted odds ratio 9.0, confidence interval 95% 1.9 to 43.1, P = 0.01), severe hypoalbuminemia (adjusted odds ratio 4.0, confidence interval 95% 1.2 to 13.8, P = 0.03), altered state of consciousness (adjusted odds ratio 3.6, confidence interval 95% 1.6 to 8.2, P = 0.00), and prior use of antibiotics (adjusted odds ratio 6.3, confidence interval 95% 2.7 to 14.5, P = 0.00) were significantly associated with nosocomial pneumonia. The population attributable fraction found were 41.8% for altered state of consciousness, 33.2% for severe anemia, and 36.3% for severe hypoalbuminemia.

Conclusion

Clinical and laboratory risk factors associated with nosocomial pneumonia development in adult patients hospitalized in an internal medicine department were severe anemia, severe hypoalbuminemia, altered consciousness, and previous use of antibiotics.

|

Main messages

|

Introduction

Nosocomial pneumonia is the most frequent in-hospital infection with a prevalence maintained in recent years [1] and is responsible for high morbidity and mortality worldwide [2]. This infection accounts for 22% of all hospital-acquired infections [3]. It prolongs hospital stay from four to 16 days [4],[5], it generates costs of approximately 39,897 dollars [6], and it has a mortality rate between 14 to 30% [4],[5],[7],[8]. In most cases, nosocomial pneumonia occurs in conventional hospital wards, with an incidence of three to seven cases per 1000 hospital admissions [10].

Most etiologic and epidemiologic studies address nosocomial pneumonia among critically ill patients, most of which require mechanical ventilation. The scientific evidence on nosocomial pneumonia in non-ventilated patients is mainly extrapolated from intensive care unit studies, generating a knowledge gap [2]. Therefore, it is essential to strengthen prevention measures among this population due to its deleterious outcomes [1] and determine the associated risk factors.

In 2017 worldwide, it was estimated that anemia caused 58 200 000 years lived with disability and a global age-standardized rate of 783 years lived with disability per 100 000 people; constituting the health condition that generated the largest burden of all [11]. Therefore, anemia has significant consequences on health and social and economic development in countries with low and high economic resources [12]. Having anemia within hospital admission is considered part of the patient's underlying diseases [13]. This comorbidity is frequent and related to hypoxia, which induces nosocomial infections [8].

Malnutrition is one of the most significant health and development challenges of our time. It affects at least one in three people globally, including 815 000 000 people chronically undernourished [14]. Hypoalbuminemia is one of the simplest and most widely used markers for measuring malnutrition [15]. Hypoalbuminemia is associated with the acquisition and severity of infectious diseases and is necessary for an adequate immune response [16]. Although serum albumin may be decreased by diseases causing acute inflammatory states during hospitalization, the prolonged half-life of this protein would allow an adequate reflection of baseline nutritional status when albumin is measured at patient admission. It has been observed that albumin measured at hospital admission is linked to the development of nosocomial infections and increased mortality [17]. Several authors have reported other factors associated with nosocomial pneumonia, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure [18], altered consciousness [19], and previous antibiotic use [20].

In all, this study aims to determine how clinical and laboratory factors are associated with nosocomial pneumonia in adult patients hospitalized in the internal medicine service at the Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza from 2016 to 2018.

Methods

Design

An observational and analytical retrospective study was conducted with an unmatched case-control design.

Context

The information was gathered through collection cards using medical records of patients who presented with a nosocomial pneumonia diagnosis and were later discharged from the Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza, which belongs to the Ministry of Health and is located in Lima, Peru. The patients were seen between January 2016 and December 2018.

Selection of participants

Eligible patients were hospitalized for 48 hours or more and aged 18 years or older. Patients who could have acquired nosocomial pneumonia in the intensive care unit (stay in the intensive care unit in the previous 10 days) and patients whose clinical history was not available in the hospital file were excluded. For each case subject, two controls were scheduled to be included.

A case was considered to be an adult patient discharged from the internal medicine department of the Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza, who presented a diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia reported in the clinical history. Meanwhile, any adult patient discharged from the internal medicine department of the Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza without a diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia was considered a control. Patients diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diffuse interstitial lung disease, and heart failure were included according to the codification of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition, ICD-10.

Variables and their operationalization

Clinical and laboratory variables were evaluated within the first 72 hours of admission. The outcome variable of interest was the diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia (according to the correct clinical and radiological diagnosis recorded in the respective clinical records).

The clinical and laboratory variables included:

- Hypoalbuminemia: defined as serum albumin less than 3.5 grams per deciliter; mild 3.5 to 3 grams per deciliter, moderate 2.9 to 2.4 grams per deciliter and severe less than 2.4 grams per deciliter [21].

- Anemia: women with hemoglobin levels below 12 grams per deciliter were considered to have mild anemia, below 11 grams per deciliter moderate anemia, and below eight grams per deciliter severe anemia [22]. Males with hemoglobin levels less than 13 grams per deciliter were considered to have mild anemia, less than 11 grams per deciliter moderate anemia, and less than 8 grams per deciliter severe anemia [22].

- Chronic kidney disease: was defined as a diagnosis or history of chronic kidney disease in the clinical history, considering a glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 milligrams per deciliter for at least three months.

- Altered consciousness: defined as the presence of any degree of altered state of consciousness at diagnosis (or in the previous 72 hours) of nosocomial pneumonia [8]. The intervening physician objectified the altered consciousness with a Glasgow scale of less than 15.

- Endotracheal intubation: was considered within the two weeks before the onset of nosocomial pneumonia [8].

- Hospital admission in the previous month: defined as a hospital admission within the previous month [8].

- Previous antibiotic use: defined as an antibiotic treatment within two weeks before the nosocomial pneumonia and with a duration of more than 48 hours [8].

- Use of corticosteroids: recorded in the medical indication sheet of the medical record.

- Use of anti-ulcer drugs: use of proton pump inhibitors or histamine H2-receptor antagonists for at least seven days in the 15 days before the onset of nosocomial pneumonia [8].

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated following the sampling formula for unmatched case-control studies, using an expected odds ratio of 1.9 for anemia based on previous studies [8], considering a 95% confidence interval, a margin of error of 5%, a proportion of exposure in controls of 50%, and with 80% statistical power. The above analysis determined that 102 cases and 204 controls were required for this study.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS v 25 - IBM (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences -International Business Machines Corporation). The descriptive results were presented and organized as frequency tables and graphs. Analytical results were presented in double-entry tables and bar graphs. In the bivariate analysis, the Chi-square test and P value < 0.05 were used to determine the significance level of the association. Odds ratios were used to determine the strength of association between the study variables. In the multivariate logistic regression model, adjusted odds ratios were used, and a significance level of P < 0.05 was considered. The population attributable fraction was calculated for the significant variables in the multivariate analysis, using the formula proposed by Parkin et al. [23].

(p1 X ERR1) + (p2 X ERR2) + (p3 X ERR3)... + (pn X ERRn)

1+ [(p1 X ERR1) + (p2 X ERR2) + (p3 X ERR3)... + (pn X ERRn)]

Where p1 is the proportion of the population at exposure level 1 (and so forth), and ERR1 is the excess relative risk (relative risk - 1) at exposure level 1 (and so forth).

Ethics

The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional research ethics committee of the Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza with the official letter No. 041 - 19 - HNAL - CII - 2019. An anonymous list was used for the analysis using numerical codes to identify the data collection cards of each patient. In this way, the confidentiality and privacy of the subjects involved in the research were maintained. The study was approved by the Institute for Research in Biomedical Sciences of the Ricardo Palma University, registered by the university council N° 2583 - 2018.

Results

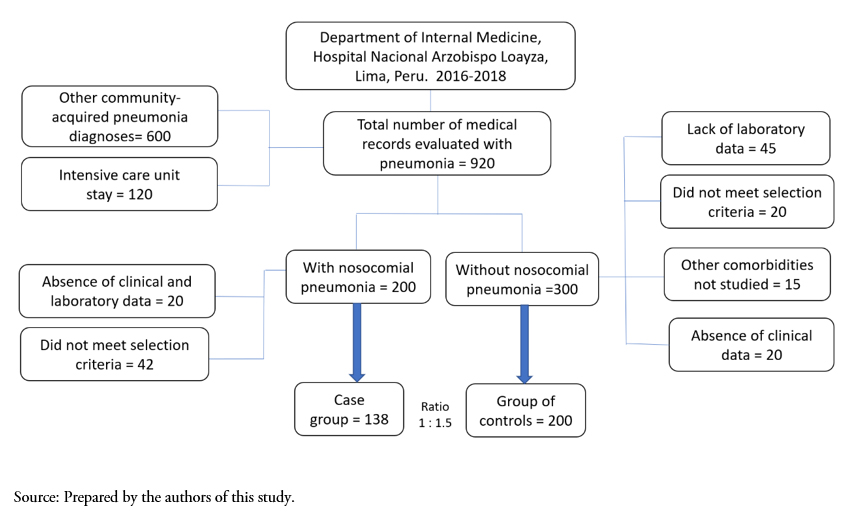

The study consisted of 138 cases and 200 controls (Figure 1) that showed a similar distribution by age and sex.

Figure 1. Unmatched case-control flowchart.

The controls were diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diffuse interstitial lung disease, and heart failure. Within the cases, the mean age was 72.6 ± 17.8 years (21 to 104), while in the control group, the mean age was 71.7 ± 15.3 years (19 to 98). In the cases group, the distribution of patients according to age groups was 18 to 54 years: 16.7% (23), 55 to 74 years: 29% (40), and older or equal to 75 years: 54.3% (75). While in the control group, the distribution of patients according to age groups was 18 to 54 years: 14.5% (29), 55 to 74 years: 33% (66), and older or equal to 75 years: 52.5% (105). Within cases, 65.2% (n = 90) were females and 34.8% (n = 48) were males, and within controles 71.5% (n = 143) were females and 28.5% (n = 57) were males. Among cases, mean albumin values were 2.84 grams per deciliter (standard deviation ± 0.77) and in controls 3.37 grams per deciliter (standard deviation ± 0.66). In cases, mean hemoglobin values were 10.43 grams per deciliter (standard deviation ± 2.45) and in controls 12.19 grams per deciliter (standard deviation ± 2.24).

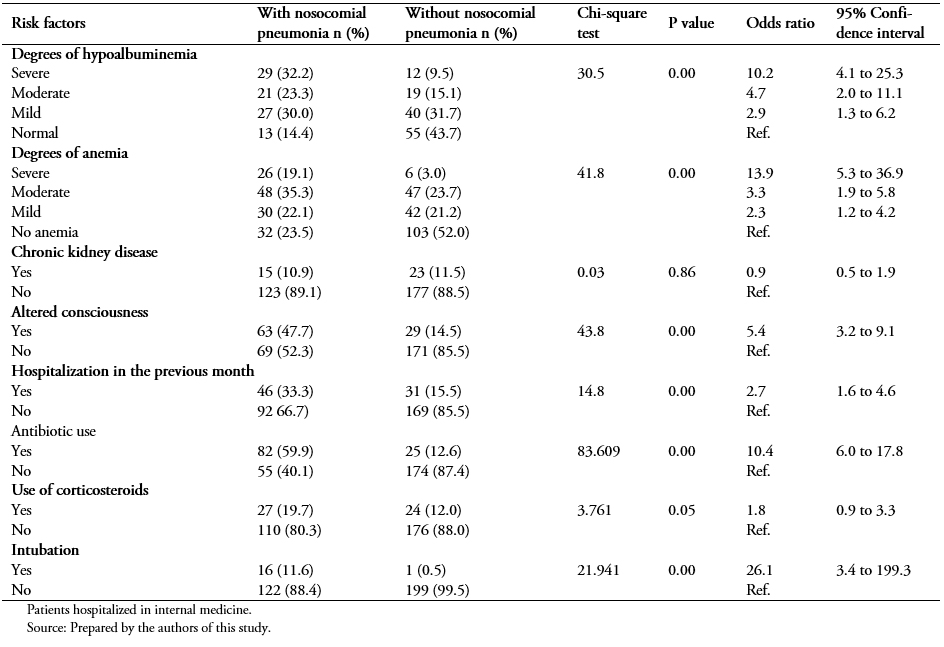

On a bivariate analysis, the intrinsic risk factors significantly associated with nosocomial pneumonia were: severe anemia (hemoglobin less than 8 grams per deciliter, odds ratio 13.9, 95% confidence interval 5.3 to 36.9, P < 0.05), moderate anemia (hemoglobin less than 11 grams per deciliter, odds ratio 3.3, 95% confidence interval 1.9 to 5.8, P < 0.05) and mild anemia (hemoglobin less than 12 grams per deciliter in females and hemoglobin less than 13 grams per deciliter in males, odds ratio 2.3, 95% confidence interval 1.2 to 4.2 P < 0.05); severe hypoalbuminemia (less than 2.4 grams per deciliter, odds ratio 10.2, 95% confidence interval 4.1 to 25.3, P < 0.05), moderate hypoalbuminemia (2.9 to 2.4 grams per deciliter, odds ratio 4.7, 95% confidence interval 2.0 to 11.1, P < 0.05), mild hypoalbuminemia (3.5 to 3 grams per deciliter, odds ratio 2.9, 95% confidence interval 1.3 to 6.2 P < 0.05); and altered consciousness (odds ratio 5.4, 95% confidence interval 3.2 to 9.1, P < 0.05). The extrinsic risk factors significantly associated with nosocomial pneumonia were endotracheal intubation (odds ratio 26.1, 95% confidence interval 3.4 to 199.3, P < 0.05), hospitalization in the previous month (odds ratio 2.7, 95% confidence interval 1.6 to 4.6, P < 0.05), previous antibiotic use (odds ratio 10.4, 95% confidence interval 6.0 to 17.8, P < 0.05) and previous antiulcer use (odds ratio 6.5, 95% confidence interval 3.0 to 14.1, P < 0.05) (Table. 1).

Table 1. Bivariate analysis of risk factors associated with nosocomial pneumonia.

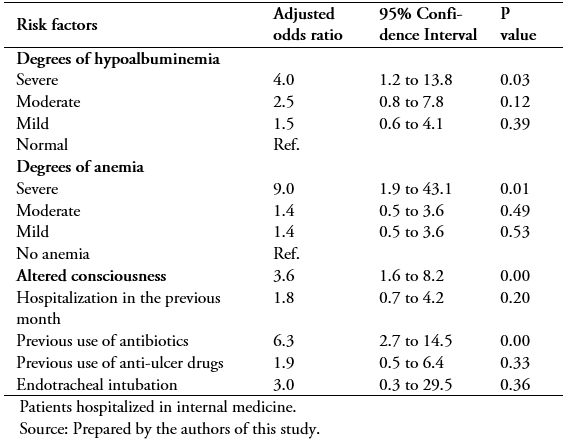

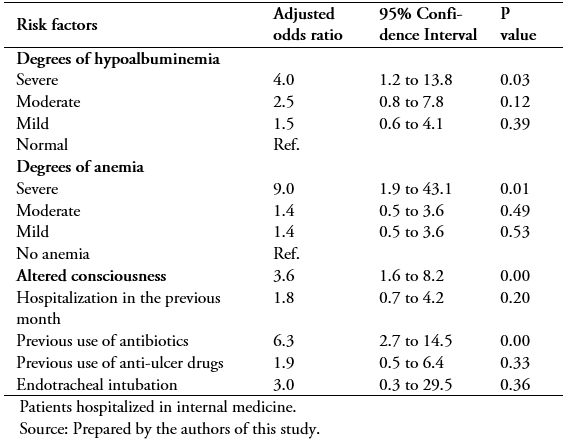

In a multivariate analysis, the independent risk factors significantly associated with nosocomial pneumonia were severe hypoalbuminemia (adjusted odds ratio 4.0, 95% confidence interval 1.2 to 13.8, P = 0.03), severe anemia (adjusted odds ratio 9.0, 95% confidence interval 1.9 to 43.1, P = 0.01), altered consciousness (adjusted odds ratio 3.6, 95% confidence interval 1.6 to 8.2, P < 0.05) and previous antibiotic use (adjusted odds ratio 6.3, 95% confidence interval 2.7 to 14.5, P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with nosocom-ial pneumonia.

In addition, the impact of the variables associated with nosocomial pneumonia was estimated using the population attributable fraction (Table 3).

Table 3. Population attributable fraction of risk factors associated with nosocomial pneumonia.

Discussion

This study found that severe anemia, severe hypoalbuminemia, altered consciousness, and previous antibiotic use were significantly associated with having nosocomial pneumonia in hospitalized patients outside the intensive care unit. Nosocomial pneumonia is an actual public health and hospital management problem. Moreover, it has a prevalence that has been maintained in recent years, suggesting that more work needs to be done on its prevention [1]. Likewise, it is a significant cause of morbidity, mortality, and health costs [6]. Therefore, analyzing the risk factors for nosocomial pneumonia would provide us with the theoretical basis and scientific evidence for the possible future implementation of effective prevention measures.

We found that the risk of acquiring nosocomial pneumonia increased with hypoalbuminemia severity. Among patients with mild hypoalbuminemia, the risk of nosocomial pneumonia increased 1.5 times compared with patients with normal albumin. Furthermore, the risk increased 2.5 times among patients with moderate hypoalbuminemia, although statistical significance was not reached. In contrast, patients with severe hypoalbuminemia had four times the risk of developing nosocomial pneumonia compared with patients with normal albumin, being this association statistically significant.

There is a pathophysiological mechanism proposed for this underlying this association. Within the first days of hospitalization – and especially in malnourished patients –, the oropharyngeal cavity can be colonized by pathogenic bacteria that ultimately, through microaspirations of contaminated secretions, provokes nosocomial pneumonia [2]. A previous case-control study found that malnutrition (measured by hypoalbuminemia) was a risk factor that increased the probability of acquiring nosocomial pneumonia by 3.4 times (adjusted odds ratio 3.4, 95% confidence interval 1.35 to 8.65, P < 0.05). Therefore, it was recommended that patients with hypoalbuminemia be carefully monitored as this is a marker of poor nutritional status [8].

Hypoalbuminemia may decrease the immune response and predispose to infections causing complications. This association was also observed in a retrospective study among stroke patients, where hypoalbuminemia independently predicted the acquisition of nosocomial pneumonia (adjusted odds ratio 0.9, 95% confidence interval 0.91 to 0.98 P < 0.05) [24]. The above is also consistent with a prospective study where a low serum albumin level was found to be an independent predictor, which increased the risk of nosocomial pneumonia in elderly patients by 15-fold (adjusted odds ratio 14.7, 95% confidence interval 4.0 to 54.8, P < 0.05) [25].

Furthermore, in a retrospective study in patients with intestinal failure, decreased albumin was found to be a significant predictor of in-hospital infections, including nosocomial pneumonia (adjusted odds ratio 0.9, 95% confidence interval 0.88 to 0.98, P < 0.05) [26]. On the other hand, albumin in normal ranges was a protective factor for acquiring nosocomial pneumonia in elderly stroke patients [27]. These findings suggest the potential benefits of adequate nutrition for infection prevention, which could be explained by the immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and endothelial protective properties that albumin exerts to contribute to reaching healthy homeostasis [28].

Concerning anemia, it was observed that as the severity increased, the risk of acquiring nosocomial pneumonia also increased. Patients with mild and moderate anemia had 1.4 times more risk of acquiring nosocomial pneumonia than patients with normal hemoglobin. However, this association was not significant. Patients with severe anemia had nine times the risk of nosocomial pneumonia compared with controls, being association statistically significant. The likely pathophysiology reveals that anemia generates hypoxia, which increases the risk of nosocomial infections [8]. In addition, iron deficiency anemia is responsible for dysfunction of the innate and adaptive immune system, decreasing the antimicrobial response [29].

It is critical to note that severe anemia was the factor that most increased the risk for nosocomial pneumonia in the present study. In a previous case-control study, anemia defined as hemoglobin levels below 10 grams per deciliter (which is included in the moderate and severe categories) was found to be an independent factor that increased twice the risk of acquiring nosocomial pneumonia among adult patients hospitalized outside the intensive care unit (adjusted odds ratio 2.1, 95% confidence interval 1.12 to 3.85, P = 0.02) [8]. Similarly, among patients with ischemic stroke, anemia was shown to be an independent predictor that increased the risk of developing nosocomial pneumonia by 1.7-fold (adjusted odds ratio 1.7, 95% confidence interval 1.35 to 2.17, P < 0.05) [30].

Altered consciousness was another independent risk factor that increased 3.6 times the probability of acquiring nosocomial pneumonia compared with controls. Altered consciousness favors microaspiration of secretions from the oropharynx and stomach, which pathogenic bacteria can colonize after a few days of hospitalization [2]. Similar results were observed in a large prospective cohort study where intensive care unit patients were followed for four years. This study showed that altered consciousness is an independent risk factor that doubles the risk of acquiring nosocomial pneumonia (relative risk 2.0, 95% confidence interval 1.5 to 2.7) [19]. In a case-control study of patients hospitalized in wards other than the intensive care unit, altered consciousness was also found to be an independent predictor, which increased twice the risk of developing nosocomial pneumonia (adjusted odds ratio 2.1, 95% confidence interval 1.01 to 4.52, P < 0.05) [8]. Similarly, in a prospective study conducted in an intensive care unit, altered consciousness was an independent predictor of the development of nosocomial pneumonia associated with mechanical ventilation (relative risk 4.8, 95% confidence interval 1.17 to 13.84, P = 0.03).

In our study, the use of antibiotics within the two weeks before the event was an independent risk factor that increased the probability of acquiring nosocomial pneumonia by sixfold. This association is relevant as it is a potentially modifiable factor by training physicians in the rational and individualized use of antimicrobials within inpatient and outpatient settings. Similarly, another case-control study showed that antibiotic use in the previous six weeks was significantly associated with developing nosocomial pneumonia in internal medicine wards (P < 0.05) [31]. A retrospective study observed that the proportion of pneumonia associated with mechanical ventilation was five times higher in patients who received more than three antibiotics than those treated with fewer antibiotics. (adjusted odds ratio 5, 95% confidence interval 1.77 to 13.85, P < 0.01) [20]. According to a prospective study performed in an intensive care unit, the prolonged use of antibiotics (more than 24 hours) was an independent predictor that increased the risk of pneumonia associated with late-onset mechanical ventilation by ninefold in patients with head injury or stroke (adjusted odds ratio 9.2, 95% confidence interval 1.7 to 51.3, P < 0.01) [32]. Likewise, a prospective study of intensive care unit patients found that multiple episodes of inadequate antibiotic therapy increased the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria by eightfold (adjusted odds ratio 7.9, 95% confidence interval 6.52 to 8.39, P = 0.01) [33]. In a retrospective study, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics within 10 days before diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia was an independent predictor of infection by multidrug-resistant bacteria, increasing the risk by 3.5-fold (adjusted odds ratio 3.5, 95% confidence interval 1.56 to 7.61, P < 0.05) [34].

Concerning the population attributable fraction, we found that the values attributable to altered consciousness, severe hypoalbuminemia, and severe anemia were 42%, 36%, and 33%, respectively. In this context, preventing and correcting hypoalbuminemia, anemia, and altered consciousness would impact the development of nosocomial pneumonia among hospitalized adult patients.

It is relevant to note that our study population corresponded mainly to elderly patients with a diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia outside the intensive care unit. Likewise, we should keep in mind that the studied clinical and laboratory parameters are easily accessible, reproducible, preventable, and were reliable predictors for the development of nosocomial pneumonia.

Our study had some limitations, such as being performed in a single institution and not having albumin data available in all patients. Likewise, the anthropometric variables were not always recorded in the registries. Given the study's retrospective nature, it was not possible to evaluate other variables such as polypharmacy, other comorbidities, weight loss, multiple diagnostic procedures, and prolonged hospital stay. However, the population corresponded to a national referral hospital, and the case-control design was robust, providing initial evidence that further prospective and multicenter studies should confirm.

Conclusions

Severe anemia, severe hypoalbuminemia, altered consciousness, and previous antibiotic use were independent risk factors for the development of nosocomial pneumonia among adult patients hospitalized in an internal medicine department.

Since this is an initial study, it is necessary to carry out new prospective and multicenter studies to confirm the presented findings.

Notes

Contributor roles

GHJ, JACV: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, research, resourcing, data curation, writing, first draft, review, revision, editing, visualization, supervision, project management, and obtaining funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Peruvian American Medical Society (PAMS) for their valuable contribution and support for the development of this research work. We also thank the Department of Internal Medicine of the Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza and the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad Ricardo Palma for their valuable collaboration.

Competing interests

The authors completed the ICMJE conflict of interest statement and declared that they received no funds for the completion of this article; they have no financial relationships with organizations that may have an interest in the published article in the last three years and they have no other relationships or activities that may influence the publication of the article. Forms can be requested by contacting the responsible author or the Editorial Committee of the Journal.

Funding

The present work was funded by a grant awarded by the Peruvian American Medical Society (PAMS), January 16 2019.

Ethics

The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional research ethics committee of the Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza with the official letter N° 041 - 19 - HNAL - CII - 2019. The study was registered and approved by the Institute for Research in Biomedical Sciences of the Ricardo Palma University, registered by university council agreement N° 2583 - 2018.

Data sharing statement

The thesis from which this article was derived is available at:

https://repositorio.urp.edu.pe/handle/URP/3778

Language of submission

Spanish.

Figure 1. Unmatched case-control flowchart.

Figure 1. Unmatched case-control flowchart.

Table 1. Bivariate analysis of risk factors associated with nosocomial pneumonia.

Table 1. Bivariate analysis of risk factors associated with nosocomial pneumonia.

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with nosocom-ial pneumonia.

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with nosocom-ial pneumonia.

Table 3. Population attributable fraction of risk factors associated with nosocomial pneumonia.

Table 3. Population attributable fraction of risk factors associated with nosocomial pneumonia.

Introducción

La neumonía nosocomial es la infección intrahospitalaria más frecuente y es responsable de alta morbimortalidad en todo el mundo, por lo que su estudio es muy importante.

Objetivo

Determinar cómo los factores clínicos y de laboratorio se asociaron a neumonía nosocomial en pacientes adultos hospitalizados en un servicio de medicina interna.

Métodos

Se realizó un estudio retrospectivo de casos y controles no pareado. Se recolectaron los datos clínicos epidemiológicos de pacientes egresados del departamento de medicina interna durante el periodo 2016 a 2018 de un centro de referencia en Perú: el Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza. Se realizó análisis bivariado y multivariado, usando el método de regresión logística, para obtener Odds ratio crudos y ajustados, con un intervalo de confianza de 95%. El valor p < 0,05 fue considerado significativo. Se calculó la fracción atribuible poblacional de las variables significativas.

Resultados

Se analizaron 138 casos y 200 controles, la media de edad fue de 72,6 ± 17,8 años (21 a 104) para los casos y 71,7 ± 15,3 años (19 a 98) para los controles. En el análisis multivariado la anemia severa (Odds ratio ajustado: 9,0; intervalo de confianza 95%: 1,9 a 43,1; p = 0,01), hipoalbuminemia severa (Odds ratio ajustado: 4,0; intervalo de confianza 95%: 1,2 a 13,8; p = 0,03), trastorno de conciencia (Odds ratio ajustado: 3,6; intervalo de confianza 95%: 1,6 a 8,2; p = 0,00) y el uso previo de antibióticos (Odds ratio ajustado: 6,3; intervalo de confianza 95%: 2,7 a 14,5; p = 0,00) se asociaron independientemente con la neumonía nosocomial. La fracción atribuible poblacional encontrada fue 41,8% para trastorno de conciencia, 33,2% para anemia severa y 36,3% para hipoalbuminemia severa.

Conclusiones

Los factores de riesgos clínicos y de laboratorio asociados al desarrollo de neumonía nosocomial en pacientes adultos hospitalizados fueron la anemia severa, la hipoalbuminemia severa, el trastorno de conciencia y el uso previo de antibióticos.

Authors:

Gonzalo Huaman Junco[1], Jhony A. De La Cruz-Vargas[1]

Authors:

Gonzalo Huaman Junco[1], Jhony A. De La Cruz-Vargas[1]

Affiliation:

[1] Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencias Biomédicas, Universidad Ricardo Palma, Lima, Perú

E-mail: jhony.delacruz@urp.edu.pe

Author address:

[1] Avenida Coronel Portillo 376,

San Isidro

Lima, Perú

Citation: Huaman Junco G, De La Cruz-Vargas JA. Clinical and laboratory factors associated with nosocomial pneumonia in adult patients in the internal medicine department of a national hospital in Peru: A case-control study. Medwave 2021;21(9):e8482 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2021.09.8482

Submission date: 4/1/2021

Acceptance date: 5/10/2021

Publication date: 29/10/2021

Origin: Not commissioned

Type of review: Externally peer-reviewed by four peer reviewers, double-blind in the first round of review

Comments (0)

We are pleased to have your comment on one of our articles. Your comment will be published as soon as it is posted. However, Medwave reserves the right to remove it later if the editors consider your comment to be: offensive in some sense, irrelevant, trivial, contains grammatical mistakes, contains political harangues, appears to be advertising, contains data from a particular person or suggests the need for changes in practice in terms of diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic interventions, if that evidence has not previously been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No comments on this article.

To comment please log in

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics.

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics. There may be a 48-hour delay for most recent metrics to be posted.

- Magill SS, O'Leary E, Janelle SJ, Thompson DL, Dumyati G, Nadle J, et al. Changes in Prevalence of Health Care-Associated Infections in U.S. Hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 1;379(18):1732-1744. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Di Pasquale M, Aliberti S, Mantero M, Bianchini S, Blasi F. Non-Intensive Care Unit Acquired Pneumonia: A New Clinical Entity? Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Feb 25;17(3):287. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63(5):e61-e111. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Micek ST, Chew B, Hampton N, Kollef MH. A Case-Control Study Assessing the Impact of Nonventilated Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia on Patient Outcomes. Chest. 2016 Nov;150(5):1008-1014. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014 Mar 27;370(13):1198-208. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Giuliano KK, Baker D, Quinn B. The epidemiology of nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2018 Mar;46(3):322-327. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Davis J, Finley D: The breadth of hospital-acquired pneumonía: nonventilated versus ventilated patients in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Patient Safety Advisory. 2012;9(3):99-105. | Link |

- Sopena N, Heras E, Casas I, Bechini J, Guasch I, Pedro-Botet ML, et al. Risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia outside the intensive care unit: a case-control study. Am J Infect Control. 2014 Jan;42(1):38-42. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- See I, Chang J, Gualandi N, Buser GL, Rohrbach P, Smeltz DA, et al. Clinical Correlates of Surveillance Events Detected by National Healthcare Safety Network Pneumonia and Lower Respiratory Infection Definitions-Pennsylvania, 2011-2012. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Jul;37(7):818-24. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Huaman-Junco G. Factores de riesgo asociados a neumonía nosocomial en pacientes adultos. Rev Fac Med Hum. 2019;19(1):80-89. | CrossRef |

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018 Nov 10;392(10159):1789-1858. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- World Health Organization. Nutritional anaemias: tools for effective prevention and control. WHO [on line]. | Link |

- Koch CG, Li L, Sun Z, Hixson ED, Tang AS, Phillips SC, et al. From Bad to Worse: Anemia on Admission and Hospital-Acquired Anemia. J Patient Saf. 2017 Dec;13(4):211-216. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- O'Shea E, Trawley S, Manning E, Barrett A, Browne V, Timmons S. Malnutrition in Hospitalised Older Adults: A Multicentre Observational Study of Prevalence, Associations and Outcomes. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(7):830-836. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Bohl DD, Shen MR, Kayupov E, Della Valle CJ. Hypoalbuminemia Independently Predicts Surgical Site Infection, Pneumonia, Length of Stay, and Readmission After Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016 Jan;31(1):15-21. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Wiedermann CJ. Hypoalbuminemia as Surrogate and Culprit of Infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Apr 26;22(9):4496. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Nakano H, Hashimoto H, Mochizuki M, Naraba H, Takahashi Y, Sonoo T, et al. Hypoalbuminemia on Admission as an Independent Risk Factor for Acute Functional Decline after Infection. Nutrients. 2020 Dec 23;13(1):26. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Strassle PD, Sickbert-Bennett EE, Klompas M, Lund JL, Stewart PW, Marx AH, et al. Incidence and risk factors of non-device-associated pneumonia in an acute-care hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020 Jan;41(1):73-79. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Guzmán-Herrador B, Molina CD, Allam MF, Navajas RF. Independent risk factors associated with hospital-acquired pneumonia in an adult ICU: 4-year prospective cohort study in a university reference hospital. J Public Health (Oxf). 2016 Jun;38(2):378-83. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Xu Y, Lai C, Xu G, Meng W, Zhang J, Hou H,et al. Risk factors of ventilator-associated pneumonia in elderly patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Clin Interv Aging. 2019 Jun 7;14:1027-1038. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Jesus SR, Alves BP, Golin A, Mairin S, Dachi L, Marques A, et al. Association of anemia and malnutrition in hospitalized patients with exclusive enteral nutrition. Nutr Hosp. 2018 Jun 22;35(4):753-760. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Concentraciones de hemoglobina para diagnosticar la anemia y evaluar su gravedad. OMS. [on line]. | Link |

- Parkin DM. 1. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010. Br J Cancer. 2011 Dec 6;105 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S2-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Dziedzic T, Pera J, Klimkowicz A, Turaj W, Slowik A, Rog TM, et al. Serum albumin level and nosocomial pneumonia in stroke patients. Eur J Neurol. 2006 Mar;13(3):299-301. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Hanson LC, Weber DJ, Rutala WA. Risk factors for nosocomial pneumonia in the elderly. Am J Med. 1992 Feb;92(2):161-6. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Yang J, Sun H, Wan S, Mamtawla G, Gao X, Zhang L, et al. Prolonged Parenteral Nutrition Is One of the Most Significant Risk Factors for Nosocomial Infections in Adult Patients With Intestinal Failure. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020 Oct;35(5):903-910. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- NanZhu Y, Xin L, Xianghua Y, Jun C, Min L. Risk factors analysis of nosocomial pneumonia in elderly patients with acute cerebral infraction. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Mar;98(13):e15045. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Bernardi M, Angeli P, Claria J, Moreau R, Gines P, Jalan R, et al. Albumin in decompensated cirrhosis: new concepts and perspectives. Gut. 2020 Jun;69(6):1127-1138. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Zohora F, Bidad K, Pourpak Z, Moin M. Biological and Immunological Aspects of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Cancer Development: A Narrative Review. Nutr Cancer. 2018 May-Jun;70(4):546-556. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Wei CC, Zhang ST, Tan G, Zhang SH, Liu M. Impact of anemia on in-hospital complications after ischemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2018 May;25(5):768-774. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Gómez J, Esquinas A, Agudo MD, Sánchez Nieto JM, Núñez ML, Baños V, et al. Retrospective analysis of risk factors and prognosis in non-ventilated patients with nosocomial pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995 Mar;14(3):176-81. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Ewig S, Torres A, El-Ebiary M, Fábregas N, Hernández C, González J, et al. Bacterial colonization patterns in mechanically ventilated patients with traumatic and medical head injury. Incidence, risk factors, and association with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Jan;159(1):188-98. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Lewis RH, Sharpe JP, Swanson JM, Fabian TC, Croce MA, Magnotti LJ. Reinventing the wheel: Impact of prolonged antibiotic exposure on multidrug-resistant ventilator-associated pneumonia in trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018 Aug;85(2):256-262. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Seligman R, Ramos-Lima LF, Oliveira Vdo A, Sanvicente C, Sartori J, Pacheco EF. Risk factors for infection with multidrug-resistant bacteria in non-ventilated patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia. J Bras Pneumol. 2013 May-Jun;39(3):339-48. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Magill SS, O'Leary E, Janelle SJ, Thompson DL, Dumyati G, Nadle J, et al. Changes in Prevalence of Health Care-Associated Infections in U.S. Hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 1;379(18):1732-1744. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Magill SS, O'Leary E, Janelle SJ, Thompson DL, Dumyati G, Nadle J, et al. Changes in Prevalence of Health Care-Associated Infections in U.S. Hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 1;379(18):1732-1744. | CrossRef | PubMed | Di Pasquale M, Aliberti S, Mantero M, Bianchini S, Blasi F. Non-Intensive Care Unit Acquired Pneumonia: A New Clinical Entity? Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Feb 25;17(3):287. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Di Pasquale M, Aliberti S, Mantero M, Bianchini S, Blasi F. Non-Intensive Care Unit Acquired Pneumonia: A New Clinical Entity? Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Feb 25;17(3):287. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63(5):e61-e111. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63(5):e61-e111. | CrossRef | PubMed | Micek ST, Chew B, Hampton N, Kollef MH. A Case-Control Study Assessing the Impact of Nonventilated Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia on Patient Outcomes. Chest. 2016 Nov;150(5):1008-1014. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Micek ST, Chew B, Hampton N, Kollef MH. A Case-Control Study Assessing the Impact of Nonventilated Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia on Patient Outcomes. Chest. 2016 Nov;150(5):1008-1014. | CrossRef | PubMed | Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014 Mar 27;370(13):1198-208. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014 Mar 27;370(13):1198-208. | CrossRef | PubMed | Giuliano KK, Baker D, Quinn B. The epidemiology of nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2018 Mar;46(3):322-327. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Giuliano KK, Baker D, Quinn B. The epidemiology of nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2018 Mar;46(3):322-327. | CrossRef | PubMed | Davis J, Finley D: The breadth of hospital-acquired pneumonía: nonventilated versus ventilated patients in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Patient Safety Advisory. 2012;9(3):99-105. | Link |

Davis J, Finley D: The breadth of hospital-acquired pneumonía: nonventilated versus ventilated patients in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Patient Safety Advisory. 2012;9(3):99-105. | Link | Sopena N, Heras E, Casas I, Bechini J, Guasch I, Pedro-Botet ML, et al. Risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia outside the intensive care unit: a case-control study. Am J Infect Control. 2014 Jan;42(1):38-42. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sopena N, Heras E, Casas I, Bechini J, Guasch I, Pedro-Botet ML, et al. Risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia outside the intensive care unit: a case-control study. Am J Infect Control. 2014 Jan;42(1):38-42. | CrossRef | PubMed | See I, Chang J, Gualandi N, Buser GL, Rohrbach P, Smeltz DA, et al. Clinical Correlates of Surveillance Events Detected by National Healthcare Safety Network Pneumonia and Lower Respiratory Infection Definitions-Pennsylvania, 2011-2012. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Jul;37(7):818-24. | CrossRef | PubMed |

See I, Chang J, Gualandi N, Buser GL, Rohrbach P, Smeltz DA, et al. Clinical Correlates of Surveillance Events Detected by National Healthcare Safety Network Pneumonia and Lower Respiratory Infection Definitions-Pennsylvania, 2011-2012. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Jul;37(7):818-24. | CrossRef | PubMed | Huaman-Junco G. Factores de riesgo asociados a neumonía nosocomial en pacientes adultos. Rev Fac Med Hum. 2019;19(1):80-89. | CrossRef |

Huaman-Junco G. Factores de riesgo asociados a neumonía nosocomial en pacientes adultos. Rev Fac Med Hum. 2019;19(1):80-89. | CrossRef | GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018 Nov 10;392(10159):1789-1858. | CrossRef | PubMed |

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018 Nov 10;392(10159):1789-1858. | CrossRef | PubMed | World Health Organization. Nutritional anaemias: tools for effective prevention and control. WHO [on line]. | Link |

World Health Organization. Nutritional anaemias: tools for effective prevention and control. WHO [on line]. | Link | Koch CG, Li L, Sun Z, Hixson ED, Tang AS, Phillips SC, et al. From Bad to Worse: Anemia on Admission and Hospital-Acquired Anemia. J Patient Saf. 2017 Dec;13(4):211-216. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Koch CG, Li L, Sun Z, Hixson ED, Tang AS, Phillips SC, et al. From Bad to Worse: Anemia on Admission and Hospital-Acquired Anemia. J Patient Saf. 2017 Dec;13(4):211-216. | CrossRef | PubMed | O'Shea E, Trawley S, Manning E, Barrett A, Browne V, Timmons S. Malnutrition in Hospitalised Older Adults: A Multicentre Observational Study of Prevalence, Associations and Outcomes. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(7):830-836. | CrossRef | PubMed |

O'Shea E, Trawley S, Manning E, Barrett A, Browne V, Timmons S. Malnutrition in Hospitalised Older Adults: A Multicentre Observational Study of Prevalence, Associations and Outcomes. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(7):830-836. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bohl DD, Shen MR, Kayupov E, Della Valle CJ. Hypoalbuminemia Independently Predicts Surgical Site Infection, Pneumonia, Length of Stay, and Readmission After Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016 Jan;31(1):15-21. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bohl DD, Shen MR, Kayupov E, Della Valle CJ. Hypoalbuminemia Independently Predicts Surgical Site Infection, Pneumonia, Length of Stay, and Readmission After Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016 Jan;31(1):15-21. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wiedermann CJ. Hypoalbuminemia as Surrogate and Culprit of Infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Apr 26;22(9):4496. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wiedermann CJ. Hypoalbuminemia as Surrogate and Culprit of Infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Apr 26;22(9):4496. | CrossRef | PubMed | Nakano H, Hashimoto H, Mochizuki M, Naraba H, Takahashi Y, Sonoo T, et al. Hypoalbuminemia on Admission as an Independent Risk Factor for Acute Functional Decline after Infection. Nutrients. 2020 Dec 23;13(1):26. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Nakano H, Hashimoto H, Mochizuki M, Naraba H, Takahashi Y, Sonoo T, et al. Hypoalbuminemia on Admission as an Independent Risk Factor for Acute Functional Decline after Infection. Nutrients. 2020 Dec 23;13(1):26. | CrossRef | PubMed | Strassle PD, Sickbert-Bennett EE, Klompas M, Lund JL, Stewart PW, Marx AH, et al. Incidence and risk factors of non-device-associated pneumonia in an acute-care hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020 Jan;41(1):73-79. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Strassle PD, Sickbert-Bennett EE, Klompas M, Lund JL, Stewart PW, Marx AH, et al. Incidence and risk factors of non-device-associated pneumonia in an acute-care hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020 Jan;41(1):73-79. | CrossRef | PubMed | Guzmán-Herrador B, Molina CD, Allam MF, Navajas RF. Independent risk factors associated with hospital-acquired pneumonia in an adult ICU: 4-year prospective cohort study in a university reference hospital. J Public Health (Oxf). 2016 Jun;38(2):378-83. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Guzmán-Herrador B, Molina CD, Allam MF, Navajas RF. Independent risk factors associated with hospital-acquired pneumonia in an adult ICU: 4-year prospective cohort study in a university reference hospital. J Public Health (Oxf). 2016 Jun;38(2):378-83. | CrossRef | PubMed | Xu Y, Lai C, Xu G, Meng W, Zhang J, Hou H,et al. Risk factors of ventilator-associated pneumonia in elderly patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Clin Interv Aging. 2019 Jun 7;14:1027-1038. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Xu Y, Lai C, Xu G, Meng W, Zhang J, Hou H,et al. Risk factors of ventilator-associated pneumonia in elderly patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Clin Interv Aging. 2019 Jun 7;14:1027-1038. | CrossRef | PubMed | Jesus SR, Alves BP, Golin A, Mairin S, Dachi L, Marques A, et al. Association of anemia and malnutrition in hospitalized patients with exclusive enteral nutrition. Nutr Hosp. 2018 Jun 22;35(4):753-760. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Jesus SR, Alves BP, Golin A, Mairin S, Dachi L, Marques A, et al. Association of anemia and malnutrition in hospitalized patients with exclusive enteral nutrition. Nutr Hosp. 2018 Jun 22;35(4):753-760. | CrossRef | PubMed | Organización Mundial de la Salud. Concentraciones de hemoglobina para diagnosticar la anemia y evaluar su gravedad. OMS. [on line]. | Link |

Organización Mundial de la Salud. Concentraciones de hemoglobina para diagnosticar la anemia y evaluar su gravedad. OMS. [on line]. | Link | Parkin DM. 1. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010. Br J Cancer. 2011 Dec 6;105 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S2-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Parkin DM. 1. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010. Br J Cancer. 2011 Dec 6;105 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S2-5. | CrossRef | PubMed | Dziedzic T, Pera J, Klimkowicz A, Turaj W, Slowik A, Rog TM, et al. Serum albumin level and nosocomial pneumonia in stroke patients. Eur J Neurol. 2006 Mar;13(3):299-301. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Dziedzic T, Pera J, Klimkowicz A, Turaj W, Slowik A, Rog TM, et al. Serum albumin level and nosocomial pneumonia in stroke patients. Eur J Neurol. 2006 Mar;13(3):299-301. | CrossRef | PubMed | Hanson LC, Weber DJ, Rutala WA. Risk factors for nosocomial pneumonia in the elderly. Am J Med. 1992 Feb;92(2):161-6. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hanson LC, Weber DJ, Rutala WA. Risk factors for nosocomial pneumonia in the elderly. Am J Med. 1992 Feb;92(2):161-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | Yang J, Sun H, Wan S, Mamtawla G, Gao X, Zhang L, et al. Prolonged Parenteral Nutrition Is One of the Most Significant Risk Factors for Nosocomial Infections in Adult Patients With Intestinal Failure. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020 Oct;35(5):903-910. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Yang J, Sun H, Wan S, Mamtawla G, Gao X, Zhang L, et al. Prolonged Parenteral Nutrition Is One of the Most Significant Risk Factors for Nosocomial Infections in Adult Patients With Intestinal Failure. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020 Oct;35(5):903-910. | CrossRef | PubMed | NanZhu Y, Xin L, Xianghua Y, Jun C, Min L. Risk factors analysis of nosocomial pneumonia in elderly patients with acute cerebral infraction. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Mar;98(13):e15045. | CrossRef | PubMed |

NanZhu Y, Xin L, Xianghua Y, Jun C, Min L. Risk factors analysis of nosocomial pneumonia in elderly patients with acute cerebral infraction. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Mar;98(13):e15045. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bernardi M, Angeli P, Claria J, Moreau R, Gines P, Jalan R, et al. Albumin in decompensated cirrhosis: new concepts and perspectives. Gut. 2020 Jun;69(6):1127-1138. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bernardi M, Angeli P, Claria J, Moreau R, Gines P, Jalan R, et al. Albumin in decompensated cirrhosis: new concepts and perspectives. Gut. 2020 Jun;69(6):1127-1138. | CrossRef | PubMed | Zohora F, Bidad K, Pourpak Z, Moin M. Biological and Immunological Aspects of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Cancer Development: A Narrative Review. Nutr Cancer. 2018 May-Jun;70(4):546-556. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Zohora F, Bidad K, Pourpak Z, Moin M. Biological and Immunological Aspects of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Cancer Development: A Narrative Review. Nutr Cancer. 2018 May-Jun;70(4):546-556. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wei CC, Zhang ST, Tan G, Zhang SH, Liu M. Impact of anemia on in-hospital complications after ischemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2018 May;25(5):768-774. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wei CC, Zhang ST, Tan G, Zhang SH, Liu M. Impact of anemia on in-hospital complications after ischemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2018 May;25(5):768-774. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gómez J, Esquinas A, Agudo MD, Sánchez Nieto JM, Núñez ML, Baños V, et al. Retrospective analysis of risk factors and prognosis in non-ventilated patients with nosocomial pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995 Mar;14(3):176-81. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gómez J, Esquinas A, Agudo MD, Sánchez Nieto JM, Núñez ML, Baños V, et al. Retrospective analysis of risk factors and prognosis in non-ventilated patients with nosocomial pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995 Mar;14(3):176-81. | CrossRef | PubMed | Ewig S, Torres A, El-Ebiary M, Fábregas N, Hernández C, González J, et al. Bacterial colonization patterns in mechanically ventilated patients with traumatic and medical head injury. Incidence, risk factors, and association with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Jan;159(1):188-98. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ewig S, Torres A, El-Ebiary M, Fábregas N, Hernández C, González J, et al. Bacterial colonization patterns in mechanically ventilated patients with traumatic and medical head injury. Incidence, risk factors, and association with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Jan;159(1):188-98. | CrossRef | PubMed |Systematization of initiatives in sexual and reproductive health about good practices criteria in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in primary health care in Chile

Clinical, psychological, social, and family characterization of suicidal behavior in Chilean adolescents: a multiple correspondence analysis