Key Words: pregnancy, COVID-19, socioeconomic factors

Resumen

Objetivo

Describir las características clínicas y factores sociodemográficos asociados a COVID-19 en gestantes de un hospital materno infantil de Lima, Perú.

Método

Estudio cuantitativo observacional. La población estuvo compuesta por gestantes atendidas en la unidad de emergencia, con la prueba para el diagnóstico de COVID-19. A las madres se les valoró edad, edad gestacional, lugar de procedencia, ocupación, nivel de estudios, estado civil, número de hijos, índice de masa corporal previa, índice de masa corporal de la gestación, vacuna antitetánica, controles prenatales, y hemoglobina. Después de un análisis bivariado se aplicó un modelo de regresión lineal generalizado.

Resultados

Incluimos a 200 mujeres, con edades de 18 a 34 años (84,5%). Más de la mitad procedía de Lima (52,5%), 79% tenía como ocupación el ser ama de casa, 71,9% alcanzó estudios secundarios y 60% registró estado civil de conviviente. La incidencia de COVID-19 fue de 31,5% mediante pruebas rápidas. La mediana de edad gestacional al momento de la evaluación para COVID-19 fue de 36 semanas. El índice de masa corporal pregestacional, comparado entre las gestantes con COVID-19 y las que no lo tuvieron, fue normal en 36,7 y 63,3%. Se detectó sobrepeso en 38,1 y 61,9% de las pacientes, obesidad en 30,3 y 69,7%, respectivamente. Los niveles de hemoglobina superiores o iguales a 11 gramos por decilitro se reportaron en 39,7 y 60,3% en cada grupo; hemoglobina entre 10 y 10,9 gramos por decilitro, en 21,2 y 78,8%; y hemoglobina entre 7 y 9,9 gramos por decilitro, en 20 y 80%, respectivamente. La razón de prevalencia con un intervalo de confianza al 95%, identificó al estado civil conviviente asociado a menor riesgo de tener COVID-19 en gestantes (razón de prevalencia: 0,41, valor p < 0,001).

Conclusión

Las gestantes cuyo estado civil fue de conviviente presentaron menor riesgo de experimentar COVID-19. Es necesario seguir estudiando los factores que se asocian a la presencia de COVID-19 en gestantes, así como posibles factores sociodemográficos o económicos detrás del estado civil conviviente.

|

Main messages

|

Introduction

The physiological and mechanical changes associated with pregnancy increase the likelihood of mother and child infection. A large study of women with COVID-19 found that disease manifestations are usually mild [1], and it has been reported that many pregnant women are asymptomatic [2]. However, other pandemics have shown that pregnant women have been more prone to these infections, such as influenza in 1918 [3] and the H1N1 influenza epidemic in 2009 [4].

The most frequent symptoms of pregnant women with COVID-19 are cough and fever [5],[6],[7]. Other findings include lymphocytopenia, elevated C-reactive protein, and almost 91% of the women gave birth by cesarean section [8]. Cesarean section has been associated with preterm birth, decreased Apgar score at birth, and pneumonia, among others [9].

The severity of disease and death from COVID-19 may be conditioned by risk factors such as obesity (body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2), diabetes, maternal age over 40 years [10], and cardiovascular disease [11]. These factors may lead to an increased risk of miscarriage, prematurity, and fetal growth restriction. A systematic review of case reports and case series mentions that some COVID-19 positive mothers had severe maternal morbidity and/or perinatal death, although most were discharged without any complications [8].

There is still limited research on the factors associated with COVID-19 infection in the general population; nor is it certain that the associations identified can be applied to pregnant women. Moreover, clinical variables are not the only ones implicated in gestational morbidity and mortality outcomes. Studies in Latin America have linked economic support [12] and education to COVID-19 [13]. Other studies that have included sociodemographic variables have associated religion with better perinatal outcomes [14]. A study in Iran with COVID-19 positive pregnant women applied the adjusted general linear model and found that satisfaction with marital life, high educational level, and high income can improve the mental health of pregnant women [15].

Pregnant women may face a higher risk of infection due to their adaptation and the immunosuppressive state of pregnancy. SARS-CoV-2 infection can place women and their children at risk [16],[17]. In this sense, we consider it essential to identify the factors related to COVID-19 in pregnant women to prevent modifiable factors and reduce the probability of such infection. We also know that there is still no proven treatment for mothers, fetuses, or newborns. In this sense, we set out to determine the clinical characteristics and sociodemographic factors associated with COVID-19 in pregnant women in a public maternity ward and a children's hospital in Lima, Peru, between 2020 and 2021.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study presents a quantitative, analytical, cross-sectional, and exploratory design. The population comprises pregnant mothers who attended the emergency service of the Hospital Nacional Docente Madre Niño San Bartolomé from June 2020 to January 2021. The sample is made up of the total study population. Due to the pandemic, the hospital only received pregnant women through the emergency service. These women were attended by the medical and obstetrical staff, underwent a physical examination, laboratory tests, and were subjected to a rapid test (PRIMA Lab SA) to detect IgM and/or IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. The test was taken at the point of care. If necessary, patients were referred to another hospital to complement the study with molecular tests to detect SARS-CoV-2 carriers [18],[19] or to assess further patients presenting positive IgM. All emergency care data were recorded in the medical history record by the staff in charge.

Clinical records and/or the nursing emergency record book of pregnancies with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 were reviewed. Information on sociodemographic and biochemical data was obtained from the clinical records. The dependent variable was being positive or not for COVID-19. The covariates included were age, gestational age, place of origin, occupation, educational level, marital status, number of children, previous body mass index, gestational body mass index, prenatal controls, hemoglobin, and COVID-19 symptoms.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed, obtaining frequency measures for categorical variables and central tendency and dispersion parameters for numerical variables according to the data distribution. Hypothesis testing was performed through a Chi-square test. Subsequently, a generalized linear Poisson family model and log function developed an association analysis with bivariate regression for each potentially associated factor, in addition to a multiple regression that included all the potential associated variables. The 95% confidence interval was used, and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No confounding or interaction variables were identified during the statistical analysis. The statistical package used was STATA V17.0 (StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statis- tical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

Results

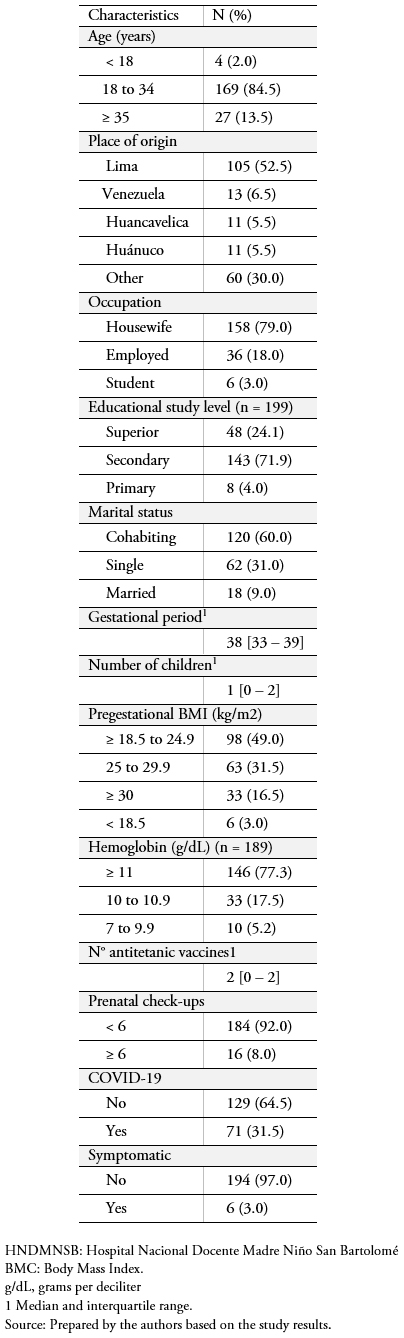

Data from 200 pregnant women who attended emergency care at a maternity center in Lima were evaluated. A total of 31.5% (71) were positive for the COVID-19 rapid test. Table 1 shows the mother's characteristics. Eighty-four percent of the women were between 18 and 34 years old. Fifty-two percent lived in Lima, 79% worked as housewives, 71.9% had a secondary school education, and 60% cohabitated. Pregestational body mass index assessment showed that almost half had normal weight, 36.1% were overweight, and 1.5% were obese. We also found that 77.3% had hemoglobin greater than or equal to 11 g/dL and that the majority (97%) were asymptomatic.

Table 1. General characteristics of pregnant women attended in the HDMNSB.

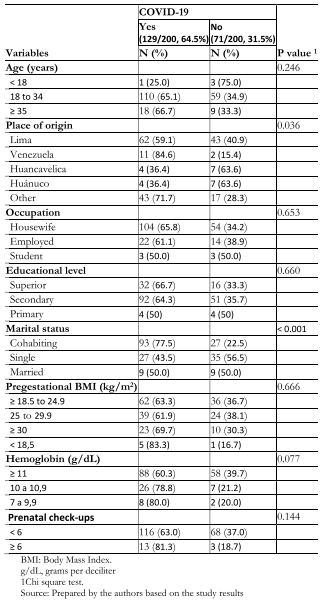

Table 2 shows the hypothesis test, where the place of origin and marital status shows a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the two study groups.

Table 2. Factors associated with the diagnosis of COVID-19 through a Chi-square bivariate analysis.

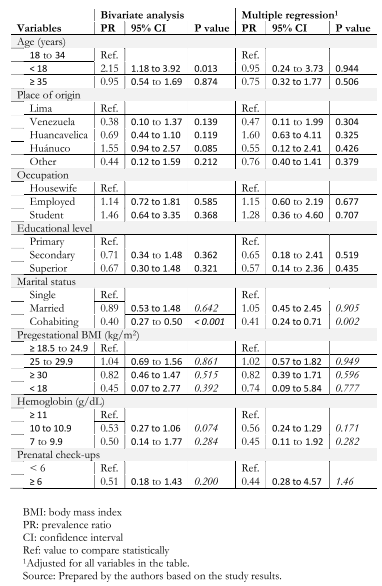

Table 3 shows a bivariate regression analysis, identifying a significantly higher prevalence of COVID-19 among patients under 18 years and in cohabitant pregnant women.

In multiple regression analysis, cohabiting marital status was associated with a higher incidence of COVID-19 cases (prevalence ratio: 0.41; 95% confidence interval: 0.24 to 0.71), the only variable that independently linked COVID-19 with the pregnant women.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The findings of this study show that pregnant women in a hospital in Lima with a diagnosis of COVID-19 had cohabiting marital status as an associated factor.

Many studies have evaluated pregnant women with COVID-19 who presented in labor or near term. Of these, very few cases have been reported before 36 weeks of gestation. No studies have directly examined the association between COVID-19 and early pregnancy [20],[21],[22]. The gestational age was similar to other studies, ranging from 30 to 42 weeks and a median of 36 weeks at the time of evaluation for COVID-19. Zhang et al. report that having COVID-19 during the first weeks of gestation is no more severe than among women who are not pregnant [23].

A systematic review identified preexisting comorbidities, increased maternal age, and elevated body mass index as risk factors for severe COVID-19 in pregnant women [21]. The database used for our study does not include the comorbidities, but it includes maternal age, hemoglobin level, and body mass index. However, after statistical analysis, these variables were not associated with the presence of COVID-19. The same systematic review describes that preterm birth rates are significantly higher in pregnant women with COVID-19 than in pregnant women without the disease [21]. Our study did not assess birth outcomes, as emergency care did not necessarily imply these when assessing the presence of COVID-19.

A study from the United Kingdom describes that of the COVID-19 positive pregnant women admitted to the hospital, 69% were overweight or obese, and 41% were older than 35 years [22]. In our study in Peru, 48% were overweight and obese, and only 13.5% had maternal age over 35 years, so our findings were much lower than those of the United Kingdom. In Spain, the median maternal age of COVID-19 positive pregnant women was 34.6 years [24]. However, a study in Kuwait with positive pregnant women had a median age of 31 years and a mean gestational age of 29 weeks [25].

A retrospective study in Chicago (United States) compared sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in pregnant women with and without coronavirus. The group that resulted positive for COVID-19 was younger, with higher BMI, a higher prevalence of African Americans and Latinos, and children (p < 0.05). Another sociodemographic variable was being single [26]. We believe that having identified cohabiting marital status as a variable associated with COVID-19 in pregnant women is related to the Chicago study since cohabiting is the opposite of being single, hence, its protective role. This finding provides knowledge about risk factors. However, it is necessary to understand why cohabitation (as opposed to being married or single) decreases the risk of having COVID-19. Therefore, it is necessary to develop studies with more representative samples of the pregnant and general populations, assuming that there may be variables behind marital status, such as economic, living environment [27], or cultural variables, among others.

The main limitation of our study lies in the retrospective design, obtaining data from secondary sources such as the clinical history, emergency record book, and prenatal control cards. However, although our clinical data recording did not contemplate research purposes (affecting in this way the rigor and standardization of data collection), the biological vulnerability of pregnancy tends to produce a greater predisposition for care in the health personnel, the pregnant woman and her family, as well as a better information recall needed from the pregnant woman.

Conclusions

Pregnant women with cohabiting marital status have a lower risk of becoming ill with COVID-19. This protective factor does not dismiss the early need to monitor and identify pregnant women to provide timely health care in the event of probable COVID-19 infection.

We believe that further studies are needed to explore the sociodemographic factors behind the cohabiting marital status variable. Further studies in pregnant women are also needed to understand other possible associated factors.

Pregnant women may face a higher risk of infection due to the adaptation and immunosuppressive state of pregnancy. Coping with SARS-CoV-2 may place women and their children at risk.

Notes

Contributor roles

YR, PC, ML: conceptualization, methodology, PC: formal analysis, data curation, ML PC: analysis, writing, revision, editing, visualization, YR, PC, ML: approved the final version and accepted responsibility for the content of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Language of submission

English

Ethics

The study was approved in February 2021 by the Ethics Committee of the Norbert Wiener University, Exp. No. 396-2021.

Data availability statement

The database can be made available on request.

Table 1. General characteristics of pregnant women attended in the HDMNSB.

Table 1. General characteristics of pregnant women attended in the HDMNSB.

Table 2. Factors associated with the diagnosis of COVID-19 through a Chi-square bivariate analysis.

Table 2. Factors associated with the diagnosis of COVID-19 through a Chi-square bivariate analysis.

Table 3. Factors independently bassociated with the diagnosis of COVID-19 in multiple regression analysis with a generalized linear model (GLM).

Table 3. Factors independently bassociated with the diagnosis of COVID-19 in multiple regression analysis with a generalized linear model (GLM).

Objetivo

Describir las características clínicas y factores sociodemográficos asociados a COVID-19 en gestantes de un hospital materno infantil de Lima, Perú.

Método

Estudio cuantitativo observacional. La población estuvo compuesta por gestantes atendidas en la unidad de emergencia, con la prueba para el diagnóstico de COVID-19. A las madres se les valoró edad, edad gestacional, lugar de procedencia, ocupación, nivel de estudios, estado civil, número de hijos, índice de masa corporal previa, índice de masa corporal de la gestación, vacuna antitetánica, controles prenatales, y hemoglobina. Después de un análisis bivariado se aplicó un modelo de regresión lineal generalizado.

Resultados

Incluimos a 200 mujeres, con edades de 18 a 34 años (84,5%). Más de la mitad procedía de Lima (52,5%), 79% tenía como ocupación el ser ama de casa, 71,9% alcanzó estudios secundarios y 60% registró estado civil de conviviente. La incidencia de COVID-19 fue de 31,5% mediante pruebas rápidas. La mediana de edad gestacional al momento de la evaluación para COVID-19 fue de 36 semanas. El índice de masa corporal pregestacional, comparado entre las gestantes con COVID-19 y las que no lo tuvieron, fue normal en 36,7 y 63,3%. Se detectó sobrepeso en 38,1 y 61,9% de las pacientes, obesidad en 30,3 y 69,7%, respectivamente. Los niveles de hemoglobina superiores o iguales a 11 gramos por decilitro se reportaron en 39,7 y 60,3% en cada grupo; hemoglobina entre 10 y 10,9 gramos por decilitro, en 21,2 y 78,8%; y hemoglobina entre 7 y 9,9 gramos por decilitro, en 20 y 80%, respectivamente. La razón de prevalencia con un intervalo de confianza al 95%, identificó al estado civil conviviente asociado a menor riesgo de tener COVID-19 en gestantes (razón de prevalencia: 0,41, valor p < 0,001).

Conclusión

Las gestantes cuyo estado civil fue de conviviente presentaron menor riesgo de experimentar COVID-19. Es necesario seguir estudiando los factores que se asocian a la presencia de COVID-19 en gestantes, así como posibles factores sociodemográficos o económicos detrás del estado civil conviviente.

Authors:

Yda Rodriguez Huaman[1], Pavel J Contreras[2], Michelle Lozada-Urbano[3]

Authors:

Yda Rodriguez Huaman[1], Pavel J Contreras[2], Michelle Lozada-Urbano[3]

Affiliation:

[1] Escuela de Obstetricia, Universidad Norbert Wiener, Lima, Perú

[2] Escuela de Medicina, Universidad Norbert Wiener, Lima, Perú

[3] South American Center for Education and Research in Public Health. Universidad Norbert Wiener, Lima, Perú

E-mail: michelle.lozada@uwiener.edu.pe

Author address:

[1] Av. Arequipa # 444, Cercado de Lima, Lima, 15046, Perú

Citation: Rodriguez Huaman Y, Contreras PJ, Lozada-Urbano M. Clinical characteristics and sociodemographic factors associated with COVID-19 infection in pregnant women in a maternal and children's public hospital. Medwave 2021;21(7):e8442 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2021.07.8442

Submission date: 20/3/2021

Acceptance date: 5/7/2021

Publication date: 23/8/2021

Origin: Externally peer-reviewed by three reviewers, double-blind

Type of review: Not commissioned

Comments (0)

We are pleased to have your comment on one of our articles. Your comment will be published as soon as it is posted. However, Medwave reserves the right to remove it later if the editors consider your comment to be: offensive in some sense, irrelevant, trivial, contains grammatical mistakes, contains political harangues, appears to be advertising, contains data from a particular person or suggests the need for changes in practice in terms of diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic interventions, if that evidence has not previously been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No comments on this article.

To comment please log in

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics.

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics. There may be a 48-hour delay for most recent metrics to be posted.

- Vivanti AJ, Vauloup-Fellous C, Prevot S, Zupan V, Suffee C, Do Cao J, et al. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2020 Jul 14;11(1):3572. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Boushra MN, Koyfman A, Long B. COVID-19 in pregnancy and the puerperium: A review for emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Feb;40:193-198. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Gottfredsson M. Spaenska veikin á Islandi 1918. Laerdómur í laeknisfraedi og sögu [The Spanish flu in Iceland 1918. Lessons in medicine and history]. Laeknabladid. 2008 Nov;94(11):737-45. Icelandic. | PubMed |

- Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Williams JL, Swerdlow DL, Biggerstaff MS, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009 Aug 8;374(9688):451-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Juan J, Gil MM, Rong Z, Zhang Y, Yang H, Poon LC. Effect of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcome: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jul;56(1):15-27. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Boushra MN, Koyfman A, Long B. COVID-19 in pregnancy and the puerperium: A review for emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Feb;40:193-198. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Jafari M, Pormohammad A, Sheikh Neshin SA, Ghorbani S, Bose D, Alimohammadi S, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 and comparison with control patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2021 Jan 2:e2208. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Zaigham M, Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: A systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020 Jul;99(7):823-829. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Chen YH, Keller J, Wang IT, Lin CC, Lin HC. Pneumonia and pregnancy outcomes: a nationwide population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;207(4):288.e1-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, Villamizar-Peña R, Holguin-Rivera Y, Escalera-Antezana JP, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 Mar-Apr;34:101623. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Czeresnia RM, Trad ATA, Britto ISW, Negrini R, Nomura ML, Pires P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and Pregnancy: A Review of the Facts. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2020 Sep;42(9):562-568. English. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Malangón SZ. Factores asociados a la asistencia al control prenatal en gestantes del municipio de Yopal Casanare, Colombia (Tesis). Bogotá-Colombia: Universidad del Rosario. 2015. [10 de mayo de 2018]. [On line] | Link |

- Lebso M, Anato A, Loha E. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in Southern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017 Dec 11;12(12):e0188783. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Patil CL, Klima CS, Leshabari SC, Steffen AD, Pauls H, McGown M, et al. Randomized controlled pilot of a group antenatal care model and the sociodemographic factors associated with pregnancy-related empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017 Nov 8;17(Suppl 2):336. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Effati-Daryani F, Zarei S, Mohammadi A, Hemmati E, Ghasemi Yngyknd S, Mirghafourvand M. Depression, stress, anxiety and their predictors in Iranian pregnant women during the outbreak of COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 2020 Sep 22;8(1):99. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Chen R, Chen J, Meng QT. Chest computed tomography images of early coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Can J Anaesth. 2020 Jun;67(6):754-755. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Mor G, Cardenas I, Abrahams V, Guller S. Inflammation and pregnancy: the role of the immune system at the implantation site. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 Mar;1221(1):80-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Canetti D, Dell'Acqua R, Riccardi N, Della Torre L, Bigoloni A, Muccini C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test as a Diagnostic Tool in Hospitalized Patients and Healthcare Workers, at a large Teaching Hospital in northern Italy, during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. New Microbiol. 2020 Oct;43(4):161-165. Epub 2020 Oct 31. | PubMed |

- Wu JL, Tseng WP, Lin CH, Lee TF, Chung MY, Huang CH, et al. Four point-of-care lateral flow immunoassays for diagnosis of COVID-19 and for assessing dynamics of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. 2020 Sep;81(3):435-442. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Segars J, Katler Q, McQueen DB, Kotlyar A, Glenn T, Knight Z, Feinberg EC, et al. Prior and novel coronaviruses, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), and human reproduction: what is known? Fertil Steril. 2020 Jun;113(6):1140-1149. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, Yap M, Chatterjee S, Kew T, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020 Sep 1;370:m3320. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Knight M, Bunch K, Vousden N, Morris E, Simpson N, Gale C, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK: national population based cohort study. BMJ. 2020 Jun 8;369:m2107. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Zhang L, Jiang Y, Wei M, Cheng BH, Zhou XC, Li J, et al. [Analysis of the pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19 in Hubei Province]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2020 Mar 25;55(3):166-171. Chinese. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Cuñarro-López Y, Pintado-Recarte P, Cueto-Hernández I, Hernández-Martín C, Payá-Martínez MP, Muñóz-Chápuli MDM, et al. The Profile of the Obstetric Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection According to Country of Origin of the Publication: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Clin Med. 2021 Jan 19;10(2):360. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Ayed A, Embaireeg A, Benawadh A, Al-Fouzan W, Hammoud M, Al-Hathal M, et al. Maternal and perinatal characteristics and outcomes of pregnancies complicated with COVID-19 in Kuwait. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Dec 2;20(1):754. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Sakowicz A, Ayala AE, Ukeje CC, Witting CS, Grobman WA, Miller ES. Risk factors for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 Nov;2(4):100198. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Vigod SN, Wilson CA, Howard LM. Depression in pregnancy. BMJ. 2016 Mar 24;352:i1547. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Vivanti AJ, Vauloup-Fellous C, Prevot S, Zupan V, Suffee C, Do Cao J, et al. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2020 Jul 14;11(1):3572. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Vivanti AJ, Vauloup-Fellous C, Prevot S, Zupan V, Suffee C, Do Cao J, et al. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2020 Jul 14;11(1):3572. | CrossRef | PubMed | Boushra MN, Koyfman A, Long B. COVID-19 in pregnancy and the puerperium: A review for emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Feb;40:193-198. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Boushra MN, Koyfman A, Long B. COVID-19 in pregnancy and the puerperium: A review for emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Feb;40:193-198. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gottfredsson M. Spaenska veikin á Islandi 1918. Laerdómur í laeknisfraedi og sögu [The Spanish flu in Iceland 1918. Lessons in medicine and history]. Laeknabladid. 2008 Nov;94(11):737-45. Icelandic. | PubMed |

Gottfredsson M. Spaenska veikin á Islandi 1918. Laerdómur í laeknisfraedi og sögu [The Spanish flu in Iceland 1918. Lessons in medicine and history]. Laeknabladid. 2008 Nov;94(11):737-45. Icelandic. | PubMed | Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Williams JL, Swerdlow DL, Biggerstaff MS, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009 Aug 8;374(9688):451-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Williams JL, Swerdlow DL, Biggerstaff MS, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009 Aug 8;374(9688):451-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Juan J, Gil MM, Rong Z, Zhang Y, Yang H, Poon LC. Effect of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcome: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jul;56(1):15-27. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Juan J, Gil MM, Rong Z, Zhang Y, Yang H, Poon LC. Effect of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcome: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jul;56(1):15-27. | CrossRef | PubMed | Boushra MN, Koyfman A, Long B. COVID-19 in pregnancy and the puerperium: A review for emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Feb;40:193-198. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Boushra MN, Koyfman A, Long B. COVID-19 in pregnancy and the puerperium: A review for emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Feb;40:193-198. | CrossRef | PubMed | Jafari M, Pormohammad A, Sheikh Neshin SA, Ghorbani S, Bose D, Alimohammadi S, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 and comparison with control patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2021 Jan 2:e2208. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Jafari M, Pormohammad A, Sheikh Neshin SA, Ghorbani S, Bose D, Alimohammadi S, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 and comparison with control patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2021 Jan 2:e2208. | CrossRef | PubMed | Zaigham M, Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: A systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020 Jul;99(7):823-829. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Zaigham M, Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: A systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020 Jul;99(7):823-829. | CrossRef | PubMed | Chen YH, Keller J, Wang IT, Lin CC, Lin HC. Pneumonia and pregnancy outcomes: a nationwide population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;207(4):288.e1-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Chen YH, Keller J, Wang IT, Lin CC, Lin HC. Pneumonia and pregnancy outcomes: a nationwide population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;207(4):288.e1-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, Villamizar-Peña R, Holguin-Rivera Y, Escalera-Antezana JP, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 Mar-Apr;34:101623. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, Villamizar-Peña R, Holguin-Rivera Y, Escalera-Antezana JP, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 Mar-Apr;34:101623. | CrossRef | PubMed | Czeresnia RM, Trad ATA, Britto ISW, Negrini R, Nomura ML, Pires P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and Pregnancy: A Review of the Facts. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2020 Sep;42(9):562-568. English. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Czeresnia RM, Trad ATA, Britto ISW, Negrini R, Nomura ML, Pires P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and Pregnancy: A Review of the Facts. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2020 Sep;42(9):562-568. English. | CrossRef | PubMed | Malangón SZ. Factores asociados a la asistencia al control prenatal en gestantes del municipio de Yopal Casanare, Colombia (Tesis). Bogotá-Colombia: Universidad del Rosario. 2015. [10 de mayo de 2018]. [On line] | Link |

Malangón SZ. Factores asociados a la asistencia al control prenatal en gestantes del municipio de Yopal Casanare, Colombia (Tesis). Bogotá-Colombia: Universidad del Rosario. 2015. [10 de mayo de 2018]. [On line] | Link | Lebso M, Anato A, Loha E. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in Southern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017 Dec 11;12(12):e0188783. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Lebso M, Anato A, Loha E. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in Southern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017 Dec 11;12(12):e0188783. | CrossRef | PubMed | Patil CL, Klima CS, Leshabari SC, Steffen AD, Pauls H, McGown M, et al. Randomized controlled pilot of a group antenatal care model and the sociodemographic factors associated with pregnancy-related empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017 Nov 8;17(Suppl 2):336. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Patil CL, Klima CS, Leshabari SC, Steffen AD, Pauls H, McGown M, et al. Randomized controlled pilot of a group antenatal care model and the sociodemographic factors associated with pregnancy-related empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017 Nov 8;17(Suppl 2):336. | CrossRef | PubMed | Effati-Daryani F, Zarei S, Mohammadi A, Hemmati E, Ghasemi Yngyknd S, Mirghafourvand M. Depression, stress, anxiety and their predictors in Iranian pregnant women during the outbreak of COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 2020 Sep 22;8(1):99. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Effati-Daryani F, Zarei S, Mohammadi A, Hemmati E, Ghasemi Yngyknd S, Mirghafourvand M. Depression, stress, anxiety and their predictors in Iranian pregnant women during the outbreak of COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 2020 Sep 22;8(1):99. | CrossRef | PubMed | Chen R, Chen J, Meng QT. Chest computed tomography images of early coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Can J Anaesth. 2020 Jun;67(6):754-755. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Chen R, Chen J, Meng QT. Chest computed tomography images of early coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Can J Anaesth. 2020 Jun;67(6):754-755. | CrossRef | PubMed | Mor G, Cardenas I, Abrahams V, Guller S. Inflammation and pregnancy: the role of the immune system at the implantation site. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 Mar;1221(1):80-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Mor G, Cardenas I, Abrahams V, Guller S. Inflammation and pregnancy: the role of the immune system at the implantation site. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 Mar;1221(1):80-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Canetti D, Dell'Acqua R, Riccardi N, Della Torre L, Bigoloni A, Muccini C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test as a Diagnostic Tool in Hospitalized Patients and Healthcare Workers, at a large Teaching Hospital in northern Italy, during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. New Microbiol. 2020 Oct;43(4):161-165. Epub 2020 Oct 31. | PubMed |

Canetti D, Dell'Acqua R, Riccardi N, Della Torre L, Bigoloni A, Muccini C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test as a Diagnostic Tool in Hospitalized Patients and Healthcare Workers, at a large Teaching Hospital in northern Italy, during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. New Microbiol. 2020 Oct;43(4):161-165. Epub 2020 Oct 31. | PubMed | Wu JL, Tseng WP, Lin CH, Lee TF, Chung MY, Huang CH, et al. Four point-of-care lateral flow immunoassays for diagnosis of COVID-19 and for assessing dynamics of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. 2020 Sep;81(3):435-442. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wu JL, Tseng WP, Lin CH, Lee TF, Chung MY, Huang CH, et al. Four point-of-care lateral flow immunoassays for diagnosis of COVID-19 and for assessing dynamics of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. 2020 Sep;81(3):435-442. | CrossRef | PubMed | Segars J, Katler Q, McQueen DB, Kotlyar A, Glenn T, Knight Z, Feinberg EC, et al. Prior and novel coronaviruses, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), and human reproduction: what is known? Fertil Steril. 2020 Jun;113(6):1140-1149. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Segars J, Katler Q, McQueen DB, Kotlyar A, Glenn T, Knight Z, Feinberg EC, et al. Prior and novel coronaviruses, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), and human reproduction: what is known? Fertil Steril. 2020 Jun;113(6):1140-1149. | CrossRef | PubMed | Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, Yap M, Chatterjee S, Kew T, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020 Sep 1;370:m3320. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, Yap M, Chatterjee S, Kew T, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020 Sep 1;370:m3320. | CrossRef | PubMed | Knight M, Bunch K, Vousden N, Morris E, Simpson N, Gale C, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK: national population based cohort study. BMJ. 2020 Jun 8;369:m2107. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Knight M, Bunch K, Vousden N, Morris E, Simpson N, Gale C, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK: national population based cohort study. BMJ. 2020 Jun 8;369:m2107. | CrossRef | PubMed | Zhang L, Jiang Y, Wei M, Cheng BH, Zhou XC, Li J, et al. [Analysis of the pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19 in Hubei Province]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2020 Mar 25;55(3):166-171. Chinese. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Zhang L, Jiang Y, Wei M, Cheng BH, Zhou XC, Li J, et al. [Analysis of the pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19 in Hubei Province]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2020 Mar 25;55(3):166-171. Chinese. | CrossRef | PubMed | Cuñarro-López Y, Pintado-Recarte P, Cueto-Hernández I, Hernández-Martín C, Payá-Martínez MP, Muñóz-Chápuli MDM, et al. The Profile of the Obstetric Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection According to Country of Origin of the Publication: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Clin Med. 2021 Jan 19;10(2):360. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Cuñarro-López Y, Pintado-Recarte P, Cueto-Hernández I, Hernández-Martín C, Payá-Martínez MP, Muñóz-Chápuli MDM, et al. The Profile of the Obstetric Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection According to Country of Origin of the Publication: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Clin Med. 2021 Jan 19;10(2):360. | CrossRef | PubMed | Ayed A, Embaireeg A, Benawadh A, Al-Fouzan W, Hammoud M, Al-Hathal M, et al. Maternal and perinatal characteristics and outcomes of pregnancies complicated with COVID-19 in Kuwait. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Dec 2;20(1):754. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ayed A, Embaireeg A, Benawadh A, Al-Fouzan W, Hammoud M, Al-Hathal M, et al. Maternal and perinatal characteristics and outcomes of pregnancies complicated with COVID-19 in Kuwait. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Dec 2;20(1):754. | CrossRef | PubMed |Systematization of initiatives in sexual and reproductive health about good practices criteria in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in primary health care in Chile

Clinical, psychological, social, and family characterization of suicidal behavior in Chilean adolescents: a multiple correspondence analysis