Key Words: teratoma, sacrococcygeal region, newborn infant

Abstract

We present a male newborn child with a sacrococcygeal mass who was sent to clinic 46 of the Mexican Social Security Institute located in Gomez Palacio, Durango, Mexico for pediatric/neonatal surgical resolution. The mass was detected on gestation week 24 in the sacrococcygeal area and was initially interpreted as a myelomeningocele. On gestation week 32, the mass had grown, so the diagnosis of cystic hygroma was posed. The child was born at 38 weeks of gestational age with a large tumor in the sacrococcygeal area. Images were obtained, and tumor resection was performed without complications. Pathologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of sacrococcygeal teratoma. The postoperative course was uneventful and there were no further complications.

Introduction

Sacrococcygeal teratoma is a neoplasia which despite its low frequency, is one of the most common ones in neonates [1]. Unlike in adults, fetal teratomas mostly develop at sacrococcygeal level. They are formed of various types of tissue derived from at least two, or the three embryonic layers [2]. These tumors may get enormous dimensions and contain large blood vessels that provoke blood depriving to the developing fetus.

The best way to treat this malignancy, is through complete resection and a histopathological study of it. With this approach it is possible to prevent late complications such as coagulopathy, necrosis by compression, infections or intratumoral hemorrhage [3].

The differential diagnosis must be made with the myelomeningocele - entity that more frequently leads to confusion with other diseases such as lipomas, hemangiomas, pilonidal cyst and epidermoid cyst. Furthermore, the teratoma must be differentiated according to its location, between the coccyx and the anus, from others that are located behind the sacrum and even in the intrapelvic region [4].

The availability of obstetric ultrasound has been a great breakthrough that has allowed the prenatal diagnosis of many of these lesions. With it, timely planning, study and multidisciplinary treatment of patients can be achieved [5], as summarized in the case presented below.

Presentation of the case

Male newborn, 18 year old mother. Product of gestation: 1. A Rh positive blood type. Normal evolution of pregnancy, prenatal care from the beginning, attended eleven medical consultations. Presence of tumor mass in sacrococcygeal region was detected by ultrasound since 24 weeks of pregnancy. At first it was categorized as probable myelomeningocele, consequently, the patient was sent for perinatal handling to the third level of care at clinic 16 of the Mexican Social Security Institute in Torreón Coahuila, Mexico. A control ultrasound was performed at 32 weeks of pregnancy in which tumor volume increased with a probable diagnosis of cystic hygroma. It was scheduled for cesarean section at 38 weeks of gestation and a single live male product is obtained, with Apgar 8-9, Silverman Anderson 0, Capurro test : 38 weeks of gestation, weight 4500 g.

Physical examination: normal head; cardiopulmonary system not involved; soft, depressible abdomen, without organ enlargement. One tumor with about 1 kg of weight, 16.5x8.5x12 cm dimensions and liquid appearance in approximately 50% of its size can be appreciated in the sacrococcygeal region. (Figure 1)

A simple and contrasted axial computerized tomography of pelvis is performed. A proper aligned complete lumbosacral spine is observed in the tomography. The bone structure of the pelvis has no alterations. Bladder with little repletion and unaltered. Distal rectum with anterior orientation. Suggestive image of anal opening can be seen in previous perianal region. Testicles and penis with no alterations. Soft tissues in perianal region show cystic aspect in a large image with 16.5 cm of transversal diameter by 8.5 cm anteroposterior and 12 cm longitudinal, with presence of three calcium images on its wall.

Through the administration of contrasting agent, reinforcement of the wall is observed, as well as a thin septum in its posterior wall (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2 A and B. Contrast enhanced computerized axial tomography scan

More images can be observed at the following link.

Abdominal ultrasound was reported unaltered.

After his birth, he was sent to the clinic 46 of the Mexican Social Security Institute of Gomez Palacio, Durango, Mexico, for its handling and neonatology pediatric surgery.

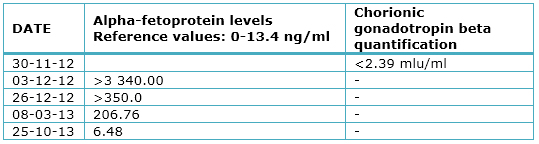

In pediatric surgery is scheduled for resection of tumor, previous indication of tumor markers analysis. These markers report quantification of gonadotropin chorionic human β: 2.39 mIU / ml within normal parameters; alpha-fetoprotein: 3,340 ng / ml (reference: 0 to 13.4) and normal preoperative tests. Surgery is performed seven days after birth.

Dissection by planes is performed following tumor planes with nutritious vessels ligation and hemostasis with cautery, rectum is located prior catheter with Hegar 7 Fr. Adhered rectal tumor but not invasive is dissected and coccyx is resected, tying median sacral artery, besides resecting one small percentage of the tumor at presacal level. Drain suction is placed and it is closed by layers (Figure 3 A and B).

Figure 3 A and B. Posterior view of the newborn after surgery

Findings

A 18x14x10 cm encapsulated tumor was found Altman I. Approximately 80% of its composition is of citrine cystic type and 20% solid. A 100% noninvasive, resection of the tumor that was attached to the rectum was performed, with a minimal percentage of presacral portion; coccyx was also resected.

Pathology report

Macroscopic description: irregularly ovoid specimen is received measuring 16 cm in diameter. The surface shows areas coated by a brown clear and smooth epidermis and bloody appearance areas. When cutting is soft. A unilocular cystic lesion is observed. The walls have a maximum thickness of 0.2 cm. Internal face is smooth light brown, shiny, with reticular appearance areas. A mamelon is seen in one of the poles measuring 4x2.8 cm the area is light brown with congested areas. When cutting is soft with hard areas. The surface is light with chondroid appearance areas.

Microscopic description: malignancy of germinal origin is identified. The cyst wall consists of dense connective tissue coated in the inside by simple squamous epithelium, with no evident alterations. Underlying skin without histological alterations observed. In one pole, a mamelon can be observed in which remnants of glial and choroid tissue, skin, epithelium of respiratory aspect, cartilage, and congestive vessels are identified. From a central point, bone with very little presence of bone marrow is presented. All components are mature and no malignancy data is observed. No percentage of neuroepithelium is presented.

During patient follow-up, alpha-fetoprotein levels decreased to normal values until now. (Table 1)

Table 1. Evolution of alpha-fetoprotein levels.

Discussion

This case is presented because of its low incidence and its rarity. About 3,000 births occur annually at the clinic number 46 of the Mexican Social Security Institute in Gomez Palacio, Durango. We expect to find a case of this nature every 13 to 15 years.

Sacrococcygeal teratomas are extragonadal neoplasms arising in the presacral area. They have an incidence of one per 40,000 live births, and a prevalence of one in 21,000 births. Although sacrococcygeal teratoma is a rare tumor, it is the most common malignancy of germ cells in newborns and children under two years. Its presentation may be forming large cysts or as solid mass. They are usually located in the midline of the body. In general, the order of frequency regarding to its location is as follows: sacrococcygeal, gonadal, retroperitoneal, cervical, mediastinal, oropharyngeal and other (gastric, hepatic, intracranial). It predominates in females, but in males malignancy is more recurrent [6],[7],[8].

The term "teratoma," derives from the Greek word "teraton" meaning monster. In 1869 Virchow applied this term to a tumor originating in the sacrococcygeal region [9].

Teratomas are formed by multiple foreign tissues to the organ or place where they are produced. Most lesions occur in the neonatal period and may be benign or malignant, cystic or solid. Although teratomas are sometimes defined by having the three embryonic layers (endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm), recent classifications include the monodermal type [8].

Sacrococcygeal teratoma can grow to huge dimensions, causing complications related to mass effect such as distortion of the anatomy of the pelvis and sacrum, bladder obstruction and dystocia [6],[10].

The Section on surgery of The American Academy of Pediatrics proposed a useful clinical postnatal classification system, that describes four types of sacrococcygeal teratoma according to their location [11]:

- Type I: predominantly external, with minimum presacral component. It is the most common and the least malignant (45.8%).

- Type II: External with significant intrapelvic component

- Type III: External with pelvic mass. In this one, it predominates an extension through the abdomen.

- Type IV: It is presacral without external presentation or significant pelvic extension. It is the most malignant.

As for their tissue composition, there are three histological main types [12],[13]:

- Mature: well differentiated tissues such as brain, skin and bones.

- Immature: neuroplia, neural tube-like structures in addition to mature components. They have high incidence of malignancy. There are four categories depending on the amount of immature tissue present and the mitotic activity degree.

- Teratoma with malignant components: this teratoma contains one or more malignant germ cell tumors. For example choriocarcinoma, germinoma, embryonal carcinoma, endodermal sinus tumor; in addition to mature or immature tissue.

Two major problems remain to be solved: longterm functional sequelae (fecal and urological) in addition to recurrence [14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19]. Tuladhar et al. [20] mentioned in a review in 2000, that in most publications recurrence rate of sacrococcygeal teratomas varies between 7.5 and 22% of patients. On the other hand, in a series of 20 cases published in Mexico in 2003 by Gutiérrez Ureña et al. [4], postsurgical evolution was satisfactory and cases remained free of disease during 36 months follow up. Some possible causal factors for recurrence include incomplete resection with microscopic residues, non all coccyx resection and tumor spread.

Diagnosis as a large mass protruding from the sacral /buttock is often performed in utero by ultrasound. Other findings include erosion of a vertebral body or soft tissue mass with areas of calcification in radiography [21],[22].

It is important to identify whether the lesions are cystic or not, since cystic lesions have a better prognosis than solid ones, women also have a better prognosis than men. Lesions diagnosed at two months of age, are more likely to contain malignant tissue. Sacrococcygeal teratomas tend to metastasize to the liver, lungs and lymph nodes. Recurrence has been found after 40 years of resection, which may be announced by alpha-fetoprotein levels. Not only is ultrasound useful for the diagnosis, but it also can be used to monitor tumor progression, detect complications and establish management [21].

Although the majority of the cases are benign, sacrococcygeal teratomas are linked to high morbidity and mortality from preterm deliveries, along with complications such as malignant invasion, tumor hemorrhage, obstruction of umbilical flow and high output heart failure, [23]. Death happens primarily in fetuses with solid and highly vascularized fast growing teratomas that can lead to high output cardiac insufficiency. This happens because the tumor acts as a large arteriovenous malformation [24]. Because some of these complications can be prenatally detected and treated appropriately, the prenatal diagnosis of sacrococcygeal teratomas is very important [25],[26].

The main treatment for sacrococcygeal teratoma, regardless of histological type, is complete resection of the tumor and the coccyx [27]. If this procedure is not performed, the risk of recurrence is extremely high. In patients with mature sacrococcygeal teratoma, the only recommended treatment is surgery. In immature sacrococcygeal teratoma, the treatment includes surgery (removal of the sacrum and coccyx), followed by observation. Sometimes a mature or immature teratoma also contains malignant cells. The teratoma and malignant cells may need to be treated differently. Regular follow-up examinations are performed by imaging procedures and tumor marker tests of alpha-fetoprotein [27].

The sacrococcygeal teratoma has a relapse rate of about 4% (39 months follow- up) after resection and a minimum three-year follow-up is set [20],[22]. There is little evidence to provide guidance on follow-up care for children with sacrococcygeal teratomas. The following tests and procedures may be performed at the physician discretion, when tumor markers are elevated at diagnosis moment: alpha-fetoprotein and human chorionic gonadotropin β. Both markers should be monitored monthly during six months (period of highest risk), and then every three months until completing three years as recommended by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health in the United States [15],[27].

Tumor markers

Yolk sac tumors produce alpha-fetoprotein, while germinomas (seminomas and dysgerminomas) and especially choriocarcinomas produce human chorionic gonadotropin β, resulting in elevated serum levels of these substances. Most children with malignant sacrococcygeal teratomas will have a component of yolk sac tumor, along with elevations in concentrations of alpha-fetoprotein, which are monitored in series during treatment to help assess their response. Benign teratomas and immature teratomas may produce small elevations of alpha-fetoprotein and human chorionic gonadotropin β [28],[29],[30],[31].

Conclusions

We can claim that sacrococcygeal teratomas are rare tumors in Mexico. They originate as a remnant of the primitive streak and may present with any histological type of the three germ layers. In the majority of the cases they are benign tumors; the risk of recurrence or malignant transformation is low. It is important to recognize the existence of this pathology in order to have the clinical expertise that offers timely diagnosis, an appropriate and multidisciplinary treatment. Monitoring with alpha-fetoprotein and ultrasound is a key to detect recurrence or postoperative complications.

Finally, reviewing the literature and researching these isolated cases that present at the second level of care, is probably the best tool to keep health professionals up to date and help them provide better care to their patients.

Notes

Readers can request more images by directly contacting the author responsible for the publication.

From the editor

This article was originally submitted in Spanish and was translated into English by the authors. The Journal has not copyedited this version.

Ethical issues

The Journal certifies that this study has been approved by the Local Committee for Research and Ethics in Health Research at the Mexican Social Security Institute. This committee refers that ethical aspects about information management and procedures were respected and it has evidence of the patient's consent to publish his case.

Conflicts of interest statement.

The authors have completed the conflict of interests declaration form from the ICMJE, which has been translated into Spanish by Medwave, and they declare that they have not received any funding whatsoever to write this article, nor have they any conflict of interests with the matter dealt herein. Forms can be requested to the responsible author or the editorial direction of the Journal.

Figure 1. Anterior view of the newborn, with the presence of a mass in the sacral region with dimensions: 16.5x8.5x12 cm before surgery.

Figure 1. Anterior view of the newborn, with the presence of a mass in the sacral region with dimensions: 16.5x8.5x12 cm before surgery.

Figure 2 A and B. Contrast enhanced computerized axial tomography scan

Figure 2 A and B. Contrast enhanced computerized axial tomography scan

Figure 3 A and B. Posterior view of the newborn after surgery

Figure 3 A and B. Posterior view of the newborn after surgery

Table 1. Evolution of alpha-fetoprotein levels.

Table 1. Evolution of alpha-fetoprotein levels.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Se presenta el caso de un recién nacido del género masculino que es enviado a la clínica 46 del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social de Gómez Palacio, Durango, México para manejo por cirugía pediátrica y neonatología, por la presencia de una masa en región sacrococígea que fue detectada en la semana 24 de gestación como probable mielomeningocele. A las 32 semanas de gestación se observó un mayor crecimiento y se sospechó de un higroma quístico. Se programa cesárea a las 38 semanas de gestación y, después de exámenes imagenológicos, se realiza resección del tumor sin complicaciones. El estudio anatomopatológico confirmó el diagnóstico de teratoma sacrococcígeo. La evolución posoperatoria inmediata y su condición en la actualidad, son satisfactorias.

Authors:

Ricardo Molina Vital[1], José Martín de Santiago Valenzuela[2], Roberto Carlos de Lira Barraza[2]

Authors:

Ricardo Molina Vital[1], José Martín de Santiago Valenzuela[2], Roberto Carlos de Lira Barraza[2]

E-mail: rickymol@hotmail.com

Citation: Molina Vital 2, de Santiago Valenzuela JM, de Lira Barraza RC. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: case report. Medwave 2015 May;15(4):e6137 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2015.04.6137

Submission date: 9/1/2015

Acceptance date: 3/5/2015

Publication date: 12/5/2015

Origin: not requested

Type of review: reviewed by three external peer reviewers, double-blind

Comments (0)

We are pleased to have your comment on one of our articles. Your comment will be published as soon as it is posted. However, Medwave reserves the right to remove it later if the editors consider your comment to be: offensive in some sense, irrelevant, trivial, contains grammatical mistakes, contains political harangues, appears to be advertising, contains data from a particular person or suggests the need for changes in practice in terms of diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic interventions, if that evidence has not previously been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No comments on this article.

To comment please log in

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics.

Medwave provides HTML and PDF download counts as well as other harvested interaction metrics. There may be a 48-hour delay for most recent metrics to be posted.

- Gabra HO, Jesudason EC, McDowell HP, Pizer BL, Losty PD. Sacrococcygeal teratoma--a 25-year experience in a UK regional center. J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Sep;41(9):1513-6. | PubMed |

- Berbel Tornero O, Ferrís i Tortajada J, Ortega García JA. [Neonatal neoplasms: a single-centre experience]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2007 Jul;67(1):85-6. | PubMed | Link |

- Hase T, Kodama M, Kishida A, Shimadera S, Aotani H, Shimada M, et al. Techniques available for the management of massive sacrococcygeal teratomas. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001 Mar;17(2-3):232-4. | PubMed |

- Gutiérrez Ureña JA, Calderón Elvir CA, Ruano Aguilar J, Vásquez Gutiérrez E, Duarte Valencia JC, Barraza León. Teratoma sacrococcígeo: informe de veinte casos. Act Med Grupo Angeles. 2003;1(2):82-86. | Link |

- Bruno Catoia F, Ricardo Ibañez G, Marco Valenzuela A. Teratoma sacrococcígeo: reporte de un caso, desde el diagnóstico antenatal a la resección y reconstrucción primaria. Revista Anacem. 2013;VII(2013):27-31. | Link |

- Isaacs H Jr. Perinatal (fetal and neonatal) germ cell tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2004 Jul;39(7):1003-13. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Gucciardo L, Uyttebroek A, De Wever I, Renard M, Claus F, Devlieger R, et al. Prenatal assessment and management of sacrococcygeal teratoma. Prenat Diagn. 2011 Jul;31(7):678-88. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Victoria Miñana I, Ruiz Company S. Teratomas en la Infancia. Arch Dom Pediatr. 1984 Ene-abr;20(1):15-22. | Link |

- Virchow R. Über die sakralgeschwulst des schliewener kindes. Klin Wochenschr. 1869;46:132.

- Bianchi DW, Crombleholme TM, D'Alton ME. Fetology: diagnosis and management of the fetal patient. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division; 2010: xix.

- Altman RP, Randolph JG, Lilly JR. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: American Academy of Pediatrics Surgical Section Survey-1973. J Pediatr Surg. 1974 Jun;9(3):389-98. | PubMed |

- Quevedo R. Tumores de células germinales. Rev Peruana Radiol. 1999;3(7). | Link |

- enachi A, Durin L, Vasseur Maurer S, Aubry MC, Parat S, Herlicoviez M, et al. Prenatally diagnosed sacrococcygeal teratoma: a prognostic classification. J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Sep;41(9):1517-21. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Havránek P, Rubenson A, Güth D, Frenckner B, Olsen L, Kornfält SA. et al. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in Sweden: a 10-year national retrospective study. J Pediatr Surg. 1992 Nov;27(11):1447-50. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Rescorla FJ, Sawin RS, Coran AG, Dillon PW, Azizkhan RG. Long-term outcome for infants and children with sacrococcygeal teratoma: a report from the Childrens Cancer Group. J Pediatr Surg. 1998 Feb;33(2):171-6. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Malone PS, Spitz L, Kiely EM, Brereton RJ, Duffy PG, Ransley PG. The functional sequelae of sacrococcygeal teratoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1990 Jun;25(6):679-80. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Rintala R, Lahdenne P, Lindahl H, Siimes M, Heikinheimo M. Anorectal function in adults operated for a benign sacrococcygeal teratoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1993 Sep;28(9):1165-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Lahdenne P, Wikström S, Heikinheimo M, Marttinen E, Siimes MA. Late urologic sequelae after surgery for congenital sacrococcygeal teratoma. Pediatr Surg Int. 1992;7(3):195- 8. | CrossRef |

- Schropp KP, Lobe TE, Rao B, Mutabagani K, Kay GA, Gilchrist BF, et al. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: the experience of four decades. J Pediatr Surg. 1992 Aug;27(8):1075-8; discussion 1078-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Tuladhar R, Patole SK, Whitehall JS. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in the perinatal period. Postgrad Med J. 2000 Dec;76(902):754-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Shah RU, Lawrence C, Fickenscher KA, Shao L, Lowe LH. Imaging of pediatric pelvic neoplasms. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011 Jul;49(4):729-48, vi. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Grigore M, Iliev G. Diagnosis of sacrococcygeal teratoma using two and three-dimensional ultrasonography: two cases reported and a literature review. Med Ultrason. 2014 Sep;16(3):274-7. | PubMed | Link |

- Holterman AX, Filiatrault D, Lallier M, Youssef S. The natural history of sacrococcygeal teratomas diagnosed through routine obstetric sonogram: a single institution experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1998 Jun;33(6):899-903. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Langer JC, Harrison MR, Schmidt KG, Silverman NH, Anderson RL, Goldberg JD, et al. Fetal hydrops and death from sacrococcygeal teratoma: rationale for fetal surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989 May;160(5 Pt 1):1145-50. | CrossRef | PubMed |

- Huddart SN, Mann JR, Robinson K, Raafat F, Imeson J, Gornall P, et al. Sacrococcygeal teratomas: the UK Children's Cancer Study Group's experience. I. Neonatal. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003 Apr;19(1-2):47-51. | PubMed |

- Albin A, Isaacs H Jr. Germ cell tumor. In: Pizzo PA. Poplack DG, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1993:867-887.

- Instituto Nacional de Cáncer. De los Institutos Nacionales de Salud de los EE. UU. Tumores extracraneales de células germinativas en la niñez: Tratamiento (PDQ®). cancer.gov [on line]. | Link |

- Marina N, Fontanesi J, Kun L, Rao B, Jenkins JJ, Thompson EI, et al. Treatment of childhood germ cell tumors. Review of the St. Jude experience from 1979 to 1988. Cancer. 1992 Nov 15;70(10):2568-75. | PubMed |

- Wu JT, Book L, Sudar K. Serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) levels in normal infants. Pediatr Res. 1981 Jan;15(1):50-2. | PubMed |

- Marina NM, Cushing B, Giller R, Cohen L, Lauer SJ, Ablin A, et al. Complete surgical excision is effective treatment for children with immature teratomas with or without malignant elements: A Pediatric Oncology Group/Children's Cancer Group Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Jul;17(7):2137-43. | PubMed |

- Göbel U, Calaminus G, Schneider DT, Koch S, Teske C, Harms D. The malignant potential of teratomas in infancy and childhood: the MAKEI experiences in non-testicular teratoma and implications for a new protocol. Klin Padiatr. 2006 Nov-Dec;218(6):309-14. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gabra HO, Jesudason EC, McDowell HP, Pizer BL, Losty PD. Sacrococcygeal teratoma--a 25-year experience in a UK regional center. J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Sep;41(9):1513-6. | PubMed |

Gabra HO, Jesudason EC, McDowell HP, Pizer BL, Losty PD. Sacrococcygeal teratoma--a 25-year experience in a UK regional center. J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Sep;41(9):1513-6. | PubMed | Berbel Tornero O, Ferrís i Tortajada J, Ortega García JA. [Neonatal neoplasms: a single-centre experience]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2007 Jul;67(1):85-6. | PubMed | Link |

Berbel Tornero O, Ferrís i Tortajada J, Ortega García JA. [Neonatal neoplasms: a single-centre experience]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2007 Jul;67(1):85-6. | PubMed | Link | Hase T, Kodama M, Kishida A, Shimadera S, Aotani H, Shimada M, et al. Techniques available for the management of massive sacrococcygeal teratomas. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001 Mar;17(2-3):232-4. | PubMed |

Hase T, Kodama M, Kishida A, Shimadera S, Aotani H, Shimada M, et al. Techniques available for the management of massive sacrococcygeal teratomas. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001 Mar;17(2-3):232-4. | PubMed | Gutiérrez Ureña JA, Calderón Elvir CA, Ruano Aguilar J, Vásquez Gutiérrez E, Duarte Valencia JC, Barraza León. Teratoma sacrococcígeo: informe de veinte casos. Act Med Grupo Angeles. 2003;1(2):82-86. | Link |

Gutiérrez Ureña JA, Calderón Elvir CA, Ruano Aguilar J, Vásquez Gutiérrez E, Duarte Valencia JC, Barraza León. Teratoma sacrococcígeo: informe de veinte casos. Act Med Grupo Angeles. 2003;1(2):82-86. | Link | Bruno Catoia F, Ricardo Ibañez G, Marco Valenzuela A. Teratoma sacrococcígeo: reporte de un caso, desde el diagnóstico antenatal a la resección y reconstrucción primaria. Revista Anacem. 2013;VII(2013):27-31. | Link |

Bruno Catoia F, Ricardo Ibañez G, Marco Valenzuela A. Teratoma sacrococcígeo: reporte de un caso, desde el diagnóstico antenatal a la resección y reconstrucción primaria. Revista Anacem. 2013;VII(2013):27-31. | Link | Isaacs H Jr. Perinatal (fetal and neonatal) germ cell tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2004 Jul;39(7):1003-13. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Isaacs H Jr. Perinatal (fetal and neonatal) germ cell tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2004 Jul;39(7):1003-13. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gucciardo L, Uyttebroek A, De Wever I, Renard M, Claus F, Devlieger R, et al. Prenatal assessment and management of sacrococcygeal teratoma. Prenat Diagn. 2011 Jul;31(7):678-88. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gucciardo L, Uyttebroek A, De Wever I, Renard M, Claus F, Devlieger R, et al. Prenatal assessment and management of sacrococcygeal teratoma. Prenat Diagn. 2011 Jul;31(7):678-88. | CrossRef | PubMed | Victoria Miñana I, Ruiz Company S. Teratomas en la Infancia. Arch Dom Pediatr. 1984 Ene-abr;20(1):15-22. | Link |

Victoria Miñana I, Ruiz Company S. Teratomas en la Infancia. Arch Dom Pediatr. 1984 Ene-abr;20(1):15-22. | Link | Virchow R. Über die sakralgeschwulst des schliewener kindes. Klin Wochenschr. 1869;46:132.

Virchow R. Über die sakralgeschwulst des schliewener kindes. Klin Wochenschr. 1869;46:132.  Bianchi DW, Crombleholme TM, D'Alton ME. Fetology: diagnosis and management of the fetal patient. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division; 2010: xix.

Bianchi DW, Crombleholme TM, D'Alton ME. Fetology: diagnosis and management of the fetal patient. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division; 2010: xix.  Altman RP, Randolph JG, Lilly JR. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: American Academy of Pediatrics Surgical Section Survey-1973. J Pediatr Surg. 1974 Jun;9(3):389-98. | PubMed |

Altman RP, Randolph JG, Lilly JR. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: American Academy of Pediatrics Surgical Section Survey-1973. J Pediatr Surg. 1974 Jun;9(3):389-98. | PubMed | enachi A, Durin L, Vasseur Maurer S, Aubry MC, Parat S, Herlicoviez M, et al. Prenatally diagnosed sacrococcygeal teratoma: a prognostic classification. J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Sep;41(9):1517-21.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

enachi A, Durin L, Vasseur Maurer S, Aubry MC, Parat S, Herlicoviez M, et al. Prenatally diagnosed sacrococcygeal teratoma: a prognostic classification. J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Sep;41(9):1517-21.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Havránek P, Rubenson A, Güth D, Frenckner B, Olsen L, Kornfält SA. et al. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in Sweden: a 10-year national retrospective study. J Pediatr Surg. 1992 Nov;27(11):1447-50.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Havránek P, Rubenson A, Güth D, Frenckner B, Olsen L, Kornfält SA. et al. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in Sweden: a 10-year national retrospective study. J Pediatr Surg. 1992 Nov;27(11):1447-50.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Rescorla FJ, Sawin RS, Coran AG, Dillon PW, Azizkhan RG. Long-term outcome for infants and children with sacrococcygeal teratoma: a report from the Childrens Cancer Group. J Pediatr Surg. 1998 Feb;33(2):171-6. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Rescorla FJ, Sawin RS, Coran AG, Dillon PW, Azizkhan RG. Long-term outcome for infants and children with sacrococcygeal teratoma: a report from the Childrens Cancer Group. J Pediatr Surg. 1998 Feb;33(2):171-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | Malone PS, Spitz L, Kiely EM, Brereton RJ, Duffy PG, Ransley PG. The functional sequelae of sacrococcygeal teratoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1990 Jun;25(6):679-80. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Malone PS, Spitz L, Kiely EM, Brereton RJ, Duffy PG, Ransley PG. The functional sequelae of sacrococcygeal teratoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1990 Jun;25(6):679-80. | CrossRef | PubMed | Rintala R, Lahdenne P, Lindahl H, Siimes M, Heikinheimo M. Anorectal function in adults operated for a benign sacrococcygeal teratoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1993 Sep;28(9):1165-7.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Rintala R, Lahdenne P, Lindahl H, Siimes M, Heikinheimo M. Anorectal function in adults operated for a benign sacrococcygeal teratoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1993 Sep;28(9):1165-7.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Lahdenne P, Wikström S, Heikinheimo M, Marttinen E, Siimes MA. Late urologic sequelae after surgery for congenital sacrococcygeal teratoma. Pediatr Surg Int. 1992;7(3):195- 8.

| CrossRef |

Lahdenne P, Wikström S, Heikinheimo M, Marttinen E, Siimes MA. Late urologic sequelae after surgery for congenital sacrococcygeal teratoma. Pediatr Surg Int. 1992;7(3):195- 8.

| CrossRef | Schropp KP, Lobe TE, Rao B, Mutabagani K, Kay GA, Gilchrist BF, et al. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: the experience of four decades. J Pediatr Surg. 1992 Aug;27(8):1075-8; discussion 1078-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Schropp KP, Lobe TE, Rao B, Mutabagani K, Kay GA, Gilchrist BF, et al. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: the experience of four decades. J Pediatr Surg. 1992 Aug;27(8):1075-8; discussion 1078-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Tuladhar R, Patole SK, Whitehall JS. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in the perinatal period. Postgrad Med J. 2000 Dec;76(902):754-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Tuladhar R, Patole SK, Whitehall JS. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in the perinatal period. Postgrad Med J. 2000 Dec;76(902):754-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Shah RU, Lawrence C, Fickenscher KA, Shao L, Lowe LH. Imaging of pediatric pelvic neoplasms. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011 Jul;49(4):729-48, vi. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Shah RU, Lawrence C, Fickenscher KA, Shao L, Lowe LH. Imaging of pediatric pelvic neoplasms. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011 Jul;49(4):729-48, vi. | CrossRef | PubMed | Grigore M, Iliev G. Diagnosis of sacrococcygeal teratoma using two and three-dimensional ultrasonography: two cases reported and a literature review. Med Ultrason. 2014 Sep;16(3):274-7.

| PubMed | Link |

Grigore M, Iliev G. Diagnosis of sacrococcygeal teratoma using two and three-dimensional ultrasonography: two cases reported and a literature review. Med Ultrason. 2014 Sep;16(3):274-7.

| PubMed | Link | Holterman AX, Filiatrault D, Lallier M, Youssef S. The natural history of sacrococcygeal teratomas diagnosed through routine obstetric sonogram: a single institution experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1998 Jun;33(6):899-903.

| CrossRef | PubMed |

Holterman AX, Filiatrault D, Lallier M, Youssef S. The natural history of sacrococcygeal teratomas diagnosed through routine obstetric sonogram: a single institution experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1998 Jun;33(6):899-903.

| CrossRef | PubMed | Langer JC, Harrison MR, Schmidt KG, Silverman NH, Anderson RL, Goldberg JD, et al. Fetal hydrops and death from sacrococcygeal teratoma: rationale for fetal surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989 May;160(5 Pt 1):1145-50. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Langer JC, Harrison MR, Schmidt KG, Silverman NH, Anderson RL, Goldberg JD, et al. Fetal hydrops and death from sacrococcygeal teratoma: rationale for fetal surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989 May;160(5 Pt 1):1145-50. | CrossRef | PubMed | Huddart SN, Mann JR, Robinson K, Raafat F, Imeson J, Gornall P, et al. Sacrococcygeal teratomas: the UK Children's Cancer Study Group's experience. I. Neonatal. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003 Apr;19(1-2):47-51. | PubMed |

Huddart SN, Mann JR, Robinson K, Raafat F, Imeson J, Gornall P, et al. Sacrococcygeal teratomas: the UK Children's Cancer Study Group's experience. I. Neonatal. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003 Apr;19(1-2):47-51. | PubMed | Albin A, Isaacs H Jr. Germ cell tumor. In: Pizzo PA. Poplack DG, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1993:867-887.

Albin A, Isaacs H Jr. Germ cell tumor. In: Pizzo PA. Poplack DG, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1993:867-887.  Instituto Nacional de Cáncer. De los Institutos Nacionales de Salud de los EE. UU. Tumores extracraneales de células germinativas en la niñez: Tratamiento (PDQ®). cancer.gov [on line].

| Link |

Instituto Nacional de Cáncer. De los Institutos Nacionales de Salud de los EE. UU. Tumores extracraneales de células germinativas en la niñez: Tratamiento (PDQ®). cancer.gov [on line].

| Link | Marina N, Fontanesi J, Kun L, Rao B, Jenkins JJ, Thompson EI, et al. Treatment of childhood germ cell tumors. Review of the St. Jude experience from 1979 to 1988. Cancer. 1992 Nov 15;70(10):2568-75. | PubMed |

Marina N, Fontanesi J, Kun L, Rao B, Jenkins JJ, Thompson EI, et al. Treatment of childhood germ cell tumors. Review of the St. Jude experience from 1979 to 1988. Cancer. 1992 Nov 15;70(10):2568-75. | PubMed | Wu JT, Book L, Sudar K. Serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) levels in normal infants. Pediatr Res. 1981 Jan;15(1):50-2. | PubMed |

Wu JT, Book L, Sudar K. Serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) levels in normal infants. Pediatr Res. 1981 Jan;15(1):50-2. | PubMed | Marina NM, Cushing B, Giller R, Cohen L, Lauer SJ, Ablin A, et al. Complete surgical excision is effective treatment for children with immature teratomas with or without malignant elements: A Pediatric Oncology Group/Children's Cancer Group Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Jul;17(7):2137-43. | PubMed |

Marina NM, Cushing B, Giller R, Cohen L, Lauer SJ, Ablin A, et al. Complete surgical excision is effective treatment for children with immature teratomas with or without malignant elements: A Pediatric Oncology Group/Children's Cancer Group Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Jul;17(7):2137-43. | PubMed |Systematization of initiatives in sexual and reproductive health about good practices criteria in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in primary health care in Chile

Clinical, psychological, social, and family characterization of suicidal behavior in Chilean adolescents: a multiple correspondence analysis