Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Para Descargar PDF debe Abrir sesión.

Palabras clave: methadone, morphine, postoperative pain, intravenous anesthesia, aparoscopic cholecystectomy

Background

Postoperative pain management contributes to reducing postoperative morbidity and unscheduled readmission. Compared to other opioids that manage postoperative pain like morphine, few randomized trials have tested the efficacy of intraoperatively administered methadone to provide evidence for its regular use or be included in clinical guidelines.

Methods

We conducted a randomized clinical trial comparing the use of intraoperative methadone to assess its impact on postoperative pain. Eighty-six patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy were allocated to receive either methadone (0.08 mg/kg) or morphine (0.08 mg/kg).

Results

Individuals who received methadone required less rescue morphine in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit for postoperative pain than those who received morphine (p = 0.0078). The patients from the methadone group reported less pain at 5 and 15 minutes and 12 and 24 hours following Post Anesthesia Care Unit discharge, exhibiting fewer episodes of nausea. Time to eye-opening was equivalent between the two groups.

Conclusion

Intraoperative use of methadone resulted in better management of postoperative pain, supporting its use as part of a multimodal pain management strategy for laparoscopic cholecystectomy under remifentanil-based anesthesia.

|

Main messages

|

Postoperative pain management is an essential part of the anesthetic plan to address tissue injury following surgery and reduce postoperative morbidity, improving the perceived quality of care. For uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy, pain is the primary cause of prolonged hospital stay and, in the context of outpatient surgery, is the leading cause of unscheduled readmission[1],[2],[3].

Remifentanil is currently the opioid of choice for intraoperative pain management in laparoscopic surgery as it allows rapid titration resulting in predictable arousal time, independent of dose and duration of infusion[4],[5]. It does not, however, adequately cover postoperative pain and may cause tolerance and hyperalgesia[6],[7],[8],[9]. Although the whole process is not fully elucidated, activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors is proposed as a mechanism[10],[11].

The use of NMDA receptor antagonists during surgery is purported to counter the hyperalgesia associated with the use of opioids[9],[10],[11],[12], and the use of agents such as ketamine at subanesthetic doses have resulted in decreased acute postoperative pain and less rescue opioid consumption[13],[14] included in the context of remifentanil-based anesthesia[15]. The intraoperative use of methadone is an attractive option to cover postoperative pain due to its dual effect as an agonist at opioid receptors and non-competitive antagonist at NMDA receptors[16]. This strategy may reduce the requirement for rescue morphine and its associated adverse effects[12]. Indeed, several research groups report positive and safe results with methadone in this context, including pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies in adults and children[17],[18],[19], randomized trials in major surgeries in adults and children[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25], and remifentanil-based laparoscopic surgery[26]. However, the risk of bias of these studies has not been evaluated formally.

A recent randomized controlled trial evaluated the performance of methadone (0.1 mg/kg) compared to morphine (0.1 mg/kg) in laparoscopic cholecystectomy and found no difference in the quality of recovery evaluated by the Quality of Recovery Questionnaire (QoR-40)[27].

Despite this, few randomized trials have tested the efficacy of intraoperatively administered methadone, compared to other opioids, when managing postoperative pain to provide evidence for its regular use or be included in clinical guidelines. Therefore, we conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing intraoperative methadone (0.08 mg/kg) to morphine (0.08 mg/kg), evaluating its impact on the total dose of rescue morphine used in post-surgical acute care and on postoperative pain.

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hospital Naval Almirante Nef, in Viña del Mar, Chile (PO3/13), and was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01833715).

The study was conducted at the same hospital from March to September 2013. The design is a parallel-group, randomized clinical trial. Individuals aged 18 to 70, admitted for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status score I or II were invited to participate. We excluded patients with the following characteristics: (i) kidney failure (blood creatinine > 2mg/dl), (ii) history of liver failure, (iii) body mass index (BMI) > 35 kg/m2, (iv) chronic opioid use, (v) recorded hypersensitivity to the drugs under trial and (vi) patients converted to open surgery.

Informed consent and demographical data were collected preoperatively by a member of the research team. The outcome assessors were members of the nursing staff, whom the investigators trained on applying the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) pain scale[28],[29],[30] and on data registration. Data recorded during the procedure included the anesthetic dose administered (remifentanil and propofol), arousal time, surgical duration, hypotensive events, and ephedrine requirement. NRS was assessed and recorded at 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU), and 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours on the ward. We recorded the total doses of rescue medication administered (morphine in the PACU, ketorolac on the ward). The following adverse events and treatments were also recorded: nausea, vomiting, itch, urinary retention, respiratory depression, administration of antiemetics (ondansetron 4mg, IV). On discharge, patients were asked to rate their pain management quality on a four-point Likert scale (very unsatisfied to very satisfied).

Patients were randomized with an automatic computerized sequence, with an allocation ratio of 1:1, to receive either methadone or morphine. The sequence was prepared and concealed by the principal investigator. The principal investigator prepared syringes according to the allocated treatment and delivered these to the anesthesiologist in charge of the procedure. Anesthesiologists, surgeons, nursing staff, and patients were unaware of the allocated treatment.

Induction and maintenance anesthesia was based on remifentanil and propofol, titrated to attain a bi-spectral index value between 40 to 60. Following induction, all patients received dexamethasone 8 mg, ketoprofen 100 mg, and metamizole 2 g. A bolus dose of either methadone 0.08 mg/kg or morphine 0.08 mg/kg, calculated using lean body mass, was administered at the start of surgery, and these doses were chosen based on previous studies[20],[22]. We provided postoperative analgesia using a continuous infusion of ketoprofen 100 mg and metamizole 3 mg. After assessing NRS at predefined times, morphine 1 mg was administered for scores ≥ 4 in the PACU (up to 120 minutes), and ketorolac 30 mg in the ward.

Our protocol and trial registry stated our primary outcome as the total amount of rescue morphine used during the first 24 hours postoperatively; however, due to hospital policy, morphine is not administered outside of the PACU, and stay in recovery is typically two hours. We, therefore, refer to the total amount of rescue morphine and highlight that this was provided in the two hours following surgery. The secondary outcome measure was pain, determined using a Numeric Rating Scale at 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes in the PACU and at 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours postoperatively. We expected the average total dose of rescue morphine to be 4 mg in patients that had received 0.08 mg/kg of morphine during surgery. A sample size of 37 patients per group was calculated to detect at least a 25% pain reduction in the intervention group, anticipating a standard deviation (SD) of 1.5 mg in total morphine rescue dose, with a 0.05% significance level and 80% power. We randomized 86 patients anticipating 15% for possible losses (e.g., withdrawals or conversion to open surgery).

Secondary outcome variables were i) postoperative pain score in the PACU or the ward, at specified time points (resting), ii) total number of ketorolac doses in the ward per patient, iii) arousal time, iv) adverse events and treatment, v) qualification of the quality of analgesia provided by patients at discharge.

Continuous data are presented in means and standard deviations. Categorical data are presented in absolute and relative frequencies. Means ± standard deviations were compared using Student’s t-test. The number of patients (%) was compared using Fisher’s exact test, considering p ≤ 0.05 as significant. All analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp).

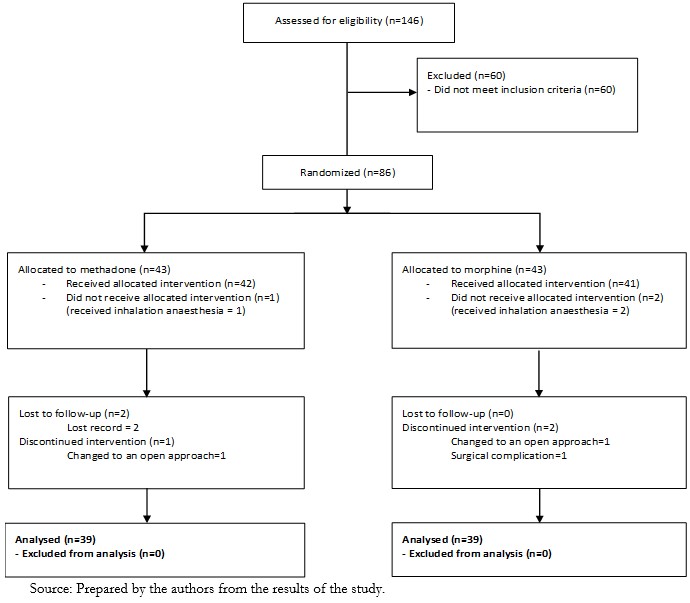

One hundred and forty-six patients were assessed for eligibility, and 60 did not meet the inclusion criteria, the primary reasons being older than 70 years, a body mass index greater than 35, and a few individuals with serum creatinine over 2.0 mg/dl. A total of 86 patients were submitted to the randomization procedure, 43 allocated to the intervention group (methadone), and 43 were allocated to the control group (morphine). Three patients did not receive the intervention and instead received inhalation anesthesia (1 in the methadone group and 2 in the morphine group). Three participants in the methadone group and two in the morphine group were excluded due to a lost record, change to an open approach, or surgical complications (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

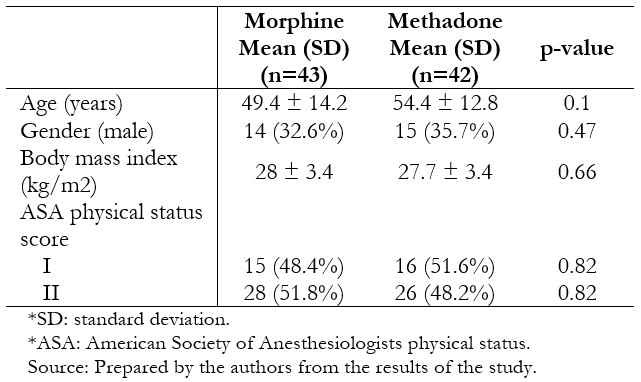

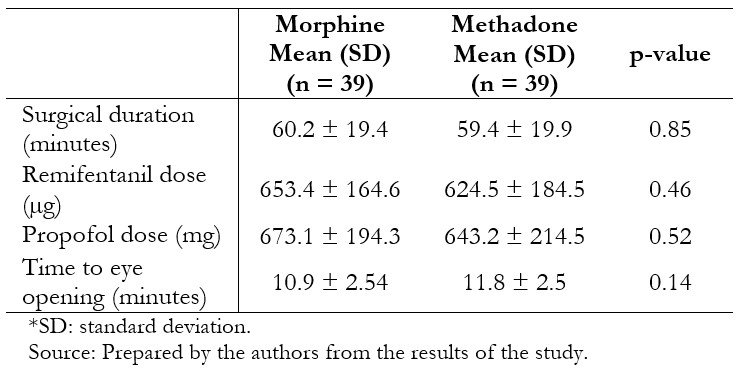

Thirty-nine patients per group were included in the per protocol analysis. The groups were similar in terms of age, body mass index, gender, and physical status (Table 1). Surgical characteristics were likewise similar between the groups (Table 2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of randomized patients.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients who received the intervention.

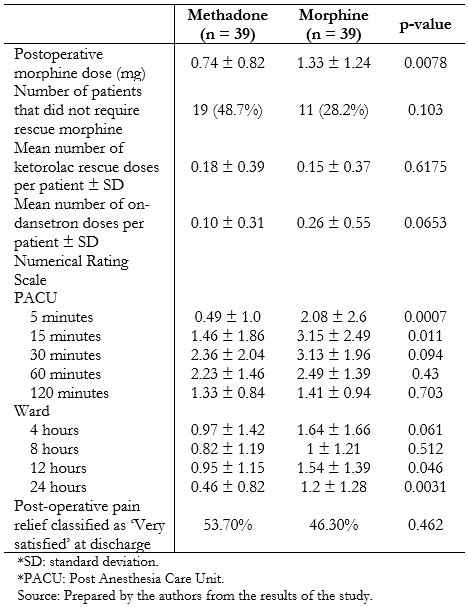

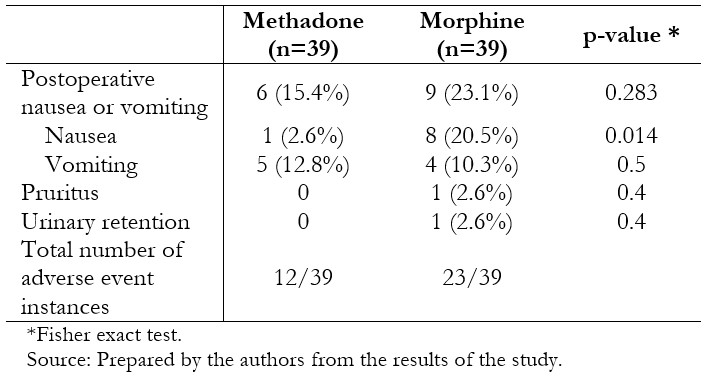

Post-operative analgesia and pain scores are presented in Table 3. Individuals who had received methadone required less rescue morphine postoperatively (0.74 mg ± 0.82 mg versus 1.33 mg ± 1.24 mg, p = 0.0078), without significant differences in the amount of rescue ketorolac in the next 22 hours (0.18 ± 0.39 vs. 0.15 ± 0.37, p = 0.6175). Time to eye-opening was equivalent between the two groups. Pain scores were generally low and differed between groups at 5 and 15 minutes after recovery, and 12 and 24 hours on the ward, being lower in the methadone-treated patients in these scenarios. Fewer patients in the methadone group experienced nausea (2.6% versus 20.5%, p = 0.014), although nausea and vomiting globally were similar between the groups (Table 4).

Table 3. Postoperative analgesia and pain scores.

Table 4. Adverse events in the postoperative period (24hours).

We found patients receiving 0.8 mg/kg of methadone intraoperatively required less morphine rescue for postoperative pain in the first two hours following laparoscopic cholecystectomy than those that had received 0.8 mg/kg of morphine. These patients reported less pain at 5 and 15 minutes, and 12 and 24 hours following PACU discharge, and exhibited fewer episodes of nausea. The use of methadone did not prolong the time to eye-opening.

Our results are similar to a recently published randomized trial from Moro et al., in which the same agents were compared in the context of laparoscopic cholecystectomy[27]. The primary outcome, quality of recovery at 24 hours, evaluated by the QoR-40 questionnaire, was similar between methadone and morphine treated patients. Moro et al. discussed several aspects of their finding, including high overall scores compared to previous work in more complex surgeries and multimodal approach to analgesia. We asked satisfaction with pain management at discharge and found no difference between the groups. Pain, assessed by NRS every 15 minutes while in PACU, was found not to differ between methadone and morphine treated patients; however, the authors report results as pain at rest at an unspecified time point and at 1 hour[27]. Like our work, postoperative opioid analgesia in the PACU was significantly different between methadone and morphine, though Moro and colleagues used dosage as mL (1 mg/kg in 10 mL), continuing with the treatment allocation for a given patient. While the postoperative analgesia approach was different, as all patients in our work received 1 mg of morphine per dose, the findings likely represent quite similar pain requirements as the indication for administering similar doses (maintaining NRS below 3 in Moro et al., and below 4 in our work) despite the lower doses used intraoperatively in our work (0.08 mg/kg of methadone and morphine, compared to 0.1 mg/kg). We likewise found nausea and vomiting events similar between the groups; however, we found a greater occurrence among the morphine-treated individuals when we looked explicitly at nausea. Finally, Moro and colleagues report more morphine-treated individuals with Ramsey sedation scores > 4, a relevant outcome that we did not assess.

One explanation for the difference between methadone and morphine is a less favorable pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profile of morphine that leads to delayed effects relative to plasma concentrations. A greater requirement of rescue narcotics highlights the delayed onset of action of morphine in individuals who received morphine late or at the end of surgery compared to those who received morphine 40 minutes before the end of the procedure, in the context of remifentanil-based anesthesia[31]. In an investigation evaluating plasma levels and maximum effect of several opioids (pupillary diameter), methadone exhibited a more evident association than morphine, where a delay of up to two hours between peak plasma level and maximum effect was observed[16]. Another possibility is the pharmacodynamic property of methadone as both an agonist at opioid receptors and a non-competitive antagonist at NMDA receptors. NMDA receptor antagonists improve the efficacy of opioids, delaying tolerance and decreasing hyperalgesia[32]. Most of the studies comparing morphine and methadone aimed to manage chronic pain in oral and subcutaneous formulations, with proportions of 5-7:1 and 2-14:1, respectively[33],[34]. However, for the management of postoperative pain in abdominal surgeries, using a single intravenous dose, some studies have used a 1:1 ratio[20],[21],[22].

Gourlay and colleagues introduced the use of intraoperative methadone[17],[18],[20],[25],[26],[27], and many research groups have evidenced its adequate efficacy and safety in a variety of surgical contexts[19],[21],[22],[23],[24]. An IV bolus of 20 mg of methadone did not impair hemodynamic stability in patients undergoing major surgery[35]. Another advantage of methadone is that active metabolites are not produced, an issue to be considered when using morphine, especially in patients with kidney failure[36],[37],[38].

One of the limitations of the present trial is that the administration of rescue morphine was given by nursing staff rather than by patients themselves; patient-controlled analgesia likely being a more accurate representation of requirement. We appreciate that the statistically significant difference we report in terms of rescue morphine dose and reduced postoperative pain in the methadone-treated patients may represent a moderate clinical gain. This is likely due to the lower nociceptive burden in laparoscopic surgery and a multimodal approach to pain management in both groups. Methadone may represent a greater gain in surgeries associated with more intense postoperative pain[24],[25]. Future trials to evaluate the efficacy of methadone in surgeries with prolonged remifentanil exposure are desirable, and it would be advisable to incorporate standardized somatosensory tests to evaluate postoperative hyperalgesia[39],[40].

As a subjective variable, pain is most widely assessed through the NRS[41]. It is desirable that studies assessing pain, such as ours, use this scale to enable comparisons across studies facilitating future evidence synthesis efforts, such as inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Our results suggest advantages of intraoperative methadone compared to morphine to treat postoperative pain in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, resulting in less rescue morphine in the PACU and lower NRS scores specific periods. Further, the methadone-treated patients who exhibited less nausea are an important consideration in choosing an opioid within a multimodal treatment strategy in surgeries such as cholecystectomy.

Roles and contributions

NA: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, research, visualization, project management, review and edition. CP: formal analysis, research, review of the original draft. MK, MM: formal analysis, research, writing original draft, review and editing. FA: conceptualization, validation, research, data collection, review and edition. JS: writing original draft, review and editing. EM: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, drafting preliminary project, review and edition.

Ethical consideration

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hospital Naval Almirante Nef, in Viña del Mar, Chile (PO3/13), and was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01833715).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Anesthesiology Department staff at Hospital Naval Almirante Nef for their collaboration with the clinical trial’s conduction.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclosure.

Funding

This work was supported by the Direction of Research Universidad de Valparaíso under grant CIDI8 Interdisciplinary Centre for Health Studies.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of randomized patients.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of randomized patients.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients who received the intervention.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients who received the intervention.

Table 3. Postoperative analgesia and pain scores.

Table 3. Postoperative analgesia and pain scores.

Table 4. Adverse events in the postoperative period (24hours).

Table 4. Adverse events in the postoperative period (24hours).

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Esta obra de Medwave está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 3.0 Unported. Esta licencia permite el uso, distribución y reproducción del artículo en cualquier medio, siempre y cuando se otorgue el crédito correspondiente al autor del artículo y al medio en que se publica, en este caso, Medwave.

Background

Postoperative pain management contributes to reducing postoperative morbidity and unscheduled readmission. Compared to other opioids that manage postoperative pain like morphine, few randomized trials have tested the efficacy of intraoperatively administered methadone to provide evidence for its regular use or be included in clinical guidelines.

Methods

We conducted a randomized clinical trial comparing the use of intraoperative methadone to assess its impact on postoperative pain. Eighty-six patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy were allocated to receive either methadone (0.08 mg/kg) or morphine (0.08 mg/kg).

Results

Individuals who received methadone required less rescue morphine in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit for postoperative pain than those who received morphine (p = 0.0078). The patients from the methadone group reported less pain at 5 and 15 minutes and 12 and 24 hours following Post Anesthesia Care Unit discharge, exhibiting fewer episodes of nausea. Time to eye-opening was equivalent between the two groups.

Conclusion

Intraoperative use of methadone resulted in better management of postoperative pain, supporting its use as part of a multimodal pain management strategy for laparoscopic cholecystectomy under remifentanil-based anesthesia.

Autores:

Nicolás Arriaza[1,2], Cristian Papuzinski[3,4], Matías Kirmayr[4], Marcelo Matta[4], Fernando Aranda[1], Jana Stojanova[3], Eva Madrid[3,4]

Autores:

Nicolás Arriaza[1,2], Cristian Papuzinski[3,4], Matías Kirmayr[4], Marcelo Matta[4], Fernando Aranda[1], Jana Stojanova[3], Eva Madrid[3,4]

Citación: Arriaza N, Papuzinski C, Kirmayr M, Matta M, Aranda F, Stojanova J, et al. Efficacy of methadone for the management of postoperative pain in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomized clinical trial. Medwave 2021;21(2):e8134 doi: 10.5867/medwave.2021.02.8134

Fecha de envío: 17/10/2020

Fecha de aceptación: 28/1/2021

Fecha de publicación: 23/3/2021

Origen: No solicitado

Tipo de revisión: Con revisión externa por dos pares revisores a doble ciego

Nos complace que usted tenga interés en comentar uno de nuestros artículos. Su comentario será publicado inmediatamente. No obstante, Medwave se reserva el derecho a eliminarlo posteriormente si la dirección editorial considera que su comentario es: ofensivo en algún sentido, irrelevante, trivial, contiene errores de lenguaje, contiene arengas políticas, obedece a fines comerciales, contiene datos de alguna persona en particular, o sugiere cambios en el manejo de pacientes que no hayan sido publicados previamente en alguna revista con revisión por pares.

Aún no hay comentarios en este artículo.

Para comentar debe iniciar sesión

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Medwave publica las vistas HTML y descargas PDF por artículo, junto con otras métricas de redes sociales.

Bisgaard T, Kehlet H, Rosenberg J. Pain and convalescence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Surg. 2001 Feb;167(2):84-96. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bisgaard T, Kehlet H, Rosenberg J. Pain and convalescence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Surg. 2001 Feb;167(2):84-96. | CrossRef | PubMed | Lau H, Brooks DC. Predictive factors for unanticipated admissions after ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 2001 Oct;136(10):1150-3. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Lau H, Brooks DC. Predictive factors for unanticipated admissions after ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 2001 Oct;136(10):1150-3. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bisgaard T. Analgesic treatment after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a critical assessment of the evidence. Anesthesiology. 2006 Apr;104(4):835-46. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bisgaard T. Analgesic treatment after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a critical assessment of the evidence. Anesthesiology. 2006 Apr;104(4):835-46. | CrossRef | PubMed | Egan TD. Remifentanil pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. A preliminary appraisal. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995 Aug;29(2):80-94. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Egan TD. Remifentanil pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. A preliminary appraisal. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995 Aug;29(2):80-94. | CrossRef | PubMed | Michelsen LG, Hug CC Jr. The pharmacokinetics of remifentanil. J Clin Anesth. 1996 Dec;8(8):679-82. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Michelsen LG, Hug CC Jr. The pharmacokinetics of remifentanil. J Clin Anesth. 1996 Dec;8(8):679-82. | CrossRef | PubMed | Guignard B, Bossard AE, Coste C, Sessler DI, Lebrault C, Alfonsi P, et al. Acute opioid tolerance: intraoperative remifentanil increases postoperative pain and morphine requirement. Anesthesiology. 2000 Aug;93(2):409-17. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Guignard B, Bossard AE, Coste C, Sessler DI, Lebrault C, Alfonsi P, et al. Acute opioid tolerance: intraoperative remifentanil increases postoperative pain and morphine requirement. Anesthesiology. 2000 Aug;93(2):409-17. | CrossRef | PubMed | Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2006 Mar;104(3):570-87. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2006 Mar;104(3):570-87. | CrossRef | PubMed | Chang G, Chen L, Mao J. Opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia. Med Clin North Am. 2007 Mar;91(2):199-211. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Chang G, Chen L, Mao J. Opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia. Med Clin North Am. 2007 Mar;91(2):199-211. | CrossRef | PubMed | Koppert W, Schmelz M. The impact of opioid-induced hyperalgesia for postoperative pain. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2007 Mar;21(1):65-83. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Koppert W, Schmelz M. The impact of opioid-induced hyperalgesia for postoperative pain. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2007 Mar;21(1):65-83. | CrossRef | PubMed | Woolf CJ, Thompson SWN. The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain. 1991 Mar;44(3):293-299. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Woolf CJ, Thompson SWN. The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain. 1991 Mar;44(3):293-299. | CrossRef | PubMed | Woolf CJ, Salter MW. Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science. 2000 Jun 9;288(5472):1765-9. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Woolf CJ, Salter MW. Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science. 2000 Jun 9;288(5472):1765-9. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wheeler M, Oderda GM, Ashburn MA, Lipman AG. Adverse events associated with postoperative opioid analgesia: a systematic review. J Pain. 2002 Jun;3(3):159-80. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wheeler M, Oderda GM, Ashburn MA, Lipman AG. Adverse events associated with postoperative opioid analgesia: a systematic review. J Pain. 2002 Jun;3(3):159-80. | CrossRef | PubMed | De Kock M, Lavand'homme P, Waterloos H. 'Balanced analgesia' in the perioperative period: is there a place for ketamine? Pain. 2001 Jun;92(3):373-380. | CrossRef | PubMed |

De Kock M, Lavand'homme P, Waterloos H. 'Balanced analgesia' in the perioperative period: is there a place for ketamine? Pain. 2001 Jun;92(3):373-380. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bell RF, Dahl JB, Moore RA, Kalso E. Perioperative ketamine for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jan 25;(1):CD004603. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bell RF, Dahl JB, Moore RA, Kalso E. Perioperative ketamine for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jan 25;(1):CD004603. | CrossRef | PubMed | Joly V, Richebe P, Guignard B, Fletcher D, Maurette P, Sessler DI, et al. Remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia and its prevention with small-dose ketamine. Anesthesiology. 2005 Jul;103(1):147-55. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Joly V, Richebe P, Guignard B, Fletcher D, Maurette P, Sessler DI, et al. Remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia and its prevention with small-dose ketamine. Anesthesiology. 2005 Jul;103(1):147-55. | CrossRef | PubMed | Kharasch ED. Intraoperative methadone: rediscovery, reappraisal, and reinvigoration? Anesth Analg. 2011 Jan;112(1):13-6. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Kharasch ED. Intraoperative methadone: rediscovery, reappraisal, and reinvigoration? Anesth Analg. 2011 Jan;112(1):13-6. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gourlay GK, Wilson PR, Glynn CJ. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of methadone during the perioperative period. Anesthesiology. 1982 Dec;57(6):458-67. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gourlay GK, Wilson PR, Glynn CJ. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of methadone during the perioperative period. Anesthesiology. 1982 Dec;57(6):458-67. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gourlay GK, Willis RJ, Wilson PR. Postoperative pain control with methadone: influence of supplementary methadone doses and blood concentration--response relationships. Anesthesiology. 1984 Jul;61(1):19-26. | PubMed |

Gourlay GK, Willis RJ, Wilson PR. Postoperative pain control with methadone: influence of supplementary methadone doses and blood concentration--response relationships. Anesthesiology. 1984 Jul;61(1):19-26. | PubMed | Sharma A, Tallchief D, Blood J, Kim T, London A, Kharasch ED. Perioperative pharmacokinetics of methadone in adolescents. Anesthesiology. 2011 Dec;115(6):1153-61. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Sharma A, Tallchief D, Blood J, Kim T, London A, Kharasch ED. Perioperative pharmacokinetics of methadone in adolescents. Anesthesiology. 2011 Dec;115(6):1153-61. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gourlay GK, Willis RJ, Lamberty J. A double-blind comparison of the efficacy of methadone and morphine in postoperative pain control. Anesthesiology. 1986 Mar;64(3):322-7. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gourlay GK, Willis RJ, Lamberty J. A double-blind comparison of the efficacy of methadone and morphine in postoperative pain control. Anesthesiology. 1986 Mar;64(3):322-7. | CrossRef | PubMed | Berde CB, Beyer JE, Bournaki MC, Levin CR, Sethna NF. Comparison of morphine and methadone for prevention of postoperative pain in 3- to 7-year-old children. J Pediatr. 1991 Jul;119(1 Pt 1):136-41. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Berde CB, Beyer JE, Bournaki MC, Levin CR, Sethna NF. Comparison of morphine and methadone for prevention of postoperative pain in 3- to 7-year-old children. J Pediatr. 1991 Jul;119(1 Pt 1):136-41. | CrossRef | PubMed | Chui PT, Gin T. A double-blind randomised trial comparing postoperative analgesia after perioperative loading doses of methadone or morphine. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1992 Feb;20(1):46-51. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Chui PT, Gin T. A double-blind randomised trial comparing postoperative analgesia after perioperative loading doses of methadone or morphine. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1992 Feb;20(1):46-51. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gottschalk A, Durieux ME, Nemergut EC. Intraoperative methadone improves postoperative pain control in patients undergoing complex spine surgery. Anesth Analg. 2011 Jan;112(1):218-23. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gottschalk A, Durieux ME, Nemergut EC. Intraoperative methadone improves postoperative pain control in patients undergoing complex spine surgery. Anesth Analg. 2011 Jan;112(1):218-23. | CrossRef | PubMed | Murphy GS, Szokol JW, Avram MJ, Greenberg SB, Marymont JH, Shear T, et al. Intraoperative Methadone for the Prevention of Postoperative Pain: A Randomized, Double-blinded Clinical Trial in Cardiac Surgical Patients. Anesthesiology. 2015 May;122(5):1112-22. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Murphy GS, Szokol JW, Avram MJ, Greenberg SB, Marymont JH, Shear T, et al. Intraoperative Methadone for the Prevention of Postoperative Pain: A Randomized, Double-blinded Clinical Trial in Cardiac Surgical Patients. Anesthesiology. 2015 May;122(5):1112-22. | CrossRef | PubMed | Murphy GS, Szokol JW, Avram MJ, Greenberg SB, Shear TD, Deshur MA, et al. Clinical Effectiveness and Safety of Intraoperative Methadone in Patients Undergoing Posterior Spinal Fusion Surgery: A Randomized, Double-blinded, Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology. 2017 May;126(5):822-833. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Murphy GS, Szokol JW, Avram MJ, Greenberg SB, Shear TD, Deshur MA, et al. Clinical Effectiveness and Safety of Intraoperative Methadone in Patients Undergoing Posterior Spinal Fusion Surgery: A Randomized, Double-blinded, Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology. 2017 May;126(5):822-833. | CrossRef | PubMed | Simoni RF, Cangiani LM, Pereira AM, Abreu MP, Cangiani LH, Zemi G. Eficácia do emprego da metadona ou da clonidina no intraoperatório para controle da dor pós-operatória imediata após uso de remifentanil [Efficacy of intraoperative methadone and clonidine in pain control in the immediate postoperative period after the use of remifentanil]. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2009 Jul-Aug;59(4):421-30. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Simoni RF, Cangiani LM, Pereira AM, Abreu MP, Cangiani LH, Zemi G. Eficácia do emprego da metadona ou da clonidina no intraoperatório para controle da dor pós-operatória imediata após uso de remifentanil [Efficacy of intraoperative methadone and clonidine in pain control in the immediate postoperative period after the use of remifentanil]. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2009 Jul-Aug;59(4):421-30. | CrossRef | PubMed | Moro ET, Lambert MF, Pereira AL, Artioli T, Graicer G, Bevilacqua J, et al. The effect of methadone on postoperative quality of recovery in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective, randomized, double blinded, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Anesth. 2019 Mar;53:64-69. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Moro ET, Lambert MF, Pereira AL, Artioli T, Graicer G, Bevilacqua J, et al. The effect of methadone on postoperative quality of recovery in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective, randomized, double blinded, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Anesth. 2019 Mar;53:64-69. | CrossRef | PubMed | Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA. Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis. 1978 Aug;37(4):378-81. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA. Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis. 1978 Aug;37(4):378-81. | CrossRef | PubMed | Breivik EK, Björnsson GA, Skovlund E. A comparison of pain rating scales by sampling from clinical trial data. Clin J Pain. 2000 Mar;16(1):22-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Breivik EK, Björnsson GA, Skovlund E. A comparison of pain rating scales by sampling from clinical trial data. Clin J Pain. 2000 Mar;16(1):22-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Serrano-Atero M, Caballero J, Cañas A, García-Saura PL, Serrano-Álvarez C, Prieto J. Valoración del Dolor (I). Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2002;9(2):94-108. [On line]. | Link |

Serrano-Atero M, Caballero J, Cañas A, García-Saura PL, Serrano-Álvarez C, Prieto J. Valoración del Dolor (I). Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2002;9(2):94-108. [On line]. | Link | Muñoz HR, Guerrero ME, Brandes V, Cortínez LI. Effect of timing of morphine administration during remifentanil-based anaesthesia on early recovery from anaesthesia and postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth. 2002 Jun;88(6):814-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Muñoz HR, Guerrero ME, Brandes V, Cortínez LI. Effect of timing of morphine administration during remifentanil-based anaesthesia on early recovery from anaesthesia and postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth. 2002 Jun;88(6):814-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Mao J. NMDA and opioid receptors: their interactions in antinociception, tolerance and neuroplasticity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999 Nov;30(3):289-304. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Mao J. NMDA and opioid receptors: their interactions in antinociception, tolerance and neuroplasticity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999 Nov;30(3):289-304. | CrossRef | PubMed | Gagnon B, Bruera E. Differences in the ratios of morphine to methadone in patients with neuropathic pain versus non-neuropathic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Aug;18(2):120-5. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Gagnon B, Bruera E. Differences in the ratios of morphine to methadone in patients with neuropathic pain versus non-neuropathic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Aug;18(2):120-5. | CrossRef | PubMed | Ripamonti C, Groff L, Brunelli C, Polastri D, Stavrakis A, De Conno F. Switching from morphine to oral methadone in treating cancer pain: what is the equianalgesic dose ratio? J Clin Oncol. 1998 Oct;16(10):3216-21. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Ripamonti C, Groff L, Brunelli C, Polastri D, Stavrakis A, De Conno F. Switching from morphine to oral methadone in treating cancer pain: what is the equianalgesic dose ratio? J Clin Oncol. 1998 Oct;16(10):3216-21. | CrossRef | PubMed | Bowdle TA, Even A, Shen DD, Swardstrom M. Methadone for the induction of anesthesia: plasma histamine concentration, arterial blood pressure, and heart rate. Anesth Analg. 2004 Jun;98(6):1692-7, table of contents. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Bowdle TA, Even A, Shen DD, Swardstrom M. Methadone for the induction of anesthesia: plasma histamine concentration, arterial blood pressure, and heart rate. Anesth Analg. 2004 Jun;98(6):1692-7, table of contents. | CrossRef | PubMed | Christrup LL. Morphine metabolites. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997 Jan;41(1 Pt 2):116-22. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Christrup LL. Morphine metabolites. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997 Jan;41(1 Pt 2):116-22. | CrossRef | PubMed | Smith MT. Neuroexcitatory effects of morphine and hydromorphone: evidence implicating the 3-glucuronide metabolites. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000 Jul;27(7):524-8. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Smith MT. Neuroexcitatory effects of morphine and hydromorphone: evidence implicating the 3-glucuronide metabolites. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000 Jul;27(7):524-8. | CrossRef | PubMed | Vaughan CW, Connor M. In search of a role for the morphine metabolite morphine-3-glucuronide. Anesth Analg. 2003 Aug;97(2):311-2. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Vaughan CW, Connor M. In search of a role for the morphine metabolite morphine-3-glucuronide. Anesth Analg. 2003 Aug;97(2):311-2. | CrossRef | PubMed | Wilder-Smith OH, Tassonyi E, Crul BJ, Arendt-Nielsen L. Quantitative sensory testing and human surgery: effects of analgesic management on postoperative neuroplasticity. Anesthesiology. 2003 May;98(5):1214-22. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Wilder-Smith OH, Tassonyi E, Crul BJ, Arendt-Nielsen L. Quantitative sensory testing and human surgery: effects of analgesic management on postoperative neuroplasticity. Anesthesiology. 2003 May;98(5):1214-22. | CrossRef | PubMed | Rolke R, Baron R, Maier C, Tölle TR, Treede -DR, Beyer A, et al. Quantitative sensory testing in the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS): standardized protocol and reference values. Pain. 2006 Aug;123(3):231-243. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Rolke R, Baron R, Maier C, Tölle TR, Treede -DR, Beyer A, et al. Quantitative sensory testing in the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS): standardized protocol and reference values. Pain. 2006 Aug;123(3):231-243. | CrossRef | PubMed | Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, et al. Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011 Jun;41(6):1073-93. | CrossRef | PubMed |

Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, et al. Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011 Jun;41(6):1073-93. | CrossRef | PubMed |